—

—

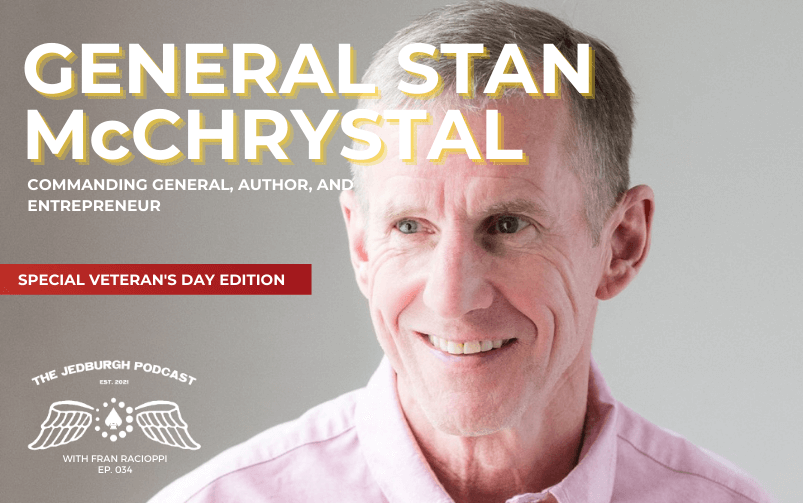

Stanley McChrystal retired in July 2010 as a four-star general in the U.S. Army. He was Commander International Security Assistance Forces – Afghanistan. He had previously served as Director, Joint Staff and Commander Joint Special Operations Command. The author of My Share of the Task, Team of Teams, and Leaders, he is currently a senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and the cofounder of McChrystal Group, a leadership consulting firm.

Stanley McChrystal retired in July 2010 as a four-star general in the U.S. Army. He was Commander International Security Assistance Forces – Afghanistan. He had previously served as Director, Joint Staff and Commander Joint Special Operations Command. The author of My Share of the Task, Team of Teams, and Leaders, he is currently a senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs and the cofounder of McChrystal Group, a leadership consulting firm.

—

Even as a lieutenant, I was doling out as much as I could. If you’re a high-speed specialist, you’re now a corporal. I had corporals, starting on that deployment. By the time I got to company command, I did it to my lieutenants and my captains, if they ever read this they would start giggling because the only thing I tell them I rate them on with regards to their evaluation reports is their ability to deliver through others. I tell them, “You get ranked 1 through 8 on your ability to deliver through others.” For me, I’ve been too overwhelmed to do anything less. It does feel good for about 30 seconds and it’s too much. In battalion command, pretty regularly I say, “It’s too much. You take care of this.”

I do want to set the record straight. I also have a four-year degree in Engineering but if you ever come to a bridge and my name is on it, do not cross it. Your life is in danger.

Lisa teaches in the Risk Academy at the McChrystal Group. You’ve developed what you’re calling The Risk Immune System and there are four critical functions of the risk immune system. Detect, assess, respond and learn. Can you talk about these four functions, the importance of them and how they make up this risk immune system?

Absolutely and I’m going to back up because we drew this from an analogy to the human immune system. Some years ago when I was up at Yale teaching, a young immunologist came and told me that the human immune system is like counterinsurgency. I said, “What do you know about counterinsurgency?” She says, “Nothing but I’ve done a little reading.”

I googled it.

She did and more than I knew about the human immune system but as we studied and we did a project on it together, it was exactly right. A human immune system detects those things which come at us every day and it’s estimated 10,000 microorganisms come into our body a day that could kill us or make us sick. It then assesses every one of them to determine if it’s dangerous to us. It responds by killing it or not and it learns so it’s better next time and yet, we have this miracle system. We don’t worry too much about it unless we’re immune-compromised. We get up in the morning and go about our lives.

When we look at why organizations or individuals struggle with risk, it’s because we’re not good at detecting, assessing, responding and learning to the threats that come at us. If you only think of the things that get to you, not the things that are over the horizon and might come but the things that arrive. If we put ourselves in a position where we’re able to do those four steps, assess those things, detect them, assess them then respond effectively and learn from them, we get better every time. Suddenly, we put in place resilience that we won’t have otherwise. When we talk about the greatest risk to us is us, it’s when we neglect that risk immune system.

What about the ten factors of control, which is now how do you break this down once you’ve gone through the four functions. You’ve called them a set of dials that we can adjust or calibrate to improve the operation of the risk immune system. I’ll list them and we can get into a couple of them. Narrative structure technology, diversity, bias, action, timing, adaptability, leadership and communication. First of all, why these ten? Can you talk a bit about the interrelated nature?

Absolutely. As we tried to decide what are the things that an organization and we thought mostly about organizations have to be able to do effectively, we came up with ten. We could have had 12 or 8 by putting something together but we wanted to make it clear for people. For example, we talked about communication. Any organization that doesn’t communicate internally is dead in the water. If we want to defeat an enemy army, the first thing we do is cut their communications then they can’t collaborate, coordinate and they’re done but some are more subtle like a narrative.

Narratives are what we say about ourselves and what we think about ourselves. In the book, we talk about when a narrative isn’t effective for an organization. In 1957, then-Vice President Nixon went to Ghana for Independence Day. He is walking around making conversation with people and he goes to a black man and he says, “How does it feel to be free?” The man looks and says, “I wouldn’t know. I’m from Alabama.”

It was an extraordinary moment because if you think about America’s narrative has been about freedom, equality, liberty and all the things that we believe in and yet that reality wasn’t true for many Americans. It still isn’t completely true. What we uncover is when we have a gap between what we say our narrative is and what it is in practice then we have a real problem because the say-do gap can create cynicism and problems.

It’s the importance of knowing who we are, what we’re about and why we do it. Each of these ten factors forms into a system. It’s like the principles of war. You don’t have to max all of them perfectly in your plan but any you violate, if you don’t have security, if you don’t see something, you better know it and you better have a good reason why you don’t because you’ve got a gaping hole of vulnerability.

It’s like the nine characteristics of elite performance. You demonstrate all nine but you don’t demonstrate them in equal value all the time. You’re playing on different ones depending on the situation that you’re in and even when you’re being assessed as a SEAL, a Green Beret, a Ranger then you’re looking at some more critically than others based on the job that’s being asked of you. There’s always this give and take with some of them. I want to ask about diversity. That’s an important one and Lisa’s laughing at me but it’s an important subject.

We did an episode with an author, Dax Devlon Ross. He wrote a book on systemic racism and it was called Letters to My White Male Friends that generated the first hate mail I got on the podcast so I figured I was doing something right. Now, we’re having difficult conversations. Lisa was the third female to graduate from Ranger School. We were in the first class. We joke about her path and my path through the course.

He only took nine weeks. He is not a real Ranger.

