Professional football requires its players to be fast, strong, and smart. It’s a sport, but it’s also a $16B business where results are the only thing that matters.

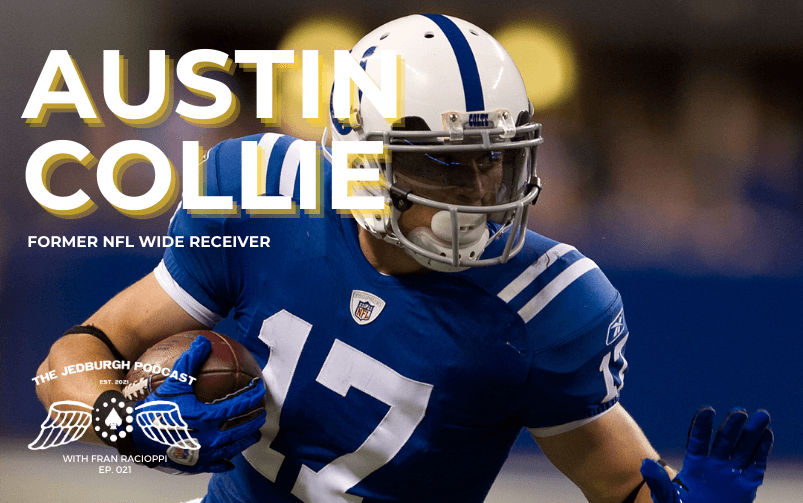

Austin Collie played wide receiver for the Indianapolis Colts and the New England Patriots. He was drafted in the 4th Round of the 2009 draft andis a member of the Brigham Young University Hall of Fame.

Austin joins host Fran Racioppi to discuss how our drive for perfection is based on competition, the identification of our faults, and the need to correct those faults quickly, without compromise and without delay – or risk having our weakness exploited.

Austin and Fran break down the importance of chemistry on a team and how the greatest of all time demonstrate personal accountability and responsibility to their team before themselves. We also discuss the series of devastating concussions and injuries that slowly forced the end of his playing career. He explains the difficulty we face in accepting the end, but also how we can embrace new opportunities if we bring the same level of passion, dedication and drive to our new endeavors.

An NFL wide receiver turned technology start-up executive in Remote Process Automation at JOLT Advantage Group, Austin proves that we are the only ones who can control how hard we work. He is the definition of our core tenets… “hire for character, train for skill.”

—

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

Austin Collie is a former NFL wide receiver. He was drafted by the Indianapolis Colts in the fourth round (127th overall) in the 2009 NFL Draft and later played for the New England Patriots. He played college football for the Brigham Young University Cougars where he set and holds BYU records for career receiving yards and career touchdowns. He is second on the list for career receptions. In 2008 he led the NCAA in receiving yards per game, total yards and consecutive 100-yard receiving games at 11.

Austin starred as a wide receiver at Oak Ridge High School and garnered many awards. He was a PrepStar and SuperPrep All-American as well as being voted Northern California’s Most Valuable Player. During his senior season, he recorded 60 receptions for a total of 978 yards and 18 touchdowns. In 2004, Collie became an Eagle Scout. Collie’s hometown newspaper, The Sacramento Bee, named him Sacramento Area’s Player of the Decade (2000–2009).

Austin retired from football in 2016 after a series of devestating concussions and head injuries. He has since become an advocate for traumatic brain injury and has worked extensively with victims of head trauma. He is currently an Account Executive at Jolt Advantage Group, where he leads a business development team in the placement if Robotic Process Automation services applying his lessons learned from playing alongside NLF legends Peyton Manning and Tom Brady to the corporate sector.

—

Professional athletes grab our attention because of their physical ability. It’s usually an impressive physical ability that most of us even in our glory days could not even come close to on their worst days. What we often look past is the mental aspect of the professional athlete, the unwillingness to compromise a high standard when that standard is reached consistently and then the movement of that standard to a higher level when it’s achieved. It’s an endless need to become better tomorrow than they are now. These are stories of personal and professional growth. The physical ability is there but how they approach the mental aspect is something that has intrigued me more and more as I’ve learned more about professional athletes. Life is full of tough decisions for professional athletes, there’s extreme success and devastating setbacks.

In this episode, we have Austin Collie. He set and continues to hold records in the NCAA and at BYU even becoming a member of the BYU Hall of Fame. He’s personally evolved as a man, husband and father through his mission, his dedication to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. He’s played alongside Peyton Manning, Tom Brady, Reggie Wayne and under Bill Belichick. He’s played in the Super Bowl. Yet he’s also suffered injuries and concussions that ended his career. Unexpectedly, he’s forced to transition to a different career, in a new field, something other than the pursuit of his dream to play in the NFL. Yet through this journey, he’s exhibited the nine characteristics of elite performance as we have defined them in Special Operations, drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, effective intelligence, team ability, curiosity and emotional strength. In Special Operations, we say that special forces it’s a mindset but it’s a mindset to be a professional athlete.

—

Austin, welcome to the show.

I appreciate you having me. That was a great intro and honored to be included or at least following the same description as what the Special Ops had to fall under or had to carry.

There’s a lot of correlation and there are many places that we can start. Football has been a part of your life for a long time. Out of high school, you were a SuperPrep All-American. You were voted in Northern California as Most Valuable Player. In your senior season, you had 60 receptions for 978 yards and 18 touchdowns. I played center and defensive end when I was in high school. They threw the ball to me one time when they tried me out to be a tight end and I dropped it after it hit my hands and they said, “You’re going back to the line.”

You also graduated high school with a 4.0 GPA. You were recruited by Stanford, Arizona, Arizona State, Washington State, Oregon State, Colorado, Utah, UNLD and you chose BYU. Your father went there and your brothers played there. You’re a BYU legacy family and you go and you had instant success as a freshman. You won the Mountain West Conference Freshman of the Year. I start here at the beginning because your early life is where it was ingrained into you that success is earned and perfection is required to operate at an elite level. You credit your parents and they said that once you start something, you’re not quitting no matter how miserable you were.

