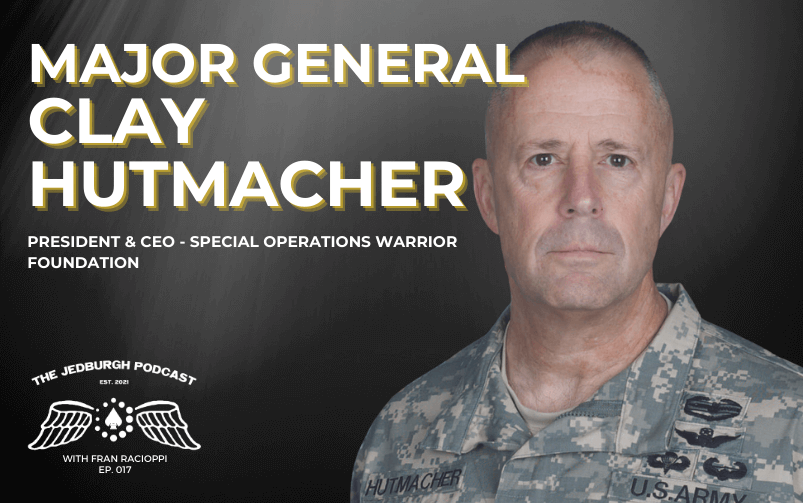

Are leaders born or made? Major General Clay Hutmacher believes that leadership is a learned skill. He spent 41 years in the United States military commanding the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment; one of the most lethal projections of combat power the world has ever seen. Precision execution is required every second of every day to assume – and succeed – at the extreme level of risk at which this unit operates. Major General Hutmacher is now the President and CEO of The Special Operations Warrior Foundation where he has dedicated his post-military career to providing education to the children of our fallen Special Operations warriors and Medal of Honor recipients.

MG Hutmacher joins host Fran Racioppi, and special guest host TWG Founder and Navy SEAL Mike Sarraille, to discuss raising the standards of leadership, the importance of organizations creating expertise across functional, technical, and strategic thought domains, realistic training, and the balance between mission and people when the mission calls for relentless dedication.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

—

MG Hutmacher became the President and Chief Executive Officer of the Special Operations Warrior Foundation in September 2018.

He was a career United States Army Officer and retired in 2018 having served over 40 years in uniform. As an Army Special Operations Aviator, he commanded at every level during his three tours with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, where he served as the MH-60 Direct Action Penetrator platoon leader, company operations officer, executive officer and commander of 1st Battalion, Regimental Commander, and the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Special Operations Aviation Command.

MG Hutmacher’s last active duty assignment was the Director of Operations in the U.S. Special Operation Command, Tampa, FL. His previous assignment was as the deputy Commanding General of the United States Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg, NC.

A native of Wenatchee, Washington, he was awarded a Bachelor’s Degree in Aerospace Management from Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, a Master’s Degree in National Security and Strategic Studies from the United States Naval Command and Staff College, and a Master’s Degree in Strategic Studies from the United States Army War College.

—

General Hutmacher, welcome to the show.

Thanks very much for having me.

It’s an honor to finally meet you. On the show, we provide leadership lessons on the impact of transformative leaders. For more than 41 years, you served our country. From an enlisted Marine, through an Army One Officer, to a Commanding General as a Commissioned Officer. You spent the majority of your career leading at all levels. Not only the most elite units but the world’s most lethal, tactical through the strategic deployment of power, the 168 Special Operations Aviation Regiment, the Night Stalkers. An organization that you transformed through decades of your leadership. Also, an organization that has shaped global security and the outcome of many conflicts throughout time. Sir, it is truly an honor to be here.

Thanks. That’s quite an introduction. I never thought of myself like that but I appreciate the shout-out.

As a Green Beret, I was fortunate to work with the 160th and many of the folks under your command. As the commander of the 160th, your motto was “We exist to support the operator on the ground no matter what.” In that vein, I’ve asked Mike Sarraille, author of The Talent War, and the Founder and CEO of The Talent War group to join me. He is also a guest on episode one, but former Navy SEAL. We figured we would put you to the test as the general, as the commander where you now have to sit here and deal with the both of us.

If I leave here with my lunch money that I’m in here in an interview with a SEAL and a Green Beret. As long as I don’t get my pocket picked or get a wedgie or something, I’m happy. I think this will be a success.

I can’t guarantee you that.

That sounds like the beginning of a joke. That’s the difference between a 160th SF guy and a SEAL in the bar.

I thought it sounded like a challenge.

There are many places we could start. Since you and Mike both started your careers as enlisted Marines. I figured we start there. You said that you entered the Marines at seventeen years old because you need direction? Why did you enter the Marines?

I was living in a foster home at the time. I dropped out of high school. Most people would say that my future was looking pretty bleak. I realized that myself. The foster family I was living with, the Father, Charlie Williams, who has since passed away, was a Korean War vet who served in the Marine Corps. He often told stories about his time in Korea. A lot of great stories, some are unsettling, about his experience in boot camp. I just realized, “I needed something like that in my life.” I wasn’t quite sure if that was the right answer but it was the only one that I felt was available to me.

I joined the Marine Corps and went out not knowing what to expect. I’ve said before with other folks that it wasn’t the warm embrace that I had hoped for when I went down there. My bus arrived at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego. I remember hopping off the bus onto the yellow footprints. They had the articles of the Uniform Code of Military, Justice Select articles on the wall and they read them to us. That way you’re accountable. If you do anything wrong at that point, you’ve been briefed and “You can’t say we didn’t tell you.”

I’ll never forget the last article they briefed us on was Article 134, which in the UCMJ is called the General Article which covers all the cats and dogs and stuff like that. The way the drill instructor described it to us was that article right there, the general article, “If you do something that pisses us off, we can prosecute you under that article.” That’s what they told me. I was seventeen, I’m like “Okay.” I took him at his word. It was a painful process initially but it was the right thing for me.

What were some of the leadership lessons that you learned there, some of the things that turned your life around at that point?

Resilience and sticking to it. The first few days were like hell on earth. The first night we got there, our plane landed at 7:00 PM or 8:00 PM. We got our heads shaved. I’ll never forget that.

Mike still shaves his head.

Yes, I can see that. He is maintaining the Marine Corps standards on haircuts, not with facial hair.

Trust me, I hear that from my father all the time.

Anyway, we get our hair cut. The barber was like, “Do you want to keep your sideburns?” I had relatively short hair anyway. If you have long hair, they’d shave around and leave a big tuft of hair. They left you like that for 6 or 8 hours and you’ll look like a circus freak or something. We were up all night inventorying. They gave us these net laundry bags. Everybody’s in red bins and everybody holds up one razor, “Look, Hutmacher’s arm is sagging so we’re going to hold the razor up for another ten minutes,” and you have a hundred things in these bags. The next morning, we’re sound asleep and exhausted. The next thing I know, it’s like Armageddon. They’re pulling people out of the racks, throwing them on the floor, throwing trash cans everywhere. That initial thing was unsettling for a seventeen-year-old.

There were certainly times in my old mind that I contemplated quitting. I saw several people do it but there was something in there. I never wrote home and told my parents that I made a serious mistake, even though I firmly believed I had. I felt like I had to get through every day. It was one day at a time. I wouldn’t say it got easy until maybe the end. It was my first real challenge in life and I made it through. From that, it was the foundation that I could build on future successes. Whether it’s pursuing education, and seeking self-improvement.

Tenacity and commitment were some of the lessons I learned early on. I give props to the Marine Corps. They’re very disciplined. More so probably than the other services. That’s my personal opinion. That served me well later in life in the Special Ops community. A blending of the Army’s philosophy and the Marine Corps was critical for me in my journey of leadership development, which I’m continuing now. Those were probably the opening things that set a good foundation for me.

