For centuries society has clung to the classic archetype of men as protectors, providers, hunters, and gatherers absent of emotion and unable to form meaningful relationships. This perception has impacted the interaction and communication not only between men and women but also between men themselves. In today’s world of rising gender equality, many men have lost the ability to understand what it means to be both a “good man,” and a “good human.”

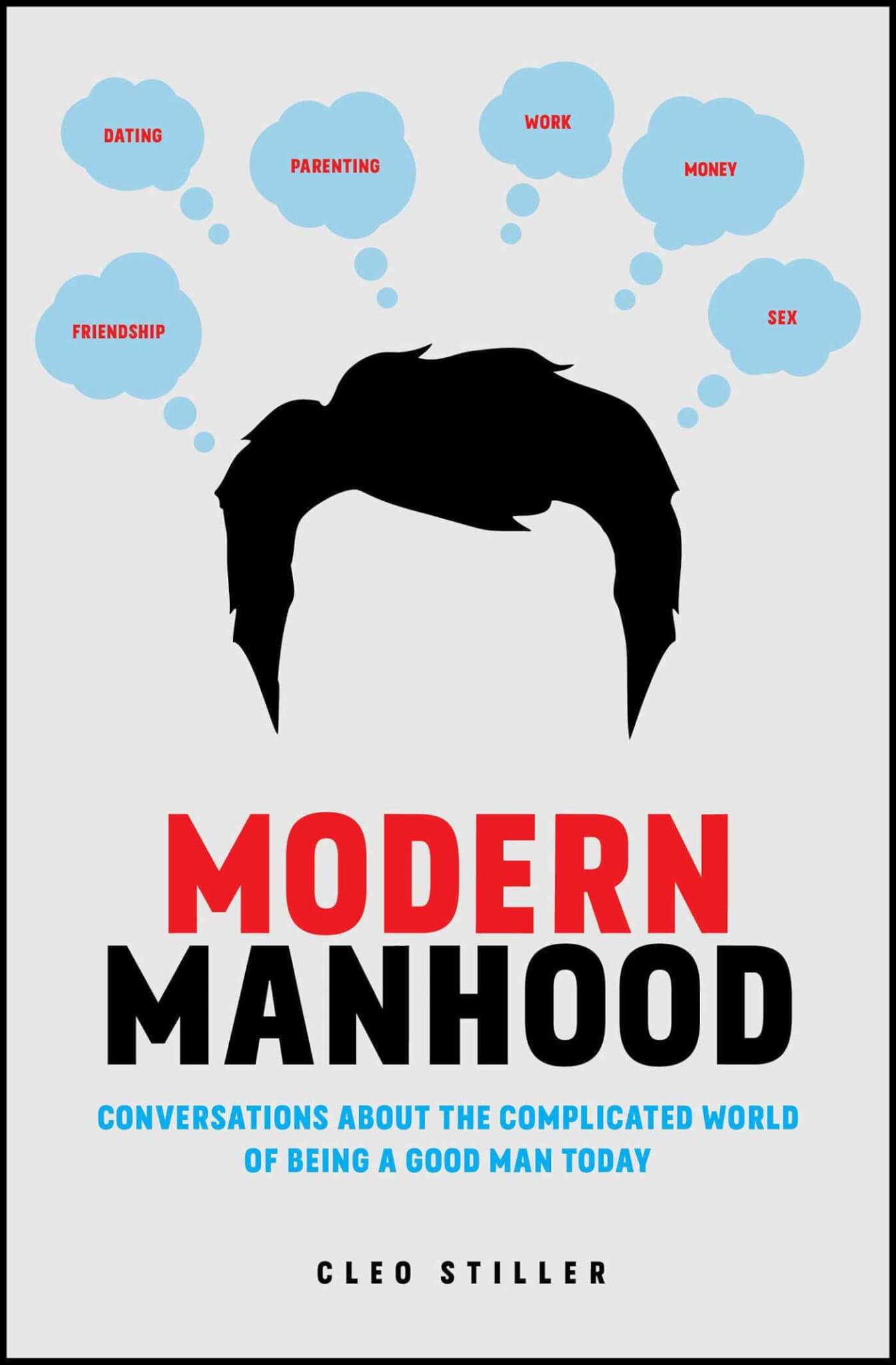

In this episode, Author, & Journalist Cleo Stiller joins Fran Racioppi to discuss her new book, Modern Manhood: Conversations About The Complicated World of Being a Good Man Today and share her thoughts on the artificially constructed “Man Box” in which too many men are caught. She explains how her work in journalism, culture, and anthropology has explored the less discussed topics of sex, relationships, money, and workplaces. Most importantly, Cleo discusses how the #MeToo Movement can help men become comfortable having uncomfortable conversations through an introspective look at their past behaviors and a willingness to do better in the future.

—

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

—

Cleo Stiller is a Peabody Award and Emmy Award-nominated journalist, speaker, and television host on a mission to inspire positive social action around the world. Published by Simon and Schuster, Stiller’s latest project is a new book Modern Manhood: Conversations About the Complicated World of Being a Good Man Today based on years of Stiller’s reporting with men as they reconcile what it means to be “a good man” in a #MeToo era. Prior to this, Stiller spearheaded health-focused digital and social video content for Univision’s cable news network for Millennials, Fusion.

This culminated in the creation of an original docuseries about relationships, technology, and culture. It’s the network’s highest-performing original series and has received multiple award nominations, including a prestigious Peabody Award for public service.

—

Introspection, self-reflection, and accepting when we have failed are some of the most difficult parts of being a leader. Sometimes we’re not proud of the way we’ve handled things in life, but if we acknowledge and own them, the lessons learned from failure can sit right beside the lessons learned from success. In this episode, journalist Cleo Stiller challenged me to not only be a better man but a better human by getting comfortable having uncomfortable conversations. We spoke about the impact of the #MeToo Movement on the communication between men and women. The growth mindset that comes from learning about the Man Box and leaders’ roles in creating equitable, safe, and healthy organizations.

Cleo Stiller is an award-winning journalist, speaker, and television host, and the author of Modern Manhood: Conversations About the Complicated World of Being a Good Man Today, where she unlocks what it means to be a good man in a MeToo era. Harvard University’s Nieman Foundation for Journalism named her work as a 2021 trend to watch. Cleo won a Gracie award in 2015 and has been nominated for Peabody, Emmy, and Cynopsis Awards recognizing her achievements in journalism. Her health-focused television show for Univision’s cable network, Fusion, is the network’s highest-performing original series. Cleo has been featured in Fortune Magazine, Rolling Stone, ABC News, The Independent, PBS, The New York Times, Variety, Bustle, Essence, and many more. She speaks regularly around the country about her work in social impact. In 2020, she was a judge for the Emmy Awards in the category of news and documentary. Modern Manhood was optioned to Gunpowder & Sky for video content production.

—

Cleo, welcome to the show.

Thank you for having me.

