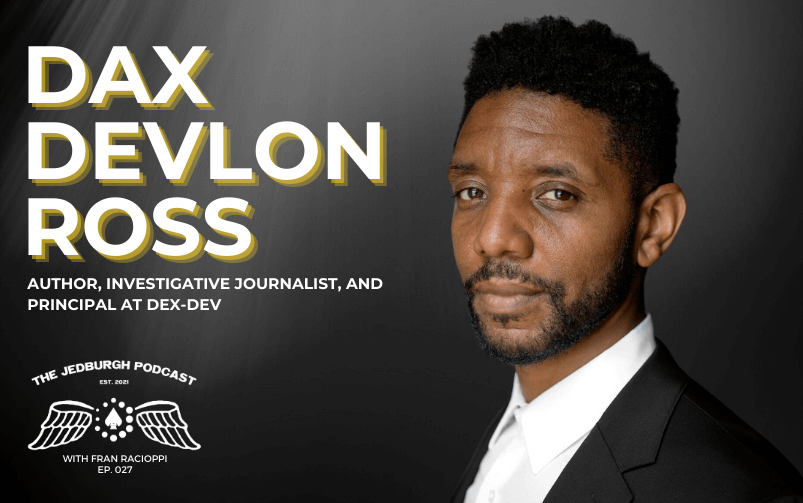

Race is an uncomfortable conversation. Recent events like the death of George Floyd and Breana Taylor sparked race conversations, racial tensions, movements like Black Lives Matter, and corporate action. These events have forced us to look inward and challenge our thoughts, perspectives, and views on race and the role race play in our conscious and unconscious bias. In this episode, host Fran Racioppi joined by investigative journalist, Dax Devlon-Ross to discuss his new book, Letters To My White Male Friends.

Dax and Fran break down the racial divide between black and white. They define and analyze present-day examples of systemic racism and why they exist. Dax shares his personal experiences of growing up in Washington, DC. We layout Dax’s LENS (Listen, Empathize, Notice, Speak) framework for how we move forward…together. And in a section called, Dax’s Decision-Points, he lays out his checklist for solving any complex issue.

—

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

Dax-Devlon Ross has led a career as an educator, non-profit executive, equity consultant, and journalist with a focus on social justice. After receiving his Juris Doctorate from George Washington University, he joined New York City Teaching Fellows where he taught in middle and high schools in Brooklyn and Manhattan. He later helped lead the national training and replication team at the Posse Foundation, one of the country’s foremost college access organizations. During his tenure at Bank Street College of Education, he managed the school’s partnership with the Corporation for National and Community Service. As the founding Executive Director of After-School All-Stars New York and New Jersey, Dax built, from scratch, a team of 60 full and part-time program, development, and operations staff serving more than 1,500 students across two states. Thereafter he served the organization as its inaugural northeast regional executive director, managing five-chapter executive directors while overseeing regional growth strategy, partnership development and management, donor stewardship, board governance, and chapter operations.

For over a decade, Dax’s social justice consulting practice has focused on developing disruptive strategies to generate equity in workplaces and education spaces alike. Dax’s clients have included: The Anti-Defamation League, The New World Foundation, The Posse Foundation, Fund II Foundation, Bard College, Kean University, and more.

Dax is the author of five books and his journalism has been featured in Time, The New York Times, The Virginia Quarterly Review, and other national publications. He was the winner of the National Association of Black Journalists’ Investigative Reporting Award for his coverage of jury exclusion in North Carolina courts. He is currently an investigative reporting fellow at Type Media Center, an alumnus of Coro Leadership New York, and a member of NationSwell Council.

Dax, welcome to the show.

Fran, thank you so much for having me. It’s a real honor to be here and to be part of this conversation with you.

I want to open this conversation with the caveat that this is a difficult and uncomfortable conversation. The topic of race, the social divide, the tension that lives between Black and White in our country, it’s as wide and as deep as it has ever been. Events like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor have ignited this discussion on race, diversity, equity, and inclusion that has led to everything from constructive conversations to corporate change to outright violence.

My passion, as you know, is telling the stories of those that drive change. This was a topic that I could not pass up. It’s a topic that I believe we had to tell here on the show. Change, as you have talked about in your book, is messy and not easy. The transformation of ourselves, our teams, our organizations is not always clean. Most often it’s ugly, personal, difficult, and hard. Too many people put it in the too-hard box and don’t talk about it. They don’t want to address it.

Real transformative leaders, agents of change, those who are dedicated to winning no matter the challenge, the stories we tell, are leaders who get in the weeds. They get their hands dirty. They lead from the front because you cannot lead from behind and through talking about it. You have to lead by doing. I boarded the plane. I came down here from New York City to Washington, DC because this was a conversation that I would only have with you in person.

To sit across from one of the leaders in the advancement of Social Justice and Civil Rights is truly an honor. You have termed your work discerning, deep, disruptive. Having read your book, Letters to My White Male Friends, I assure you that you have succeeded in becoming discerning, deep and disruptive. It is a pleasure to sit across from you. I see you as a like-minded partner. I’m excited to have this conversation about power over purpose, cover over comfort. Thank you for joining me.

I don’t know if I have had quite that introduction in a long time. For your readers, you did come down here to meet with me. Per book perhaps read but sight unseen. That means a lot. It’s a lot about your integrity, what you are up to, and how serious you are about the work that you are doing. Let’s get into it.

You wrote your book for me or people who, on the surface, look and may feel like me, White, male and educated. I grew up in a suburban town where we bust the Black students in from Metro Boston every morning. In the afternoon, we bust them home. Growing up, my Black friends are numbered, on one hand, 1 to 5. I can name them all.

You wrote in the book, “I write the letters herein to my White male friends because you are everyone’s target but no one’s focus. You and I both know that you hold immense power, wealth and status in our society. That power strikes fear and invoke intimidation. It instills a sense of incontestable authority and certainty. Consequently, no one ever speaks to you directly and challenges you to push beyond your comfort zones. In short, when it comes to conversations about race, White men are typically coddled and appeased.”

There’s no coddling and appeasement in this book, Dax. Often, there are a few if any punches held. It’s very direct. I appreciated that about this book. Why did you jump into this? Why are you looking at this problem and saying, “I had to be the one to take a stand to jump in and have this conversation?”

If you had asked me years ago, I had no real intention for this to be a conversation that I would be someone who’s in the center of or helping to drive in some way, shape or form. That’s the beauty of understanding when you are called in to do something versus forcing something on other people. I always tell the story days after George Floyd’s murder. I sat down to write a letter to my close friends without thinking of it as something other than a way to express some of what I was experiencing in hopes that they can begin to maybe approach these problems a little bit from a different perspective.

As I have said many times, I felt as though the care and concern that people were expressing was genuine and authentic but it wasn’t sitting, helping, and engaging with how my White friends are seeing and experiencing this separate and apart from me as a Black person. This isn’t just happening to me. This is happening to you, too. This is happening in your country as well. This is affecting your life in ways maybe that you aren’t consciously aware of but it is having an impact. Even if that impact is you feeling uncomfortable having a conversation about it, that’s an impact.

In many ways, that inspiration and motivation behind the book was a letter that then became a bellwether. Some people felt connected to it and felt they had been invited into a conversation at a time when they wouldn’t feel like there was much out there giving them an anchor in a way to push forward.