What year was that?

I joined in the delayed entry in December of ’77. I went active on January 3rd or 4th, 1978.

The process sounds like it has not changed. It was the same in 1998 as what you just explained and how that tradition holds. That’s a legacy.

I suspect they don’t do the physical abuse like they used to do.

No, they did not.

I’m not trying to paint the Marine Corps in a bad light. I’m sure that happened in the Army and everywhere else. It was real. The threat of getting your butt kicked was there the whole time. I tried my best to maintain a low profile. Failing periodically with expected results. There was a lot of slapping around, punching, doing stuff like that, that I don’t think exists anymore.

Seven years in the Marines?

[bctt tweet=”Leadership is a learned skill.” username=””]

Six and a half. I got out. I formally signed out of the Marine Corps in May of 1984.

You had identified this opportunity to go into the Army as a Warrant Officer.

I was stationed at Marine Barracks, Whidbey Island, Washington. It was long since closed. There was a Marine Corps Reserve Huey unit on the base at the time. I was a bouncer in our little enlisted club, it was called the Globe and Anchor Club that was in the corner of our barracks. This guy was sitting there having a beer. He had a brochure on the table in front of them. I was walking through and it had a cobra hovering over the trees with the mist coming up. It was an awesome picture. I was like, “What’s the deal with that?” This guy was going through the process and he said, “Do you want this?” I said, “Yes.” I started the process. I didn’t even know that was possible. I went down to Fort Lewis, Washington. Started taking my flight aptitude test, my physicals and I made it.

You spent the early part of your Army career as a Warrant Officer flying. There was an itch to do more. There is a desire to serve the aviation community at an elite level. Can you talk about the persistence and the continued efforts that you had as a pilot in what we call the traditional Army? The opportunities that you saw, as there was the development of this time of this special operations aviation capability?

I was getting ready to graduate from flight school. You get your assignments 3 or 4 months before you graduate. I was getting checked out in the Black Hawk, which is a relatively new aircraft at the time. They were around but there were still Hueys around in that. I had orders to Germany to an assault company over there. I heard about this secret unit at Fort Campbell. I swapped with a guy. You could swap orders via the same aircraft type and stuff. This guy and I swapped. I went to Fort Campbell to the 101st. For the sole purpose of being in the same base as this unit that I had heard about. The 160th at the time didn’t wear patches. They didn’t have signs in front of their buildings. It was all hush-hush.

I flew medical evacuation for the 101st. I got there in early ‘86, maybe February or so. I immediately applied to the unit and they laughed me out because I was young. They only agree to assess and select experienced pilots but I kept going back. During that same time, I was a Warrant Officer. I didn’t understand the nuances of a Warrant Officer, which is that they’re very technically focused. They’re not normally going to command. There are some exceptions to that. Generally speaking, in the Army, your job is to fly helicopters. They have boat warrants. They have different types of warrants like intelligence and different types of stuff. Your job is in that particular field. You’re not going in command. You’re not going to do any of those things.

While I love flying and I still love flying, with my NCO background, I felt like I wanted more. I applied to Officer Candidate School and I made it barely under the wire. You had to be commissioned by the beginning of your tenth year. You had to be able to get ten years of commissioned service to be able to retire as a Commissioned Officer by twenty. It was an Army rule and it may have been the same in any other services. I had to apply right then so I applied. I was still short a couple because I’ve been going to college at night throughout. I had to give 60 hours at a time to go to OCS. I was a couple short so I had to do that simultaneously.

I got commissioned at 9 years, 10 months and 2 weeks. I barely just made it. October 16, 1987, which put me in the year group ’88 because I was after the first of the fiscal year. That’s when I got commissioned at OCS. I called the 160th when I graduated. I was on orders to the 82nd to fly for the 82nd Airborne Division, which is a great job coming out of flight school. I said, “I just graduated from OCS. I was one of the top grads. Would you consider and let me assess?” To my surprise, they said yes. They told me when I got there, “You don’t stand a chance. You’re not going to get picked up.”

Was it because you were too junior?

Yes, I was a Second Lieutenant. There was very few or none, really.

Second Lieutenant sits in the corner and just be quiet.

Since I was a former Warrant Officer, I had several 100 hours of flight time, which is why they agreed to look at me. I went through the process. I had to take an evaluation flight under night vision goggles and a physical fitness test. It was a whole series of things. You have a board of officers that you go through in front of. The guy who was walking in, the recruiting officer at the time said, “The deck’s stacked against you. They’re probably not going to take you.”

I went in there. I did okay and they took me. I had to spend my penance. I was supposed to go right to a flying company, but they made me go to the headquarters company, which was Collect for Combined Federal Campaign. Do all the things that lieutenants do, supply inventories, all of that stuff. I got there as a Second Lieutenant, that was February of ‘88. I stayed there pretty much through Lieutenant Colonel in the SOF community. I didn’t leave the SOF. I didn’t stay the whole time in the 160th. I did some other jobs, which I’m sure we’ll talk about.

Are you the first Second Lieutenant to ever be?

I don’t know that. Ultimately, there were three of us. JR Hunter was the other guy. He was there as a Warrant, went OCS and came back. He was a Little Bird gang guy. He got killed with Sonny Owens in Panama, Just Cause. There was another guy, Mike Slattery. He was a Chinook guy that came after me. Hunter was there before me. There could have been other ones. I don’t know. There was only a couple of us. We were not common.

I want to ask you a little bit more about the different levels of leadership that you’ve served at? It’s interesting because, in the military, they do a good job of separating what we call functional leaders, technical experts, and strategic thought leaders. You mentioned this in terms of the Warrant Officer as a technical expert. We could say that the enlisted ranks are functional leaders in roles. There are strategic thought leaders that become commissioned officers and general officers. I’m interested in your thoughts on this because you’ve served at each one of these levels. You’ve been put in this position where you’ve had to be each one of these.

The military does a great job of understanding that you need these different types of leaders and they’re comfortable putting them in these roles. The civilian world and the private sector are a little bit more difficult. They expect that people come in organizations, they have to be able to do a lot of different things. They’re not necessarily comfortable saying that this person is going to come here. Maybe they’re not a people person, but they’re a great coder or a great engineer. The only thing we want them to do is code and we’re comfortable with that. That may run its course in the private sector. Can you speak, and Mike as well, a little bit more about being comfortable having these different levels of expertise and allowing them to exist and live in these worlds?

In my particular case, I would describe it as a building block concept. I would say the first piece of leading is following. Learning to follow others. I made Corporal in the Marine Corps when I was in Okinawa, Japan on one of my tours in beautiful Camp Schwab up there. I was a direct leader, as a squad leader, as a corporal. I was promoted to Sergeant. I was a Staff Sergeant select when I got out. I hadn’t pinned yet. I was in the direct leadership mode. I could touch everybody and talk to everybody that was under my span of control.

As a Warrant Officer, I had a similar role. I was the Assistant Operations Officer for my company. I had some flight ops people. As a pilot in command, you command the aircraft. You’re in charge of that aircraft. It’s direct leadership. As a Commissioned Officer, initially still direct leadership, Second Lieutenant, First Lieutenant, a platoon leader thing. When you get up into the company-level leadership, you’re starting to build in layers of bureaucracy between you and that young troop that’s grind in a way. It becomes a norm.

As a Battalion Commander, then as a Regimental Commander, you have to evolve your leadership styles with that. You have to be able to communicate through multiple layers of bureaucracy. By the way, leadership is a learned skill. I don’t buy into the natural leader thing. I still learn. I’m still learning. You have to evolve your techniques. How do I effectively communicate as a Battalion Commander or Regimental Commander down to the lowest level troop? Going back to my beginnings, I didn’t shy away from making hard decisions and holding people accountable. I was also very cognizant of the perspective of a young soldier. That’s what we call in the Army a 10-Level, an E-1 through E-4 and how they view things.