[bctt tweet=”We need to navigate from where we are, not from where we wish we were.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I didn’t get the full value of the training by getting to do it twice.

You probably went in the summer too.

I went in the winter so I got a little bit of it.

He is from the northeast so that’s a different story.

Lisa has the term, “Delete the adjective.” That’s a big part of her work and the theory that we’ve got to remove the she. We’ve got to remove that adjective that sits before CEO, athlete or leader. You spoke a lot about diversity in the book. You speak about and a lot of the work that you’re doing because there’s a myopic view on diversity where people think, “I have to get people in the room who are of different gender, color, race or creed and I’ve created a diverse audience.”

What I say in this is, “That’s great.” If we all went to Harvard and graduated with the same degree, are we truly thinking with a diverse mindset? I wanted to get both of your thoughts on this from your different perspectives because how we achieve diversity has to be quantified in who is sitting in the room and their background. Also, their contribution from their experiences and what we call effective intelligence, 1 of those 9 soft characteristics.

I’ll start by saying that the way about it may be a bit different than some people so it’s important I framed my comments. First, equality of opportunity is a right. It’s a legal right and it is a moral right. We should seek to give everyone equality of opportunity. That’s hard. We’re not close to that yet but we should do that because it is morally right and legally right. That is not how I talk about diversity. When I think of diversity, it is different perspectives, expertise and experience in the room. You don’t do diversity because it’s a legal right or a moral right. You do it because it’s smart. It’s what works.

In the book, we describe the Bay of Pigs. What happens is in 1961, the brand new president, President Kennedy gets a group of people, a bunch of essentially old white guys, they weren’t really old but they were World War II veteran white guys because that was the government then. What he does is he gets people with a pretty limited set of perspectives. He asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff for their opinion but they don’t want to give it. They’re haphazard so he doesn’t even get that perspective. The thing goes badly wrong and it should have been evident from the beginning.

What he didn’t achieve was getting a diversity of perspectives into the decision-making process. Eighteen months later with the Cuban Missile Crisis, he does much better. It’s still a bunch of white guys because it’s the US government in 1962 but the reality is he intentionally brings different perspectives into the room so he can create the dynamic. What he was trying to do is give himself a broader range of options.

I go to my own experience in Special Operations in the counter-terrorist world. When I was younger, we all looked like me, except everybody had bigger arms, biceps and whatnot than me. We were selected for that. Some of it was intentional and some of it was unintentional. We got into the fight after 9/11, the fight against Al Qaeda in Iraq and that was the first time we were in danger of losing. Before that you did operations it was you’re going to do it well or really well. Suddenly, we are in the specter of losing a war. I was right in the middle of it. We once had a meeting where we got key leaders together and asked if we’d already lost and we’re too stupid to admit it. What happened in the organization is we started becoming diverse not because I put out a policy directive but because we had to be a meritocracy.

It started mostly in intel and in communications but then it seeped across the organization because you needed the best people doing things at the best time. People didn’t want to hear your war stories from a previous war because that was important. What was important was who could get the job done. We had to boot a group of great, largely females but also there were other minorities some older men and people of different demographics that became most valuable players.

The organization’s social hierarchy started to be modified. It started to be modified in ways that we didn’t direct but had an important impact on us, which increased opportunities and whatnot. In my opinion, now, what you’ve got to do is you’ve got to understand that if you’re looking at an elephant, you’ve got five blind men. You better get them all together so they’re ones looking at the trunk, tail and you can put that together. You’ve got to be thoughtful enough to put that together and it’s not comfortable to do. It’s not getting your buds around who were all at your wedding. It’s getting the people who you didn’t know before.

It takes courage and you have to have the courage to have difficult conversations and be challenged. There’s an element of humility in there. Sometimes people don’t want to hear it, especially if they’re in charge and they’ve been in charge a long time. They’re somewhat stuck in their ways. Lisa, I want to get your thoughts.

Even as a lieutenant, I was doling out as much as I could. If you’re a high-speed specialist, you’re now a corporal. I had corporals, starting on that deployment. By the time I got to company command, I did it to my lieutenants and my captains, if they ever read this they would start giggling because the only thing I tell them I rate them on with regards to their evaluation reports is their ability to deliver through others. I tell them, “You get ranked 1 through 8 on your ability to deliver through others.” For me, I’ve been too overwhelmed to do anything less. It does feel good for about 30 seconds and it’s too much. In battalion command, pretty regularly I say, “It’s too much. You take care of this.”

I do want to set the record straight. I also have a four-year degree in Engineering but if you ever come to a bridge and my name is on it, do not cross it. Your life is in danger.

Lisa teaches in the Risk Academy at the McChrystal Group. You’ve developed what you’re calling The Risk Immune System and there are four critical functions of the risk immune system. Detect, assess, respond and learn. Can you talk about these four functions, the importance of them and how they make up this risk immune system?

Absolutely and I’m going to back up because we drew this from an analogy to the human immune system. Some years ago when I was up at Yale teaching, a young immunologist came and told me that the human immune system is like counterinsurgency. I said, “What do you know about counterinsurgency?” She says, “Nothing but I’ve done a little reading.”

I googled it.

She did and more than I knew about the human immune system but as we studied and we did a project on it together, it was exactly right. A human immune system detects those things which come at us every day and it’s estimated 10,000 microorganisms come into our body a day that could kill us or make us sick. It then assesses every one of them to determine if it’s dangerous to us. It responds by killing it or not and it learns so it’s better next time and yet, we have this miracle system. We don’t worry too much about it unless we’re immune-compromised. We get up in the morning and go about our lives.

When we look at why organizations or individuals struggle with risk, it’s because we’re not good at detecting, assessing, responding and learning to the threats that come at us. If you only think of the things that get to you, not the things that are over the horizon and might come but the things that arrive. If we put ourselves in a position where we’re able to do those four steps, assess those things, detect them, assess them then respond effectively and learn from them, we get better every time. Suddenly, we put in place resilience that we won’t have otherwise. When we talk about the greatest risk to us is us, it’s when we neglect that risk immune system.

What about the ten factors of control, which is now how do you break this down once you’ve gone through the four functions. You’ve called them a set of dials that we can adjust or calibrate to improve the operation of the risk immune system. I’ll list them and we can get into a couple of them. Narrative structure technology, diversity, bias, action, timing, adaptability, leadership and communication. First of all, why these ten? Can you talk a bit about the interrelated nature?

Absolutely. As we tried to decide what are the things that an organization and we thought mostly about organizations have to be able to do effectively, we came up with ten. We could have had 12 or 8 by putting something together but we wanted to make it clear for people. For example, we talked about communication. Any organization that doesn’t communicate internally is dead in the water. If we want to defeat an enemy army, the first thing we do is cut their communications then they can’t collaborate, coordinate and they’re done but some are more subtle like a narrative.