Lastly, for a long time, I didn’t fully appreciate the extent of my relationships across races and how different that was from some other people’s experiences. I grew up in a city in a time that, in DC, was very integrated into my environment. I looked at my soccer team pictures. We were probably 60/40, White and Black. Some students were biracial kids.

My authentic experience from the time I was a young person all the way to the point in my life in my 40s has always been weaving through, around and deeply intertwined with race. It’s very much an intimate relationship and friendship with White men, as well as my Black friends, my Latinx friends, my Asian friends. I don’t think that I ever considered that proximity and authentic relationship might have given me some credibility, and maybe even some language to drive a more intentional conversation at a point in time we needed to have one.

I want to ask about those early days because they are important. You admittedly came from a well-off family in DC. You went to one of the best schools in the country growing up. You went to a great college. You earned a Law degree. You said, “The White people that I knew lived in our neighborhood. I was not ducking bullets or dodging drug dealers. I never had to worry about food or where I would live. We took family vacations to Martha’s Vineyard in Jamaica.”

This background lit a fire in you. What you talked about bridging this gap and weaving through also made you more attune to systemic racism. I’m hoping what you might be able to do is define for me systemic racism but then also talk about how this upbringing shaped your views and made you more aware of it.

I resist the idea that I was well off. I embrace the idea that I was based on my father’s income, middle class. My father was a first-generation in his family to go to college and graduate from college. He was able to carve out a middle-class life for himself at a time in America where one could do so with even a modest income.

My mother was a stay-at-home mom for the first ten years of my life before she went back to work. I want to qualify that because that’s sometimes where people get tripped up around our conversations with race because we think it all comes down to your evidence of Black people doing fine. If other folks did what your dad did, then we wouldn’t have any of these problems without recognizing, in many ways, how he was an anomaly.

In many ways, even the people I grew up around were not anomalies because they were the ones in their families and communities who were able to get the education that created the conditions for them to be able to raise children in a middle-class environment. All of them, by large, was like my dad and my mom. My father and my mother grew up working-class in Richmond. Meaning, they had lived in homes but they didn’t have their own room. They weren’t planning to go to college. My parents had an eighth-grade education.

My generation took a huge leap. That was, in many ways, catapulted by policies and I write about those. Specifically, they were policies that we have aligned in our society like affirmative action or the Civil Rights Legislation in 1964. My father graduated from Howard two months before LBJ signed the Civil Rights Legislation into law, which then opened the door for my father as a young man in that generation of men and women to be able to access opportunities often in the Federal government.

That law, in particular, applied to Federal agencies and also to contractors, anyone contracting with the Federal government. Him, being in DC meant he was surrounded by an infrastructure that was systemically pivoting towards creating opportunity. Those are how a system can pivot to create opportunity or it can pivot to close off opportunity.

That opportunity can be closed off in such a way that it can manifest systemic racism whereas it’s not necessarily the case that you will read a piece of legislation or a policy that says, “Keep Black people out.” That’s not the way it’s going to read. What you will see is that there’s an impact that is being disproportionately felt by people who have a shared cultural or even socio-economic background such that it would be the case that it is a systemically racist policy. That’s what we would call systemically racist.

As one example that I use, Washington v Davis is a Supreme Court case back in 1976. It was set here in Washington, DC. It stemmed from two Black aspiring police officers here in Washington, DC. At that time, DC was already what was called a Chocolate City. It was a predominantly Black City. After what we called White Flight, that was precipitated as a result of the uprisings following Dr. King’s death in ’68. You saw a massive White Flight from Washington, DC Proper into the surrounding counties. By the mid- ‘70s, DC was considered a predominantly Black City.

In Washington v Davis, Washington was a guy who felt like, “I want to be a police officer in DC.” There was a test and it was called Test 22. This test asked a series of questions. You had to pass the test with a certain grade and score to qualify to become a police officer. What Washington arguing was that Black applicants for police officer positions in DC were disproportionately failing this test. The police department was like, “You all aren’t passing the test. That’s a failing on your part.”

Washington argues, “No. There are questions on this test that are only going to be known by people who will have certain sets of experiences.” He then takes this case all the way up to the Supreme Court. There’s one question about hunting licenses. Who’s disproportionately going to know and have access to a hunting license? What does that have to do with being a police officer in Washington, DC?

[bctt tweet=”People don’t have a deep engagement with how poverty even exists in our country in the first place and that it is, in many ways, structural.” username=””]

I don’t think there are a lot of hunting going on.

There are a variety of questions that have clear cultural implications. Meaning that if you grew up in a certain environment and are exposed to certain experiences, you will have a higher likelihood of knowing the answer to these questions and Washington was arguing this. The Supreme Court ultimately sides with the City of Washington, DC and saying that the test was not systematically biased. Even though a disproportionate number of African American people in an African American dominant city were not passing the test and therefore got a police department that did not reflect the city.

That particular decision goes on to have a huge impact on our legal system for the next 30, 40 years. It becomes the basis for how our criminal justice system can resist calls from advocates and activists around systemic bias. Inherent in it is by saying that a disproportionate impact or disparate impact on a certain community is not in and of itself enough to prove that a particular policy is racist. You need to show intent. We all know how hard it is to show intention. It’s very difficult. You need to find some documents that someone has signed or some statements they have made. It’s impossible.

What I argue is that systemically racist policies typically have an effect that is having a disparate impact on this particular group of people even though the writing and the letter of the policy might appear to be neutral because it’s applied. Different people from different backgrounds will experience it differently. That’s one way it can show up. It can show up in real estate as well. We see it in home appraisals.

Some of the most heartbreaking stuff that I hear is a couple of Black folks who want to sell their homes feel like they have to scrub their homes of any evidence of its race or the occupant’s race to get the maximum appraisal value. There’s evidence of this happening in multiple parts of this country. That is not just happening here in Ohio or Florida. It’s happening all over the country, which shows you there’s something systemic.

If it’s the case that a home can be appraised on multiple occasions if at one time it has evidence of a Black family there and another time it has evidence of a White family living there when the evidence of the White family living is there, the appraisal comes in higher. Is it the same house? What else is that? That’s why I struggle with people. I’m like, “What else do you need to see to recognize that this is a real and salient issue?” If you can focus on the fact of this existence, we can focus on how we dismantle it.

When you compound this over time and you have, by definition, that systemic effect, then you are driving this further down this path, which then makes it much harder to reverse and interfere with. Dax, as transformative leaders and drivers of change, our motivations are often grounded in a set of values or principles.

In the Special Operations in the Talent War Group, our guiding principles, our values or what we call the characteristics of elite performance are drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, curiosity, team ability, effective intelligence and emotional strength. There are nine of them. You have a core set of beliefs or practices that serve as your guiding principles, what motivates you to wake up every day and continue to push this conversation forward? Those are bravery, community history, honesty, humility, integrity and story.

There are seven of them. These closely correlate to these nine Special Operations Forces’ performance. If you would, I want to go down this road and dig into the conversation about the racial divide through the lens of these values and your values. Tie them into the nine. This is what we are fighting for. We are fighting to be a value-driven society of people who want to be good to people and do the right thing.

The goal of the show is to create a community of elite performers across all races and industries. I don’t care who you are or what you do. Can you be better tomorrow than you are today, yourself, your team and your organization? That collectively, do we drive society forward? That’s what we are doing but it starts with the values.

