There are few chapters in American military history as daring, secretive, and defining as MACV-SOG, the Military Assistance Command-Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group. A small band of elite Green Berets who operated deep behind enemy lines, often without acknowledgment, and always with extraordinary courage.

These men were tasked with missions that had never been done before and might never be done again. Their work in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam forged the tactics, technology, and mindset that would become the DNA of modern Special Operations.

But when they came home, many faced a different kind of battle. The Vietnam era brought with it a complex legacy, one of heroism and heartbreak, pride and pain. Some became business and political leaders; others struggled for decades to find peace. Yet through it all, the brotherhood forged in MACV-SOG never wavered.

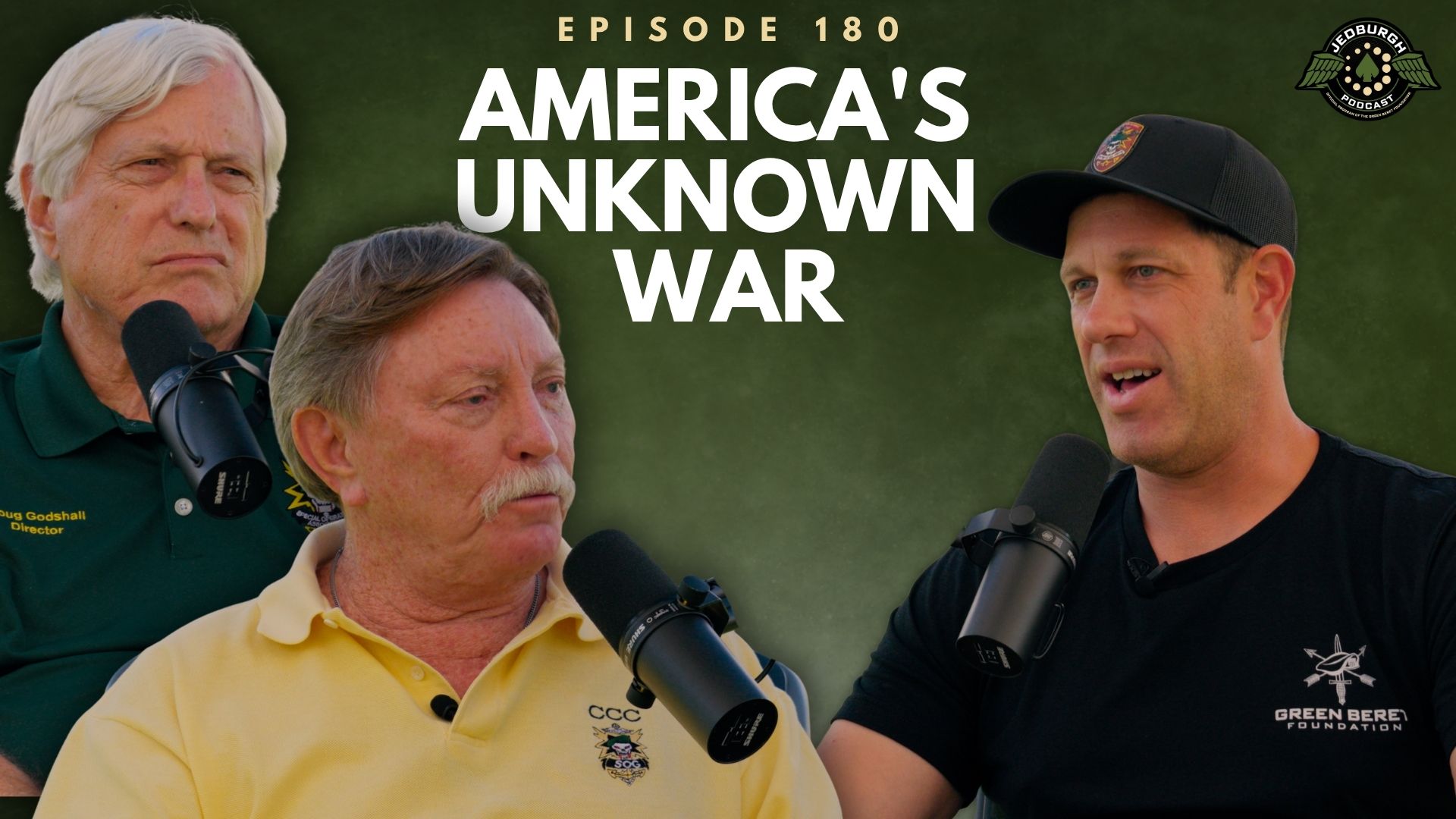

Live from the 2nd Annual Stars and Stripes Classic, we sat down with Doug Godshall and Jim Shorten, two veterans of MACV-SOG, to honor their service, preserve their stories, and remind today’s Green Berets what courage, sacrifice, and innovation truly mean.