Narratives are what we say about ourselves and what we think about ourselves. In the book, we talk about when a narrative isn’t effective for an organization. In 1957, then-Vice President Nixon went to Ghana for Independence Day. He is walking around making conversation with people and he goes to a black man and he says, “How does it feel to be free?” The man looks and says, “I wouldn’t know. I’m from Alabama.”

It was an extraordinary moment because if you think about America’s narrative has been about freedom, equality, liberty and all the things that we believe in and yet that reality wasn’t true for many Americans. It still isn’t completely true. What we uncover is when we have a gap between what we say our narrative is and what it is in practice then we have a real problem because the say-do gap can create cynicism and problems.

It’s the importance of knowing who we are, what we’re about and why we do it. Each of these ten factors forms into a system. It’s like the principles of war. You don’t have to max all of them perfectly in your plan but any you violate, if you don’t have security, if you don’t see something, you better know it and you better have a good reason why you don’t because you’ve got a gaping hole of vulnerability.

It’s like the nine characteristics of elite performance. You demonstrate all nine but you don’t demonstrate them in equal value all the time. You’re playing on different ones depending on the situation that you’re in and even when you’re being assessed as a SEAL, a Green Beret, a Ranger then you’re looking at some more critically than others based on the job that’s being asked of you. There’s always this give and take with some of them. I want to ask about diversity. That’s an important one and Lisa’s laughing at me but it’s an important subject.

We did an episode with an author, Dax Devlon Ross. He wrote a book on systemic racism and it was called Letters to My White Male Friends that generated the first hate mail I got on the podcast so I figured I was doing something right. Now, we’re having difficult conversations. Lisa was the third female to graduate from Ranger School. We were in the first class. We joke about her path and my path through the course.

He only took nine weeks. He is not a real Ranger.

[bctt tweet=”We need to navigate from where we are, not from where we wish we were.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I didn’t get the full value of the training by getting to do it twice.

You probably went in the summer too.

I went in the winter so I got a little bit of it.

He is from the northeast so that’s a different story.

Lisa has the term, “Delete the adjective.” That’s a big part of her work and the theory that we’ve got to remove the she. We’ve got to remove that adjective that sits before CEO, athlete or leader. You spoke a lot about diversity in the book. You speak about and a lot of the work that you’re doing because there’s a myopic view on diversity where people think, “I have to get people in the room who are of different gender, color, race or creed and I’ve created a diverse audience.”

What I say in this is, “That’s great.” If we all went to Harvard and graduated with the same degree, are we truly thinking with a diverse mindset? I wanted to get both of your thoughts on this from your different perspectives because how we achieve diversity has to be quantified in who is sitting in the room and their background. Also, their contribution from their experiences and what we call effective intelligence, 1 of those 9 soft characteristics.

I’ll start by saying that the way about it may be a bit different than some people so it’s important I framed my comments. First, equality of opportunity is a right. It’s a legal right and it is a moral right. We should seek to give everyone equality of opportunity. That’s hard. We’re not close to that yet but we should do that because it is morally right and legally right. That is not how I talk about diversity. When I think of diversity, it is different perspectives, expertise and experience in the room. You don’t do diversity because it’s a legal right or a moral right. You do it because it’s smart. It’s what works.

In the book, we describe the Bay of Pigs. What happens is in 1961, the brand new president, President Kennedy gets a group of people, a bunch of essentially old white guys, they weren’t really old but they were World War II veteran white guys because that was the government then. What he does is he gets people with a pretty limited set of perspectives. He asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff for their opinion but they don’t want to give it. They’re haphazard so he doesn’t even get that perspective. The thing goes badly wrong and it should have been evident from the beginning.

What he didn’t achieve was getting a diversity of perspectives into the decision-making process. Eighteen months later with the Cuban Missile Crisis, he does much better. It’s still a bunch of white guys because it’s the US government in 1962 but the reality is he intentionally brings different perspectives into the room so he can create the dynamic. What he was trying to do is give himself a broader range of options.

I go to my own experience in Special Operations in the counter-terrorist world. When I was younger, we all looked like me, except everybody had bigger arms, biceps and whatnot than me. We were selected for that. Some of it was intentional and some of it was unintentional. We got into the fight after 9/11, the fight against Al Qaeda in Iraq and that was the first time we were in danger of losing. Before that you did operations it was you’re going to do it well or really well. Suddenly, we are in the specter of losing a war. I was right in the middle of it. We once had a meeting where we got key leaders together and asked if we’d already lost and we’re too stupid to admit it. What happened in the organization is we started becoming diverse not because I put out a policy directive but because we had to be a meritocracy.

It started mostly in intel and in communications but then it seeped across the organization because you needed the best people doing things at the best time. People didn’t want to hear your war stories from a previous war because that was important. What was important was who could get the job done. We had to boot a group of great, largely females but also there were other minorities some older men and people of different demographics that became most valuable players.

The organization’s social hierarchy started to be modified. It started to be modified in ways that we didn’t direct but had an important impact on us, which increased opportunities and whatnot. In my opinion, now, what you’ve got to do is you’ve got to understand that if you’re looking at an elephant, you’ve got five blind men. You better get them all together so they’re ones looking at the trunk, tail and you can put that together. You’ve got to be thoughtful enough to put that together and it’s not comfortable to do. It’s not getting your buds around who were all at your wedding. It’s getting the people who you didn’t know before.

It takes courage and you have to have the courage to have difficult conversations and be challenged. There’s an element of humility in there. Sometimes people don’t want to hear it, especially if they’re in charge and they’ve been in charge a long time. They’re somewhat stuck in their ways. Lisa, I want to get your thoughts.

I love the, “Everybody went to Harvard” example. In cognitive diversity, I read an article so my drug of choice is when I fly by the Harvard Business Review, a Coke Zero and a chocolate bar. That’s my treat for traveling. I was reading it and I ended up screenshotting and taking pictures of the Harvard Business Review where it talked about cognitive diversity. I’ve always been the token. I’m in a group in the military that works construction and in the energy industry. It’s predominantly male. It’s the same demographic and people are like, “We have Lisa in here. We have diversity.” Am I a diversity? I have long hair. That’s the only thing that’s different from the guy sitting next to me.

Cognitive diversity is where you start getting innovation and innovation. It’s easy to talk about innovation in the military. We don’t talk about it as much but it goes across the board. It’s different ways of thinking but I do believe that when we force diversity, we end up losing a lot because the people in the room either are the same cognitively or they’re so different that they can’t come together and understand Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Is everybody safe and comfortable? We’re all going for that. I’m going for it differently than you are but if I can’t have open and honest conversations because I don’t have some tie with the other people on the team, we lose the benefit of diversity.