Let’s start with bravery. You have defined bravery as, “We believe in facing each other, ourselves and that which divides and discomforts us. We strive to create and hold space so that we can be and remain brave in each other’s presence.” I call it to drive and emotional strength. Drive, the need for achievement, a growth mindset, be better tomorrow than we are today and continue self-improvement to force ourselves to be uncomfortable. If we are not uncomfortable, we can’t grow. Emotional strength, do we have the courage to remain calm in stressful situations, to push ourselves to act responsibly when we want to turn the other way? Can we push forward?

You said in the book, “I understand the layers and divides in a way that gave me insight into the tensions within. I knew how the average privileged White person who sat on boards and led nonprofits had been educated around race. I was educated right alongside them. That education had left out a critical context. It led us to falsely believe that racism was a minor problem that had by and large been solved or that it was too big and not worth tackling at all. It was important to my own healing that I challenged myself and my clients to be brave with one another. White people, especially White men, are being asked to give up the reins even as they are still being called upon to commit resources.”

We have spoken in previous episodes about what we call limiting beliefs, institutionalized thought about societal problems in which a single person stops themselves from action because the problem is too hard. “Someone else will solve it. Even if they try, it’s not going to make an impact so focus elsewhere and do something else. Don’t bother.”

Author Colin Beavan in episode fifteen said, “We have to have the courage. Can you as an individual have the courage to try even if it doesn’t go anywhere? What if it does? Can you then look inward and say, ‘At least I tried?’ If it does go somewhere, do you then create a movement because the movement starts with one person?” Can you talk a little bit more about the conversation?

You spoke about some periods and referenced some legislation in the past. This is emotionally charged. There is a decision point that we are at in society. You spoke about legislation that set the conditions for the next 30 years. That’s where we are. If we don’t do something, it’s going to get left behind. We are going to forget about it. Where are we going to be in 5, 10, 20 years? Why now? In the past, why have we been so quick to dismiss the conversation and accept the status quo instead of doing something about it?

I’m reading a powerful book called the Unworthy Republic by Claudio Saunt. It’s a story. It’s a book. It’s an incredibly detailed, rich and meticulously researched story of the dispossession of Indians, native folks in the 18th and the 19th century. He goes through a painstaking process of helping you understand how, in particular, the Indian Removal Act came about and executed. Also, how systematically the combination of Wall Street and the Planter Class in the South were able to expropriate and dispossess native peoples of their lands, and then financially benefit from all of that.

A key feature of doing that work is applicable in many ways. Enslaved Black people were part of that narrative because they were property that was also being bought in the open market. That money was being facilitated through Wall Street. It was running and flowing through these banks through capitalization. It was all part and parcel.

What fundamentally allows for that to happen is there are certain beliefs about other human beings. I have to believe and be convinced of the belief of a racial hierarchy for me to subjugate other human beings to something I know I would never allow to happen to myself or anyone that I love. To dispossess native peoples of their lands, I have to come up with an entire ideology that suggests this land was put here for me to put to use and these people are not putting it to use.

Part and parcel in the way I can do this are by framing them as savages and uncivilized. Likewise, to be able to rationalize a system in which we are going to strip people of their families, separate them across the country and use them as our labor for all manner of things, I have to have an ideology that supports that.

Cognitive dissonance is a real thing. I still need to be able to call myself a Christian, to say I’m a good person, a good member of society and a sinned member of my community. To facilitate that, I have to be able to both believe myself and engage with others of my ilk in a set of beliefs and practices that hold this group of people not only as inferior but as subhuman.

To me, part of what I’m trying to help people think about is the extent to which those ideas continue to permeate our culture because they were so foundational. This is why we are seeing this pushback around critical race theory and this desire not to have these conversations. When we peel back these layers, we start to see how it was a foundational set of beliefs that were necessary for the building of a republic that we, in many ways, are benefiting from this. I’m sitting here and benefiting from this in many ways as well.

The courage and the bravery component I talk about is being able to face and understand that history. It is not just something that happened in an episodic way. It was a fundamental feature. Generational wealth was generated. At one point, Saunt talks about in his book that roughly the value of slaves in the South in the early 1830s was about $700 million, $10 million, $18 million and $30 million. That’s roughly the equivalent of about $20 billion some. That’s probably an underestimate. Thinking about and processing that amount of wealth that was being trafficked and that human trafficking that was taking place.

That’s a value on a race of people.

It’s still dehumanizing, disgusting and disheartening.

You can’t even put a value on it nor should you.

We could qualify that and should name that but that’s what was happening. Nevertheless, that is still an ethos that continues to have some penetration and some value in our society such that you have communities in which are predominantly Black. In our culture, in our society, there’s a supposition that the land there is less valuable because Black people, Brown people or non-White people are there.

When White people come into a community, into a place like DC and they returned in the late ‘90s and 2000s with gentrification happens, you see property values escalate. For us to not be able to have a discourse about how that is linked to a history of racial hierarchy, a history of subjugation and a history of devaluation of the body of Black and Brown people is disingenuous. It’s cowardice because it does not allow us to deconstruct that and reconstruct our society to something that we all would love and would allow us to live into our values more.

Let’s talk more about history, which is another one of your values. It’s the second one. You said, “We believe human-constructed structures and systems have created barriers and boosts that have held some of us back and propelled others of us forward. We also believe our attitudes and ideas have been shaped by what has and has not happened to us. We strive to visibilize and validate the unseen phenomenon that is at play all around us and shaping our shared experience.” I would call this effective intelligence, applying one’s own experience and knowledge to the situation. Our past experiences shape our decision-making and our perspective.

You said as well, “We have been at this crossroads before. White Americans, your parents and your grandparents also watched in horror as cities burned. They also awakened to Black anger, pain and promised to do better. Our entire history is littered with examples of the White power structure responding to Black unrest through actions deemed appropriate and acceptable to the White majority. The options presented by Black people themselves are never seriously considered.” You have referenced President Nixon, President Johnson, affirmative action and multiple Supreme Court cases. You talked about them in reference in the book. Have we learned anything from history? Are we on a path to continue to repeat it?

Let’s be clear. All of our lives are a demonstration of progress. Is it progress in the way that we think of a pure straight upward trajectory? No. It’s jagged progress. It’s two steps forward and one step back. I would be doing a huge disservice to my ancestors to sit here and say that my life has not been, in many ways, benefited from and as a result of the struggle of Black people, White people, Latinx community. There has been a struggle that has created the conditions for me to be sitting across from you, you sitting across from me and us having this conversation. I want to name that and be clear.

I would never say that there’s not progress. I believe in progress. We have improved in many ways. I also understand that we, as human beings specifically, in America, have patterns of behavior. Our patterns of behavior seem to indicate to me that if you look at reconstruction, even as another example if we look at what has been deemed too much progress by Black people, not all White people but there are members of the “White race” who become very agitated and disturbed by that. There’s a belief that they have that, this is their country. The notion that Black people are getting ahead in some way is disorienting because it means that in some way, in their minds, they are falling behind.

I suggest that that’s a problem with binary thinking and a scarcity mentality, a notion that there’s not enough to go around when there’s plenty of lands and resources. There are lots enough for everybody but we still have this notion that there’s a limited supply, limited X, Y and Z. Therefore, we are putting ourselves into this perpetual competition. As long as that perpetual competition for what are considered these coveted few spots for whatever they might be, we are going to find ourselves in this oscillating historical trend of forward and backward.