I’m excited to have you here for so many reasons. We’re going to talk about your career, journalism, and the book. I got to lay out that this is an interesting episode for me because these topics are difficult to talk about. They are about the uncomfortable things that make you think about your behavior, personality, or approach. They’re critical to leadership and to how we conduct ourselves every day, whether that’s at the workplace or at home. It doesn’t matter.

I tell leaders all the time that they have to get comfortable being uncomfortable, that every situation they face is not going to be easy, and that the answer will not always be clearly defined. The skills that are needed to succeed will not always be something we’re good at and they may not even be skills that we possess, but yet, we must still have the conversation and we still have to act. You’ve built a career on getting people to confront and discuss these uncomfortable topics, what you’ve called and what we call the gray areas. The equality between men and women, relationships, money, sex, workplace divides, and self-health.

I’ve been excited for this episode because your book forced me to think about my actions and I found areas in every chapter that resonated with me. It made me think about the past, present, and future. Yes, it was uncomfortable. At times, I was putting it down saying, “Have I done that? I don’t even know. Maybe I did. I hope I did. I don’t even remember if I did any of these things.” I’ll prove it to you in this vignette here that I have shared the first twenty episodes of guests with a whole multitude of people. People who are coming on the show, who’ve been on the show, and who I tell about the show. I go down the list and I explain, “This is who this person is. This is what they’ve done.” All the time, their feedback is, “That’s amazing. That’s so great. I can’t believe you got them.”

I then tell your story, your background, and the topic. I get, “Interesting,” or no response at all. That’s when I realized I need to double down on this. That’s what tells me that if you’re a visionary, transformative leader, and driver of change, you’re a modern-day Jedburgh. You are forcing even these people that are giving a quick synopsis of what you’re talking about to be uncomfortable without even explaining it. We’re going to bring leadership and organizational design into the conversation around love, health, relationships, and all the things that you talk about. It’s great to have you here. I’m so excited. If you’re ready, I am.

Yeah, let’s dive in.

Your story starts back, in the beginning, growing up. You grew up in a small Upstate New York town. You call yourself an early bloomer. Your parents were open about the lives of adults in growing up and they didn’t shelter you. What was it about growing up in that environment where you were not insulated from adult conversations that shaped your mindset about handling and having difficult conversations?

Due to COVID, my mother is with me, so I’m sure she’ll love this. I have a unique upbringing. My parents are both artists, creative people, and free with many things. I grew up in a conservative town. There’s a point when you’re young and you think that the way you’re growing up is how everyone is growing up, and then the harsh reality sets in. In some ways, you are inevitably different from other folks. I learned early on that in many ways, my parents were different. They were interested in arts and creativity, and that is not so popular in Upstate New York.

I didn’t have a sibling to grow up with, so I was always hanging out with adults. I heard adult conversations at a young age and I didn’t realize that wasn’t normal. Of course, I was young, so I had a lot of questions, so I’d ask a lot of questions and they would answer me. I’m sure adults would temper for an age-appropriate answer. I grew up thinking that you could ask people questions about everything, which would help me in my career as a journalist, but not what do you think about the weather or sports or who’s your favorite team but intimate subjects, which is what interests me. Early on, I was asking people about their relationships, beliefs in politics, and relationships with their money. That’s the through-line on the reporting I’ve done throughout my entire career.

You go on to college in school and you didn’t study journalism at first. You studied anthropology and cultural studies, and then, later on, you made this leap to journalism. Journalism is a tough road. I studied journalism as an undergrad, and then I ran to the army and spent thirteen years there. You look at that route and you say, “I have to go to Bangor, Maine, and do five other jobs in order to figure this out.” That’s tougher. You studied anthropology and cultural studies, and then right after that, you went to Bloomberg as a production assistant and then later, an associate producer. That’s a far cry from two things. One, it’s a far cry from anthropology and cultural studies, but then it’s also a far cry from what you eventually started reporting on. Can you talk a little bit about Bloomberg, why you went there, and the experience there?

I worked at the investment firm for four years, and then about 3.5 years into it, my boss, one of the general partners, took me aside and was like, “You’re smart, so if you want to do this, you can totally do it, but it’s going to be like putting your head through a brick wall.” I was sitting there with quarterly reports in Excel and he was like, “You’re good with people. You should probably get a job that you’re good at,” which is brutally painful advice when you’re in your early twenties, but it was excellent advice. It’s probably one of the most important pieces of guidance I’ve gotten from a mentor. I had to think carefully, “If I’m not going to be Zoe Cruz and take over Wall Street, what am I going to do?” I loved news and I loved asking people questions and having a license to do that. Bloomberg was a great step into financial journalism and they liked me because I had a finance background.

Just like I told you about how I ran away initially from journalism, I also worked in the finance industry when I was in business school. I worked at Merrill Lynch and Bank of America, and I also ran from that.

Towards the army?

No, I ran to run security programs because that’s a difficult road, too. You spent some time at Bloomberg, and then you’re working in the production side of journalism with respect to financial services, but then you go to Univision and joined the Alicia Menendez Tonight show. What brought you to Univision and what was the goal in making that transition?

At Bloomberg, I was their Spitfire producer. In some ways, Bloomberg is traditional, but you always need a couple of young bucks reporting stories that normally wouldn’t get told. For me, my command at Bloomberg once they realized, “I don’t fit in this little box. I don’t want to talk to the Caterpillar CEO at quarterly return time.” My mandate was, “You can tell any story you want as long as you follow the money.” We told stories about the bull run in Spain. We went to Burning Man and told stories about that because they have an interesting economic concept. That’s how I was getting stories on Bloomberg. Eventually, having to follow the money for every story was a little bit limiting for me.

You probably had to stretch at times.

Burning Man’s a great example. At this point, Burning Man has been there, done that. Back in 2012, Grover Norquist hadn’t gone to Burning Man yet and tech was starting to go. I told folks at Bloomberg, “This is going to be big. Our finance guys are going to rush to this.” We were the first financial network to cover Burning Man. Eventually, it got a little tedious. A mentor of mine from Bloomberg went over to Univision to launch this new network. It was a brainchild of Disney and Univision partnering together. She said, “I know you studied women’s health, anthropology, and cultural studies. Would you want to come over and do more human-interest stories? You’ll have to move to Miami for a year.” I thought, “Let’s do it.” That was a great opportunity for me because I was able to rise in my career quickly there. That’s how I got my show.

Let’s talk about that show. The show was called Sex.Right.Now. and you put the concept together for that. I want to get from you how you pitched it because that’s an important part of this story. When we’re creating things, people have so many ideas. You have 1,000 ideas a day and you have to pick which ones you want to execute on, and then from there, you have to even figure out the ones that you can execute on. You have this idea. How did you sell that into the powers that be and the decision-makers there at the network to say, “This is something that’s valuable? I can do this. Believe in me. I have confidence. Give me the green light.”