This is something that I have been struggling with regards to the diversity topic and with regards to getting a cornucopia-looking staff section. What is the benefit of recruiting somebody from a different demographic? If you’re not recruiting for that cognitive diversity, are you bringing somebody in who has a solid route in a different culture that might think like you but be able to advertise? In the military, I’m thinking about the CSTs, the Combat Support Teams. They looked different but they were as motivated as the rest of the soldiers so there are times where the visual diversity is also critical. I’m all over the map with regard to diversity.

Let me ask you an opinion because I want to throw up to both of you a pet idea that I have come up with in the last few years. The military largely is a guild. You have to enter it at a young age and a young rank and work your way up. You can’t be a captain unless you are a lieutenant and vice versa. As a danger, even if you start with diversity at the bottom, you’re all pretty similar by the time your colonels. You should have had similar experiences and whatnot. I’m a believer that we should have lateral entry to the military.

A major, lieutenant colonel, colonel and even general officer could bring in people from the business. I’m not talking about an expert and treat them like an albino unicorn who sits in the corner. I’m talking about bringing people in, putting them in charge of brigades and divisions. I’ve run into business executives who could walk in tomorrow and they pump fresh air into what we do and they’ve got enough smart people around them to not make any big mistakes militarily. What do you all think?

[bctt tweet=”Truth only comes out of getting all those perspectives and knitting them together because you may have your view and it may be right in your truth because that’s what you saw, but it can be so incomplete or so flawed that you draw completely wrong conclusions.” username=”talentwargroup”]

In some specialties, I know that does occur. In the engineering field, I have wanted to push for it more to have more technical engineering because military engineer training is wood and nails and sometimes some concrete. There’s a lot that’s out there that we could pull in from Corporate America that would be beneficial to our military but the system already exists and we don’t use it right. That’s people like me. I am a much better officer as a reserve battalion commander than I would have been had I gone single track.

During my last deployment to Iraq, I was utilized all over the country and got sent to Muscat, Oman to advise at their engineering schoolhouse. It’s not because of anything that the army taught me but because of my work at Shell Oil Company and other businesses. Also, knowing Corporate America and knowing how to communicate with non-military personnel. We’ve got our contracting processes. Those don’t fly outside of DOD supported. We have operationalized our reserve and National Guard and we should be leveraging and pushing the reserve National Guard to do more with their civilian careers and pull them in as needed and that’s my humble opinion.

You asked that question and you said that and that’s something that I’ve never thought about. If you look at organizations in the civilian world who do this and I’m thinking about the McKinseys of the world, PwC, Bain, the big consulting firms, there are two tracks in there. You can come in as a junior analyst and work your way up or you can come in as an experienced hire. Those systems work because they bring incredible value even coming in at a more senior level.

Lisa, what you’re talking about in your two worlds of being a reservist and you go to your not your civilian job but your civilian job is increasing your skills in parallel probably at an accelerated rate and in certainly a more diverse application. Meaning you’re working on more projects that look much different from your civilian job than you would be if you were only gaining engineering experience through your military and the military projects that you’re working on.

You’re accelerating and growing a skill set at a much higher rate. I’m also thinking about the political environment. We put political appointees as ambassadors who come out of businesses. Some don’t do well but many do well or they go in as policy advisors and they do well out of their civilian experience. You might be onto something.

It’s interesting because when I retired, there were a bunch of my peers who wondered why we don’t get invited to be the CEOs of companies and things like that. You flip that and say, “Why don’t we invite some of them to come in and be senior leaders in the military, not just appointees?” Do we think our business is so much harder than every other business that nobody could learn it on the fly? You go to times like World War II when we had to bring people in. Arguably, it worked pretty well in a lot of cases.

You meet CEOs and executive leaders in companies all the time and you say, “That’s one of the greatest leaders I’ve ever seen,” and they never served a day in the military. They’re amazing at what they do. I want to transition a little bit to Afghanistan. There are so many types of risks and we’ll quantify the Afghanistan conversation in types of risks.

To name a few, there are economic compliances, security, market credit, operational, strategic reputational risk, business risk and the list can go on and on. All of these types of risks would then have these sub-lists of different risks and also the threats and the vulnerabilities that you spoke about that will make up each one of them.

I feel like we, as leaders, rarely ever get to choose the situation that we inherit. Especially when you talked about progressing in the military and how many times you get thrown into a job and it’s like, “Here’s the shit sandwich that you get. Get ready. You’ve got to figure this thing out.” We have to figure out ways to mitigate. We’re putting these situations that you were put in and you led all forces in Afghanistan as the commander of the International Security Assistance Force. You led JSOC at a critical time, a growing organization that set an identity of that organization that permeates through now.

You witnessed firsthand the effects of risk on our nation and the world but you saw it not only on the effect on the countries that you operate in but on our most precious asset, our people, the military people and the civilian population. I told you that we’ve talked to Chris Miller in No One Left Behind in our 9/11 episode. We got into Afghanistan, the effect that Afghanistan has had on people like Chris and yourself who were there in the early days. I was a college student. I watched it on TV and was motivated to go do great things after that.

You saw this whole evolution and lived it and you saw this withdrawal. You said that you would have advised leaving a small force there on the ground. When you were in command, your perspective was, “In order to win this thing and win this thing decisively. We needed 30,000 or 40,000 troops to go all the way in.” You also said that the President’s decision was a courageous decision. I’m wondering if you could talk about your perspectives on Afghanistan, coming out of Afghanistan and the driving factors behind it. Also, when you sit at that level that you have and you’ve been a part of these decisions, you have these ten factors of control that you talked about. What is that checklist like?

It’s challenging and I’ll start with that last point first. A country or an organization making tough decisions has to have an effective risk immune system because otherwise, it can’t go through the process to reach a rational decision that’s effective. If I go back to our challenge in Afghanistan and you can go back as far as you want but we’ll go back to the mid-1970s when Afghanistan started to struggle internally. They flirted first with socialism and they had a Soviet intervention in 1979. They went through about twenty years first of a fight against the Soviets, which was essentially a civil war. They had a civil war among the Mus groups and they had to fight against the Taliban.

Until 2001, it was torn apart for almost two decades. 9/11 occurred in 2001 and the United States and other Western nations went to Afghanistan not because we were invited or they asked us to but because it was in our interest to go after Al Qaeda, who had planned the 9/11 attacks from there. We went in to do whatever we could to stop those sanctuaries from being a threat to the United States. In so doing, we overthrew the government, which was a Taliban-controlled government.

It wasn’t our stated aim before but that was an implied task and doing it. Once we did that, we were in a funny position. We had forced Al Qaeda at least to the hills. We hadn’t destroyed them completely but we eliminated the obvious sanctuaries. We’re there and Afghanistan has been torn for more than twenty years and now it’s got no government. What do you do? Can you walk away? People made the decision for a couple of reasons. One because we didn’t want an Al Qaeda sanctuary to be established again. Also because when things are torn apart in the economy and whatnot, you feel a moral and a practical obligation to set things in the right direction.