This episode is about the origins of Special Forces as we know them today, the unbreakable bonds formed in war, and the duty we all share to ensure that the lessons of MACV-SOG live on in every generation of those who don the Green Beret.

The Jedburgh Podcast is brought to you by University of Health & Performance, providing our Veterans world-class education and training as fitness and nutrition entrepreneurs.

Follow the Jedburgh Podcast and the Green Beret Foundation on social media. Listen on your favorite podcast platform, read on our website, and watch the full video version on YouTube as we show why America must continue to lead from the front, no matter the challenge.

—

—

Doug, Jim, welcome to The Jedburgh Podcast.

Thank you, sir.

Thanks for the invite.

It’s an honor.

We’re here at the second annual Stars and Stripes Classic lacrosse game, sponsored by the PLL, where we’re going to pit our Green Berets against the Navy seals as they take the field here in a couple of hours under the lights tonight. The Green Beret Foundation and the Green Beret team is here not only to play the game, but I would say, more importantly, to honor our Vietnam veterans, those who came before us in the MACV-SOG unit.

You each served in that unit and for decades, close to 50 years, this has been a part of our history, a part of our lineage as Green Berets that we haven’t spoken enough about for a variety of different reasons. Classification, folks who just weren’t approached the way that they have been in the GWOT era. This was an organization that really set the foundation for what modern-day Green Berets looked like.

It came twenty years after our founders from the Jedburgh teams who went on to form the regiment. You and your brothers and your fellow Green Berets and all the support assets who participated in that mission are owed a debt of gratitude for the service that you gave your country and all of us, and set the example for all of us. Thank you very much. It’s an honor to be here with you, but we got to start by defining MACV-SOG. What was it and what were they doing in Vietnam?

MACV-SOG was designed by the Pentagon with the assistance of the State Department to put reconnaissance teams over the border from Vietnam into North Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia to infiltrate and combat the movement of troops and supplies down the Ho Chi Minh trail. President Johnson publicly said, “We don’t want no wider war,” and we were banned from going outside of South Vietnam. This unit was specially designed to do undercover work over the fence.

When we participated in reconnaissance operations, we did not wear name tags. We did not wear dog tags. We had no identification that we were United States soldiers and without the benefit of the Geneva protections. We generally ran in 10-man teams, 3 Americans, and 7 indigenous, whether they be South Vietnamese, Nungs, Montagnards. We also ran company-sized operations called the Hatchet Force. I operated in both of those capacities as a recon man, as the first sergeant of a recon force.

We are operating for about 1964 to 1971, ’72. MACV-SOG had the highest casualty rate of any US Army unit since the Civil War. In 1968 and ‘69, while I was there, we averaged some months 50% KIAs and 100% WIAs. Teams went out over the fence and disappeared. Our intelligence operations were governed by the Pentagon.

Occasionally, we’ve been told that the Secretary of Defense was interested in a mission or the State Department was, and in some capacity, our ability to bring fire upon the enemy was limited under the direction of the ambassador to Laos, a guy named Sullivan. Sometimes we had to call up to a plane circling in the night. A Blackbird received permission to put some ordinance on the enemy. Jim, is there anything you’d like to add?

Maybe the different types of missions. We did linear recon missions, point recon missions. We did going in to get pilots or people that were killed in the field and we’d go out, get their bodies out and that’s about it. There are probably a few other types of missions. Anything that came up, we’d run out and do them. I ran a seven-man team. I had 5 Montagnards and 1 other American myself.