Your father, Scott, talks about competition as a driver of your perfectionist mindset and he said, “I believe that people are afraid to be put in a position to reach down and pull the best out of themselves. Competition does that. You’ve got to learn how to lose properly and improve things that put you in a position to lose.” To do this, in my mind, requires an incredible amount of integrity and humility. I wonder what it is about these values, these things that your parents taught you about the competitive spirit in your early childhood that shaped your mindset and the diligence and how you approach a challenge.

My dad was dead on, the only way that you’re going to get better is if you put yourself in an uncomfortable circumstance. If you put yourself out there and make yourself vulnerable in finding out what your weaknesses are because at those moments, that’s when you find out what those weaknesses are. It’s through losses, trials and competition. When I was little, every single day, me and my brothers would go out front and compete. You quickly find out what you were good at, what you weren’t good at and what you needed to work on. That was with life in general. I wasn’t ever afraid to lose because I knew, at the end of the day, I was going to find out what my weaknesses were. I would eventually take those weaknesses and make them into strengths.

That’s an interesting point about transitioning the weaknesses in the strength. That’s something that’s permeated through your entire career. You talked about it in college, at the NFL level and it even came up after you when you worked with folks who are suffering from traumatic brain injuries and concussions. Taking those weaknesses and transitioning them into strengths. When I think about that quote from your father, “Lose properly and improve things that put you in a position to lose,” that’s where it’s quantified.

You quickly learn what you’re all about and what those weaknesses are during those losses. Only through that level of competition will you find out what those are. That wasn’t only in my childhood but that was every single day. Playing in the NFL, you’re constantly put in situations where it’s 100% competitive and there’s a winner and there’s a loser. I used to tell people all the time that the games are the easy part. Practices were the tough part. Practice is where you found the most competition where your job was on the line.

You look over during practice at the other field and the GM would be working on a new wide receiver. That new wide receiver could potentially fill your role if you don’t perform to that ability or you garner too many losses in those events of the competition. Competition is what catapults you into becoming who you are. You find out quickly in those instances who you are and what you need to work on to become better.

There’s nothing better as motivation than when you look over and somebody there is about to take your job. My high school coach did that to me once. I had a bad game and I was not playing well in practice and he’s like, “Come over here for a second.” They put another guy into my position and he’s like, “We’re going to try him for a little bit.” It’s like, “This is never going to happen again.” You take that motivation and you are about to go and rip somebody’s head off after that.

You played the position of wide receiver, one of the most difficult positions in professional sports. You have to be fast in a straight line but you have to be quick and nimble. You’ve got to stop and turn on an instant but you also have to be strong. You’ve got to fight for catches against a larger defenseman, linebackers, larger defensive backs. You also withstand some of the most vicious hits from people who are 50 or 75 pounds bigger running at you at full speed with the sole intent to knock you down and take the ball away from you. You also have to be incredibly smart and intellectual to understand the game. You have to be able to put yourself in the best positions to get open and catch the passes. You have to know the offense and you have to equally understand what the defense is going to do, number one, proactively against you but then also reactively depending on what you in the offense does.

You’ve been asked previously, what made you so hard to defend as a past catcher? What made you good? You said, “I knew that I wasn’t going to be the fastest. I wasn’t going to be the quickest or maybe the most athletic. I recognized early on that what I could do well was catch the ball and work on the fundamentals of route running. I knew the better I could run a route, the more I understood leverage and separation, the better off I was going to be. I tried to recognize that early on and work on my craft day in and day out.”

You’ve also been highlighted as an example for other players and the diligence that you put in studying in Gainesville, learning the playbook and perfecting your knowledge of the other players. Our default position as a type-A personality is that we can be the best at anything we do, “It doesn’t matter. Put it in front of me and I’m going to figure it out.” When did you realize that there were others who are going to be bigger, faster and stronger and that you would have to do something else to gain an edge over physical ability?

I’d say from the moment I touched the ball. Growing up in California, there’s competition and there are guys who are better than you everywhere. In a position that is primarily featured through speed, quickness and God-given athletic ability, you come to find out pretty quickly that you may be a guy in the middle of the pack. I had to quickly take a look at what my strengths were, find out what those strengths were and leverage those strengths as much as I could to help get me at the top of the pack and offset those things that maybe I didn’t have. I wasn’t slow. Going into my freshman year, I would say that as I was pretty fast. I was a 4-4 guy.

I went on my mission. Once I came back from my church mission, I had a bad high ankle sprain that I never let heal because I demanded that I played every game and didn’t listen to the advice of some of the medical professionals. That affected my speed overall. I wasn’t extremely slow but I wasn’t that 4-4 kid in my freshman year. I wasn’t like the guys that were running around me nor was quick. I was of average height and average size. The one thing I knew I was good at was running routes and catching the football. With my understanding of leverage, angles and spatial awareness, I knew I was above average at that. I made sure to sharpen those tools that I had.

We’ve spoken with a few folks who have talked about daily preparation, their daily routine and their daily ability to put their nose down and start grinding it out. We spoke with Lisa Jaster. Lisa was in the first class that was integrated to bring women into Ranger School. She was the third female graduate of Ranger School. We also spoke with Selena Coppock who’s a comedian in New York City but she had a great quote where she says that comedy becomes successful and you become successful as a comedian ten minutes at a time over decades. I think about what you’re talking about here. Every day you had to go out there and start to become a little bit better at route running and pass-catching. What were some of the things that you thought about to say, “I’m not going to go in early now. I’m going to take the extra reps. I’m going to put in the extra time.”