That was a difficult point because, in the fall of 2001, we started a train of events without clarifying for the nation where we were trying to go and what our national objectives were. We would talk about it occasionally. Our number one objective was to prevent Al Qaeda’s resurgence. The second objective is to avoid having an atmosphere inside Afghanistan that could allow a sanctuary. From that, you derive the idea that therefore, we’ve got to create sovereignty. Afghanistan’s got to be able to control its borders and land to do that. If they’re going to create sovereignty, they’ve got to have a functional government and a security arm.

It’s not hard to get to the point where we’ve got to help the state of Afghanistan to stand up and exist in a viable way if we are going to achieve our first and stated missions at preventing the sanctuary. We argued over that on and off for the first few years but we didn’t do much in Afghanistan. The American people didn’t realize it but the level of effort was pretty low on the part of all the West. I was there initially when we stood up the Afghan army and it was laughable.

They sent a member of the administration around to Europe to ask for cash donations, almost like with a bag to get money. At one point, they came back with 600 Romanian AK 47s and this was, “We’re going to equip the Afghan army.” You don’t build an army by getting someone to donate 600 Romanian AK 47s and get a bag of money. You’ve got to build up logistics and personnel. You’ve got to create something. For the first 7 or 8 years, the level of effort on that, the police and the courts were minuscule. Part of that was the distraction of Iraq but part of that was the level of effort and lack of clarity on what the end state we wanted was.

You get to 2008 and 2009. Iraq starts to be more settled and Afghanistan starts to get worse because the Taliban have gotten traction to come back. We still had a difficult time fighting and deciding what our national priorities were. What level of effort were we willing to put against those? We signaled to ourselves and to the Afghan people and to our enemies that we had a limited level of commitment. We would love to have Afghanistan stand up as a sovereign nation. That would be great but we’re not willing to commit too much to do that.

[bctt tweet=”The number one threat to us now is our own dysfunction.” username=”talentwargroup”]

It’s like playing poker with somebody and you don’t know what cards they have. You have an idea but they are willing to see every bet and raise each time. The Taliban are not going anywhere. It’s like what the North Vietnamese did. They basically signaled to us, “There is no level of effort that will make us quit. Unless you kill us all, there’s no level of effort to make us quit.” There is a level of effort at which you will quit.

We even signaled to ourselves that we will never put in more than a certain level of effort. As soon as we can, we’ll pull out so we are conflicted internally and signaling that externally in there. They are not. You run into a mismatch, asymmetric warfare and want to talk about asymmetric commitment. As we go forward to Afghanistan, the Afghan people sense this. They understand that there’s a limit to what America will do so they go through this increasing uncertainty and I call it insecurity, almost like a child of a broken marriage. One parent has left, the parent comes back for a while and they’re always looking to see if that parent is going to leave again.

The Afghan people had a collective psyche that was convinced that we were looking at the exit and as soon as we could, we would leave. We routinely signal that although we didn’t intentionally do that. Then the Doha Accord was signed and we promised all American military would leave by May 1, 2021. You’ve got a situation in which the Afghan people lack confidence in their own government, which had given great reason for a lack of confidence but also they were convinced that we were going to leave as quickly as we could. The Taliban did a good information warfare campaign over years to signal they were the inevitable winners. It’s going to take a while but we will win.

The Afghan people have this sense of insecurity. President Biden enters office so we talk about tough decisions. He’s got two options. He can abrogate the agreement that President Trump made, in which case, you’re going to extend the war. The Taliban are likely to start attacking Americans again and President Biden will now personally own the Forever War, which he doesn’t want to do. The other option is to follow through on the withdrawal, in which case even though his predecessor signed the agreement, President Biden’s going to own it if, in fact, a sanctuary rearises. He’s caught between these two difficult decisions.

As I’ve told people, if they’d asked me what I would have done, I would have left a force there. We could have buttressed Afghan confidence and their government but I’m also honest enough to tell you, I’m biased. I was there and I cared about the Afghan people so I probably shouldn’t have been given that decision to make because I walk in with a bias to it.

Whether it’s a right decision or a wrong one, President Biden’s choice was courageous because he was going to get attacked no matter what he did. The mechanics of the departure were unfortunate. I’m not as critical as some people are because I know how hard it is to withdraw a force out of a country like that and to predict what was going to happen was difficult as well. It was a tough decision. Now the question is what does it mean now? We go back to what were our priorities and interests in the first place.

The first is, if we were worried about Al Qaeda or ISIS sanctuary growing, the chances of that happening are not zero but they’re not huge and they’re not greater than them going somewhere else and creating a sanctuary. You don’t need big base camps and training camps to do that anymore. Much of this can be done with cyber and whatnot. To the US homeland, that part of the danger is not much increased.

In the region, you can say that a Taliban-run Afghanistan or resumption of civil war is going to destabilize the region and that’s not a good thing but it’s probably not an international problem. The last one that is emotional for all of us is the reputational risk. We lost. There’s no way to say we didn’t because we didn’t achieve our goals. Is that going to create a lack of confidence in us in the world? I’m not selling the Domino Theory from the Vietnam era but there’s a cost there. We can’t pretend there isn’t.

We are viewed as less reliable partners, less consistent and less resolute than we would like to be considered so we’ve got to factor all that in. We’ve got to navigate from where we are not from where we wish we were. Now what we’ve got to do is figure out what our interests are going forward and see how we best achieve those.

I love the, “Everybody went to Harvard” example. In cognitive diversity, I read an article so my drug of choice is when I fly by the Harvard Business Review, a Coke Zero and a chocolate bar. That’s my treat for traveling. I was reading it and I ended up screenshotting and taking pictures of the Harvard Business Review where it talked about cognitive diversity. I’ve always been the token. I’m in a group in the military that works construction and in the energy industry. It’s predominantly male. It’s the same demographic and people are like, “We have Lisa in here. We have diversity.” Am I a diversity? I have long hair. That’s the only thing that’s different from the guy sitting next to me.

Cognitive diversity is where you start getting innovation and innovation. It’s easy to talk about innovation in the military. We don’t talk about it as much but it goes across the board. It’s different ways of thinking but I do believe that when we force diversity, we end up losing a lot because the people in the room either are the same cognitively or they’re so different that they can’t come together and understand Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Is everybody safe and comfortable? We’re all going for that. I’m going for it differently than you are but if I can’t have open and honest conversations because I don’t have some tie with the other people on the team, we lose the benefit of diversity.

This is something that I have been struggling with regards to the diversity topic and with regards to getting a cornucopia-looking staff section. What is the benefit of recruiting somebody from a different demographic? If you’re not recruiting for that cognitive diversity, are you bringing somebody in who has a solid route in a different culture that might think like you but be able to advertise? In the military, I’m thinking about the CSTs, the Combat Support Teams. They looked different but they were as motivated as the rest of the soldiers so there are times where the visual diversity is also critical. I’m all over the map with regard to diversity.