Honestly, it’s a mix of being observant and then also extremely tenacious. I didn’t start getting a television show right out of the gate. I started by covering stories that I knew no one was talking about on a news level but that everyone was talking about around the country. If you rewind to 2014, the way our culture has shifted in this country is dog years. To remind your readers, in 2014, President Obama was in office and the Supreme Court had legalized same-sex marriage. Tinder, which was founded in 2011, had started to hit beyond the small coastal bubbles. Young people were popping off. It was a crazy time culturally.

What was happening was the intersection of shifting cultural attitudes, somewhat more socially liberal generation, certainly more liberal administration, and then technological shifts, completely shifting how we could meet each other and connect. I told the heads of the network, “Everybody is talking about this. Everyone is like, ‘Is this normal? Do you guys do this?’” The internet is around, so people are flooding to the internet and they’re going to YouTube to be like, “Is this normal? What is happening?” There was so much misinformation out there. I always say no stigma, no judgment. Share the facts. I trust you, the viewer, to use this to your best advantage.

I never tell people what to do. I tell them what’s going on. I said, “If we can capture this market, we’ll be the first to do it and it’ll be a big deal.” We started off as a digital video series that was massively popular, and then they were able to get sponsorship for that. Once you can make money on media, you can do anything. That became the television show Sex.Right.Now. I came up with that title and my dad was like, “What? I thought you were into international politics. What happened there?”

“I made a shift. I changed.”

That show was nominated for a Peabody Award, which is the highest honor in journalism.

I want to ask you about that because the Peabody Award that you were nominated for was in public service journalism and I find the public service part of that to be interesting. Did you view this as educational?

Hugely. That’s the thing. There are other people who had similar shows to mine after mine, of course. Mine was first. They’re up at 1:00 AM going to crazy things. I’m a little bit more of a square when it comes to my beat in general. I viewed our program not as entertainment but as health-focused scientifically-based journalism. That clearly came across in the product. That’s why Peabody paid attention to us. It was a team of serious journalists. The EP on that had come over from NBC Health Journalism. This was an attempt, which is what all my reporting is, to say, “This is an exciting time. There’s a lot changing and a lot shifting, but we want to give people the information so that they can be healthy, safe, and go live their best lives.”

I watched some of these episodes in preparation for this conversation and there’s nothing held back in these conversations. You read some of the titles and you say, “There’s a story about that? I didn’t even think people spoke about those things to each other.” I can understand that. The series does tremendously well. Fast forward a little bit of time. We get into the #MeToo Movement. It launches first here in the US and it gains a lot of global steam. You started to have this call to action from men who are asking you if you’re going to address the issues that are being spoken about. This was a tough time for both men and women, and in so many ways, a real awakening. Can you talk about what these men were saying to you and what they were asking you to cover?

The television show was split about 60/40, 60% male viewership and 40% female, so roughly half and half. It was fascinating that as #MeToo was popping off, in the year that followed, the people who were reaching out to me, viewer-wise, were men because I had developed this trust with men on a show about relationships, health, and intimacy, but it was a safe space for them. They trusted me and my opinion to come to me and ask, “Are you going to do something about this?” Also, the show features people from all over the country, and people wanted to be heard on it.

I heard from guys reaching out saying, “What the hell is going on? I feel like everything I was taught to do is now considered creepy or worse. I have a lot to say, but I’m afraid to say anything because I don’t want to get in trouble.” They would inevitably dive into a situation in their life that was bringing them stress. This would run the gamut from single guys being like, “I have been off the market for a while. I got back on and I am terrified to approach women. I don’t even know what’s okay anymore.”

Coming from Bloomberg, I have a lot of finance and corporate sources, and they were like, “I don’t want to cop to this on the record. When this first thing happened, I was totally in favor. ‘Get Harvey Weinstein in power,’ but now, it’s gone too far. There’s going to be a backlash on this because I know I am not hiring any new female staff.” These are people at SVP levels. They have teams of hundreds reporting into them. “I’m not hiring any female staff. It’s not worth the risk. I sure as hell am not going to mentor my current female staff.”

I had one person even telling me, “My wife told me I’m not allowed to be in a room with a woman who’s under 45.” That’s on the corporate side. I had parents writing to me being like, “We’ve been trying for years to conceive. We’re finally expecting our first kid and we found out it’s a boy. I’m freaking out because I don’t even know what it means to raise a good son anymore. I’m worried about sending him to school. Can they hug? Can they not hug? What is happening?”

The call to action now becomes like, “I’m going to answer these questions. I need to address this.” You’ve come up with a concept that you’re going to write Modern Manhood and its conversations about the complicated world of being a good man nowadays. You focused the book on eight core topics, which are dating, sex, work, money, parenting, friends, self-health, porn is one chapter, and then media. Why these topics? What was important about how you broke those down and the research that had to go in to identify each one of those subsets?

I feel like the elephant in the room is also like, “Why is a woman writing a book called Modern Manhood?” The reason I wrote this book is because these questions were pouring into my DMs and my email. When Simon & Schuster, my publisher, came to me about doing a book for them, they were like, “We want to sign with you. Pitch us some ideas.” This was the last one I pitched because I felt like, “This is going to be such a mammoth, livewire topic. I’m going to get it coming and going. Men are going to think I’m out to get them. Women are going to think I’m apologizing for men.”

In some ways, it was the easiest one that I pitched because this is a crowdsourced book. I didn’t come up with any of the topics. Methodically, because I’m a nerd, I streamlined all of my DMs into one massive Excel doc and I quoted each question topic, and then it became like, “What do people care about?” The benchmark was at least fourteen people had to have asked a specific question for it to even be considered getting into the book.

The book is not necessarily a how-to guide or a clear-cut roadmap to navigating these topics. It’s clear about the spectrum of right and wrong, that sexual assault, rape, and the Harvey Weinstein’s of the world are wrong. Nobody can sit there and argue some alternative or contra argument to that. It also addresses things like the bad date, the blacked-out drunk comments, and the actions that you don’t remember that sit in this area of like, “Was it illegal? No. Was I a jerk? Yeah, probably. Do I remember it? I don’t even know. Maybe I did. Maybe I didn’t.”

It forces you to think about these actions, past, present, future. The core concept of the book is to push for introspection. Think about the times that you were wrong and you were bad to somebody. Somebody walked away from their interaction with you saying, “That’s not a good person to me,” maybe at all or maybe at that moment. Introspection is important to me and it’s a core tenet of The Jedburgh Podcast. It’s one of our core topics that we talk about because it’s critical to define leadership and to achieve elite performance. You have to be able as a leader to look internally and honestly assess that performance and say, “I wasn’t good enough today,” for whatever the reason is, and then own that, and then make changes to do better.