You reviewed that.

Exactly. It influenced the way I communicated. I spent time investing in those young troops. I wanted to know what was going on. I routinely walked around the command and spent time with them, just so they knew how important they were to our success. Plus, I learned about problems in the command that I would have never known about through those interactions. That served me well. I was also active in leader development. I’ve always had a leadership development program from probably ’03 on up. As a Captain on up where I was committed to that. As a General Officer, it’s a whole other level because you’re a strategic communicator. It depends on the job but as a J-3 in my last assignment, I must have done three or four VTCs a day with the Joint Staff or with a geographic combatant command. I’m representing Special Operations Command to those. Words matter and your message matters. I continued to evolve my leadership and my communication styles based on that.

What was the evolution of moving from retirement to now leading a major nonprofit?

That was interesting. I took over from the very capable Vice Admiral, retired Joe McGuire, Navy SEAL. He remains a good friend of mine and I admire all the great stuff he did there. I’ll never forget, we were doing handover and he was leaving. I was sitting in his office, now my office. I knew about the foundation but I didn’t know much about it. I said, “How many people are in this foundation?” He said, “Sixteen.” I remember thinking to myself, “Sixteen? How hard could that be?” I’ve commanded thousands of people. It was hard because I wasn’t used to dealing with civilians. People think that in the military, you order people to do stuff and they do it. It doesn’t work like that. Especially in the SOF community, it doesn’t work like that.

What you do get with the military is a common ethos. There are more deferential leaders. When I was a J-3, I had Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines all working for me. You’ve got service cultures that are significantly different. You’re still military. You’re still united in a common cause. The civilian world was much different. Much more legalistic in some ways. Whenever you say, “As a leader, I’ve learned everything,” you’re missing the boat. I have learned after leaving the service that I had to continue to evolve on how I lead people and how I treat people. I’m not a screamer. I’ve never been a screamer. It’s still a different demographic, different culture. I’ve continued to learn and I am learning to this day.

Let me ask you about that factor of coming into a new organization because you’re right. It doesn’t matter what level you come in and how experienced you are. Going into a new organization is always going to create some semblance of the unknown. Some semblance of you coming in, especially when you’re going to be in charge, having to accept the fact that you may not know it all. As young officers, and you mentioned your time as a Second Lieutenant coming into the 160th where you have Warrant Officers who’ve been there for 15, 20 years. Their level of expertise is hands down the best in the world in flying aircraft. Now, you’re in charge of them. How do you come in that room on day one, week one, year one? As the Commissioned Officer-In-Charge who now looks around the room, what do you do?

[bctt tweet=”Change is ugly. Once you make the decision to change, you have to be patient.” username=””]

I’ve had discussions with young officers and all the services about that, whether it’s Green Berets, SEALS or Rangers because you’re not going to be the best. I would never say that I was the best pilot. I was probably among the weakest pilots in there because they’ve been doing it for years and years. They’re better at it. If you talk to a SEAL, a Ranger, a Green Beret platoon leader, they would tell you the same thing.

My team sergeant had been in the 10th group for twenty years when I got to the grid.

How are you relevant and how do you lead in that environment? The first thing is it is challenging but thousands have done it successfully. My personal opinion is you lead, you try to be humble, and you accept correction but you’re also prepared to make the hard call and take the hard right. I have seen it in even the most elite organizations that I served in, they still need leadership. They still need someone to be in charge. I’ve seen leaders make all the common mistakes. They try to be friends with everybody but that doesn’t work. Trying to make everybody happy certainly doesn’t work. Being consistent, exercising humility, not afraid to make the hard call may make you unpopular for a short time but over time, my experience has been that people respect you for doing that.

That’s what I tell them. You’re paid to lead. In my particular field as a pilot, I don’t care about you being a stick wiggler. What I want you to do is lead these guys. You enforce the standards of the organization. You make sure they do things in accordance with our SOPs. You are the enforcer of the standard and you lead by example both in your personal life and professional life. All that being said, you still make mistakes. I would tell you that I did and I do fail routinely. Most of the time I fail, I’m probably the only one that understands that I failed. I wish I would have handled that differently, said something different or made a different decision. You’re going to do that a lot, especially as a junior officer. The key is that you do an internal review of your actions and get incrementally better each time you do it.

That’s the demonstration of the humility that Mike talks about.

There are some things for the readers here and this is humbling for me to even sit in on this. I’d always known your reputation when I was on active duty. I’d never met or crossed paths with you. For an executive-level leader in the military with 41 years who says, “I’m still evolving as a leader,” that sends a point to all the readers that this process doesn’t stop until you’re six feet under. Anyone who tells you, you have leadership figured out, they’re full of you know what.

You talk about coming into the 160th. When I got to JSOC, I was an O-3. All of a sudden, what we call troop chiefs is an E-9. That’s scary. My first troop chief had twelve deployments under his belt, mine is three at that time. One of the things is showing deep respect for what they’ve done in viewing them as a sounding board for the decisions that you ultimately have to make. I don’t think there was a decision I made where I didn’t look at my troop chief and say, “What do you think we should do here?” It’s also building those relationships where they understand you’re there, that you’re a team player, that you’re not trying to seize power.

Sir, I agree with you. You can’t abdicate your duty to make hard decisions. This is where the SEAL community goes a little wrong. I don’t know if you knew this, you probably do. In a SEAL platoon, unlike the Marine Corps or the Army, which I was used to coming from the Marine Corps to the SEALS, they have three officers to their eighteen men. One O-3, a Navy Lieutenant, and usually two O-2s which are Lieutenant GAGs. I understand the intent was to get them to learn how to follow and also learn the tactical side of doing business. A lot of those young leaders are not platoon commanders, what we call the second and third O. They fall into a trap of trying to become popular and becoming one of the guys. It ruins the reputation of a lot of those young men and they can’t recover. Being an Infantry Platoon Commander, you have how many guys?

Forty-one.

One platoon sergeant and you were the only officers. It’s interesting how the structure is.

You say that and being a buddy and I will tell you that I fell into that trap. I was with my platoon, we were in Operation Prime Chance in the Persian Gulf. When I first got there, we did rotations over there operating off of barges in the late ’80s. We went to Operation Just Cause in Panama. I flew with the same guys. We ended up with flying missions in Desert Storm and over. You get too close and it clouds your judgment. I cherished those friendships. I’ve lost several of those guys. Several men in my platoon were killed in the Gothic Serpent in Mogadishu in ’93. I fell into that trap. I felt like I ultimately lacked objectivity.

Night Stalkers: When you lead, you try to be humble, accept corrections, and also be prepared to make the hard call.

There’s an argument to be made when you come into a new organization, that your most productive time is that first 3 to 6 months. One, your objective. It’s easier for you to call the ball like, “Mike’s not making it. He’s had a DUI. He’s done this. He’s done that. He’s not meeting the standards,” and to move them out. It’s much harder after you’ve been there a while. I say, “Mike’s had these personal issues. He didn’t get promoted. He’s this.” As a leader, you struggle with that. That’s why leadership is hard. It’s not physically hard. It’s not hard every day. If you want to be an effective and consistent leader, that’s hard. When I saw some, I make hard decisions, especially the more senior I got early on. Once I felt like I had enough of the facts to make some corrections on the way we were going as an organization, I didn’t hesitate.

Even though you came in as a Second Lieutenant, they put you in the staff job for a little bit. You still had a cool opportunity with an aircraft called the DAP. Talk a little bit about that.