Every time we have unrest, the unrest leads to moments of conciliation. The conciliations happen for some time, and then people feel like, “We have done enough conciliation. We have given enough to Black people. We have listened to their complaints and concerns. Let’s get back to business.” That means, “Let’s reassert hegemony, our authority, and our supremacy in some way, shape or form.” That leads us back into another cycle.

In the ‘60s, we saw the upswing, which then you follow up with the prison crisis and mass incarceration. We see the stripping away of public policies and praying. The Great Society is stripped away bit by bit because there’s a framing nationally that the problem is too many people are getting handouts. We never can have a sustained conversation about dispute wealth and equality, and the need to radically rethink how we distribute wealth in our society.

We always have this tendency to focus our attention on these people who are getting some extra crumbs that they have not earned and don’t deserve. We lose focus. That loss of focus leads to backsliding, backlash, anger, and resentment that then puts us back into this quagmire all over again. We find years from now, there’s going to be another social unrest moment, and then they are going to be looking at us like, “What the hell were you all doing? Why are we here again? Why didn’t you all finish the job? Why didn’t you stay focused on what it was?” We are going to be like, “Because of X, Y and Z.”

We have to understand that our tendency as a culture is to lose focus on this issue. At least in my view, it’s because we have still fundamentally not reckoned with how we want to organize ourselves as a society and how we want to understand who we are. Not just this nation that is built by and for White people but it has been built by and for many different kinds of people from many different backgrounds. Chinese folks built railroads. It’s who we are and that’s troubling.

We had the census results revealed. It was disturbing for some people to see that the “White race” is losing ground if you will because you have the stark increase in people who identify as Hispanic, as Asian. You even have an uptick in Black and African American people. As long as we have this notion of us and them, whose land this is, who founded this place, who built this place and it’s built upon and built against these myths that are inaccurate and patently untrue, we are going to find ourselves constantly in these struggles.

That brings us to the community. You have defined community as, “We believe people in proximity and relationship can solve their own problems. We strive to create and maintain the common ground for genuine community building.” That’s your definition. I’m laughing only because this comes up that everybody thinks we get so much done and we are productive when we are on our phones, computers and Zoom calls.

The reality is you achieve much more when you sit in the room with a person. We have demonstrated that here in the day we have spent together. You can’t replicate that when you are in different places and you are not willing to come together and have a conversation, this certainly is at the most macro scale. We call it team ability. The aggregate is greater than the individual parts.

Can we work as a cohesive unit towards this winning goal? This battle is not going to be won by Black or White people alone. This has to be won together. It has to be this team that is built. Everybody collectively says, “We are all in it together.” To drive societal and generational change, it’s an all-hands-on-deck approach. In the context of building community, you have cautioned against one societal norm, charity. Charity is a divisive topic. I agree with you on the fact that it is a divisive topic.

You said in the book, “I learned that charity culture treats the symptoms but not the disease of racism, obscuring the role that policies benefiting the wealthy, tax cuts, tax credits, privatization and deregulation play in maintaining racial inequality. The culture does this. Even charities themselves exploit racialized symbols, stories and stereotypes to fuel their missions. The annual fundraiser is where it all comes together in what can only be described as an ensemble celebration of White Saviorism no matter how seemingly diverse or inclusive.” Can you speak more about the roots of racism, the symptoms, and the mechanisms that we can use to identify these roots and attack them? We all agree that charities have a place. How do we leverage them in the right way?

There are a couple of things happening. To go back and think about the nineteenth century, it is the case that there were leading abolitionists in New York whose wealth had been built off of the slave trade. It is the case that leading philanthropists of the day and their wives who were involved in any number of charitable endeavors, abolition being one of those.

Women suffered being others. Their husbands were the main ones setting up these companies that were designed to dispossess the native people of their land. Charity fills this gap. It does this work of standing in as a band-aid in a bomb that’s supposed to, in some way, lessen the suffering that people are experiencing through dispossession, expropriation, violence, and other means of subjugation and oppression.

Even from a tax code perspective, charities were set up out of the tax code as a means by which to hold and maintain wealth. That’s part of what they can do. If you look at any number of foundations, it’s part of why you see a lot of wealthy people set up foundations. It’s a way to pass on wealth generationally through a minimal tax structure. You can exert tremendous influence through foundations, whether it’s the ideas that you value or the issues that you care about. There’s one way to do so.

Largely, these are public dollars that have been rerouted into private hands. At least in the modern-day, in our lifetimes, we can trace it back to the early 1980s when you saw a radical change to our tax policy such that it created a class of wealth that we had never seen in this country before. We continue to see that we can create a whole infrastructure to execute the ideas that they care about and push the issues that they want to see pushed.

Charities begin to pop up more and more to begin as the executors of these visions if you will. These are not the problems of individual philanthropists to solve. These are societal problems that we should be solving as a society. That is why you have a government. That is the purpose and my view of a large government. People might want a small government. I know there’s the bureaucracy involved and it’s an imperfect structure. I’m much less bullish if you will on the notion that a venture capitalist, a hedge fund manager or whoever it is should be the one telling us how our society should be organized and how change should happen.

What you often find is that people don’t have a deep engagement with how poverty even exists in our country in the first place that it is, in many ways, structural. Why do you have so many people living in generational poverty? If you are born into poverty, the likelihood is that you will live in poverty, die in poverty and your children will live and die in poverty. Why is that the case? There’s a structural feature to that. As wealth begets wealth, poverty begets poverty.

That has something to do with our policies, our choices and how we fund schools. We do know our tax code, our tax policies and local taxes, fund schools. I spent a lot of time in New Jersey. I went to college there. Going from one school district to the next or one city to the next, you can see how tax policy is driving the quality of education. If we know this, then why haven’t we addressed it? It’s because we don’t want to. We are fine with it. Therefore, we are fine with having charity step in because the charity can make us feel a little bit better about it.

We can help a couple of people but we are not fundamentally changing anything. We can help those that are worthy. The exceptional Black kid who does well and who comes to the program that I wanted to come to, we can help that kid. What about the disaffected one and maybe doesn’t have any belief and/or is disengaged from? We can’t do anything with that one. We are not going to fundamentally address what’s happening in that community. We are not going to fundamentally address how that family has been broken or how his parents have never had opportunities.

We are going to be myopic in our focus on how we are going to address these things. I know that charity does good work. It’s hard for me to be critical of something that I have participated in and know has value in our society. In many ways, we have set it up as a savior of a problem. It’s alone to solve and it needs to be addressed as a societal problem and not be focused on and dressed as a problem of individuals, institutions, philanthropists or foundations. We can’t expect them.

The last thing I will say on this is if you look at a foundation, the law only requires a foundation to spend 4% of its corpus on an annual basis. That’s crazy. That sets up a cycle of perpetuating its own existence rather than using the money in this corpus to solve a problem. It creates the condition for people to spend as little as possible, 4%. It allows you to keep going, moving, and existing in perpetuity as if you are solving this larger problem. I’m like, “You could decide that you’ve got to spend 50% of the year.” He’s going to go out of business in ten years and that’s what it is. We will try to solve the problem.

We can go hard and try to do it but we don’t want to do that. We would rather do this small stuff, these little things. We then get into this celebratory moment when we have one kid or a group of young people who can get ahead. That doesn’t change the underlying problem. I want to change the underlying problem. I want to change the underlying system that is rigged.