That’s hard and that’s especially hard for men, and that’s especially hard for type A men who are constantly pushing for that next victory. That’s also something that I’ve had to accept in 2020 in my life and that’s why this book resonated and hit home with me. Prior to reading this book and then driving home, a lot of the things that I didn’t know that I knew, I realized that there was a period of time where I was a horrible man, father, husband, partner, and everything in my personal life. I would describe that as my entire 30s was filled with this wild ride of selfishness and extremes where at times, it bled into my professional life that caused extreme chaos in my life.

I spent years not only to unpack, come to grips with, and then even attempt to recover from it, but I also knew that deep down, I was a good person. If I thought about the conversations I had with myself and my family when I was in my twenties, I knew that I was a good person. In 2020, I turned 40 and that’s why I have to wear my glasses now because it made a big change. As I closed on 40, I started to make the commitment that I needed to be better. I needed to be the good person that I was in my twenties. Did I have a lot of great experiences in my 30s? Yes. Did I grow a lot? Yes.

I needed to take those lessons learned, good and bad and own them. Being more mature and more experienced, I now had to set a higher ceiling for my own personal accountability and my own personal responsibility. That started with the introspection and understanding that I sucked. That was it. Just own it. I can’t even sit here and think about all the ways in which I sucked. There’s a million on my mind every day and there’s a million that I didn’t even know I did, but I have to own that, and then I got to make a commitment to changing that moving forward.

There’s a quote in the book from Jason in the parenting chapter that I want to read and then I want to turn it over to you, but it’s like, “Modern manhood means you’re keeping up with the times and not letting your past mistakes define you. It’s standing up for what you believe in and being willing to defend it. It’s realizing that there are people who depend on you and not making selfish paths in life that might be destructive or otherwise reckless.” Can you talk about the concept of introspection, how the book forces the reader to look inwards, evaluate their behavior and actions? Why positioning the book in that manner versus a how-to guide full of judgment and stigma was not the way to position the book?

First of all, I’m a journalist. My big gift is that people trust me to tell their stories. Why they trust me is because I’m not a talking head. One thing I learned with reporting this book is, men do not like being told what to do, which works out well for me because I don’t like telling people what to do. I don’t believe in that. What I did see and hear while I was recording this was that men genuinely were caught off guard by this movement. They were walking around thinking everything was fine and thinking their past was fine. As long as they’re not actively hurting anyone, what could be going wrong?

When all of these stories started to come out and all of this backlash happened, they felt like, “What the hell? I didn’t know this was happening. What is my part in this?” More to the point, “What are the new rules? What can I do? Tell me how I can fix this or be better. I care, but what do I do?” I saw this need because I know having reported on women’s health for over a decade, men don’t care about women’s health and women’s stories. With what’s happening, men do actively want a seat at the table and in this conversation. They care about how our next generation is going to come up and they certainly care that they don’t get dinged for something they’ve done in their past.

I didn’t want to miss this opportunity for all of us to come together, look at our past, our future, and why we do the things we do, and not up-level some of our behavior. The book is based on nearly 100 interviews I did with men across the country ranging from ages of 18 to 62 from a rural North Carolina paper mill worker, South Central LA kid, and everything in between. Also, a ridiculous amount of research and science, then give the reader the ability.

If you’re thinking, “I don’t know what the hell’s going on, but I’m interested and I would like to be better,” this is the book for you because you’ll read it and you’ll start thinking about your past. You’ll be like, “That’s interesting.” I’m not telling you what to do. I trust you, the reader, to decide, “This is how I’m going to use this information. I might have a more thoughtful conversation with my partner at home. I might raise my son a little differently.” That’s totally up to you. It’s certainly not up to me.

That’s a big part of education, especially in higher education. What’s the concept? It’s that you teach people how to think, not what to think.

I’m making an assumption about the folks who read your show, but type A’s typically set the stage for everyone else. For women and men to have better experiences in this world, we need type A’s to take this on and embrace this. Type A’s are comfortable pushing themselves in so many ways, but not when it comes to these more intimate, deep, quiet, personal, sexual, and relational conversations. It’s such a huge growth opportunity. We need you in this.

Introspection is the hardest thing to do for those types of people because you easily brush it off and you say, “Whatever. I’ll figure it out next time.” Rarely do you take a step back and stop in your tracks and say, “Why am I in this situation? Why did I get here? How do I fix it?” Your research showed that men have a more difficult time opening up and discussing their feelings both with others and themselves. Some of the stats that you’ve presented are 60% of depressed men seek therapy versus 72% of depressed women. Men died by suicide at 3.5 times the rate of women. Women cry 5.3 times per month on average compared to 1.3 times per month for men.

Unless you were even growing up in a place where crying was unacceptable if you were a man, then you may be in the zero. All of these are expressions of emotion. These are the release of often bottled-up emotions that have been pent up over time. The way that you have to get rid of them is through this. Can you talk about this preconceived notion of men as a hunter-gatherer, provider, protector, aggressor, absent of emotion, this persona, and then how it affects that communication with women and men?

I didn’t know this going into the book, but as I started talking to people, I realized that all of these classic archetypes we have for masculinity, man as protector, provider, lone wolf, and leader, are so ingrained in us. In many ways, in modern society, we don’t have the same space for them, so it’s extremely confusing. That’s where a lot of the modern manhood gray area questions started coming up. This is so noble. There’s so much about that aspect of masculinity that is fantastic and wonderful. However, there are some drawbacks. I’ll give a specific piece of research that, to me, was the most shocking and women and men don’t know this about themselves, so it’s interesting to learn.

When little girls and little boys are on the playground, they form friendships in the same exact way. They’re all hugging their friends, kissing their friends, whispering in their friend’s ear, and telling their friends all their secrets. At that playground age, little boys start getting pulled aside by their older siblings, teachers, friends, and parents saying, “Don’t kiss your friend like that. That is a girl thing. Don’t hug your friend like that. You don’t whisper to your friend. Girls do that. You hit the field.” Of course, there’s nothing wrong with sports. It’s amazing.

If you only are pushed in one direction and you’re told not to express yourself in these other natural ways, you become imbalanced. There is a researcher named Niobe Way who’s been studying male adolescence for 30 years. She’s got this great social experiment she does where she pulls boys aside as they’re moving from 8th grade to 9th grade and she asks them, “Who’s your best friend?” They can always say who their best friend is immediately. “It’s Johnny.” She’s like, “Great. What do you guys talk about?” They’ll say, “Everything.” She’s like, “What do you mean?” They’re like, “Girls, school, parents, and whatever is going on at home.” She’s like, “I do know that your parents are getting divorced. Does Johnny know that?” He’s like, “Yeah, we talked about it.”

She pulls these same boys aside in sophomore, junior, and senior years. Inevitably, by the time they get to senior year, that one best friend has now loosened into a group of guys. She’ll say, “What do you guys talk about?” They’re like, “Girls and cars.” She’s like, “I know your aunt passed away from breast cancer this year. Did you tell your friends that?” They’re like, “No, I don’t talk about that. That’s way too heavy.” This gets compounded over the years.