You both mentioned your MACV-SOG’s requirement, we’ll call it a requirement, but their partnership with indigenous forces. The motto of the Green Berets, de oppresso liber, that puts partnership with indigenous forces at the foundation of what we do. The traditional warfare aspect of what we do is critical to our core foundational mission. Talk about those partner forces. Who were they and why were they so important for you to partner with and what was their capability levels?

There were several groups, mainly the Montagnards. There were different Montagnard tribes. I worked with the Bru, there was the Rhade, some others. We also had some Chinese nuns, which were of Chinese origin and occasionally some Cambodian troops. We were very dedicated to the Montagnards because they were discriminated against by the Vietnamese people. They were mountain people. They did not benefit from any civilization. We trained them up and trained their families up and treated their families well. They were terrific soldiers.

We pretty much just trained them, clothed them and paid them. We weren’t on our mission. We always trained. We trained each day. One of the things I found out about the lot of the Montagnards is that they were there for many years and they worked with other teams before I got there. They were very good. They were well-trained and I learned a lot from them as well.

We had some Vietnamese as well at our reunion in Las Vegas. We brought back Xuan, then Lieutenant Bowra, Vietnamese team leader Ken Bowra later became major general commander of the fifth group. Commander of the Special Warfare Center, Xuan, he was a team leader SOG One Zero, and we went back to Vietnam and we brought him and his wife to Las Vegas to our reunion. We’re bringing him again to Las Vegas. We owe a great debt of gratitude to our indigenous partners. We wouldn’t be alive but for our indigenous partners.

You spoke about the fact that at times, you had up to 50% KIA, and 100% wounded in action. How do you do that? How do you get through that?

Our teams were sent into very hot AOs. The first mission I had, which lasted five days, was the first time that any team had stayed in that AO for more than a night. On the fifth day, we’re awaiting our R1 position and we got overrun. That was one week after the disaster at Da Nang on 23 August ‘68, when we lost 16 Green Berets, 50 more wounded, when we were overrun by North Vietnamese sappers who knew exactly what we were doing there on the beaches of the South China Sea at Da Nang at FOB 4.

They knew we were exfiltrating into the Ho Chi Minh trail and knocking out their communications and trying to bring ordinance on their troops. They knew exactly what they were doing when they attacked us on 23 August ‘68. Just in that week itself, when I was over on a week later on my first mission, we lost sixteen Green Berets at Da Nang. The teams went out and didn’t come back. They were overrun upon landing. It was extremely hazardous.

Was their intel that much better?

The Vietnamese war was highlighted by a lot of enemy infiltration into our ranks. We think at SOG headquarters and Saigon that there were NVA spies or VC spies. It’s very difficult to tell who was the enemy and who was the friend in the Vietnam War. There were multiple intelligence failures. Our job was to collect intelligence on the Ho Chi Minh trail as Americans report back to Saigon and to the State Department and Defense Department in Washington.

I remember when the CCC was overrun over in Kontum. When the enemy came into the camp there, they actually captured one of the guys and he actually came in through the sewer system three times, scoping out the whole area, mapping it out, and went out. I wasn’t at in the camp when it got hit. I was out on the field on a mission when it happened. I don’t think any Americans were killed but they got pretty much all the bad guys. One of the interesting things about Kontum is they had a major road run right between the camp. The camp was on both sides of the road.

One of the interesting pieces, because I know the Green Beret Foundation is interested in recovering some of our remains and the millions of soldiers served in Vietnam, there’s only 1,500 that are missing. Of that 1,500, 150 or 10% were missing because of SOG missions. Of those 150, 50 were our recon guys, our Green Berets, but 100 were our Air Force partners who died trying to find our Green Berets and bring them back.

We have been working very hard with the DPA and Defense Department to recover the wounded. We applaud the Green Beret Foundation for joining in this effort to finding some more remains and bringing them back home. One of the most heartwarming things we’ve done in the Special Operations Association is to attend the funerals of the remains of those, our friends who, for decades, the remains were staying in Vietnam, but they’ve been brought back home. Thank you, again, the Green Beret Foundation for joining in this effort.

That’s one of the big initiatives that we have as really as long as it takes. We had a chance a little bit earlier to sit down with the Green Beret Foundation President, CEO Charlie Iacono, and then our partners from Project Recover who will be working on this initiative with. I asked the question about timeline and rightfully they said, “There’s no timeline. It’s going to take as long as it takes and we’re going to go back as many times as is required. It’s not just about one. It’s about all 58 who are still missing.”