Let me ask you an opinion because I want to throw up to both of you a pet idea that I have come up with in the last few years. The military largely is a guild. You have to enter it at a young age and a young rank and work your way up. You can’t be a captain unless you are a lieutenant and vice versa. As a danger, even if you start with diversity at the bottom, you’re all pretty similar by the time your colonels. You should have had similar experiences and whatnot. I’m a believer that we should have lateral entry to the military.

A major, lieutenant colonel, colonel and even general officer could bring in people from the business. I’m not talking about an expert and treat them like an albino unicorn who sits in the corner. I’m talking about bringing people in, putting them in charge of brigades and divisions. I’ve run into business executives who could walk in tomorrow and they pump fresh air into what we do and they’ve got enough smart people around them to not make any big mistakes militarily. What do you all think?

[bctt tweet=”Truth only comes out of getting all those perspectives and knitting them together because you may have your view and it may be right in your truth because that’s what you saw, but it can be so incomplete or so flawed that you draw completely wrong conclusions.” username=”talentwargroup”]

In some specialties, I know that does occur. In the engineering field, I have wanted to push for it more to have more technical engineering because military engineer training is wood and nails and sometimes some concrete. There’s a lot that’s out there that we could pull in from Corporate America that would be beneficial to our military but the system already exists and we don’t use it right. That’s people like me. I am a much better officer as a reserve battalion commander than I would have been had I gone single track.

During my last deployment to Iraq, I was utilized all over the country and got sent to Muscat, Oman to advise at their engineering schoolhouse. It’s not because of anything that the army taught me but because of my work at Shell Oil Company and other businesses. Also, knowing Corporate America and knowing how to communicate with non-military personnel. We’ve got our contracting processes. Those don’t fly outside of DOD supported. We have operationalized our reserve and National Guard and we should be leveraging and pushing the reserve National Guard to do more with their civilian careers and pull them in as needed and that’s my humble opinion.

You asked that question and you said that and that’s something that I’ve never thought about. If you look at organizations in the civilian world who do this and I’m thinking about the McKinseys of the world, PwC, Bain, the big consulting firms, there are two tracks in there. You can come in as a junior analyst and work your way up or you can come in as an experienced hire. Those systems work because they bring incredible value even coming in at a more senior level.

Lisa, what you’re talking about in your two worlds of being a reservist and you go to your not your civilian job but your civilian job is increasing your skills in parallel probably at an accelerated rate and in certainly a more diverse application. Meaning you’re working on more projects that look much different from your civilian job than you would be if you were only gaining engineering experience through your military and the military projects that you’re working on.

You’re accelerating and growing a skill set at a much higher rate. I’m also thinking about the political environment. We put political appointees as ambassadors who come out of businesses. Some don’t do well but many do well or they go in as policy advisors and they do well out of their civilian experience. You might be onto something.

It’s interesting because when I retired, there were a bunch of my peers who wondered why we don’t get invited to be the CEOs of companies and things like that. You flip that and say, “Why don’t we invite some of them to come in and be senior leaders in the military, not just appointees?” Do we think our business is so much harder than every other business that nobody could learn it on the fly? You go to times like World War II when we had to bring people in. Arguably, it worked pretty well in a lot of cases.

You meet CEOs and executive leaders in companies all the time and you say, “That’s one of the greatest leaders I’ve ever seen,” and they never served a day in the military. They’re amazing at what they do. I want to transition a little bit to Afghanistan. There are so many types of risks and we’ll quantify the Afghanistan conversation in types of risks.

To name a few, there are economic compliances, security, market credit, operational, strategic reputational risk, business risk and the list can go on and on. All of these types of risks would then have these sub-lists of different risks and also the threats and the vulnerabilities that you spoke about that will make up each one of them.

I feel like we, as leaders, rarely ever get to choose the situation that we inherit. Especially when you talked about progressing in the military and how many times you get thrown into a job and it’s like, “Here’s the shit sandwich that you get. Get ready. You’ve got to figure this thing out.” We have to figure out ways to mitigate. We’re putting these situations that you were put in and you led all forces in Afghanistan as the commander of the International Security Assistance Force. You led JSOC at a critical time, a growing organization that set an identity of that organization that permeates through now.

You witnessed firsthand the effects of risk on our nation and the world but you saw it not only on the effect on the countries that you operate in but on our most precious asset, our people, the military people and the civilian population. I told you that we’ve talked to Chris Miller in No One Left Behind in our 9/11 episode. We got into Afghanistan, the effect that Afghanistan has had on people like Chris and yourself who were there in the early days. I was a college student. I watched it on TV and was motivated to go do great things after that.

You saw this whole evolution and lived it and you saw this withdrawal. You said that you would have advised leaving a small force there on the ground. When you were in command, your perspective was, “In order to win this thing and win this thing decisively. We needed 30,000 or 40,000 troops to go all the way in.” You also said that the President’s decision was a courageous decision. I’m wondering if you could talk about your perspectives on Afghanistan, coming out of Afghanistan and the driving factors behind it. Also, when you sit at that level that you have and you’ve been a part of these decisions, you have these ten factors of control that you talked about. What is that checklist like?

It’s challenging and I’ll start with that last point first. A country or an organization making tough decisions has to have an effective risk immune system because otherwise, it can’t go through the process to reach a rational decision that’s effective. If I go back to our challenge in Afghanistan and you can go back as far as you want but we’ll go back to the mid-1970s when Afghanistan started to struggle internally. They flirted first with socialism and they had a Soviet intervention in 1979. They went through about twenty years first of a fight against the Soviets, which was essentially a civil war. They had a civil war among the Mus groups and they had to fight against the Taliban.

Until 2001, it was torn apart for almost two decades. 9/11 occurred in 2001 and the United States and other Western nations went to Afghanistan not because we were invited or they asked us to but because it was in our interest to go after Al Qaeda, who had planned the 9/11 attacks from there. We went in to do whatever we could to stop those sanctuaries from being a threat to the United States. In so doing, we overthrew the government, which was a Taliban-controlled government.

It wasn’t our stated aim before but that was an implied task and doing it. Once we did that, we were in a funny position. We had forced Al Qaeda at least to the hills. We hadn’t destroyed them completely but we eliminated the obvious sanctuaries. We’re there and Afghanistan has been torn for more than twenty years and now it’s got no government. What do you do? Can you walk away? People made the decision for a couple of reasons. One because we didn’t want an Al Qaeda sanctuary to be established again. Also because when things are torn apart in the economy and whatnot, you feel a moral and a practical obligation to set things in the right direction.