Identifying the underlying problem requires another one of your principal values, which is honesty. You have defined it as, “We believe in truth-telling and seeking. We strive to center our words and actions and those with whom we partner in truthfulness.” We call it integrity. Do what’s legal. Do what’s right. Be a good person. Tell the truth.

You said in the book, “If we are going to survive together, you will not be able to decide for everyone else how society shall function. The only way that you will be able to embrace our new shared reality is if you can come to believe it’s best for everyone including you. I have been in conversation with dozens of White men from different walks who are awakening to the realization that maybe simply not being a racist isn’t enough to end racism.

These men want deeper insight into not only how racism has harmed Black people but, for the first time, into how it has harmed them. They are beginning to see that racism warps us all. The maladies merely manifest differently on the dominant group than the subordinates.” You spoke a little bit about the dominant group versus the subordinate. This is an important concept. Can you explain that a little bit more? Also, how does the perspective of the dominant versus subordinate affect both sides in the conversation of racism?

I credit Beverly Daniel Tatum, she was gracious to do a blurb for my book for helping me think about the language of dominance and subordinate. She wrote an essay that I often use in my work and I talked about in the book a little bit as well, around dominance and subordinates. Fundamentally, she gives this powerful example in the classroom whenever she asks a student to write down their various identities. She notices that White students never identify White as a part of their identity but students of color will. She will notice that men are less likely to identify being a man as a part of their identity, as women who will identify as a woman, as a part of their identity.

Dominant in subordinate functions across all of our identities. I hold some dominant identities. In fact, I’m a man in our society that is male-oriented and is a patriarchal society. I am an able-bodied human being in a society that caters to people who are able-bodied. Meaning, I can move through the world and do all the things I want to do. If there’s not an elevator and there are some steps, I’m good. I don’t worry about those things. There are a lot of that. I am educated.

I have a fairly decent education in a society that values education and those who don’t have it are trapped and locked out of opportunities. I could go on and on, and talk about the various identities that I might hold that also give me some dominance in society. Race, being such a central feature of our history and experience is, I would argue, probably the main fulcrum through, which dominants and subordinates continue to be experienced in our society.

It’s such that one who is a member of that group doesn’t have to consciously think of themselves as a member of that group to accrue the benefits that are associated with that identity. I don’t have to think about being a man and constantly walk through the world, as such, to accrue some of the benefits that are a result of a male dominant society.

When I open my mouth, in meetings in certain spaces, people will listen to me differently because I’m a man and it is assumed that I had this education. Likewise, our history is rife with examples of, not doing the political thing but we saw the president of our country, who holds the highest office in our country. In many ways, had he been a man of a different race, A) he would not have gotten into that position. There’s no argument about that. B) The mere fact of the president who preceded Obama, the level of perfection he had to reach to be considered a viable option for the same position gives me a clear indication about how dominance in subordinates is experienced through the lens of race in our society. You ask the second part of the question.

You define that in the book, too. It’s an important point that we need to bring up here. You have quoted what you have called the perfect Black man. Would you define that and go into that because you bring up a strong point?

It’s the case for anybody who’s not part of the dominant hegemonic society, the order in our society. If you are not a Whitecist presenting man, you will more likely be going to need to have a set of credentials that are associated with the institutions and accolades. Also, accomplishments that White men typically have to be perceived as being equivalent to another White man who may not even have those credentials.

You talk about Obama as an example. He’s an aberration. He is an amazing human being. He’s done some amazing things but to use him as the example of we are doing well, this trope has been blown out of the water, is problematic. What we are suggesting there is that to be considered qualified for this job, we have not required others to have these levels of credentials, the right family structure, the right look and the right kit. Everything has to be right for you to get ahead in this society. I was socialized to understand that.

Growing up, I knew that my margin for error was narrow. I couldn’t have blemishes that maybe my White counterpart could have on my record. I had to be unimpeachable. I resisted that. In many ways, I didn’t even live up to what that might have looked like but I do understand that. That’s why I cringe in our society, for instance, when we put so much value on somebody having gone to Harvard, Yale or having had certain experiences and some think tank or some other institution. I’m like, “What we are implicitly saying is that the only people qualified to hold any power or authority in our society are people who have gone through those particular institutional structures. Anybody who has gotten any different kinds of experience that could benefit us as a society is less valued.”

There was a statistic done in the Biden White House. Forty percent of the people there are Ivy League grads. Why is it the case that our government has to be highly populated by such a small cadre of people who have such a similar experience? Why don’t we open it up? That’s doubly or triply the case for people of color. For me to be perceived by you, not you, as an individual but as having competence, I need to have a resume that meets your approval. By that, it means I have to have gone through the institutions that this society has sought and decided are the most esteemed, elite and valuable to be associated with.

To me, that’s troubling because it suggests that at least up to now if I choose to go to Howard or Florida A&M or North Carolina A&T or any Black HBCU, it would be perceived as if I’m inferior because I went to an inferior institution. Stacey Abrams is a perfect example of that. She’s an HBCU grad, we do see a lot of Black leaders in this country at this time. I want us to be able to open up our thinking about what our possibilities are in who could be a leader. Who could be someone that we can listen to and follow? It doesn’t need to be coming. They will have to all come through the same conveyor belt for us to deem them qualified.

There’s an argument to be made there too about diversity. In the diversity conversation, people say, “We have to have diversity.” They default to, “We need to have a White population, Black population or an Asia population in the office,” but they all went to Harvard. Everybody looks different but they all think the same. Have we created a diversity of thought in this organization when we are all going to sit here and agree with each other? We just happen to look different.

I always argue that any work in the equity space needs to start with the E and not the D because of equity and inclusion drive diversity. Diversity is an outcome. You get diversity when you create more equity. Creating more equity means you look at your policies, practices and say, “Are our policies and practices implicit or explicit? Are they set up only to allow into our community those who don’t look like this externally but have the same experiences as us?” Have we created an environment where people who might have different norms or whatever else might have you can thrive here as well? Have we created an environment where only people who have been socialized in a certain way, follow a certain structure and rule to survive here?

That’s why I suggest that when people want to make a change, you don’t start with, “How do we get new people, different colored people or different races in this room?” It’s, “How do we look at our existing policies, practices, systems and structures?” Ask ourselves the hard questions about, “Why do we have these? Are these serving us? Do we want equity? Do we want differences or do we want to cap superficial differences so we can check that box and keep it moving otherwise because we don’t think there’s any problem with the way we are doing it?”

We will go back into humility here because this is where I wanted to go with. In the humility piece, which you have said that we believe that no one has all the answers and we strive to listen more than we speak. We call humility, which is also one of ours in that kind, recognition that we don’t have all the answers. We have to be willing learners, we have to maintain accurate self-awareness, seek other’s input and feedback to make educated decisions.

You spoke in the book and your consulting that you found that in the vast majority of cases, leaders, their intentions were earnest. They wanted to do the right thing. They wanted to listen to their staff. When they look around, there are no people of color right in the actual organization so they have to go out and find them.

You also said that the answer to systemic racism is not simply hiring more Black people and looking at the newly hired Black people and saying, “Go solve the diversity problem in the organization.” You said, “We both need to accept that we have failed in moments of great possibility in our past because we begin the journey with different agendas.” My question is and we have talked about it a little bit here, how do we set the tone for this in the organization because I always assume it has to come from the top?