In the 160th at that time, we had three aircraft types but 2 to 4 different missions. We had Chinooks and they cruised at an airspeed of about 120 knots. You had Blackhawks and they cruised at a similar speed, 120 knots at the time. Now, they’re a little slower and a little heavier. You had Little Birds. You had Assault Little Birds that had planks on the outside the people sat on and Attack Little Birds AH-6. They cruise at 80 knots. The AH-6 was the only armed aircraft we had at the time. What was happening was the Chinooks and the Blackhawks had to slow down significantly so the Little Birds could keep up. You’re negating. If you’re going 120, you go down to 80. You’re shaving off 30 of your airspeed for this support platform.

The decision was made by the command to modify a certain number of the Blackhawks more than a proof of principle to an armed variant. I just happened to be in the right place at the right time in D company, the Hooter Brothers. That’s where the DAP started. The DAP’s original name was Defensive Armed Penetrator. As an interesting story, General Schwarzkopf was a G-3 of the Army at the time. He is a three-star and they were still buying Apaches. The army was concerned that this aircraft would derail the Apache. The Congress would see that and say, “Why don’t you just do that?” The defensive was to say it’s defensive only. We later changed it to Direct Action Penetrator. They were given the task to stand up.

I volunteered to be the platoon leader. We had three aircraft. We didn’t have a great start. My platoon at the time, I had Cliff Walcott who was killed on October 3, 1993. I and several other guys were involved. We did a bunch of what we call OTE, Operational Test and Evaluation. Anyway, we stood up this platoon and then Just Cause happened right after that. We deployed to Just Cause. Cliff Walcott and I were flying together. We had one operational DAP. I somehow scrounge up a pallet of ammo because I knew the AH-6 guys would never give me any of their ammo.

What are brothers for? We’re in the fight. You’re out.

We had two 19-shot rocket pods, a 2.75 Folding-Fin Aerial Rockets. We had too many guns. That was the standard armament. Now it’s much different, Hellfires, 30-millimeter and whatever. I scrounged up this ammo. We came in on the last C5 into Panama before they are kicked off. I show up, Cliff and I were ready to shoot some. We’re fired up. We get down there. There were Apaches from the 82nd that wasn’t part of our task force but they were down there. Our Regimental Commander at the time said, “I don’t need you to do attack missions here. I need you to do assault.” They made us take off our rocket pods and I’ll never forget. I was crushed, “This is my big thing. This is never going to happen again. I’m down here in Panama.” Of course, the AH-6 guys weren’t going to pass up the opportunity to rub that in my face.

We were staying in hangar three on Howard Air Force Base. There were 1,000 of us in there. I was sitting there one night and these warrants walk up to me from BECO, the AH-6 company. They said, “Sir, LT. What does DAP stand for? Is that Didn’t Actually Participate or is it Didn’t Attack Panama?” They got a big kick out of that. I was slumped shoulder and was like, “Go away, jackasses.” From those humble and disappointing beginnings, we ended up with the primary mission to go after the Scuds being shot in Israel. The AH-6s were there but they didn’t have the legs.

We are going from Saudi Arabia up to Al-Qa’im if you’re familiar with geography over there. That was where they were shooting outside because they had to get close to get into Israel. We’d fly up there. It was testing our endurance of aircraft. We had to put auxiliary fuel tanks in there and everything else. We went up there and we were the only platform that can do it. It went well. That set the stage for future investment in weapons capabilities and things like that. The DAP was established after that. I moved out shortly after Desert Storm. My extended time as a platoon leader was finally over. That’s how it started.

It’s perfect timing.

It was. I went down to the Air Force and started flying as an exchange pilot in the Air Force.

How was that experience?

It was good. A friend of mine is retiring as a three-star and I was asked to write a vignette about him. I would say the tour at Hurlburt with Air Force Special Ops Command was one of the most formative in my career. It influenced how I approached my job as a Joint Officer for the rest of my life. To set the stage a little bit, there was the 20th Special Ops Squadron which was Pave Low and then there was the 160th. There was no love lost between those two. I’m being generous here, there was a lot of bad blood there. 160th has stood up and they’re developing capabilities for the Pave Low. They were the prime folks for that. There was a lot of friction or a lot of direct competition and it wasn’t healthy.

General Downing and then General Hall, he was Colonel Hall at the time said, “We got to fix this.” He did an exchange of prisoners thing. I went down there. Frankly, the friendships that I formed down there with Scott Howell, the JSOC Commander, Jim Slife, the AFSOC Commander, Greg Lengyel just retired, Air Force two-star and many others. I learned their culture which is significantly different from Army Aviation culture. It wasn’t bad. It was just different. Once I understood it, it influenced me as an officer. It certainly made me a better Joint Officer. I’m grateful for that too.

I snagged a wife out of the deal too. My wife was my Squadron Intelligence Officer. I’m blessed to have her. She raised my kids. She’s just awesome and remains so. She’s the best thing that ever happened to me. I was there from ‘92 to ‘96. I was an instructor pilot down there. I flew a lot. I made friends and it helped me be a more effective officer and a better team player. There’s a team player with your peers but also in a broader context, a team player across the enterprise. I’m very grateful for that time there.

That’s an interesting point too because there are many times you talked about the conflict between departments. When you look at companies and there’s always this internal politics. We talked about it all the time. The company of these people doesn’t like them, and they’re trying to take what they think is their part of the work. It can create a toxic environment. A lot of leaders are not willing to stand up and say, “You two don’t like each other that much. Here’s how we’re going to solve this. Sit in a room and start working together. Tell each other why you don’t like each other.” You can go far by doing that.

You could have a physical altercation.

Sometimes it results in good relationships.

Sometimes you just got to get that out there. I’m not recommending that in the civilian world. You will pop on each other. It’s probably frowned upon. I agree. When you become an organization and you see a need to change that organization or make a significant change or you have a mandate. That came into play when I was the 160th Commander. When I was the 160th Commander, I commanded an O-6 level organization. I was part of the US Army Special Ops Command, USASOC. On procurement dollars, the Army has different bins of money. All the services do procurement, operations and maintenance, research and development. All different pots of money. For operations and maintenance operating funds, the 160th accounted for 50% of the US Army Special Operations Command budget. On procurement and research and development at the time, the number was up to 70%.

These are significant numbers?

Yes, this is not chump change. This is a lot of money. I’m an O-6 commander who has a warfighting mission as a Colonel. Not only do I have a tactical operational responsibility, which is global. When I was there, I had people in Afghanistan and Iraq. We were routinely around the world. My organization was spread across the country. I had a battalion in Fort Lewis, Washington. I had one in Savannah, Georgia. My headquarters is in Fort Bragg. I was in Fort Campbell. I had to manage these programs and this budget, state requirements and defend my funding. It was too much.

The battalion commanders did the tactical stuff. I monitored it and tried to make sure they were resourced. Where a traditional Colonel level commander in any service, what I would call a down and in warfighter, I was exactly the opposite. At the end of that, I said, “We’ve got to have a resourcing headquarters above us.” I didn’t need another operational headquarters above us but I did need someone to take in the military called Title 10. The training, fielding equipment, manning, all of that stuff were off my plate. Defend the budget, build new capabilities to make sure that we maintain. To use Admiral McRaven’s phrase, “A comparative advantage over our adversaries in the future.” It was too much for a Colonel to do. I didn’t have the staff for it.

We stood up the Army Special Ops Aviation Command. There was a very good partner of mine, Steve Mathias who long since retired and works for Bell now. He was instrumental from the headquarter side and he was my partner in crime. We got to push through where we got this one-star headquarters stood up and it was what we needed. I will tell you, first of all, you got to be thoughtful with change. Make sure you’re not solving the wrong problem. Two, once you decide to change, you have to be patient because change is ugly at first. I used to make the joke and I go to my battalion commanders and I said, “The span of control is too much for me.” Everybody was like, “Yes, sir. You got to trim down the span of control.”