There’s a joke in my family that dad has no friends. Mom has tons of friends and dad has the dog, and then it turns out, it’s not just my family. This is pervasive. What we know about the human cognition process is that verbalization is a critical part of that process. If you don’t talk about your emotions, you can forget you have them, which sounds absurd until I describe this scenario. Have you ever been in a fight with your wife and she looks at you, dead in the eye, and says, “Tell me what you’re feeling?”

Yeah, about once a day.

To women reading this show, this is so familiar because women have said this over and over again. It feels like such a simple question. “Just tell me what you’re feeling.” Guys who are reading this, I know that you know what I’m talking about. Your partner feels like she’s up in your face and you feel like a deer caught in headlights. You don’t know what the hell you’re feeling. You want to walk away. It’s so critical for the difference. Men and women are all different. Generally, women are socialized to talk about their feelings with their friends, so it’s easy for women to access the whole range of human emotion except for one, anger. That one is the one emotion that we allow men. Men can’t cry and also, God forbid, men giggle. Women can do those things. What men can do is they can get pissed to angry to mad to furious. That’s all masculine.

You can go from 0 to 10. In fact, we reward that. I came from finance to breaking news and the people who were on top were people who could go from 0 to 10 and who would scream. If a trade went wrong or the story didn’t break right, that’s okay. That’s an acceptable expression of emotion for men. It’s helpful for people to understand that. When it comes to communication, we are coming from extremely different playing fields, and not that it’s natural, per se, but it’s socialized. It’s helpful for people to understand that because what I heard from men the most is that men feel pissed and frustrated. They feel like they’re not seen, heard, and appreciated. The weight of the world is on their shoulders and no one cares.

A lot of these things that you’ve talked about here with relation to men, you put in what you call the Man Box. The Man Box houses all of these stigmas of what a man is supposed to be and what they’re supposed to do. Explain the Man Box for me, but then how do we break out? How do we get men to accept, “I don’t have to be in this box? There is no box.” This is important because this concept of a box is something that is big in leadership. It’s something we talk about all the time that people will say, “He thinks outside the box. She thinks outside the box.” Coming from Special Operations, there is no box. The minute that you start thinking there is a box is when you put yourself or the thought process inside of that. How do we get out?

To me, the Man Box concept was not revolutionary, but it’s been so interesting to me because in having published the book, one of the concepts that men tend to respond to the most is the Man Box.

It’s because there’s a graphic of it. You will look at it and you’re like, “What’s the Man Box?” Conceptually, I’m like, “That seems like really out there.” You look at it and you go, “There’s a list of things in a box.” Now I see it and I say, “That’s the Man Box.”

It is the one picture in the book. The concept of the Man Box was originally developed in the ‘70s by a men’s group based in Oakland but has since been updated for our generation by a guy named Tony Porter. He is an OG who does men’s work and the groups he works with are legit. He has contracts with the NFL, NBA, NHL, and all the ones that matter. People look to type A particularly look to athletes to set the tone for what masculinity is. Tony works with these athletes on masculinity with the hope of having a trickle-down effect.

To the guys reading your show, this is for you. Here is the box and these are qualities of being a man that you must embody. If you do not embody them, you get dinged over and over again by society. Let me know if this sounds like you. “Do not cry openly or express emotions with the exception of anger. Do not express weakness or fear. Demonstrate power and control, aggression and dominance. Be a protector. Do not be ‘like a woman.’ Be heterosexual. Do not be ‘like a gay man.’ Be tough, athletic, and have strength and courage. You make decisions. You do not need help.”

In my 30s, yes. Straight down the line. Absolutely.

You don’t think you have some of this now?

I don’t think that you can completely shed it. I don’t think you wake up one day and you say, “I’m no longer in the box. None of these things apply.” Now, there’s an understanding that you start to understand, “Where do I fall?” Probably each one of these things has a certain spectrum. Now I can start to score myself on that spectrum. “Where do I sit with relation to each one of these points? Where do I need to be that makes me feel good about myself and then make others feel good about me in how I present myself to them? Are we working together to make our relationship better if I understand that I’m going to fall on the spectrum of some of these things?” That knowing helps you to become a better person.

Here’s the thing. Not all of them are bad. Being a protector is a wonderful quality where we have the opportunity to think about that a little bit with current society. Now that we’re not cave people running around being chased by a woolly mammoth, what does it mean to be a protector? Is that something that a man can do? One of the things we talk about in Modern Manhood is if you take the concept of being a protector or provider for your family, usually we link that inextricably with being able to provide financially for your family and being able to physically protect your family from violence.

This comes up in the book. When it comes to money, one thing that we know is, women will increasingly out-earn male partners. Women are pursuing more advanced degrees and that’s particularly true in urban areas. What I was hearing from guys was like, “It’s confusing because I feel like I’m progressive in most ways, but my wife makes $100,000 more than me or $50,000 more than me and it bothers me.” They were self-sabotaging their relationships in other ways because this core issue was a problem for them. It was even surprising to them that the amount of money they made had such an impact on their worth as men.

I’m using this as an example because you can use this formula to think about other things in your life. This idea of being a provider for your family is a noble concept and we should not throw that out. The truth is both women and men have the instinct to provide for their family and we’ve associated male providership with money isn’t naturally ingrained in us. When we were Neanderthals, men hunted, but that was a luxury good. I’ll use modern terms. Meat only came around once a week. Women provided as well. They provided the daily fare of nuts, fruits, and berries. Dual income households are the way that women or men are wired to interact.

If you’re reading this and you’re in a situation where quarantine or COVID has perhaps caused you to lose your job and you feel depressed and you’re not a man in the role of your family or your income. Maybe you still have your job, but some of the projects you thought were going to come through didn’t come through because many industries are tanking. When I asked women about this, it turns out that there are so many other ways you can provide within your relationship besides money. If you’re having that impulse like you feel less of a man because you’re not bringing that home, there are so many other ways to provide. That can be picking up stuff around the house, helping your partner with child care, family care, lawn care, and all of this stuff. It requires us to communicate in ways that we haven’t done before.

It makes everyone better.

Sometimes, asking your partner like, “This is hard for me. This is how I’m used to being. I know this is temporary, but what can I do in the meantime because I need to feel like I’m providing for this family?” That introspection, vulnerability, and communication can change your relationship in incredible ways. It’s a way that you keep the quality of the Man Box, but you’ve completely revolutionized it because you made it work for your life right now, so you’re living outside the Man Box. Does that make sense?

It does. You’re moving to a part of that spectrum somewhere in there that makes you more contributing to the overall good of the home.

The point of the Man Box is that if you haven’t cried in five years, you’re not living your best life.

Maybe you haven’t challenged yourself enough.

I interviewed so many men and I asked them when was the last time they cried and they didn’t even know. Maybe when a pet died when you were a kid, that had an impact on you.