We’ve had several of our members in the SOA, late vice president Mike and Cliff Newman, former president of the SOA, former executive director of the SFA. They’ve gone on missions themselves to places where we think the remains might be.

You both came into Special Operations during the war, but you had to make the choice to join the regiment, apply for assessments, selection. In each of your own perspectives, why did you want to be a Green Beret?

for assessments, selection. In each of your own perspectives, why did you want to be a Green Beret?

Jim, you were doing some stuff before that. I think you came over to the bright side from the dark side.

I served in the Navy for four years before I went into the Army.

I hope you were rooting for the right team today.

Yeah. When I was in the Navy, I spent 22 months in Da Nang driving trucks and working with forklifts and what have you, splicing cables. Towards the end there, I worked with the UDT guys, the Underwater Demolition Teams. What they did is if we dropped the bomb in the water, they would come and go down and I’d blow the cables, they’d pick them up and we’d get it out and stuff like that.

I noticed these guys were going out on missions because I’d go to the chow hall once in a while. I see them walking in all bandaged up and what have you. I figured I’m going to go be a Navy SEAL. That song came out from Barry Saddle, only 3 out of 100 make the Beret. I’m going, “I could do that.” I got out of the Navy and took my battery test as a civilian and went straight into Special Forces. I went from basic to advanced entry jump school up to Bragg, and from Bragg, went straight back to Vietnam and stayed there.

What about you, Doug?

My mother gave me the book The Green Berets by Mr. Moore in Christmas of 1963 or ’64 and I was sold. That’s what I wanted to be. Robin Moore, who was very important with the Green Berets, with the regiment after the war, as you know, he donated a lot of money for the Chapter 38 team house and very active. That’s what I wanted to do.

I dropped out of college with the idea of going to Vietnam, went to infantry school, airborne school, passed this SF qualification test, joined training group and then myself and two other guys were called to the dispensary, Mike Morehouse and Bill Brick. They said, “You wear glasses. How could you be in Special Forces? You could be behind enemy lines with these glasses.” I said, “I’ve managed all these years.” We got thrown out a training group.

The three of us went to Vietnam together. We wanted to go to Vietnam. When we were at the replacement unit at Benoit, a first lieutenant in the Marine came up, said, “Do you guys still want to be in Special Forces?” We said, “Absolutely.” Took us to the training, did the three-week combat orientation course. That’s how we wound up in MACV-SOG. It was this very strange trip, but worthwhile.

Our Vietnam generation post-service has really operated across the entire spectrum of what life looks like for a veteran post-service. A large percentage of our Vietnam veterans have left service and they’ve gone in built corporate careers in the private sector. They’ve led a lot of our government. The post-Vietnam service in as congressmen and senators was tremendous, led by John McCain being one of the most famous ones.

Our Vietnam generation post-service has really operated across the entire spectrum of what life looks like for a veteran post-service. A large percentage of our Vietnam veterans have left service and they’ve gone in built corporate careers in the private sector. They’ve led a lot of our government. The post-Vietnam service in as congressmen and senators was tremendous, led by John McCain being one of the most famous ones.

Some members who still serve now in Congress after the Vietnam War. A lot of industry has been built by Vietnam veterans, but we’ve also seen Vietnam veterans be almost the poster child for dysfunction in the VA, the crisis in the VA healthcare system. The overwhelming of the VA healthcare system. A lot of times, even as the GWOT generation, you can go into a VA hospital and still see Vietnam veterans with mental health challenges. When you look back on the transition from the military post-war, what was your experience?

I had a very good experience. I had a wonderful family and friends. The night I came home from Vietnam, there were 22 houses on our block. Everyone was there to see me. I’d grown up there. None of the dads went to work the next day. They drank too much. We partied until 3:30 in the morning. When I got out of the army, I drove from Fort Bragg back to Philadelphia. This was my home and started college the next day after I was discharged.

I went to college, went to law school, met my beautiful wife, Kathy, over there. I had a great career as a trial lawyer. I’m now a mediator. However, I had friends who had lots of problems. They were caused primarily because our generation, not just us, but our parents and so forth, were troubled by the Vietnam War. For instance, many of us went into American legions or VFW Halls.