I got replaced by a Regimental commander. It was funny. Everybody was all in on reducing the span of control until they figured out that you control less stuff when you take away the span of control. Where they could influence things, now they can’t. Now that general officer headquarters says a response. There was a lot of pushback. You’re moving people’s cheese and you’re changing stuff. You’ve got to be patient for that middle part. Now, it’s a new normal. There is a generation of 160th folks and that command has always been there. The command is developed and matured over time and is more value-added. When you implement the change, be thoughtful, be patient because it’s going to be ugly. At first, it’s going to be screwed up. Eventually, you’ll get to that. It’s not an end state but you get to a point where your value-added. I learned a lot through that process about change and being an agent of change. Landmines are out there so you got to be careful of that, but also taking the long view on change.

One of the biggest components of change is often the development of a mission or a set of values. The 160th has a motto, “Night Stalkers don’t quit.” How do that motto, that mission and those values drive the organization? How does it bond the elite performance of the operators in that organization? How does it make sure that everybody who comes to work every day is there for the same reason?

[bctt tweet=”There’s a difference between culpability and accountability.” username=””]

First of all, you have to be a standards-based organization or learning organization. Enforcing standards means that sometimes you got to let people go which is painful. That’s what I talked about getting close to your platoon. Over time, you got to get rid of that guy or gal or whatever. “Night Stalkers don’t quit,” that motto was in place long before I got there. I would say the culture of the 160th is very unique. In Army Aviation in general, they only exist for one reason. That is to support that soldier on the ground. For the 160th, it’s that SEAL, that Marine Raider, that Green Beret, that Ranger or that Special Tactics Squadron on the ground. That’s the only reason we exist.

We have a strong and intense focus on supporting that Ground Force Commander. I will tell you that I took that probably to the extreme. I tell them, “If we put you in, you can bank on it. We’re going to come and get you. I don’t care what it takes.” Look at what happened in Mogadishu. We lost a lot of aircraft. We lost a lot of people. There were some aircraft that we lost. Super Six Four, Mike Durant’s bird, Cliff Walcott, Donovan Briley, Super Six One were shut down. We had a bird infiltrating Special Tactics Squadron that took an RPG. That one limped back to the base and was done.

We had another one hit with an RPG and cuts a guy and operator’s leg off, Brad Halling, a retired Sergeant Major. We lost a bucket load of airplanes that day but we never wavered. We never left them. We always went back anyway. We had Little Birds landing in the street pulling out wounded guys. That defines us and with that unwavering focus on supporting the commander on the ground. When I say commander, I don’t care if that commander’s an E-6, a Staff Sergeant or a Colonel. If he’s the guy that I’m responsible for supporting, I’m going to do whatever it takes to support that unit.

We’ve seen it in action. We knew it in that lens to the reputation that generations had built. The TF 160th. I have never been more impressed. What impressed me the most was the professionalism. The professionalism of the 160th was never in question. I know that represented that you held yourself with a lot of pride. You talk about standards. Often, companies won’t get rid of people because they have tenure. I believe trust or loyalty is a two-way street. Just because you tenure, once you stop serving the organization, it’s time to go. What was it like switching from conventional aviation to the TF 160th? Those new pilots, whether they’re warrants or young officers, how quickly do they have to ramp up to the bar?

Initially, when I got there, there’s a term Green Team out there. We call them the Green Platoon. Now it’s a Special Ops Aviation Training Battalion. That training pipeline is very long. What they produce at the end on the pilot side is a copilot. The learning begins. When you come into the Special Ops world, you go no matter what. I’m familiar with the 160th but it’s the same in any of the other components that are out there. You’re operating in a lower level than that organization when you come in there. It’s up to you to come up to that organization’s standards or you’re walking. You’re going to be shown the door.

When you come in as a co-pilot, we gave a guy or a gal now two years to make a fully mission-qualified pilot. It wasn’t a hard rule but that’s when we started looking at them like, “Are you progressing? Do you have a future here?” If they didn’t make it, we’d move them on. We give them opportunities to succeed, additional training, additional flight hours, things like that. We weeded out a lot of those folks in our assessment selection process. What we were looking at, are they trainable? We didn’t expect them to meet our standards. The assessment was, do they have the potential to meet the training? That process continues to get refined and better. The SOF community in general has gotten much better at that. That put us to the right folks. We were largely successful. Not 100% and I would be skeptical and suspicious if we were, but we do produce a pretty good product there. Most people rise to the occasion.

Let’s talk about that standard because there’s a phrase that you use in the 160th. It’s plus or minus 30 seconds. To the average person, you look at that standard and you think, “You just fly the aircraft. You have to be there.” It’s a mentality. In terms of time, if you were to look at the most tactical level. Plus or minus 30 seconds means the time in which you’re going to land that aircraft and be on the target. When you think about precision standard, that is a near-impossible standard to maintain. Yet it is the minimum baseline standard for the 160th as an organization.

It is and we still evaluate pilots to that standard to this day as far as I know. I’m sure we do. I would be shocked if that standard had changed. I took my FMQ check ride, Fully Mission Qualified check ride. They take your navigation systems from you and so I had a compass, a clock and a map. I’m looking at smokestacks to see other smoke coming out to see where the winds are coming so I can crab into the wind and terrain association or navigating. It’s different now. Now, you’ve got a digital map and multiple GPS.

Clay in Little Bird

It’s interesting when you still start your training in the 160th as a pilot, your first several hours are in a Little Bird. You’re not even rated in it. You’re just navigating and you have a compass, a clock and a map. It’s the foundation of the organization. It sets the standard. It’s not as impossible as you may think. Our planning is developed to the point where it’s the reverse planning sequence where we know when we got to take off. Do we need the standard every single night everywhere? Absolutely not. It does set that culture of excellence and organization of standards. That is one of our fundamental standards.

A unit like the 160th is a finite resource. There are limited aircraft. There’s limited personnel that is trained to the proficiency level to execute these missions. Before 9/11, Special Operations Forces were used as projections of power in a short duration. A few days, a couple of weeks, maybe a month or two at a time. They then came home and went through the training cycle. You spoke a bit about training and historically, you train 80%, 90% of the time. You execute that operation 10% or at most 20% of the time.

Even less than that probably if we’re talking operational stuff.

Post 9/11, we’ve been in conflict for twenty years. That takes a toll on an organization. How do you manage to sustain operations at a high operational tempo? This endless need to perform at a peak level across people, process and technology in a mission that I would classify as no fail. We’ve spoken previously in other episodes with other people. We spoke with Dr. Claudius Conrad who leads the medical field in minimally invasive pancreatic robotic surgery, and this is a zero fail, not even a centimeter and millimeter. It has an effect on a patient’s life. In your world, it is a no-fail mission for the people on the ground. How do you keep that level of readiness?

Post 9/11, it flipped that dynamic on its head. Right now, we struggled to train at all. It changed the SOF community and the military forever. On the plus side, the 160th and certainly the other SOF units are more tactically proficient in their mission and have more experience in a myriad of environments. I’ve flown in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere. Iraq and Afghanistan are two completely different environments, with different threats and challenges. On the plus side, we’re more proficient. Now we have more combat experience than we’ve ever had.

The biggest challenge that I saw was we had a requirement to maintain proficiency in a lot of different tasks because we were subject to no-notice deployments worldwide. For instance, staying current on landing on ships and doing maritime-type operations. You’re not going to do any maritime-type operations in Iraq or Afghanistan, I can tell you that. We squeeze that in when they’re back in the States. The biggest issue that I had on readiness was chronic fatigue. You started seeing units cut corners at things and that’s where that leadership thing comes in. We’re standards-based. If you see them doing that, on one level, it’s understandable that they’re doing this based on fatigue but it’s unacceptable, regardless. You have to enforce the standard.