[bctt tweet=”Take your weaknesses and turn them into strengths.” via=”no”]

I see it as a mentality. You have a goal. You have this long-term vision of where you want to be and that certain things need to happen for you to get there. One of those things is being better than the competition. With that in mind, you know that someone else is out there working at that moment in time. As cliché as it is, having that mindset does truly help. At least that’s what helped me and continued to push me. If there was somebody that was going to get better right then and there, it was going to be me. I wasn’t going to let somebody, wherever they were in the world, outwork me.

Thankfully, from the teachings of my parents, the players that I played with in the past and my siblings, the work ethic that they’ve all exemplified and had only helped me in that quest of having that mindset that there might be people who are stronger, faster, quicker and more talented. There’s one thing that I could control and that was how hard I worked. I was going to make sure that no one was going to outwork me.

You go to BYU and you have a wildly successful freshman year. You stepped away from football for a time after that and you conducted a mission under the church. You stated, “The mission is the hardest thing I’ve ever done. It may not be so hard for others but for me It was.” Can you talk about that mission and what is it? Why did you choose to step away from football and risk coming back to an inferior physical state to conduct that mission? Also, what was hard? How were you changed?

In our church, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, we’re often referred to as Mormons. You have an option when you turn nineteen but now it’s changed to eighteen years old. When I chose to go on a mission, it was nineteen, you have an option to go and serve two years in a country or a place that’s not of your choosing. It’s picked for you. I was blessed with the opportunity to go to Argentina in Buenos Aires. You go from 19 to 21 and teach about Christ, His gospel, His teachings that are found in the Bible and a book we believe to be the truth as well as, which is the Book of Mormon and performing service for the people of Argentina or the people of whatever mission you were called to.

You did that for two years. You only get to talk to your parents two times a year, once on Mother’s Day and once on Christmas for about an hour. The other type of communication you’d be able to have would be email or writing letters, which you got to do one day a week. As a nineteen-year-old kid and have never been to a different country, having to learn Spanish and to be able to communicate those things, we were knocking doors, going from appointment to appointment, building houses from 9:00 AM until 9:00 PM and getting up at 6:00 or 6:30 to do Bible study, that was every single day for two years. When you’re a nineteen-year-old kid who had some successes freshman year at BYU and football at the time was your main priority, there was some pain getting used to that regimen, getting used to that schedule and getting out of that mindset of football being a priority.

Thankfully, I had a great mother, father and an older brother that kicked me in the butt when I had the thought of not going on a mission and said, “You need to go on one.” My older brother served as well in Brazil. He had gotten home off his right before I was about to go on mine. I honestly had thoughts of not going. It was something that was a priority to me at the time. Thankfully, my brother said, “This is something that’ll change your life forever. Life is not only about being a football player but it’s also about being a husband and being a father. There wasn’t anything that could prepare you more than what a mission could.” He was 100% right. It changed my life forever. It was the hardest thing I ever did having to put football to the side for two years and think about others and Christ rather than myself but I’m glad I did. I wouldn’t be the man now without it and without having gone through that experience.

You reference a lot as being one of the takeaways is the concept of selfishness versus selflessness. You quantified it there a little bit when you said that you were maybe a bit selfish prior to that and that experience on the mission taught you about this concept of selflessness. That then carried through in your ability to forge a better team and be on a team to build something whose component parts are greater than the individual. Can you talk a little bit about what you took away from that in terms of the selflessness aspect and how you apply that in the next stages of your life coming back playing at BYU going to the NFL?

It’s human nature to think about number one, to think about yourself and how things are going to affect you. When you spend two years being forced to think about everybody but yourself, you understand and start to appreciate the happiness that brings and also the appreciation or understanding of the fact that there’s a bigger purpose or a bigger plan than what you had thought. It doesn’t just involve you, it involves others. It’s no different within a team environment. You’ve got players who think about number one all the time. They think about how things are going to affect them and usually on that team, that can be cancerous especially if you get all 53 players thinking that way. I’ve been on a team that’s taught that way and it was not good. It was only for a short bit but when I was on that team, it wasn’t fun to be around.

Thankfully, being on the Patriots and being on the Colts, I can’t talk enough about the selflessness that went on within the Colts. You got that team type of mentality. Everybody forgot about themselves and put more priority on what the bigger plan was and what their part was going to be in that plan for the betterment of the team. If you want to have a successful career, the question needs to be, “How can I help the team? How can I make the team better?” Not, “How’s the team going to make me better? What’s in it for me?” Those are truly the things that separate great teams from okay teams especially in the NFL. The Patriots too are no different.

You come back from the mission, you have two more years at BYU and wildly successful set records in 2008 across not only BYU records but also NCAA records for all of college football. I was thinking about how I was going to quantify this portion of the conversation and I had initially written down, “I will ask him how did he do when he came back from the mission physically.” I’m like,

“Obviously pretty well considering he set all these records and went to the NFL.”

On January 9, 2009, you announced you’re leaving BYU a year early to go to the NFL Draft. The decision for a senior to forego their senior year creates polarizing conversations at times for talented collegiate athletes. Some believe that it’s in the best interest of the student-athlete to stay and finish school if you think about long-term after football careers. Others see the senior year as an opportunity to get hurt and ruin chances of going into a professional career. The risk versus the reward of staying and maybe coming up 1, 2 or a couple of positions in the draft or even getting hurt isn’t worth it so you got to go and forgo the senior year.

As leaders, we have to make decisions based on what we know at the time with an understanding also of what we don’t know. The best leaders know that they can’t keep the status quo if there’s an opportunity to do better. I think about this decision-making in that concept. This is one of those decision points. For you, why did you leave college a year early and enter the draft because this was rare for a BYU athlete especially for a BYU wide receiver?