They didn’t want us there. We were the losers. They were the World War II guys in the 1970s. Even the VFW and the American Legion made mistakes and they realized that and changed their ways. I remember going to a bar meeting when I was a young lawyer and I realized maybe ten years after I was out of the service, I was not only the only lawyer who had been in the service, I was the only one who went to Vietnam and the only one who got shot at.

It was popular in our generation to escape the duty in Vietnam by wine until the electric service or getting married or going to graduate school. Our generation wasn’t supportive. I’m very proud to say that as I sit here now, starting twenty years after our service, mainly because of the GWOT warriors, mainly because of the Gulf War warriors, the Special Forces, the Special Operations is highly held, high level of respect in our country. I have many people come and said, “I’m sorry, we should have been nicer to you. We should have been more appreciative.” I said, “Let’s just go forward. Let’s appreciate the veterans that are out there today that need some help.”

You went a different direction. You went to another service.

Yeah. When I came back from the 5th group, I joined the 12th Reserve group and I was on A314 of the 12th group. It became an underwater operations detachment. The whole team went down to scuba school and we came back. At that time, I was a police officer in San Jose, California. When I came back, I had a hard time dealing with a lot of the people that leaned too far to the left, but it didn’t bother me. The thing was, it bothered them that who I was.

After that, I was training the Air Force para-rescue guys and submachine guns and night vision devices one day. I didn’t know who they were. They saved a lot of our butts in Vietnam, but I had no idea what pjs were. They told me to come on down to their place. I went down and I was shocked with their equipment and what they were doing, doing rescues every week. When there’s no war, Green Berets, it gets boring. I went and went through a pair of rescue training and became a PJ with the 129th out in California. I did a lot of rescues with them and I loved it. I loved every minute of it. I’d still be in if they’d let me.

That’s still not it because you were in the Navy then you became a Green Beret, served in the Army, you joined the Air Force, served as a PJ and then you became a doctor.

Yeah, then I went to school and became a doc.

It wasn’t hard enough yet.

I’m one of those guys who likes to continue learning. When I did finish my Doctorate thing and I went and had a three-year residency in radiology out in St. Louis, the fortunate thing there is I’m not far from Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, it’s one of the top places in the world for radiology. I used to attend to a lot of their meetings and everything. I went back out to Arizona and opened up a radiology suite when I was there, then I retired from that.

Is there another one?

I went out to become a meteorite hunter, so I go out and hunt for meteorites now.

He’s the most interesting guy I’ve met in the Special Operations. Jim’s endlessly fascinated.

Yeah, I just love it. They booted me out a pair of rescue because I got injured parachuting, but I still skydived after that. I made my last jump in 2002, I think it was.

What happened?

Do you mean from my injury? I got thrown off a helicopter. When I was in Vietnam, I got thrown out of a helicopter about 25 feet. I broke my back in two places and I opened up my SI joint and I didn’t even know it. I just hung around and about a month later, I was back running missions. When I got injured parachuting, it was up in the mountains. It was at night, jumping into the Sierra Madre up there and it was frozen ground. When I hit the ground, I got hurt.

When I came back, I noticed I was having a hard time running. I used to run five miles every morning around the airstrip at Moffitt. The guy said, “If you don’t go to the doc, we’re going to carry you there.” I went to the doc and he goes, “Have you ever hurt yourself before?” I go, “No. Why?” He goes, “You got a bunch of old fractures.” I said, “I got thrown out of a helicopter once.” He goes, “That’s it.” They took me off jump status and they gave me a medical and I got out.

When you look back on your career in Special Forces, in the various branches of the military, what are the lessons that you take forward in terms of leadership and the ability to inspire others and build a team?

You can never train up enough, number one. Number two, I think one of the things that separates us from other soldiers is we never give up. You just keep going and keep going no matter what the challenges are. Try to be the best teammate you can. Look to your left, look to your right, help your mates, get the mission done. If you can’t get it done today, get it done tomorrow. Keep going,

I agree with all that. You can be anything you want to be, just put one foot in front of the other. If there’s a mountain in the way, either go through it or around it or whatever. You can be whatever you want to be if you put your mind to it.