I had that. I was confronted with that early on in my command tour. Readiness becomes both on an aircraft. When the aircraft’s shot up all the time, we had to do a lot of repairs, riding them hard. It’s a challenge but that’s what leaders are paid for and it was my job. General McChrystal was demanding on aviation because we’re a high-demand low-density asset. He wanted as much as I could give them. I joke with him after, and I have great respect for him and Admiral McRaven, for that matter. They’re two of the finest officers that I worked for. I used to tell him, “Sir, my job is to meet your operational requirements but not break my unit in the process. I’ve got to balance that.” I was able to do it and maintain an acceptable level of readiness.

Mike talks a lot about what happens when you fail. What happens in these environments when you don’t meet the standard? Do you have an example of when that’s happened and how you responded to it?

Yes. I was confronted with a failure to meet the standard. It wasn’t a flying thing necessarily. It was but it wasn’t what you would expect. It wasn’t like we didn’t hit a target properly. That happens, certainly where we screwed up and there’s no doubt about it, and it will happen again. I had taken command of First of the 160th Battalion. I’ve been in command for about a week. We had flown one of our aircraft to a sister Battalion, Third of the 160th down in Savannah for a major overhaul. We call it a phase inspection. The crew flew the aircraft down there and dropped it off.

They had an empty phase bay in the hangar so they were going to do the maintenance on it. The first thing they do is they crawl all over it and do an inspection and write up everything that doesn’t work so they can fix all that stuff. They were crawling underneath the aircraft and the aircraft had huge holes in the bottom of it. When I say huge, I don’t know how big they were, but they were not pinholes. They were big holes. We had these holes and I was disturbed by that because we do pre-flights every flight. We do daily, weekly, monthly maintenance inspections on the aircraft. I was concerned. How could this have happened? When I asked, nobody knew how it happened.

I conducted an informal commander’s inquiry. I sent over an officer to walk around the hangar, question people and figure out what was going on over in that company. The officer came back and said, “They’re not performing pre-flights. They’re not doing their daily maintenance.” Keep in mind, this was that thing where I said understandable but it’s not acceptable. They were in combat all the time. They were back and forth in this organization. In my opinion and experience, there was a lack of leadership on maintaining standards there. They weren’t doing those things. They weren’t doing those blocks and tackle things that you have to do right like clean your gun, make sure your kits are good, make sure your aircraft’s pre-flighted and those things. I wasn’t happy, I’ll put it that way.

I called in every leader of that company, Commissioned, Warrant Officers, and Non-Commissioned Officers. I had to get permission from my boss to handle it at my level. He was gracious and did that. I gave each one of them a letter of reprimand. I called them in, read the letter to them and with that, “Do you want to work here?” I was authorized to fire anybody. No one at that time said they didn’t want to work here. Now, I look back on that and I enforced the standard. I look at that now as an opportunity.

I was concerned coming in that we were suffering from chronic fatigue and that we were going to have an accident. The wheels were going to come off of the vehicle there or our unit. This allowed me to send a message not only to that company but across the whole formation, “We have standards. You’re going to meet those standards or you’re not going to work here.” I saw that as an opportunity, not one that I created but was presented to me. Overall, it had a positive impact on the unit. It went through that unit like wildfire. They knew there is a new sheriff in town and he is not playing. To me, it’s hard to prove a negative but people tightened up their shock groups because they knew I wasn’t going to tolerate it.

When I gave them letters of reprimand, in the Army we have a thing called the local file. As long as they didn’t do anything else, that thing didn’t follow them. It wasn’t a career-ender. In that organization where you have those egos and those high performers being told that you’re screwed up is punishment in and of itself. I got everybody’s attention. That was another one of those formative experiences where I learned. This was an opportunity to keep the ship going in the right direction.

I’m always looking for opportunities when it comes to leadership. Sometimes, I want to fly off the handle and hold somebody accountable. I’m reminding myself, “This is an opportunity. How you handle this is going to impact this young leader.” What was the corollary to not holding them accountable? You guys could have potentially lost lives.

You’ll hear the safety guys tell you that an accident isn’t one event. It’s a series of events. It’s linked in a chain that ends up cascading. We broke that cycle. We took one of the links out of the chain. They’re a high performing company. In fact, one of the officers that I gave a letter of reprimand to became the regimental commander.

[bctt tweet=”Humans are more important than hardware, so you assess and select the right people.” username=””]

Did he bring it up with you?

We haven’t even brought it up. I knew him from before and he’s an exceptional officer. I’ve always thought highly of him and I was his biggest cheerleader to take the regiment. They go through a special selection process for that command. I know it hurt his feelings. I’m raining on his parade here. I’ve never spoken to him about it but I would and I should. I’d say, “Now look in the rearview mirror.” It was the right thing to do.

Prior to the show, we were talking about one of my former commanders that you knew. He led intrusively. At first, I thought it was micromanagement. There was a maturity issue with me until a good master chief said, “He’s being intrusive because he cares.” He was holding me accountable. To this day, I go back to him and I thank him for what could have been viewed as an unpopular decision to hold me accountable. I thank him for what he did because it formed me into the leader that I am. There’s a lot of evolution there. You made a decision. Let’s be honest here, a lot of leaders wouldn’t make that decision because they don’t want to be unpopular within the first week of taking command. That’s out of fear. I get the psychological fear of being unpopular and losing credibility early on. I’m assuming it was a 2 to 3-year tour?

Two years and then I ended up picking up my box and my I Love Me stuff, moving down, and taking the regiment. It was toe to heel.

You maintained the standard across the entire organization. A lot of leaders will find it easier to come down on more junior folks and they’ll look at more senior folks. They’ll give them the slap on the wrist and say, “You shouldn’t have allowed that to happen.” You looked at the whole organization and said, “Every single person is accountable here.” We think about this in terms of responsibility and accountability. The responsibility for that aircraft and maintenance was delegated down. The accountability for that aircraft and the performance of everybody involved goes all the way up to the most senior person. That’s how you viewed it.

There’s a difference between culpability and accountability. Culpability is who’s directly responsible for not doing that pre-flight or that daily maintenance specs on that aircraft, but the whole chain of command is accountable for that. I’m accountable for that ultimately for the 160th or for that battalion.

Had there been an accident, it would have been you.

At some level, I’m still accountable for that. I’ve just gotten there so I was in the honeymoon phase. You hold people accountable. If you don’t, you’re doing the organization and that individual a disservice.

The 160th is not only one of our most advanced combat forces, but it’s also a critical component of our history. It’s been involved in so many different operations. You’ve brought up a lot of them here, a lot that we define as successes and some we define as failures. We can look at it and say it was both in different aspects. Grenada, Panama, the Persian Gulf, Iraq, Afghanistan, operations in Central and South America, Somalia, which you’ve brought up a couple of times, and a lot of operations that we’ll never know about. You know about them. Mike and I don’t know about them and no one else ever should or will.

Probably in the Battle of Mogadishu and Somalia ‘93 was where the 160th has gained its notoriety. Cliff Wolcott and four others in the 160th were killed. Mike Durant was taken captive. You’ve spoken about the risks that are involved in these types of operations like crashes, hard landings and the toll that it takes on the equipment and the personnel. You also noted when we spoke about it in terms of the Warrant Officer piece. The longevity of the personnel in the unit, their experience in both success and failure and their effective intelligence that comes from being there and doing over and over again at this level. Their ability to perform over and over again, push the envelope, push the limits of the aircraft, push the limit of the personnel allow you as the leader and as the commander to assume more risk. Can you talk about, when you sit at the lead of an organization and you have confidence in that personnel under you, the equipment, their experience, and how they operate, how you can assume more risk?