It would have been easy for me to stay. To provide a little bit more context to the situation, all my good buddies were staying for another year. My quarterback and a lot of the offensive weapons who are good buddies of mine were staying for another year so I had every excuse to stay but I got to the point where I asked myself, “What else do you have to prove?” At that point, statistically, I couldn’t have done any better the following year and knowing that the only thing I could do is match what I did in my junior year or do worse. Unfortunately, if you do worse, you’re not going to get nearly the amount of clout that you had and the momentum of things going into it.

I’m not going to lie, part of it had to do with the fate that I had and getting an answer from God and my wife and me praying about it. When I get an answer, I don’t doubt it. It was one of those things that felt right and my wife felt right about it at the time. In hindsight, looking back on things, it was probably the best decision we made because I was able to play on a phenomenal team. Had I waited for a year, I don’t know if I would go to the Colts. Honestly, I couldn’t have had a better experience had I played on any other team at that time. Going to the Super Bowl, getting the opportunity to start in the slot and getting to play with the guys I played with. Those guys taught me a lot not only about football but about life and about being a dad and a father. It was a phenomenal locker room. There were a lot of great leaders in that locker room. It made me feel at home.

That was 2009 when you were drafted in the April draft of the NFL fourth round, 127th overall. It’s interesting, in the 3rd, 4th and 5th rounds, a lot of people say, “If they don’t go in the first couple of rounds.” The core of the team is built in those rounds. I truly do believe that. You go in the fourth round. This is Peyton Manning’s team at its peak. Your other players at your position are Reggie Wayne, Pierre Garcon and Dallas Clark at tight end and you impressed Coach Jim Caldwell. You were third on the depth chart in 2009 as a rookie.

That team went 14 and 2, went to the Super Bowl, lost to the Saints, unfortunately but that team was also 14 and 0 and somehow lost two games at the end to the Bills and the Jets, which we could talk about it offline. As a Patriots fan, I can’t understand how you would allow that to happen. I do know that there’s something against the Jets that was over 100 yards for you. You had a good game against the Jets. There are a lot of guys who play college football and a lot fewer who play in the NFL but it truly is the best of the best.

[bctt tweet=”Competition is what catapults you into becoming who you are.” via=”no”]

We’ve spoken before with Olympic gold medalist Laura Wilkinson who won Olympic gold on a broken foot in 2000 in a ten-meter platform diving. When we talked with her about the mindset, the fact that once you reach a certain level whether it’s the Olympics or the NFL, physically, there’s not a tremendous amount of difference between all of the athletes. In football, certainly, positions play a big factor in that. The big difference is the final 1% in the mentality, the way that you consistently approach the mental, emotional and personal preparation to prepare for the competition at that level.

Can you talk about the difference between college football in the NFL, that level of competition, the skill, the preparation from the mental and emotional standpoint? We’ve seen great college football players go to the NFL and not make it. JaMarcus Russell and Ryan Leaf come to mind as two of the big ones. How do you make that adjustment and continue to perform and get better when everything has been raised?

I remember going into my first practice with the Colts. As an outsider watching over the years and things that you hear, you would assume that the best players took a casual attitude towards practice. Maybe not practicing every single day and taking some time off to make sure that their bodies are right. I was throttled when I found out from the get-go, from the first day, the guys who were the stars of the team, the Reggie Waynes, Dallas Clarks, Jeff Saturdays, the Paytons, Gary Bracketts, Dwight Freeneys and Rob Mathis are often the ones who worked the hardest during practice. Those were the guys that never missed the practice if they could help it.

That made sense to me. You put in the work, you become the best. That makes sense to everybody but typically you may hear different things. Having not been a part of the team or not been on that level, there might be some players who were given every athletic talent and capability and get away with maybe not practicing 1 to 2 days. Sure enough, on day one, those are the hardest working guys. Those are the guys who put in the most time. Their level and attention to detail especially with Peyton and the way that he prepared for each and every single game is nothing I had ever seen. I thought I worked hard in college until I got there and I realized that I need to up my game.

These guys understood that talent wasn’t given and that it was earned. Wins weren’t given, they were earned. They’ve been around the league long enough to understand that and to see it. This was the most winningest organization from 2000 to 2010 and it wasn’t by coincidence. These were hard-working guys. They had all the talent in the world. I’m sure they could have gotten away with not practicing 1 to 2 days a week but they refused to do it because they all had that mentality that they wanted to be the best and that they wanted to win every single game that they played in so they prepared like it. That was an eye-opening experience for me. I pride myself on being the one that worked the hardest but once I got there, I was just another guy. I knew I had to up my game and match that level of intensity and preparation. To be honest with you, I hit a level that I never even knew I had because of it. That’s why I’m forever grateful to those guys for the example that they have set for me.

You said of Peyton Manning, “He demands perfection,” and then you said about yourself, “Drive is something you’re born with. There are many people who are more athletic and have more God-given abilities than I have but the one thing that separates me is the mental aspect. Everything has to be perfect. I can’t just walk away from the practice after feeling sloppy or running the wrong route. It has to be corrected.” I like the last part of that phrase, “It has to be corrected.” That’s something we don’t think about in elite performance. We say, “We get better next time.” It’s the fact that you quantify it in, “It has to be corrected now. It has to be fixed. It cannot go on any longer because if we don’t fix it now then we have to start tomorrow trying to fix it.”

That’s a waste of a day. You want to make sure that whatever corrections need to be made are made the same day that the mistakes are realized. That was a big thing for me. I don’t think I can leave the field knowing that something was off or something wasn’t right.

I want to discuss team ability. I want to talk about the idea that the team is more important than the individual that some of the parts are greater than the whole. Everyone is working towards the same goal. I was having a conversation with the head coach of the Boston University men’s rowing team. In college, I was on the rowing team at BU and I support the team now as much as I can. We were discussing the concepts of accountability versus responsibility. That responsibility is the sense that we have roles to fill with specific jobs to do but accountability is that we have a duty to fill those roles and to do those jobs at a certain level of proficiency. We have that accountability to do those jobs without compromising and without excuse. There’s an expectation of performance by our teammates and our leaders that we must uphold and be accountable for.