Let’s talk about that a little bit more because part of that shield that goes up comes from this separation that you talked about as an adolescent where you’re open with your feelings and you’re open with your friends, and then you devolve as you get older. You separate away from the close intimate relationships to this more circular type of friendship. That then devolves into what you call locker room talk where your conversations with your friends as a male are about women and work. They’re superficial. There’s this bragging that goes on about how much money you have, how many women you’ve been seeing, or something like that.

How do you define this locker room talk? Talk a little bit about that. I got to challenge you on that. I took a note in the book when I read it. I think about the show Sex and the City, which was a great show showing that women have these conversations in the same way that men do. In the book, you talk a lot about how this perspective of men having this is something that has created a challenge to communication in society. Don’t men and women both do this? What’s the difference?

It’s nuanced and this is not black and white. This is completely a gray area, contextual and specific. I heard from so many men being like, “I have a friend that says racist, sexist stuff and we used to let him get away with it and laugh it off. With everything going on right now, I don’t feel like that’s okay, but I don’t know how to call out my friend because I don’t want to create waves. Also, I don’t want him turning around on me and being like, ‘Are you perfect?’ Because we all know we’re not.” The question then becomes, “Why do you guys talk like that?”

What I heard from guys was like, “Please do not take away my locker room talk because that’s all we got.” Sometimes, women have this work-husband, work-wife relationship. They’re like, “I don’t have that.” I can’t roll in and be like, “My wife and I haven’t connected in six months and I’m frustrated. I can’t meet any of my deadlines.” All I’ve got is pointing out how the young woman in the office is looking good in their outfit and that’s how we’re going to bond, or the game that was on last night is all we’ve got. Don’t take that away from me. Do women do that? Absolutely, for sure.

This is the story I want to tell. Jim writes in and Jim was like, “I’m a dad. I have a boring dad life. I’m 42. A lot of my dad friends are woke. I’ve got this one dad friend who’s not woke and he’s out there. In a way, that used to be entertaining but these days, it makes me uncomfortable. Every time the couples get together, this one guy in the group is always starting things between the sexes as if there’s this mad gender war happening. The husbands have to be on one side of an argument and the wives have to be on another. This guy makes jokes. He calls his wife, ‘my future ex-wife.’”

In ways that Jim said, it was refreshing because it’s so bold, but one night, the two couples were out to dinner with their kids and they’re sitting at the table at a Greek restaurant. Jim is sitting next to his friend and the wives are on the other end of the table and they’re talking to each other. Jim’s friend leans over and nudges him to look below the table. Jim does and his friend is holding a naked photo of a young woman and looking at him like, “She’s hot, right?” Jim is totally confused because he’s like, “What the hell is going on? Our wives are right across here. Who is this girl? Are you having an affair?” In his mind, he’s like, “What do I even do with that? The question is, why is this guy doing this?”

The theory behind it is that this guy would like to connect with Jim. They’re buddies and they like to hang out, but his default mode is to go into this one way of communicating, which we’ve sanctioned for men. You can talk about work. Everyone jokes about this. You can talk about your bygone days. What if we allowed men to have more emotionally vulnerable conversations so that you weren’t defaulting to this all the time? Women generally do this. It’s not saying that you’re not going to find four women at brunch discussing the size of their hookups from the night before. You will, but they’ll also be talking more deeply about how that experience made them feel and how past experiences have made them feel.

One thing we talked about in the book, an example was someone was like, “Am I not allowed to talk about the bodies of the people I’ve been with?” It’s a gray line. “Is it disrespectful?” It’s locker room talk like, “Does it hurt anyone? If she never finds out, does it matter?” The idea is if you only talk about the bodies of the people you hook up with and you’re not talking to your friends about how it makes you feel or the experiences make you feel, that is a problem. If you’re doing it also coupled with a deeper conversation, fine. Does that make sense?

It does. There are going to be times in these conversations where you’re not going to agree with the comments that are being made, actions made by other men, things that they talk to you about, and things that they show you. Challenging them on it is hard. You’ve talked about this concept of like, “If I challenge them on it, are they then going to look at me and say, ‘He’s not in the box. He’s not a man. He’s less of a man. He doesn’t agree with me.’” There are times when you look at people and you say, “That guy’s shitty. What they did is bad and wrong.” You threw out this concept of call your friend up, not call them out. What does that mean?

I talked to this guy, Brian Stacy. He does men’s work now, but he’s formerly applied to work with the FBI. He’s the classic man’s man, 6’4”, college athlete, etc. He said when he was in college, he hooked up with many women. With their consent, he would videotape their interactions then he would keep them for his personal records. Without their consent, sometimes he would show the videos to his friends. This became legendary in his friend group. They call it the B files or something and he had this for years. His feeling was like, “If we made the video consensually and it’s a small group of friends that I’m showing, what’s the harm?” He wasn’t emailing the file. He shows them on the phone. He had the B files for years.

When Brian had a come-to-Jesus moment and was like, “I don’t like how I’m living. This is not authentic,” he decided to delete the B files. His friends were like, “What are you doing? We live for your files.” He explained to them, “I’ve been working a lot on dealing with my own ways of how I’m showing up and that felt shitty and I’m not doing that anymore.” I tell that story as an example because when your friend says something shitty, what they’re probably trying to do is bond with you in a way how you guys have done it forever and is socially acceptable for men.

We don’t want to be having the same conversations in a decade. You don’t want this friend to be talking about this ten years from now. Instead of calling them out, you can let them know, “I know you’re telling me this because you want to share something with me. I totally get it. All good. Just a heads up, I’ve been thinking a lot about the stuff I’ve been sharing and how I’ve been communicating with you guys. I’m not going to do that anymore. It makes me feel like I’m putting women down, which I’m not super down with.” You can amend this.

Own that it’s your journey. You don’t have to get super deep and it doesn’t have to be super touchy-feely. Just being like, “I totally hear why you’re talking with me like this. I’ve been thinking a lot about it. I’m not going to do that anymore.” Do not go on and on about it. It’s one sentence, and then be like, “How’s it going with Sharon?” Punt the question back to something that is more honest, intimate, and reflective. It doesn’t have to be a big deal. You don’t have to get on a soapbox.

This how is interesting because the hardest part is you have to make that transition. Leadership is about standing up for what’s right. In the military, we call it choosing the hard right over the easy wrong, which in itself is difficult because the hard right by nature is uncomfortable. It’s easier to sit back and say, “I’m not going to do anything. Let it go. I’ll keep my mouth shut. Nobody judges me.” I’ve dealt with this a lot in building security officer programs. It’s challenging as a security officer to go up to somebody and say, “You’re not doing this right.” It’s easier to sit back and say, “Let them go by. Sure they have a visitor but that’s okay. It’s probably their spouse or their daughter. We shouldn’t interrupt.” You’ve got to be able to initiate these difficult conversations and men are often terrible at this at a higher rate than women are. It’s how you make that leap. Addressing it is one way and another way you talked about was humor.