It comes down to assessment selection and talent management. One of the most important soft truths in my opinion is that humans are more important than hardware. You assess and select the right people. You’re a standards-based organization. We have a strong standard operating procedure and we call it the TACSOP. Everyone’s expected to comply with that and follow those procedures. If you’re not, after the flight, you’re going to hear about it. We have this culture of excellence that’s established there. It’s a self-policing culture.

I’ll never forget I was over in Baghdad in ‘03. It was a funny story. I’m sitting there in the jock in the morning. We work at night so I’d woken up at 1:00 or 2:00 and I’m sitting on my laptop in the Joint Operations Center. I’m surfing my email with a cup of coffee in my PT gear. The commanding general of the task force was sitting at the head of the table and his phone rang. He picks it up and he’s like, “Uh-huh.” He looks over me and goes, “Clay, I got a report that two of your Little Birds shot at the base of this tower out in the middle of nowhere.” It was funny, I said, “Sir, I’ll check. I would be shocked if that were us. Our discipline is better than that.”

I go in there and I sleep. This 1:00 or 2:00 PM and I wake up. This platoon leader who I think highly of and he’s a colonel now, I said, “Did you guys shoot something yesterday that you weren’t supposed to shoot?” He said, “Let me check, sir.” He was incredulous. That couldn’t have happened. I’ll never forget, he came back to me and he said, “No, sir. It wasn’t us.” There are other Army aircraft that could be confused as a Little Bird over there, so that was plausible to me. I go back into the one-star Air Force general and I said, “Sir, it wasn’t us.” In the back of my brain, I’m like, “I hope that’s true.” He picks up the phone and calls back to the three-star headquarters to say, “It wasn’t us.”

I’m not kidding you. Five minutes later, this captain comes walking in and he said, “Sir, can I have a word with you?” I walk out with him and under my breath, I said, “If you’re about to tell me that you shot that tower, you’re going to have a bad day.” He said, “Sir, Mr. X would like to amend his previous statement.” That’s how he said it. I was like, “You rat.” I went back in and did the mea culpa. I told my boss it was us. Here’s the thing that impressed me about that particular company. Something had to be done. This was a breach of flight discipline and he clearly violated the standards. The unit immediately took action. They called back to their commander who wasn’t forward with us at the time. We were on a rotational basis. They pulled his flight. This was a flight lead, which is our highest level of qualification. Once you’re in the unit, it takes 6 or 8 years to make that.

They pulled that from him and policed him up. They enforced their own standards. I was going to do it anyway but they did it. To me, that’s a learning organization. That policing and enforcement of standards isn’t just me at the top, but it’s all through the depth and breadth of your organization. That was a clear example to me of them maintaining their own standard and having pride in their own organization. They took care of it. You take more risk because they’re going to police each other up. Our Warrant Officers stay there for years.

The example I use is Warrant Officer Karl Maier who is a good friend of mine. We went through Green Platoon together back in ‘88. He got to the unit in ‘88 and he was flying Little Bird, what we call Slicks. It’s assault Little Birds. He was the same guy that landed in that intersection in ‘93 in Mogadishu and picked up the two wounded operators. He retired a few years ago flying the same missions over and over again. From ‘88 to maybe 2018, think about that. That’s a long time. It’s not cavalier about the risk. It’s that you’re a standards-based organization and you train to a high standard. You hold yourselves accountable to a high standard, and then in combat, you empower those individuals to make decisions.

They’re the frontline tactical commanders that are making on-the-spot decisions with the concurrence of their air mission commanders, but the flight leads in our organization are empowered to do that. Part of that is accepting more risk. I’m not saying that you don’t hold them accountable for making mistakes, but that you’re behind them. I’ll give you an example. I was over in Iraq. I feel like I spent half of my life over there. Our standard duty day is sixteen hours or something like that, which is long. We had been on a mission up near Mosul somewhere and north of us was Balad Airbase. The ground force went long on a target and I had to extend them to 18 or 20 hours, which is a long time.

They did the ground forces exfiltration. They were taxiing to get some gas before they came back. One of the aircraft clipped the corner of a hangar with its rotor blade when he was turning and misjudged it. I’ll never forget, the safety guys came to me and they said, “Sir, that was an accident.” I said, “We’re going to investigate it. We’re going to do all that.” To be clear, I own that. I extended that crew and if you extend that crew beyond their duty day, that’s my accident. We’ll do the safety stuff. We’re going to look at it and make sure we learn from it. As far as accountability, that resides with me. I’m the one who pushed them beyond what is considered safe and normal because that’s what the ground force commander needed. At the end of the day, when something went wrong, I own that.

I almost want to say it’s like a moment that you know you’ve arrived. When a problem within your organization happens, then your subordinate leaders start moving right away to fix it. They come to you and say, “Sir, this is what happened. Here are the facts and here’s what we’re going to do about it.” The one thing for the readers is these after-action reviews, which some people call debriefs or hotwashes. What’s unique about these organizations is people will call each other out. I’ve seen some of them get heated because these after-actions are happening after a long day of training or mission. What’s unique is that there’s this vulnerability in these cultures. Even though two people may call each other out in a hotwash, you’ll see them five minutes later coming to one another saying, “You’re absolutely right. I screwed up. Here’s what I’m going to do about it.”

The best organizations are the ones that are brutal in those hotwashes debriefs, after-action reviews. Frankly, in my organization, the Little Bird gun company and B company was absolutely brutal on each other. I used to joke with them and say, “You are proof that poor parenting still exists on Earth.” They would have their Tactical SOPs open. If your products on the wall, charts, maps and everything wasn’t in accordance with that standard or you did something not in accordance with the standard, they were brutal. Now, you’ve got that nirvana. When you said the organization’s coming in, you’re absolutely right. You still need leadership. When it’s in depth and breadth, you’ve got a learning organization that holds itself to a values-based and standards-based organization.

Everyone needs a tune-up. I need the realignment. I’ll hold the standard and life happens and I get out of balance. I’ve got great leaders that come in and realign me which I need from time to time. What I see in the private sector, and this sounds overly simplistic, is that few of them engage in the after-action review process.

It’s easy. You’re tired, especially if the op went well but I’ve never been on a perfect op. There are always mistakes. I always pay attention if they go through the hotwash. There were companies of mine that went through the motions. It’s 3:00 AM and you’ve been flying for 6 to 8 hours. We fly without doors when we’re shooting a lot and you’re freezing, cold, tired and want to go home. The organizations that go through that and they’re disciplined about that. In my experience, those are the most high-performing organizations, but a lot of units don’t do that well.

In the sales world, they would call it post-mortems, which imply that something went wrong.

I’ve learned more as a person, father, husband and soldier in hearing things that I wanted to hear the least. I learned more from when I screwed up. There were impacts and consequences that I learned from when things went right. I definitely learned, “That works. That’s a good thing,” but I learned much more when something was brought to my attention. I’m thankful for leaders, both noncommissioned officers and officers, especially when they’re subordinates and they had the moral courage to come to me and say, “Sir, you screwed that up.” That’s hard to find and you got to reinforce it all. I had a standing commander’s intent kind of thing. One of them was I value soldiers with moral courage because I will never knowingly do anything to hurt this organization, but I may do something unknowingly and you need to bring it to my attention. You can’t just put it on a sheet of paper. You got to reinforce it in how you conduct yourself every day.