I have the benefit of working with some organizations and a common challenge I see that people have is language misalignment. We might use the same word and have different meanings for that word because we haven’t calibrated collectively in such a way that we are clear about what we are up to and that is the leader’s job. Unfortunately, what I find is that, quite often, it’s the case that leaders are uncomfortable being clear, direct, and careful in the articulation of both the problem they are trying to solve and the commitments they are going to make to the organization for them to solve it.

Quite often, I hear platitudes and broad statements that can be interpreted in many different ways. I hear a tepid commitment because underlying there, there’s still some reservation around, “How’s this going to play for this community? How’s it going to be this and this?” They are still leading through a consensus in their mind and that’s what we do see a lot of people, unfortunately.

I have encountered that there’s an assumption that what it means to be a good leader is to not be the person who makes definitive statements, to not be the person who is a person being perceived as having a strong voice. I find a lot of leaders have imbibed this belief of, “I should allow the process to play out. I should defer and give authority over to X, Y and Z.” I’m like, “You can do that but you have to set the tone already.” It’s an order of operations. You can’t give over the power or say, “I’m going to leave it to the people to do it.”

What ends up happening is all the people in the middle are confused. Those are all those middle managers. In every organization that I go to, middle managers are drowning. I’m getting messages from below and messages from above. I don’t even know how to reconcile them. If I could get clarity from my leader and what they are trying to say, I can either push it or resist it. I’m getting uncertain, therefore, I’m left to my own devices and I’m going to create my own reality if I have to and it’s necessary because I have to survive in this uncertainty.

I do put that on leaders. It might be unpopular, as a matter of fact, to say, “We are going to focus on this. We are going to move these numbers for the next five years and we are going to keep our attention on it.” Some people are going to be upset about it. Some people are going to be like, “Why are you not focusing on women? Why are you not focusing on this community?” You have to be able to have a story for why.

Those are good points. You do see that a lot in these situations. You call it stepping up. Cleo Stiller, in episode seven, where we spoke about the meteor environment, called it Stepping Up. As leaders in these situations, can we look ourselves in the mirror and say, “I have to take a stand here. I’m not going to be able to sit on the fence.” You do also run the risk of becoming inauthentic at that point as well.

What I am encountering is what has allowed and I will not say a lot because I have met and worked with some amazing leaders, some people have risen into their positions of authority, A) without this as a competence, without having any competency in the area of cultural awareness. B) Some people have risen by not waking waves. What I find unsettling and I have experienced is when I had an opportunity to work with some senior leadership teams. This is definitely not the case in all instances. I have had some strong experiences. I have watched bad actor CEOs make aggressively ignorant statements in their 2nd, 3rd, and all those people that sit there.

I have watched them make insensitive statements and I’m like, “This is how you get ahead here. You get ahead in this environment and these people are in these senior positions because they have not made waves. They know that it’s too much of a risk to challenge leadership even if it’s done tactfully and done in a way that can be respectful so I’m going to be quiet.” That’s the culture here.

That’s a problem, especially when it comes to issues around diversity and, especially when we come to issues around race because a lot of leaders I have encountered still harbor an underlying belief that systemic racism is not the issue. It’s a competency issue that Black people aren’t smart enough, don’t work hard enough, have not tried hard enough. That’s the problem. Efforts that are designed to address past harm are efforts that are going to lower quality or create tokenization.

Until we get people to be brave and honest about what their actual feelings are, what they believe in, we are going to find ourselves in these superficial spaces where you have lots of employees saying, “The D and I efforts are a failure. They are a waste of time. They don’t do anything. Why are you bothering?” It’s self-fulfilling. If you have never committed and if you begin the journey believing that there’s not a problem to solve and you are only doing it because the culture out there is so woke and, “I have to do this so let me do it.” If that’s your starting point, of course, you are going to see failure. You are not going to move the needle.

If you believe there has been some deep harm that has been done in this country and it’s inescapable, unavoidable, undeniable and even if I don’t fully understand how it’s happened, I’m committed to making sure it’s not happening here. Even if that means I have to listen to people who I have not listened to in the past, take some leadership from people who might have more insight into these issues than I do, I’m willing to do that. I have met some leaders who are that way, too. It’s exciting to be in those rooms with those people, because it’s like, “She gets it. He gets it. They are going to be alright.”

You open the door to the next value, which is what you are calling inquiry. We would call it curiosity and this belief that the only way to get answers is by asking questions. We call it questioning the status quo and pursuit of better. We have to have continuous growth, attitude and we have got to learn more. If you are a leader and you have to build this program, you have to listen to everyone. The only way you become an authentic listener is to have a genuine interest in what you are trying to find out. If you don’t care, you are never going to get there, as you identified.

You have framed this and you have thrown out a lot of questions, which you have referenced. I would agree with you that these are difficult questions to ask as a leader in an organization trying to develop a program like this. It starts with, as you phrased it, “Does the policy protect rights that Black people are unable to access because of racism? Does it preserve privileges that were only available to certain groups of people based on their racial classification?”

You have taken it a step further and you said, “We have to ask ourselves questions. We have to look inward and think about our beliefs, where and when were they foreign? What happened? Who was involved? Was I a bystander? Was I a victim? Was I the perpetrator? Was I silent? Did I turn away? What did I learn in that instance? Did I learn anything? Did I stop to think about it? Who was involved?”

There are these questions that you are drawing out of people in these instances, whether they be the CEO who makes the off-color remark and everybody else sits there. Your challenge to them is, number one, show integrity and honesty. Number two, ask the question, “Why am I sitting here accepting this?”

“Why is this okay?”

How do we change that second level, that mid-management, that person in line to be the CEO who thinks, “If I don’t tell him or she is wrong, then I’m going to get fired?”

There’s got to be some incentive associated with it, too. People are motivated by risk and reward. They are motivated in that way so we have to tap into that. Incentivize people to push to challenge. We have to teach people how to do it in a way that is tactful and productive in a way that’s going to keep the conversation going.

One of the things people have maybe responded to about my approach is that even though the book is hard, pushes and challenges, it doesn’t feel like it’s self-righteous. Part of the why behind that is experience. I offer my own experience as a way to demonstrate vulnerability and that’s the key right there.

Part of the question, the inquiry, the process, the project, and the practice that I’m getting at is that leaders have traditionally been trained to be stoic, to be opaque, to not offer too much of themselves because that means it creates vulnerability. That vulnerability can be used against you and that might demonstrate weakness. If we think about them, there are a lot of male-identified norms and values that are infused in our notions of what leadership looks like.

It’s called the Man Box. Cleo Stiller called it the Man Box, “I have to be tough. I can’t show emotion.”

At this point, what’s exciting is, that’s being challenged. We are seeing people who recognize that vulnerability is a strength and an asset. You and I were talking about younger people, Generation Z and Millennials. That’s an expectation that people have of their leaders. I want to know who you are and who you really are. It’s not so that I necessarily can use it against you because I want to make sure I want to connect with you.

If I look at the leaders that I have admired, connected to, aspire, and in some way, emulate, it’s how they respond under pressure. All those things are valuable expressions and manifestations of leadership but a lot of it also is vulnerability. Can you say, “I’m wrong? I missed that one right there.” Acknowledge somebody else when they are right or when they make an excellent point. Can you lift people up in a way that might even mean that you get knocked down a peg? All of those things are such central features for us. I know we are having this conversation.