We’re at an inflection point within our ranks within the regiment right now. We have an entire generation from the GWOT who came in post 9/11 days or shortly there before and they’re coming up on retirement. A lot of number of folks I served with and came in with in 2003 have already retired. The rest of them are in senior leadership positions now. We have a lot of folks now within the ranks who haven’t been to combat.

They don’t have the experience that some of us had when we came over to Special Forces. My peers and I had already been to Iraq or Afghanistan maybe once, twice. I had a year as an infantry platoon leader in Iraq before I even went to assessment and selection. There’s a younger generation that’s coming in and they’re fit, they’re smart, they’re ready to get after it. To your point, Jim, there’s not a lot going on right now. There is some stuff going on and they’re getting involved and Doug, they’re certainly training. What’s your message to that next generation?

From Jedburgh to GWOT, we’re incredibly impressed by the service of others. In the Vietnam era, Eldon Bargewell, Billy Waugh, Colonel Singlaub, later General Singlaub. Today’s GWOT soldiers are smarter, they’re better trained, they’re stronger, and they’re going to be better Special Forces, Special Operators than we are. I continued to be impressed when I visited the groups the 5th and the 3rd to talk to the guys who served fourteen deployments.

I know the young guys want to get at it, but we’re having the GWOT guys on our board too. We’re bringing on board the G3 at USASOC. Scott White, we’re bringing on the board retired Brigadier Doug Paul. We have on our foundation board General Bowra who spans the time from MACV-SOG through GWOT. We’re going to have Mark Mitchell is on our foundation board. Mark Mitchell was the first winner of a DSC since the Vietnam War when he led the horse soldiers. I think the modern GWOT soldier has a lot of history to look back on, and they’re going to be better soldiers and better servers, better sources of inspiration for our company than we were. I give them all the credit in the world. They’re doing a great job.

I think to for the people now, what they need to do is if you really want to run the mission, get all the training you can possibly get, fight for that training. If you want to go to Halo Combat Diver, make yourself valuable, and when a mission comes up, they’re going to call on you.

Here in a few minutes, we’re going to head inside the stadium and as the Stars and Stripes game kicks off, you’re going to be honored. You’re going to be honored for your service. You’re going to be recognized for the example that you’ve set for all of us who came after you. What’s that feel like?

We are here for others. We’ve always been here for others. We’re here for you and all our citizens and we’re glad that you’re honoring us, but you’re honoring you and the rest of the regiment as well. We’re not special. We were just there at a time when things were happening. We thank you very much, but we serve for you, sir.

Yeah, it’s all those guys that didn’t come home. I think a little over 50% of us were killed and all wounded and stuff and yeah, it’s for those guys.

Thank you.

Thank you. I know that we’re going to embark. This is the kickoff of our coverage of the MACV-SOG mission and our dedication and our ability to remember them, hopefully bring some home. We’re going to spend, as we said, as long as it takes really starting to dive into this story, really starting to tell it now that there’s more about it that we can talk about. There’s been declassification over the last couple of years.

We’ve been in coordination with our partners at USASOC and the Historian’s Office, who are very excited about being able to really start to share more and more about the efforts of you and your teammates out there. Really look forward to being able to do that over the course of the next probably several years, whatever it’s going to be.

We’re starting to get our team out there from The Jedburgh Podcast and the Jedburgh Media Channel and the Green Beret Foundation to sit down with yourselves again, get into each of your individual stories and really get out to as many others as we can to start to let our ranks now know about the impact that you had and let society know. That’s our mission. That’s our promise to you, that we’ll continue to tell this story and we will make sure that the world knows the impact that you made and from my generation and the foundation. Thank you so much for everything that you’ve done.

Green Beret Foundation to sit down with yourselves again, get into each of your individual stories and really get out to as many others as we can to start to let our ranks now know about the impact that you had and let society know. That’s our mission. That’s our promise to you, that we’ll continue to tell this story and we will make sure that the world knows the impact that you made and from my generation and the foundation. Thank you so much for everything that you’ve done.

Thank you, sir. I hope you can come to Fort Campbell on September 21st when we dedicate the memorial to all the Green Berets who died in Vietnam. Most of them were MACV-SOG guys. I hope you can come there. It would be a very special day. Thank you.

I planned that trip. Thank you.

Thank you.