[bctt tweet=”The best organizations are the ones that are brutal in those hot washes, debriefs after action, and reviews.” username=””]

Let’s talk about the ultimate responsibility that we have to others who’ve served in the Special Operations units. I want to talk about Special Operations Warrior Foundation in that respect and your role as the President and CEO. The goal of this organization is to empower the families of our fallen and severely wounded Special Operations warriors and children of all Medal of Honor recipients. This is a mission that’s close to my heart and to Mike’s heart. What we’re doing here with the show and the Talent War Group, we talk about it in our open and we talk about it in our close. It’s an organization and your efforts are important to us. It is where we came from. It’s what gives us the ability to be who we are now. It’s important that we give back to this organization as we build these programs. Can you talk about the Special Operations Warrior Foundation, your role and what the organization is doing?

The Special Ops Warrior Foundation is over 41 years old. We had our 41st anniversary on April 24, 2021. It was created in the aftermath of the failed rescue attempt for 52 American hostages held in Tehran that costs the life of 8 Americans, 3 Marines and 5 airmen. Two aircraft collided on the ground at a desert refueling spot known now as Desert One. They left behind seventeen kids. That task force that was charged with that hostage rescue. The leaders made a commitment to pass the hat and fund the education for those seventeen kids. That’s how the organization started.

Over the years, our mission has grown to now where we provide for education. We call it Cradle to Career of children of fallen special operations personnel and the Children of all Medal of Honor recipients, living and deceased. We also provide immediate financial assistance to severely wounded, ill or injured Special Ops personnel. Severely is defined as being an in-patient in the hospital. Not stitches and back out on the line but something that put some costs on a family. It’s very unique. People think that it’s a college scholarship organization and that is certainly a big part of what we do, but it doesn’t even begin to describe what the organization does in total.

We have a very unique approach that’s born over the years of watching these families and that is the long view. We invest in these kids starting in preschool. We pay for preschool up to $8,000 per year per child. Why? Preschool has been shown statistically to give kids a leg up and dramatically increases their chances of a successful post-secondary education. It’s about reading. We provide unlimited tutoring from preschool all the way through college graduation. That includes SAT prep, ACT prep and all of that. We have mentoring programs that start in the eighth grade with kids to lay out what their dreams are and then a path to get there and continue through college.

We pay for their college visits. We run a college prep course every year in Tampa where we bring the kids. We teach them financial management, study skills and time management. We have folks teach them about writing their essays for their applications into college, how to choose a major and what you should think about. Here’s a cool thing, the mentors for these kids that are about 25 to 30 every year are kids that have lost a parent and they are graduates of our program that come in. They live in the dorms with them, so they’ve got that shared experience.

We pay for their college visits, study abroad and internships. We provide them with a stipend because internships, more often than not, lead to a job or a career. We don’t want them not to go because they can’t afford to relocate somewhere. We give them a stipend to get them settled there. We pay for their college. We don’t ask them to go to any other charities. If they choose to go to a technical field to be trained as a plumber or a hairstylist, that’s fine. Our country needs those. If they go to an Ivy and they’re in Harvard, we’re going to fund it no matter what.

We reach out to them proactively within 60 days of the death of their loved one or when they receive the award. It is not even an application. It’s a contact sheet. They never fill out another application for us. We proactively reach out to them and they’re in. I had four kids in college. Believe me, I filled out a lot of scholarship applications every year. We help place them in a career and we have a good program that’s getting better and better. We also have a special needs program to take care of our special needs kids. We have about somewhere between 25 and 30 with varying degrees of challenge. We’re committed to funding their education as we would get in a traditional pipeline.

Here’s the result, that Cradle to Career, that long view, there’s preschool, tutoring and post-secondary education. In 2020, we had 42 kids graduate high school and 38 went straight into college, 2 joined the military and 1 took a year off. We had 93% of our kids graduate college on time. Both of those statistics are well above the national average, somewhere between 20% and 30%. Keep in mind, these are kids that have lost a parent. Most of them are in single-parent homes. It’s clearly high risk. That validates this long view and this Cradle to Career approach we take. It makes our country better and it honors our commitment to those that have made the ultimate sacrifice for our country or performed an act of valor, which every one of our Medal of Honor recipients is not special operators. They’re all included in our program and they were special that day.

To me, we should do no less. If something happened to me, that’s what I wouldn’t want, for someone to take care of my kids. I wasn’t on the hunt for a nonprofit. It wasn’t even on my radar. To me, having served a life of service for 41 years from 17 years old to 58 when I got out, and to have this opportunity to continue to serve the community, I’m extremely grateful for. We talked about Cliff Wolcott getting killed in Somalia. Cliff’s widow, Chris and his son, Robert, it’s personal to me and there are many more. My middle son is Mitchell Wolcott Hutmacher. He’s named after Cliff. Our whole staff is committed like that to our families. It’s a great organization. We’re transparent. We’ve had the highest rating on Charity Navigator. You can get a four-star rating for fifteen years. In 2020, our overhead was below 5%. We’re committed to good stewardship of the resources we’re provided and our mission is extremely impactful on these families and we should do no less.

We all know that our personal communities have foundations like the SEAL Foundation and the Green Beret Foundation, and they’re doing good work. Many people gravitate towards the Special Operations Warrior Foundation because of the purpose of the kids of the fallen, you can’t find a higher calling than what you’re doing. To serve your country for 41 years, thank you for your continued service to all of us. Where can we donate?

Go to SpecialOps.org. There’s a button there to give and also, all of our documents are there. You can look at all our financials posted there. The details of all of our programs are posted there. We have the spinner, which gives you up to the date. There are over 990 kids and we’re over 400 college graduates now. It’s all there. It’s what we exist for and I have no desire to do anything else.

Special Operations Warrior Foundation Donation

As we close out, we ask every guest on the show about the three things that they do every day to be successful. We talked about the Jedburghs back in World War II. We say that the Jedburghs had to do three things to be successful every single day They were the foundational elements of their mission. They had to shoot, move and communicate. If they did those three things every single day with precision, it didn’t matter what challenges came their way. They would be able to focus on those things and find a resolution. What are the three things that you do every day to be successful in your world?

I start my day off with a prayer every day. I do PT every day and I spend time with my wife when I’m home every day. I know a lot of Special Ops guys, Mike does and you do as well. They’re great operators, but their personal life is in shambles. I invest in myself and my family every day. It’s a prayer every day. It’s that physical fitness piece and it’s been quality time with my wife. She tells me, “Go off and play Captain America. I’ll take care of the kids.” She was an Air Force officer. I mentioned that I met her down at Air Force Special Ops. She gave up a promising career to take care of our kids. It was her call and that’s a hard call to make. I don’t know that I would have done it. My children would have paid the price for my lack of moral courage there.

Elite performance, as we define it on the show, comes down to nine characteristics. They’re defined by drive, resiliency, humility, adaptability, curiosity, effective intelligence, emotional strength, team ability and integrity. We say that all people who operate at an elite level demonstrate these nine and they rarely demonstrate them all at the same time. It’s a combination of different ones at different times that make them who they are depending on the situation. I like to assign one of these, even though I caveat that you have all of them. If I were to tell you that you had one, I’m going to tell you that you live by effective intelligence.

I want to quantify that because you’re a General Officer with 41 years in the military. The Army removes the branch insignia of a soldier when they reach the level of a General Officer because that is the Army now designating that person that they are capable of not being a specialist anymore, but taking their time in the military, the totality of their experiences, they’re applying that experience and their knowledge to the situation at hand. They’re using that effective intelligence to now lead their organization and transform their organization for the better every single day. I thank you for joining us on the show. This has been truly an amazing conversation. We are in debt to you, everyone who’s worked with you, and the organizations that you have served for decades.

Thanks for having me on. I’ve enjoyed it. I’m the one who’s grateful for the opportunity to serve in uniform. I got more out of the service than they got out of me. The Special Ops Warrior Foundation is the same case. I get more out of helping these families than they probably get out of us, at least on that personal satisfaction level.

—