That was a difficult point because, in the fall of 2001, we started a train of events without clarifying for the nation where we were trying to go and what our national objectives were. We would talk about it occasionally. Our number one objective was to prevent Al Qaeda’s resurgence. The second objective is to avoid having an atmosphere inside Afghanistan that could allow a sanctuary. From that, you derive the idea that therefore, we’ve got to create sovereignty. Afghanistan’s got to be able to control its borders and land to do that. If they’re going to create sovereignty, they’ve got to have a functional government and a security arm.

It’s not hard to get to the point where we’ve got to help the state of Afghanistan to stand up and exist in a viable way if we are going to achieve our first and stated missions at preventing the sanctuary. We argued over that on and off for the first few years but we didn’t do much in Afghanistan. The American people didn’t realize it but the level of effort was pretty low on the part of all the West. I was there initially when we stood up the Afghan army and it was laughable.

They sent a member of the administration around to Europe to ask for cash donations, almost like with a bag to get money. At one point, they came back with 600 Romanian AK 47s and this was, “We’re going to equip the Afghan army.” You don’t build an army by getting someone to donate 600 Romanian AK 47s and get a bag of money. You’ve got to build up logistics and personnel. You’ve got to create something. For the first 7 or 8 years, the level of effort on that, the police and the courts were minuscule. Part of that was the distraction of Iraq but part of that was the level of effort and lack of clarity on what the end state we wanted was.

You get to 2008 and 2009. Iraq starts to be more settled and Afghanistan starts to get worse because the Taliban have gotten traction to come back. We still had a difficult time fighting and deciding what our national priorities were. What level of effort were we willing to put against those? We signaled to ourselves and to the Afghan people and to our enemies that we had a limited level of commitment. We would love to have Afghanistan stand up as a sovereign nation. That would be great but we’re not willing to commit too much to do that.

[bctt tweet=”The number one threat to us now is our own dysfunction.” username=”talentwargroup”]

It’s like playing poker with somebody and you don’t know what cards they have. You have an idea but they are willing to see every bet and raise each time. The Taliban are not going anywhere. It’s like what the North Vietnamese did. They basically signaled to us, “There is no level of effort that will make us quit. Unless you kill us all, there’s no level of effort to make us quit.” There is a level of effort at which you will quit.

We even signaled to ourselves that we will never put in more than a certain level of effort. As soon as we can, we’ll pull out so we are conflicted internally and signaling that externally in there. They are not. You run into a mismatch, asymmetric warfare and want to talk about asymmetric commitment. As we go forward to Afghanistan, the Afghan people sense this. They understand that there’s a limit to what America will do so they go through this increasing uncertainty and I call it insecurity, almost like a child of a broken marriage. One parent has left, the parent comes back for a while and they’re always looking to see if that parent is going to leave again.

The Afghan people had a collective psyche that was convinced that we were looking at the exit and as soon as we could, we would leave. We routinely signal that although we didn’t intentionally do that. Then the Doha Accord was signed and we promised all American military would leave by May 1, 2021. You’ve got a situation in which the Afghan people lack confidence in their own government, which had given great reason for a lack of confidence but also they were convinced that we were going to leave as quickly as we could. The Taliban did a good information warfare campaign over years to signal they were the inevitable winners. It’s going to take a while but we will win.

The Afghan people have this sense of insecurity. President Biden enters office so we talk about tough decisions. He’s got two options. He can abrogate the agreement that President Trump made, in which case, you’re going to extend the war. The Taliban are likely to start attacking Americans again and President Biden will now personally own the Forever War, which he doesn’t want to do. The other option is to follow through on the withdrawal, in which case even though his predecessor signed the agreement, President Biden’s going to own it if, in fact, a sanctuary rearises. He’s caught between these two difficult decisions.

As I’ve told people, if they’d asked me what I would have done, I would have left a force there. We could have buttressed Afghan confidence and their government but I’m also honest enough to tell you, I’m biased. I was there and I cared about the Afghan people so I probably shouldn’t have been given that decision to make because I walk in with a bias to it.

Whether it’s a right decision or a wrong one, President Biden’s choice was courageous because he was going to get attacked no matter what he did. The mechanics of the departure were unfortunate. I’m not as critical as some people are because I know how hard it is to withdraw a force out of a country like that and to predict what was going to happen was difficult as well. It was a tough decision. Now the question is what does it mean now? We go back to what were our priorities and interests in the first place.

The first is, if we were worried about Al Qaeda or ISIS sanctuary growing, the chances of that happening are not zero but they’re not huge and they’re not greater than them going somewhere else and creating a sanctuary. You don’t need big base camps and training camps to do that anymore. Much of this can be done with cyber and whatnot. To the US homeland, that part of the danger is not much increased.

In the region, you can say that a Taliban-run Afghanistan or resumption of civil war is going to destabilize the region and that’s not a good thing but it’s probably not an international problem. The last one that is emotional for all of us is the reputational risk. We lost. There’s no way to say we didn’t because we didn’t achieve our goals. Is that going to create a lack of confidence in us in the world? I’m not selling the Domino Theory from the Vietnam era but there’s a cost there. We can’t pretend there isn’t.

We are viewed as less reliable partners, less consistent and less resolute than we would like to be considered so we’ve got to factor all that in. We’ve got to navigate from where we are not from where we wish we were. Now what we’ve got to do is figure out what our interests are going forward and see how we best achieve those.

Gen. Stanley McChrystal was the commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan until 2010. His new memoir chronicles his military career.

You are a graduate of West Point, the Naval War College, you’ve done fellowships at Harvard in the John F. Kennedy School of Government in the Council of Foreign Relations. You teach at Yale and the Institute of Global Affairs. You know better than anyone about diplomacy versus military action. I always say that military action is the final arm of diplomacy but you understand the risks and the opportunities that are associated with both military action and prolonged diplomacy. When you look at these threats, Russia, China and unknown terror networks that may be out there that we don’t even know we’re in this fight with, where do you believe the focus needs to be? What are the vulnerabilities that we have to quickly conduct these AARs and say, “Apply focus here now.”

I would take issue with you saying that I’d know better than other people. I wouldn’t but I feel strongly that you’ve got the military capacity and the diplomatic capability. I remember a quote back from my days at West Point. One of my courses said, “The purpose of the Spartan army was to give credibility to Spartan diplomacy. The purpose of Spartan diplomacy was to avoid having to use the Spartan army.”

It’s like the Mahanian fleet in being, the concept that if you have military power, it gives you the ability to influence actions whether you use it or not. If you don’t have that capacity there then you have fewer options because you’ve got no ability to threaten. At the same time, once you use it and I would argue this with the war on terror, you show your enemy how long the dog’s leash is.

How many times have you walked by a dog in the yard and suddenly hear this barking and it runs towards you but it’s chained to a pole so it stops? You’re outside of the length of that and you go, “Good.” You’re never quite so scared afterward because you know that dog can’t reach you. There’s a limit to all military capacity. Once you use it, you essentially demonstrate its limitations.