This concept of responsibility versus accountability is what I believe creates long-lasting and resilient organizations that stand not only the test of time but also the shocks to the systems like personnel changes, wins, losses, all the things that can derail a strong organization. There’s also a concept with accountability and responsibility that once we meet expectations, we have to reset the bar, we have to raise it and then we have to strive for that the next time. You played for Bill Belichick, Peyton Manning and Tom Brady but specific to the Patriots, they have this do your job concept.

In the Special Operations, they are the best teams and the best teammates won’t even let others come in and critique them because by the time they get in a room where someone is about to tell them they did something wrong, the best operators will stand up and say, “I did this wrong. You can’t tell me I did it wrong because I beat you to it to accept responsibility and accountability that I let the team down.” You played for two of the greatest organizations at professional sports at the height of their dominance. Can you talk a bit more about this concept of, do your job accountability and responsibility? How does it build, unify an organization and create that team that doesn’t let anybody off the hook?

It goes back to understanding that there’s a bigger plan in place or there’s something bigger than you. If you’re able to capture that in the hearts of all the players, that’s something that is extremely unique. The Colts and the Patriots had it during their time of dominance. You talk about somebody standing up in a room, accepting accountability prior to anybody coming forth or coming to them with it and having that ability to accept that responsibility and to be accountable for their actions. Everybody on our team especially the Colts, you didn’t have to tell them. When we went back and watch film, it was something to just check out the list because, at that point in time, everybody at practice knew exactly what they had done wrong in that practice. As a matter of fact, they’ve probably already gone in and watched the film on their own prior to the film session to see what they did wrong.

You only get that when you get players looking outside of themselves and constantly wanting to get better for the entire purpose of the team, be a part or be a piece of the puzzle. Capturing that idea that, “I’m a piece of the puzzle in this grant in the grand scheme of things here and if I do not meet that accountability, if I do not fulfill that responsibility, I will throw the puzzle all out of whack.” That’s a hard thing to do especially with professional athletes because they do have this tendency to think about, “I’m the only piece of the puzzle. Whatever affects me is the only thing that I care about.” Getting a team of 53 professional athletes to think along those same lines and saying, “Here’s my responsibility and I’m going to hold myself accountable to it for the betterment of the team, for the bigger picture, for the long-term goal of the team.” That’s a unique thing to do if you’re a coach. Bill Belichick and Coach Caldwell did it.

A sign of that would be any pregame pep talk. There really was no pregame pep talk especially with Coach Caldwell. It was just, “You guys know what you got to do. Let’s go do it.” That’s all that needed to be said prior to a game. I’ve been on teams where there was a lot of hoot and holler and commotion trying to get guys fired up trying to reinforce what that responsibility is and the accountability that they would have to have on the football field. Typically, those are the teams that don’t have it. The teams that do, nothing needs to be said. Everybody knows exactly what needs to be done that day you hit the field.

Let’s take it a step deeper to the player or the teammate level chemistry as it’s called in a lot of organizations between those within an organization that a certain level of trust must be built. Chemistry isn’t just built on the football field, it’s built off the field. Hanging out, knowing each other and developing what you called the sixth sense. We’re in a world that sits at the back end of COVID where the leaders of organizations are trying to decide, “Do we bring our teams back in? Do we bring everyone together because of the importance of personal interaction or do we keep them separate because remote work has proved to be somewhat effective?” We’re still probably trying to put a number on what percentage of effective we’ve been. Maybe some organizations have become more effective in their business models.

Much happens when you sit in a room with someone day in and day out. Relationships can only go so far when you’re on a computer screen and you have scheduled time blocks to communicate with each other. Outside of those time blocks, it becomes almost an inconvenience. There’s no greater need for chemistry and the bonds in which you instinctively know what your team is going to do in certain situations as the quarterback-receiver relationship. You have to be in lockstep. There has to be total trust. That was something that we, in Special Forces and on Special Operations teams, develop after years of training and conducting operations and deployments together where we begin to know each other better than we know our own families. What is it that is important about the chemistry between teammates in an organization? How do you build it, not only in athletics here in the military but also in the private industry as you sit in your role now? How does chemistry help to build the entire organization stronger?

In nowaday’s situation, to be honest with you, I don’t think you get that at all. There’re ways that you can maybe catch a glimpse of it or you can orchestrate that team type of environment but there’s something to be said about being with somebody 8 hours or 9 hours a day, both in the office, out of the office or on and off the football field. The more you hang out with somebody and the more you see how they react in certain situations, you start to develop this sixth sense of how they’re going to react in certain situations. You get to know each other and you start to become this adhesive bond over time as a team. It was the same thing when I was on the mission when I had a companion. It was the same thing when I was a receiver with Peyton. Taking those opportunities to hang out together, watch film together and understand and get on the same wavelength as him.

[bctt tweet=”There’s one thing you can control and that’s how hard you work.” via=”no”]

Before COVID, I’m sure there’s a lot of business professionals that will tell you the same thing. There’s not getting that same level of camaraderie and that same adhesiveness that existed before. You may get some of it but not having that ability to pop your head in the office and say, “Can you help me with this?” “What are your thoughts on this?” Everything having to be scheduled in these time blocks tears it apart a little bit. It doesn’t become as sticky, you could say. This goes along with accountability.

When you get a team that understands what level of accountability they should have or what level of accountability is required, they all understand it and they all accept it. When you’re working together and you know what the long-term goal and the vision of the team is, that naturally starts to happen over time but it only happens when you’re together in person fighting the good fight or getting your hands dirty together. I venture to say you can say the same thing with Special Ops. That’s the whole reason why you probably knew each other better than the family did. That was because you guys went through things together that maybe you didn’t go to go through together with your family and those things could only happen when they’re being done in person whether it was on or off the battlefield. All those things matter.