We look at our climate crisis, COVID crisis and our racial justice crisis. All these things are going to need to be dealt with through the lens of vulnerability, the ability to express empathy and demonstrate model empathy. Can you tell a story about yourself as part of this journey, as part of this work? I don’t want to hear about your successes. I don’t think that’s what people want to hear. I can read that in biography but what I want to know is how you navigate your shortcomings and how you build against those.

The story is your last value. You believe everyone has a story. Once we bear witness to that story, then it creates a bond. I agree with you. I love telling stories. That’s probably why I wanted to do this show. I would tie in here from the perspective of the nine characteristics of elite performance, adaptability and resilience. In your story, it’s what creates you and there has to be a reaction and a change to the changing dynamics of a situation but then also, perseverance in the face of challenges, as you talked about. You talked about a lot of different stories in the book. You mentioned some of them here.

There’s a story you tell in the book about you being arrested after your friend did a pull-up on a piece of scaffolding, which was a defining moment for you. I’m wondering if you would be willing to briefly share that story and what that brought to light for you about this argument of systemic racism because it shaped you. Also, not only yourself because you handled it one way. I’m not telling the story here because it’s your story and you deserve to tell it. It should be told by you. your friend’s life went drastically different because he pursued a different direction than you did. I’m wondering if you can tell it quickly and give that synopsis.

It’s funny because we are not far from where it happened. As a matter of fact, there’s a story I could tell you 200 feet from the building you and I are sitting in. When I was eighteen years old, that was the first time a cop put a gun to my neck. I graduated high school and was a teenager in a McDonald’s that’s right across the street. I’m hanging out with my buddies and ended up in a situation where a DC police officer was putting his gun in my throat.

I trust and believe that I was no threat to this person. I had no weapons and I had nothing to do. I won’t get into that story but I will point out that the one in the story is important because I was in law school at the point in time in which I found myself in jail. I found myself in a jail cell for several days. I experienced police abuse, got beat up with batons, saw my buddy getting beat up in broad daylight while people watched.

No one did anything and I didn’t expect anybody would do anything. It was shocking for folks to see this happening in front of their eyes. In many ways, we were two young Black dudes. I was in my twenties and I’m sure that there was probably some belief in people’s minds that we had done something to deserve it. It was a pull-up that my buddy did on a scaffold and that precipitated our unwillingness to get down on our knees and submit to unjust authority at that moment.

I share that story because it did give me an opportunity even as I was in law school to have to be processed through the system. You see how once one is processed through the system. The moment you are in, you are suffused in uncertainty. You don’t know how this process is going to unfold and you realize how limited your rights are about law enforcement in the structure that you are operating against. Everything is, in many ways organized to support their narrative, their framing of it.

They are the ones that get to file the charges and they can file a charge saying that I initiated this altercation and therefore charge me with assaulting a police officer in many ways to cover up the fact that we have been abused. I have done a lot of research that’s separate from this but it is common for police reports and arrest reports to have a couple of different charges that are often on there, especially if they are altercations. Assaulting police officers is always there so does disorderly conduct or obstruction of justice.

They run in threes. At least 2 out of 3, you are always going to see them because that is how law enforcement sets up its own defense. Now they have a bargaining chip to use against you because they can then come to you and say, “We can work with you. We will lessen this charge,” which is a bogus charge anyway. They are like, “We will lessen this charge,” and you are more willing to negotiate against that.

For me, from that point going through the jailing system to going to central booking and seeing yourself inside of this huge cage with 100 and some other dudes who had been in a cage for a couple of days. I was put into another cage, squished into a cage with 50 other people. You are given this terrible lawyer who doesn’t know anything about your case. You are brought before a judge, arraigned, thrown out back out in the street bewildered after days in the darkness and your life has been radically altered for at least the time being.

You’ve got to get a lawyer. I’ve got to pay thousands of dollars for this lawyer to defend something I didn’t even do. If I didn’t have the resources, then I’m up craps creek at that point. You show up to the courthouse and you see young Black men being cycled through this whole thing standing outside with judges on the elevators. This whole apparatus is the modern-day cotton field. This is the rice field. Whatever field it was centuries ago, it is this now. We need to be clear that that’s what it is.

Everybody in that building is getting paid. The guy shining shoes is getting paid off of me being here. The clerk who’s putting a stamp on the document that’s going to have been filed away is getting paid off of this. This is a cyclical thing. The criminal justice system is the most physical manifestation of the way systemic oppression operates.

People will argue that it can happen to anybody. I’m sure it does and it could but it’s the desire in the designs of the police and law enforcement industry or structure that focuses its attention on certain communities and bodies. As I put out in the book, I highly doubt two of my White classmates standing on that same corner in Adams Morgan and if one of them did a pull-up, a cop would have pulled up to them and said, “Get down on your knees.” If we are going, to be honest with each other, we have to know that would not have happened the same way.

The criminal justice system is one system but the healthcare system also has manifestations. The education system has manifestations of these things. These things have vestiges because they were part of how they were formed, developed and created, and were in many ways built around a notion of who is valuable and who is not. Who are we here to serve and who do we hit extract from? Who are we here to exploit and who are we here to protect?

If that was foundational and we have never gone back to restructure the thing, even if it’s not explicit, it’s still finding a way to weave itself in there and live inside of this the expression of the thing. What if we were two White guys, would people who are going out to dinner stand there? I watched people walk by and not even pay attention to my buddy getting beat in the street corner.

There’s a numbing that happens to us around violence to Black bodies. That’s when I say the harm goes both ways. If you can walk or see Black pain and people are violent against a Black body and your brain goes, “What did they do wrong?” You then need to check yourself. Understand that it is an unhealthy response to someone who is suffering to ask what they did wrong to deserve that.

If you automatically go in your side with the people who already have the state authority behind them, have a license to operate a weapon and have an entire infrastructure to support their narrative. If you automatically go to their side every single time and you never consider that there might be counter-narratives here that we need to take into consideration, maybe you have a warped idea and sense of how society operates. It’s unfathomable to me because I have had to live in this body all my life and had to therefore develop some way to make sense of it all.

If I didn’t develop a way to make sense of it all, I would go crazy or I would believe what’s put out there for me to believe about myself. We have to create counter-narratives. For me, that was the experience. I was thinking about writing about that one because I don’t want to engage in what’s called the idea of the reproduction of Black violence and Black pain. I don’t want to engage in this pornographic idea of how we see Black pain in our public sphere.

I thought that there was something instructive. As you pointed out, my best friend at the time, he and I went through this exact same experience together. I make a decision, ultimately, that I’m going to cop this plea if you will if I’m being honest about it because I’m getting offered what is an opportunity to get back to my life and my buddy decides that he’s not going to do that. He’s going to fight this thing.

Unfortunately, I watched and I can see his causation but I saw a correlation between his fight and mental deterioration that he never fully recovered from. It’s heartbreaking because he’s a genius and he is one of the best human beings I have ever known in my life and to watch that experience strip away something so fundamental to him that he could never regain again. You could say he should bounce back from it but everybody can’t just bounce back from these kinds of things.

It’s not fair to say they should just get over it, bounce back and figure it out. You do it. You bounce back. You have yourself beaten into an alley and you have your rights stripped from you in a snap of a finger and told to have to cycle through a system. You bounce back and think everything is okay. Not everybody can do that. I was fortunate enough that I had family and I had whatever those things allowed me to do it but even as I sit here talking to you, I still get sweat into my arms because I’m still back on that street corner. I can still feel it, see it, and know that it was a real thing that happened in my life.