What we’ve learned about how men prefer to communicate is they’ll let it go, then they blow up. That leaves no nuanced or more subtle forms of communication. Humor is such a wonderful way to communicate. The truth is everything is awkward and uncomfortable. You can totally lead with that and be like, “This is totally awkward, but I’m going to be upfront. I know this is going to make me sound a little lame, but I’m not doing that right now. I feel like we were both better than that,” and make a little joke. It’s also a tactic I use to ask intimate questions. I’ll be like, “This is awkward, but I got to ask.”

I want to bring it up here because it’s an interesting story that I have, which I wasn’t planning on telling, but I might as well because it came up. This happened to me because I come from a world where you’re faced with monumental challenges all the time. At the point in which you learn that there’s something extremely difficult that you’ve been asked to do, you have to figure out a way to internalize that.

One of the ways in which I, in my personality, internalize that is when somebody presents me with a complicated problem that I may have looked 5 to 10 steps down the road and said, “This isn’t as easy as they’ve briefed.” I’ll smile or laugh because that’s my deep breath. “How do I take a step back?” You assess it and you chuckle a little. This got me in trouble once because I was being briefed on a complex plan by a ten years younger female in the office. They needed my organization’s help to pull this off. When they said, “What do you think?” I had thought about these 30 things that had not been thought about in the presentation to me and I gave that, “To me, nothing.”

I got a call about an hour after that meeting from my boss and he said, “This happened. She believes that you laughed at her because she’s a woman.” I was absolutely shocked and I said, “I don’t understand what you mean. I don’t even know what I did.” He’s like, “I didn’t notice it, but apparently, you laughed at her when she presented it.” I said, “In no way did I laugh at her. I got briefed on an absolutely ridiculously complex operation and was told that I needed to execute it in a short amount of time. That’s how I internalized it.” I did go and have the direct conversation and apologized, “I didn’t mean it. If I offended you in a way, this is how I internalize things.” To me, that was a big wake-up call because I had no idea.

This is a great example of what I hear from guys all the time, which is, “I feel like I’m walking on eggshells. I’m being me, and then I’m getting called and told I have laughed at a junior female employee. That was disrespectful. That was not my intent at all.” First of all, I completely hear you on that because I also use humor as a defense mechanism. It’s okay that you fucked up like that. I don’t even know if we would say it was an eff up, but if you hurt someone’s feelings, I’m sure you don’t want to do that. Let’s say you screwed up.

That’s fine. This is going to happen. That’s part of the point of the book. You’re going to mess up on this road to being a good modern man. The thing to do is exactly what you did, which is call and apologize and say, “In my head about it, I apologize.” What your takeaway from that can be and I hope is, is that things that you would be oblivious to previously, you have to be a little bit more mindful now. Hopefully, if we’re all more mindful about this over the next several years, then it will dissipate. It is true optically that to have a more senior man laugh after a junior female has presented is not good optics. We know because there are decades of women not being taken seriously. It might not have been your intent, but it’s how it looked.

That was a tough one because I thought the project was cool.

All you have to do is call and you have that conversation. I’m sure that they’re like, “Cool,” and then you move on. It’s not the end of the world.

What I wanted to do is a little bit of a lightning round and we’ve talked about a bunch of these concepts. They’re the stigmas. They’re 5 or 6 difficult conversations. I’m going to throw out the phrase, the sentence, the couple of words, and then I want you to quickly come back to me with the first thing that comes to mind. This is the how-to. I know we said we didn’t create a how-to, but there’s got to be a little bit of a how-to. It was maybe not how to do but how to think. We’ll run through this. I’m going to throw them out and then you give me the first thing that comes to your mind, which is the how-to. First one, male leaders are avoiding one-to-one meetings with female employees because such an allegation will ruin their career.

If you behave properly, statistically speaking, you do not have to worry.

Two, men must script every word that comes out of their mouths and censor every action.

Absolutely not. Just think before you speak.

Three, chivalry is dead. Being a gentleman is no longer a thing.

Absolutely not true. Being a good person is always in fashion. Anything that you would extend to a woman in the know of chivalry, extend it to everyone, and then your bases are covered.

Four, there’s nothing wrong with a stay-at-home dad.

If you like being a stay-at-home dad, be a stay-at-home dad.

I would love to be a stay-at-home dad. I tell my wife all the time, “I would be the busiest stay-at-home dad you’d ever meet.”

A type A as a stay-at-home dad is a dream.

Five, financial feminism is the path to independence and equality.

Financial feminism is the idea that women need to be financially independent and have a good life is right for some women.

The last one, acknowledge harm, repair the harm, transform.

The motto for every person going forward.

We’ve provided a bit of the how-to. I like it. We talk about talent management a lot here and we talk about the nine characteristics of what Special Operations Forces recruits, assesses, and selects for. It’s strive for resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, team ability, effective intelligence, emotional strength, and curiosity. You have to demonstrate all of those at different times to achieve elite performance. Not all at once. You’re going to have different combinations of them. Generally, you have to have some component of each one of those things. You have defined how to be good as not being a function of being a man or woman. What are the characteristics of a good human nowadays?

Largely, the characteristics you listed, compassion, courage, perseverance, resilience, mindfulness, and strength. We’re not far off.

We got work to do. We have to change behavior and changing behavior is not fun. To get everybody into those worlds, whether they’re your list or my list, they’re fairly complimentary. We could do an analysis, lay them side by side and a one-to-one comparison. Changing behavior is hard. It takes practice and commitment. Small changes every day and incrementally will bring on future change down the road. You look back and you go, “I can’t believe we came so far.” It’s especially difficult for leaders of organizations who not only have to consider their own actions every single day. They also have some level of responsibility and accountability for the actions of their teams and subordinate leaders that work for them.

You have a quote, which I put into context, but yours is much better than mine. “Micro changes can make massive differences eventually. When they start happening on a massive scale, that’s the change we need and that’s where we need to go.” How do we develop this growth mindset every day and commit to it? What do we tell leaders of organizations and teams to say, “You got to keep the growth mindset every day? You got to do these couple of small things,” but also, we got to be real and rational. We can’t go off the other end and wrap ourselves in bubble wrap. Don’t speak unless spoken to, one-word answers, and then enter this world where we can’t achieve anything because everyone’s afraid to look at each other. It’s almost like when COVID started, you didn’t want to look at anyone. If I make eye contact with them, I have COVID.

My first recommendation is that leaders should get clear on why they’re doing this because if you’re not clear on why you’re doing this, then you’re going to fall off the second it gets hard and it’s going to get hard immediately. The reason why leadership needs to commit to making the changes that we discuss in Modern Manhood is because you are genuinely and passionately committed to having the world be more equitable, safe, and healthy for women and men. What we’ve discussed here is this system where we operate in. It hurts both.

If you do not want to have this conversation with your daughter in fifteen years, that’s a good motivation. If you don’t want to see your son get dinged for something that you know you screwed up in, in your past, that is a strong commitment. You have to be clear on why you’re doing this. It’s why I wrote the book and why I talk about this because it will kill me if in several years, I’m having these same exact conversations. First, get clear on why you’re doing it because every time that things get tough, you are going to wonder why and you have to get clear on the core.