The team room was a combination of a lot of different places. It was an office, a training facility, sometimes it ended up being a dojo where you guys were fighting it out. It was a therapist couch and a bar. It’s similar to a locker room. That was the place where it was the safe place. It was where everybody went in and it didn’t matter what was going on in that outside world. You could talk about work, relationships, family and you could throw each other around and just get some aggression out.

Peyton understood that better than anyone which is why during the offseason, we’re always doing things together as an offense. Going golfing, throwing and dinners. He understood that. I’d like to say it was because he liked us but there was a higher purpose for him doing that. He understood that’s where teams are made. Not only in the film room and on the field but after hours.

He liked it but he also liked winning. No success story comes without adversity. November 7th, 2010 game against the Eagles, you’re hit on both sides of the head by two defensive backs, knocked unconscious and taken off the field on a stretcher. I watched the video about six times. December 19th, 2010, you got hit in the head by Jaguars’ linebacker and knocked out again. It’s the second concussion-related injury that year and ended your 2010 season.

In the 2012 preseason game against Pittsburgh Steelers, third concussion in the career and then later on in the 2012 season. Again against the Jaguars, you suffered a ruptured patellar tendon in your right knee and you miss the rest of the 2012 season and then released by the Colts later on at the end of 2012. In 2013 briefly with the 49ers and then go on remainder of the season with the Patriots. Concussions and head injury protocol have come front and center in the NFL over the years. When you suffered these injuries, that was probably more at the beginning of the concussion and head injury awareness drive that they’ve been on. There was a lot less scrutiny on those plays and events that lead up to those plays and what’s allowed but then also how they treated them, the mitigation factors and how quickly they allow players to go back out onto the field.

Referencing the head injuries, you stated, “My concussions were visually devastating. They didn’t look good. Combine that with the public’s perception of concussions, it was no surprise that no matter where I went after that stretch, I was constantly being reminded of my head injuries whether it was people asking me how my head was or asking me what I do about it. I had people texting me, tweeting me, emailing me about my head. All I ever heard from the public in the media was, ‘Collie will have dementia by the time he’s 40 and he should be taking his family into mind.’”

How did these head injuries affect you? How did it affect your play? You also approached treatment in a very open and positive mindset. You had a different perspective than the media and the public did on this stuff, which I found was interesting. You referenced real hard medical data. I’m hoping you might be able to talk about that, how it affected you and then how you approached having to come back from that and combating that fear to get back out on the field.

At that point in time, when I said those things, I was a young kid who was just looking to get back on the football field. I couldn’t have the scrutiny against concussions affect that. Looking back on it, if you were to ask me now how I felt about the concussions, it is a real thing. The effects that I’ve had from it I would hope are chalked up to old age and being a father of four but there are days where there’s a maze. Especially transitioning out of football, a lot of guys that have had previous head injuries have a hard time with that. Struggling with that identity as a football player and having to redefine themselves combined with a level of brain dysfunction that they wouldn’t get had they not taken a few shots to the head.

For me, it’s a hard topic because there are so many things coming out. There’s little research that that was being done when I was taking it but now that more research comes out, the more it has been a little bit of an eye-opening experience. Now that I’ve stepped away from football and haven’t had that temptation to get back onto the field and have seen things in a bigger picture, you can’t help but respect that. I’d like to think that maybe I go back in that moment and take a better look at what my situation was and maybe said some things a little bit different than what I said back then and given the events a little bit more respect than what I did back then.

I’ll tell you that the perspective that you took back then is no different than every Special Operator has when they’re sitting there and they have a face injury over the course of their career. I suffered a stroke in my right eye while I was deployed to Iraq. They medivac me to Germany but it took two weeks for me to be medivac because I kept telling them that I would go “onto the airplane” and I never showed up to the airplane until my battalion commander called me one day and said, “You have no choice but to get on that airplane.” Even then I thought, “What if I just don’t get on the airplane?” I had multiple back injuries. It’s the same thing. I’m in the field hospital getting injections into my spine and going out on an operation the next night after steroid injections. I look at something that we have termed operator syndrome

In another episode, we had Dr. Chris Frueh who works very closely with Special Operations military veterans and elite performers in a lot of different industries but he talks about an operator syndrome. That’s what he calls the effect of a high performer when they’ve pushed for too far for too long and their physical, emotional and mental stability begins to erode due to decades of overuse in high-intensity activity or what they call allostatic load on all of your systems. The average special operator, before the received treatment for systemic issues physically was thirteen years. They wait thirteen years before they go and say, “I have a physical problem that I need to address,” which over the course of a Special Operations career if you’re in something like Ranger Battalion, that could be twenty deployments. Deep at that point before you accept that you have a problem.

I bring this up because in the best cases, people seek therapy and a vacation. In the worse spots, they become destructive to themselves, their families and their organizations. In football, I think about someone like Junior Seau, a legendary Hall of Fame linebacker. The belief is he suffered from CTE and committed suicide. Since 9/11, 7,000 service members have been killed in combat or training but 120,000 have committed suicide in that same timeframe.

I appreciate you being open and candid in this conversation about this difficult topic because it is difficult to discuss when you think about all the people who are affected by these things whether they’re athletes or they’re veterans. I’m wondering if you could maybe comment on having operated at an elite level for so long, had much success and now, as you’re able to take a step back and look at it, what’s the advice to those who are in those positions now where maybe there’s a sense of balance that can be learned from the perspective that you now have?

You’d hate to say that there is a balance. I don’t think you can go into those types of situations functioning at a high level. What makes elite athletes elite is they have one mind track. There’s one central focus and that is becoming the best, being out on the field and constantly getting better at the game. If you take any of that away, I do think you miss out on the opportunity on maximizing your full potential at whatever it is that you’re looking to do.