It affects you. It shapes you. I’m glad you told the story. Thank you for sharing it here. I can see it in you and the emotion that it brings. I get down your stand.

I remember writing a story about that experience and submitting it to every newspaper and nobody cared. Do you know how heartbreaking that was? I thought maybe because I was a Law student but no one cared. Not a callback, not a write back, nothing. When I see all this hand-wringing but newsrooms and journalism didn’t care for a long time when people were telling these stories because we were numb to it. No one thought it was a story.

Where do we go from here? We’ve got to start this process of internalization. We as leaders of organizations have to make a change but we can’t just hand way that. We can’t check the box. We can’t say, “I instituted a DEI program and everybody took the twenty-minute online training that they clicked through and they passed the ten-question test. Now, everybody in my organization knows what racial profiling is so we are good to go.” You used a framework in your consulting practice that you have highlighted called LENS. Listen, Empathize, Notice, Speak. Can you talk about this framework? This is what sets you apart from others. You’ve got to put it one step in front of the other on this thing. It has to be meaningful.

Our tendency in this country is to start with speaking. We see people talking all the time and don’t know what they are talking about. I have had people critique my work and I’m like, “You don’t even read the book so what are you talking about? You haven’t cracked it.” Before the book even came out, I had people who are like, “Who is this guy? You are just depending on this whole thing.” I was like, “You haven’t even read it. How do you have that strong of an opinion about this?”

There’s intentionality the same way I structured the book. There’s a section about harm, heal and then act because we want to go to action right away. Companies that want to just act right away, “We are ready to go. We are ready to do it.” Why weren’t you ready a year ago? What makes you ready now? It’s because you say you are ready now, you are ready? That’s why I start with. What kind of learning have you done? What kind of listening have you done? Listening can happen and manifest in a number of ways.

I am of a belief that listening does begin to help us connect with the empathy that’s going to be necessary to do this work. Empathy is such a critical component to leadership but also specifically to be able to engage with narratives and experiences that may not correlate with our narratives and our experiences.

When we start to do a little bit more history, learning and hearing, the instinct for empathy, whatever you might call it, kicks in. At that point, I go to what we call noticing and the naming. If it is the case that you find whenever a conversation around race begins, you either find your body pushing back. You find yourself getting uncomfortable and nervous. I want people to use that as data because that’s valuable. That’s not a bad thing. That’s your body telling you something.

You need to investigate, at that point once you have done some learning, what is going on there. “Am I defensive when certain people talk or share their experiences? Do I shut down? Do I disengage in certain conversations? Why? Is it because maybe I don’t have the answers or this feels out of my element or I don’t have what I need?” Say that. Don’t just walk out of the room or click off the Zoom that you are at least naming and you give me some data that we can work with.

I say the speaker is the last because, at that point, you are ready to say whatever it might be. It might be, “I don’t have the answer. Help me understand more. I’m feeling this way and I don’t like the way I’m feeling. I’m going to be clear and honest.” One of the best conversations I have had was with a White man. He’s a little bit older than me.

He and I had a conversation and he said to me one day, “Dax, I want to be honest with you. I’m struggling with all this DEI stuff. I feel like in many ways, it is everywhere I look. As a White man, I feel like all the work that I have done, the excellence that I have achieved, and all that is being thrown out in many ways. All my career accomplishments, all of a sudden, don’t matter anymore because I’m not “as woke as I need to be” and I resent that.”

I said, “Thank you for saying that because you are a human being. That’s a feeling you have and that’s a legitimate feeling and experience that you are having. I want you to work with that because what you are experiencing is akin to what people have been experiencing for hundreds of years. Their narratives don’t get heard and they feel excluded. They feel like no one cares about what they have accomplished. That is what we are talking about. You can use that resentment and that feeling that you have not to push back a fight but to make some better connections with people who might have been having that same experience for generations. Now they understand they want to be included, too. They want to be heard, too. They want to be able to have X, Y and Z as well. We don’t have a difference in terms of aspiration here.”

I can only happen because he decided that he was going to trust me and we were going to trust each other because I was sharing with him. We want to trust each other enough to be vulnerable and allow that vulnerability to let us express what we feel and what we are wrestling with. Not what Dax wants to hear because it’s not serving me to have you tell me what you think I want to hear. Go out and do whatever.

You rather tell me, “Dax, I disagree and here’s why,” so we could talk about it, then nod and say, “The culture says I have to say I agree so I’m going to say I agree even though my heart doesn’t and I have reservations about this.” It’s hard. You might get some things wrong. I get things wrong. You might lose some friends but you might gain a lot of friends, too. We focus a lot on these conversations, “What am I going to lose?” Whether it’s credibility, authority or whatever versus what we can gain. You never know who might hear you struggle with something. You struggle to articulate and be like, “I see you and I’ve got your back because I see you struggling with me,” versus trying to hold on to this posture of certainty when none of us have that, even if they might not agree with everything.

We would say that all the time in the military. Your bond and unity are a common mission and vision. This is one of those topics. If we are aligned to reach the same end goal and we sit here, and we may have different views at times of how we are going to get there but we know that we are committed to getting to the same place, we stand up and help each other. In the military, we say, “I lay my life on the line for a guy that I didn’t even like but I knew that when he was in the fight, he would do the same thing for me because we had the same goal.”

Dax, this is our conversation. I appreciate your openness, honesty and willingness to sit here with me. This is a critical conversation. Everything we have discussed here helps us to become better individuals, teams and organizations drive societal change in terms of the race conversation. A lot of what you talked about applies to leadership and how do we challenge ourselves as leaders to have difficult conversations and sit here, and in a sense, get in the room, talk about it and do it.

As we wrap this up, I want to have a little bit of fun. I have had a lot of fun here, don’t get me wrong. I want to tie some of the points you made in the book directly to what I want to call Dax’s Decision Points. They are these stepping stones in a leader’s thought process to solve a complex, maybe emotionally charged problem. What I’m going to do is I’m going to throw them out. You come back to me and you tell us what those 2 to 3 top lines mean. The first one is, get a grip.

People short circuit easily and lose sight of the fact that this isn’t always about you personally. This is about we. It’s about a larger set of challenges we face as a society. Don’t personalize everything. Don’t think it’s all about you, so get a grip.

Buckle up.

We are going to be on this ride for a while. Don’t try to get off the ride so quickly. That’s a struggle we have as a society. It has been with us for over 400 years as a problem. Why do you think you could solve it in six months?

Look back on your life.

Our lives are data. If you look back, there have probably been moments, either you passed over certain information and didn’t engage with certain conversations, maybe you didn’t do some of the learning that could be useful or there might be different experiences in your background. We are, in many ways, a set of experiences that we have had, good, bad or indifferent. Look back and use that as an opportunity to figure out how you became who you became.

Resist the urge to turn away.

It’s connected to the buckle-up. I see it a lot in leaders this desire to open up the conversation or to change it to this. Stay here and stay with it. It might feel like it’s not moving but you’ve got to stick with the thing that we are talking about right here because we have been talking about it for a long time and we have made some progress, too. Turning away feels like the easy thing to always do.

It ties into the next one, resisting distraction.