First of all, that’s why you’re doing it. Second of all, get comfortable being uncomfortable. We are talking about centuries of behavior that never got up-leveled. People who like history and science, you’re going to love this book because it teaches you so much about why we are where we are. It’s not a mystery, but good to know it. Centuries worth of behavior isn’t going to be unlearned in a decade. You have to know that you’re strapping in for the long haul and you’re going to mess up, and that’s okay.

For example, at a leadership level, I’ve developed the work chapter into a corporate workshop. What I do with leadership is one idea that we have when you’re in leadership is that you can’t ask questions of your team because you have to have all the answers. It’s a huge mistake and it’s not going to work anymore because your team is going to have a certain perspective about how things could change to help them that you might not know. You’re not expected to know because it’s not your life experience. Why would you know?

For example, it’s a great idea to pull your team separately over email or whatever. It doesn’t have to be directly talking to them if you’re not comfortable doing that. Sending them an email and being like, “I am committed to making shifts in the way our team is working. My head is not stuck in the sand. I see conversations happening globally right now. It’s important to me that we show up as the best team possible while also managing productivity and efficiency. If there’s something that you have an idea of, shoot me an email and let me know and I’ll incorporate it.”

People have ideas. When I talk to leadership, I’m also talking to the staff. Everyone’s got an idea of how it would look. Some of this will be using a lens that you have not previously thought of before. Everything is specific to the team, but there’s a certain way of doing business that we have and you don’t question it. This is the time to question what the impact of that may be. If you are used to getting together for later at night or dinners or weekends or something, that behavior, while it’s usually fun, also limits the accessibility for people that are responsible for child care and home care. It often tends to be your female team members.

I’ve heard from guys, “Do not take the happy hours from me. I love grabbing a couple of drinks after work.” I’m not saying you can’t drink with your team, although maybe you should not, but if you’re going to do it, do it from 3:00 to 5:00. There’s no reason that you can’t shave off two hours off your workday if you’re running an organized team. That way, you’re still sending people home at the time that they would need to be responsible for home.

There’s a lot of other ways like communication, meeting structure, and mentorship. We talk a lot about mentorship. There’s a lot of ways that you can tweak how you’re interacting with your team that will make massive changes in the success of the women on your team. You’re not expected to know everything, so ask and do that thing that we were talking about where you can be like, “It’s a little awkward. I grew up in Indiana in a small town. We didn’t talk about this, but I’m committed to doing better so let me know what you need and I’ll take it into consideration.” That leadership is so rare.

I hear from so many people that if they knew that their senior was seeing and hearing them in that way, it would make a fundamental difference. That’s what I advise. That’s the work I do for leadership. We do role-playing and stuff. The one thing I’ll end with because it comes up from all men is that there’s apparently this urban legend of a woman who will walk around where if you hold the door open for her, she’s going to freak out at you. I heard from guys all the time, “Things are so crazy right now. I don’t even know if I’m supposed to hold a door open for a woman because she’s going to lose out on me.”

The question is, do you want to hold the door open for the woman coming up behind you? I hope you say yes, but the question is why? When I ask a lot of people, they’ll be like, “I don’t know. It seems like the right thing to do. It’s how I was raised. It’s chivalrous and noble.” These are all great qualities. We’re not trying to lose that, but the updated version of that is if you’re going to hold the door open for the woman coming up behind you, hold the door open for anyone coming up behind you. That is what a good person does. That’s simple behavior.

What makes us feel defensive about it is that we don’t know why we do it, so we’re like, “Is this right? Is it wrong?” Once you’ve decided that you’re the dude that shows up in the world holding the door open for anyone who comes up behind him because that’s what a good person does, then say you run into this urban legend of a woman who yells at you for holding the door. You’re not going to be bothered by it because you already know. You can just say, “Sorry, I didn’t mean to ruin your day. I hold the door open for everyone.” You walk away and you know, through this modern man lens, you are showing up as a good guy.

This will be interesting as the world comes back from the things that you haven’t even thought about for the last bit. The book has been at the top of the charts since it was released and you’re working on a v2 and some updates to it. You’re doing some research. I told you I have a recommendation for you and you hit on so much of that recommendation. I would love to see a bit about leadership there and a bit about how organizational leaders tackle these challenges. We’ve had a few years where a lot of these things, you haven’t had to think about as much as you have when you’re in the workplace every single day.

As we get out of the Zoom world, this is an interesting time because we’re going to be coming back together as societies in 2022. Society has never been more divided on the basis of politics, race, and gender. So much has also happened in this time, but we’ve been separated and now we’re coming back together. This is an interesting time in 2022 and beyond where we can all up level and we can all call each other up to do better.

I talk about the Jedburghs in World War II and I talk about the fact that they had to do three things every single day to be successful. They had to shoot, move, and be able to communicate. If they could do those things as a foundational basis for everything they did, it didn’t matter what challenges came their way. They would find a solution to solve them. What are the three things that you do every day to win and be successful?

I’m regimented for someone who’s so creative. My three things have to happen within the first 30 minutes of waking. Otherwise, the whole day is shot. I have to journal, have coffee, and have to exercise. If I mess with that component, it’s all shot to hell.

I finish this where I take the soft attributes and I assign everybody who I speak with what I think their core soft attribute is. This was difficult for me. The soft attributes are drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, team ability, effective intelligence, emotional strength, and curiosity. You 100% exhibit all of those or I wouldn’t have had you on the show. It’s the prerequisite. I try to narrow it down and I look at two for you. I think about curiosity in your life as a journalist and I talk about integrity because if I were to sum up, how do you become a good person? How do you define a good person? How do you achieve this social movement and these cultural changes that you’re talking about? It comes down to understanding what’s right and to me, that’s integrity.

Curiosity is exploring the unknown, questioning the status quo in pursuit of better, and this continuous growth attitude. Integrity is defined as understanding what’s legal and right and aligning those to your actions and your words. You’re the first guest that I can’t decide, so I have to give you curiosity and integrity because of your dedication to the advancement of social justice and cultural transformation. You’re forcing the hard conversations that people don’t want to have with each other or with themselves. That truly is transformative leadership. That’s the forcing of change.

You’ve said it’s complicated and uncomfortable and it won’t happen overnight. There are no shortcuts. I couldn’t agree with any of that any more than I do. I want to close with two quotes from the book that I take away and I think about these every day. The first one is, “You have to choose courage over comfort.” All of us need to allow for vulnerability and imperfection. The second one is, “When internal personal desire becomes greater than the resistance or risk that’s outside, that’s where change happens.” I thank you for coming on the show, for driving this conversation forward, and for making me uncomfortable by becoming more comfortable with it. I hope that everybody will take a little bit away from this conversation and get a little bit better today than they were yesterday.