Everybody I played with that’s been great and they got blinders on. It is like, “I want to get better. I want to be the best,” and it’s consuming but there is no happy medium. I don’t think they get to where they’re at with the happy medium. I would say the same thing about Special Forces. I can imagine if they’re going in, they’re going with two feet, they’re putting those blinders on as well on how they could become the best of themselves, the best soldier and continuing to improve. That is the one track that continues to play over and over again in their mind.

[bctt tweet=”You put in the work, you become the best.” via=”no”]

I do think it is essential that you don’t identify as only that. One of the things that have helped me is I’m a husband and I’m a father. Those things hold a massive part in my life. That has given me my identity as I transitioned out of football where I don’t think a lot of guys do that. You can be focused entirely on getting better, on becoming the best but at the same time, not identify just with that one thing and not tie who you are into that one avenue. The guys that struggle in the NFL have done that. It’s a whole combination of things but it doesn’t help that all they’ve been known and all they’ve known themselves as is a football player and that’s it.

Any transition is so difficult. In 2016, you announced that you’re retiring from professional football. You achieved your dream of playing in the NFL but now what? I remember the day I left the Army. It was the hardest and the scariest day of my life. Everyone I knew, everything I was good at, everything that I understood in my career and I sacrificed everything for that career and that life was now in the rearview mirror of the gate at Fort Carson, Colorado. I remember looking through the windshield going, “I have no idea what’s ahead of me.”

Football is a business. It’s a $16 billion business in 2019. The numbers of projection for 2021 is going to be $16.5 billion. We did an episode with former Top Model Emily Sandburg Gold where she talked about when she was modeling in her young career, she always kept in the back of her mind that she had a short shelf life. Eventually, someone younger, more trendy would come around and it would displace her. In Emily’s case, it ended up being Gisele. Football is similar. As long as you can produce on the field, you have support. Once you can’t, it’s not personal. It’s a business. We saw this even with Peyton Manning. After all the years he put in the Colts and eventually the business says, “You got to move on.” It’s happened to many greats since.

You talked about the transition and you said, “I don’t think a day will go by that I won’t wish I’m playing football. It’s the game I grew up playing and I’m always going to want to be out there competing. I realized at a young age that I was good at this game and I enjoyed improving. Part of the fun was challenging myself in order to see how good I could get and I’m going to miss that part of it. I’ll miss game days. I’ll miss preparing for game days and I’ll miss the feeling that you get the night before a game. Those butterflies are hard to replicate in everyday life. Other than starting a family and serving my church mission, nothing has been more gratifying and rewarding than my four-year member of the Colts. It was the time of my life and everything I pictured as a little kid.” Did you think about life after football when you were playing? What would that bring and how did you accept that transition? How did you take a step back, reset, refocus and say, “I’ve learned all these things about drive, perseverance, resiliency and grinding, that got me to where I am as a professional athlete, now I have to apply them to the next chapter of my life?”

Thankfully, the end came over time. It wasn’t just this abrupt like, “You’re done.” It started to trickle down or erode as injuries came into play, concussions and other concussions then my knee and ultimately, going up to the CFL and finally getting closure on the game. I did have some time to think about it. I don’t think you can ever comprehend the end until the end has come. Until that moment, you’re driving in the car and you look back in the rearview mirror you’re like, “It’s done.” Seven years later, I’m still comprehending that it’s done. I’ll go out and watch my boys play. They’re at a BYU football camp and it’s in the BYU football stadium. I do have those moments where I look around and I say, “I’ll never get to play this game again, ever.”

It feels like yesterday that you were you’re catching passes and scoring a touchdown. “I could go on and do it now.”

You think you could. I feel like I was eighteen yesterday. Those times are tough. When you think back, you just had that moment of realization again, “This isn’t happening again.” To say that it’s easy, it’s not easy even seven years after I’ve ended. Until the day I die, I don’t think there’ll be a day where I don’t miss playing ball. Every single player can tell you that exact same thing. If they tell you any different, they’re lying.

You can’t play something since you’ve been eight years old and be the one thing that motivates you, pushes you and drives you and then that comes to an end when you’re 30, 25 or whatever years old and say, “I don’t miss it.” That’s them trying to tell themselves that to get over it. That’s what I think because I’ll be straight up with you. There won’t be a day where I don’t miss it and a day I don’t want to be back on out on that field, injuries and all. It’s what I’ve known for twenty-plus years and I love the game.

Fortunately, I have boys now that I get to watch and get a little bit of that, a little bit of those nerves before game day, the night before game day or the night before the competition. It brings a bit of that back but I won’t get that again. It’s extremely tough but thankfully, what you are forced to do is find the next thing that you want to become great and see how far you can get in that. See where your potential is in that and how you can elevate the ceiling in whatever venture that is. Now, I’ve gotten that opportunity so we’ll try and make the most of it but I’m real with myself in thinking that it’s probably not going to be like football. I don’t love it as much as football, that’s for sure.

There’s an impact piece to it. I certainly suffered that when I got out and started working in the corporate sector. You’ll think, “I was in the basement of the Pentagon,” in the rooms that you think are only in the movies and then you’re out and you’re doing something different. For you, you’re on the field with Tom Brady, Peyton Manning and all these greats and you’re in the Super Bowl and then you’re watching on the couch going, “I used to be there.”

Football Sunday is not a fun day in our house.

I could imagine. It’s not a fun day in a lot of people’s houses unless you’re in the Brady household. As long as you’re in that household then it’s the best day. Now, you’re at JOLT Advantage Group, a Robotic Process Automation service provider. You’re going to have to define that for me. I had to look that one up. The idea here is that there’s an ability to automate so much of what’s done on a software side of things, the mundane, repetitive tasks to bots and robotic software. Research out of LinkedIn shows that robotic automation is the second-fastest-growing emerging job market. Second only to AI and there’s a theory that you can free up human capital by giving many of these tasks away to this level of automation.

You’ve been the first to admit that you had no sales or tech experience prior to this role. I liked that acceptance in the fact that you have been open and honest about that. That’s one of the first things you talk about because it’s a core tenant of the Talent War Group. It’s something we talk a lot about here on the show. You hire for character, you train for skill. You don’t need a lot of industry experience to be successful in a role if you’ve demonstrated the characteristics that are required to succeed in that role.

You then can learn all the technical, hard skills because you innately have the soft skills that are going to be required for true long-lasting, sustainable success. You said, “People want to have a purpose in what they do. They want to make a change in people’s lives and they want to see results. I don’t think there are a lot of technologies that provide all three of those things but this definitely does.” First off, can you define Robotic Process Automation? How do you make the jump from professional sports over to the tech world and the front end of the VC startup world?

Robotic Processing Automation is basically emulating what humans do. All those mundane tasks, those drag and click swivel chair tasks that are performed every single day specifically in back-office use cases. Moving around data in Excel spreadsheets from one legacy system to another, that all can be automated seamlessly across any system or any enterprise solution which is pretty outstanding once you think about it. There’s no requirement for API connection or API calls. You can just take data from one place and move it to the other or perform a task across these different legacy systems or enterprise solution software.

It’s the second largest-growing industry behind AI but it has a bit of AI and machine learning tied into it. It is the next big wave, the next big thing especially in enterprise sales. The leader in the industry UiPath who we are a premier partner of will often say they imagine the day where everybody has their own robot assistant. From turning on your computer and logging into those systems that you use to perform the tasks, taking data from one place to another and performing it as exactly as you would.

These were the that got me excited. Before this, I was in an AI machine learning company. I was at a speech and language company called Canary Speech. What we did was build algorithms to assess and diagnose certain diseases based on biomarkers that we found in our voice. It’s an advanced level of AI and machine learning. It’s an advanced technology and truly novel technology. I still have a great relationship with the company and I’m still a small partner in the company.

I could not deny the potential that this RPA technology has and the part that it will play, not only in a single department but across an entire organization. That’s what’s unique about it. Everyone can benefit from this technology within an organization, company or corporation. The possibilities are endless for it. That’s what got me excited and made me make the jump to join JOLT Advantage Group. We talked about having a locker room type of mentality and this group is probably the closest thing I’ve come to that. We got a bunch of dogs in the company that is willing to pour everything that they got into making a sale and building up this company to be something bigger than us and I love it. I thrive in that type of environment and I love the people I’m working with.

As we close out, the Jedburghs had to do three things every day to win and be successful. They had three core fundamental foundational tasks. They had to be able to shoot, move and communicate. If they did these three things successfully every single day, it didn’t matter what challenges came their way, they would be able to focus on finding those solutions. What are the three things that you do every day to win and be successful?

I would say to communicate is one. That’s for sure. I have to communicate. If I need help with certain things, which I for sure do at this point in my career, I don’t hesitate to reach out. Stemming off of that, I’d say the second thing is to remain humble. As soon as I let my ego get in the way, that’s when I’m always taking a turn for the worst. Understanding and being okay with not knowing everything, not knowing what the right choices or what the next thing to do is, being humble enough to reach out to somebody and get that bit of information or get their advice.

Some of the best coaches and best players that I’ve ever worked with were always the most humble. Always looking for ways to get better and they weren’t afraid to admit that they weren’t the best and that they didn’t know it all. That’s extremely important. The third thing is don’t get outworked. Whatever you do, the only thing that I can’t control especially in this business is the amount of work I put into it. Making sure that I stay in that top tier of workers and always looking for ways to get better and move deals along. I’d say those are my three.

I love that especially the third, don’t get outworked. You’re right. The one thing that you can control is you and your attitude and what you do every day, nothing else. Other things can impact you but how hard you work every day is on you. First of all, congratulations on earning your MBA as well.

I have not yet. I was almost there and then we had our fourth child. I got my Master’s in being a father.

We talked about the nine characteristics of success and I always say that elite performers exhibit all nine at different points in their life. It doesn’t matter what they’re doing but they always will exhibit portions of the nine at certain points in time but in the totality of what they do, they have all nine. I say that and then I take one and I apply it to each one of my guests. For you, I think about the drive. The need for achievement, growth mindset, be better now than you were yesterday, continuous self-improvement, constant hunger to do more and take it to the next level.

You’re a perfectionist in everything that you do. You’ve displayed what we call the whole man concept that there’s a lot of different things that you’re able to do at a high level. You have a passion for anything that you get involved in and there’s a dedication to being the best. Otherwise, why would you do it? If you don’t approach it that way, is it worth your time? I truly appreciate that about you, your story and the success that you’ve had at every level of your career. The success that I know you’re going to have in this new role. When you take this attitude and this character and you apply it to this organization, it’s going to be something that the industry has never seen. I’m sure of that. You will advance that.

We talked about a time in 2013 when you traveled on a USO trip to Djibouti and I was there. I can’t give you the story now because I have to save it for hopefully one day when I have Peyton Manning on the show, I’ll talk about it. You were on that trip. I wish that I had also kidnapped you. We would have met then but I’m fortunate and thankful that we have since come together and our paths have crossed. We’ve got to know each other, had an amazing conversation and amazing story. I do wish you the best of luck. I thank you for being open, honest and providing some real true valuable lessons learned from a true champion.

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that. I’m honored to be on the show. I wish we could have met back then. Honestly, it was one of the best experiences I could have had at that point in time going out and seeing individuals such as yourself, being able to interact with them and see what a real challenge looks like not just on a football field. Respect to you and thank you for everything you’ve done for myself, my family and our country.

Thank you.