The apogee of American power was probably after the first Gulf War. We convinced the world we were a hyperpower and we could feed in because we beat Saddam Hussein’s vaunted legions, which wasn’t that hard. The bottom line is we used it, we stopped and we people felt, “These people can militarily do anything.” By far, our greatest risk is not our military capability. Although we are being threatened in areas where we’ve got to focus and build hypersonic weapons but some other things in cyber and whatnot. We’ve got to increase our capability because if you don’t stay at least at parody there, you take yourself out of the game.

The number one threat that is us now is our own dysfunction. If I was a foe of the United States, I would watch our news and I would conclude that we can’t make decisions on what to have for lunch. That’s because we have confused a two-party system with war. The importance of a two-party system is that nobody can win completely or you destroy the thing you rely on, the two-party system, which keeps you from going to the extremes. If you have a winner take all mentality then either party tries to take all you’re trying to defeat or destroy the one thing you’re dependent upon, which is this two-party system.

The first thing is our own and I’m going to call it not political at the national level but dysfunction and tribalism in our society now. People look at us and they don’t think that they are facing a united America. They’re facing this thing that if they step back and watch long enough, we’ll tear ourselves to pieces. The truth is, we might. I hope that that does not happen but it’s possible that we are losing so many of the things which we all agree on as being critical. Instead, we’re leaning toward the things which divide us that we are going to look at as a group of entities, not as a single united nation. That is terrifyingly weak.

You step past that to the kinds of threats that are real to us in the near term. Information is the first and that is aided by improved information technology now. If I drew a scenario for you on the eve of a political election, a story was put out about Lisa Jaster who’s about to be elected president. The story could be completely wrong but it comes out the day before the election. A huge percentage of people go into the voting booth wondering if you have stolen all this money or done the horrendous things that the story has.

Maybe it comes out that says, “That was completely untrue. That was fabricated.” You can’t undo that. There’s always a group of people who are going to keep believing in it anyway. The ability for disinformation, misinformation which I say is unintentionally false but disinformation intentionally, you can change the attitudes of populations almost on a dime. You can do it fast, inexpensively and convincingly that we are vulnerable to it.

If somebody went after any 1 of us 3 and decided to do character assassination to amuse themselves, they could tie our lives in knots. You extrapolate that to the national level and that’s scary. You step one from that and you go to cyber. The problem with cyber is the thing that makes our lives what it is now, the interconnectedness is a source of incredible vulnerability. My wife and I bought a new refrigerator and it’s on Wi-Fi. I go, “Is it going to send me an email?” If I get one from the refrigerator, I’ll be concerned.

“You’re low on milk.”

The idea is we’ve got many points of entry and many points of vulnerability. If American society lost its cyber connectedness, our society would be torn apart in 48 hours. If you couldn’t bank, if you couldn’t do things, you would revert to a post-apocalyptic set of behaviors. You would hoard everything, you would have shotgun shells and whatnot and you and your family defending the homestead. That could happen pretty easily. You take one step from that and you go to our power systems or the distribution of fuel or food.

[bctt tweet=”If you peel back the stories so far that you try to find every flaw, the reality is you take away from the importance of the message.” username=”talentwargroup”]

We have such interconnected dependencies on all the things we live for our society to work, to function at the basic level that it is extraordinarily vulnerable to any attacks or malfunction. Maybe someone doesn’t attack it. It breaks somewhere. Those things are good. I’m not arguing to do away with technology or connectedness but we need to look at the resilience of that to natural disaster, to external attack, to stupidity on the part of an operator and that thing. All of those things threaten the existence and functionality of our nation as a society. Without those, everything else is small stuff.

You referenced in the book a bit about where we are in America and where we have to go. This is our Veterans Day discussion. America is a place. We can view it on a map. We live here but more importantly, America is an idea. It’s an idea of freedom, opportunity, equality and hope. It is a tough time, everything about COVID, racial tension, hyperinflation, the political divide.

On the horizon, I don’t think we talk about it enough but there’s a generational shift and leadership coming in this country. The leaders who have been in power for over 50 years of our political system are soon going to become out of power. Who’s going to fill that void? Who’s going to fill that gap? That’s such an unknown that it almost becomes scary if you start to think about it.

Also, I think about change. Change must first begin with an honest assessment of who we are in a demonstration of humility as we talked about. After you understand who you are, you have to make a commitment. There’s got to be a willingness. Can I believe that I can make a change if I simply motivate myself enough to take the first step? It doesn’t have to be a big step, just a first step in some direction.

In the book, you referenced The Alamo. You said, “The crumbling old mission communicates values of selfless sacrifice and unwavering commitment to a greater cause. It reflects brightly how Americans want to see themselves and to be seen by the world and has carried almost a magical force for nearly 200 years.” We sit on Veterans Day. We honor those who have served and fought for our nation. How do you think about Veterans Day? How do you think about America? You spoke a lot about the things you have to do in terms of risk and the security piece. As a culture, what do we do to come together?

First, I would describe America as a promise. It was a promise that if people came together and if they united and stuck together, they could create something better than what they had, the thirteen colonies under British control. Ever since that, it’s often an unfulfilled promise but it has been a promise that we can be stronger, more prosperous and safer if we unite.

What that promise also means is that each of us makes a promise. It says that if we are willing to do those things to make fellow Americans more secure, willing to sacrifice, willing to serve, put ourselves at risk, pay taxes, all the things that are inconvenient and difficult, that we will get in return the promise of opportunities, justice and security that come with that. It’s a covenant among people that do that. It’s been pretty beneficial to the members. You get more from it, I would argue. Usually, you have to commit all the people who have given their lives because they felt it was important to maintain this.

You are a graduate of West Point, the Naval War College, you’ve done fellowships at Harvard in the John F. Kennedy School of Government in the Council of Foreign Relations. You teach at Yale and the Institute of Global Affairs. You know better than anyone about diplomacy versus military action. I always say that military action is the final arm of diplomacy but you understand the risks and the opportunities that are associated with both military action and prolonged diplomacy. When you look at these threats, Russia, China and unknown terror networks that may be out there that we don’t even know we’re in this fight with, where do you believe the focus needs to be? What are the vulnerabilities that we have to quickly conduct these AARs and say, “Apply focus here now.”

I would take issue with you saying that I’d know better than other people. I wouldn’t but I feel strongly that you’ve got the military capacity and the diplomatic capability. I remember a quote back from my days at West Point. One of my courses said, “The purpose of the Spartan army was to give credibility to Spartan diplomacy. The purpose of Spartan diplomacy was to avoid having to use the Spartan army.”

It’s like the Mahanian fleet in being, the concept that if you have military power, it gives you the ability to influence actions whether you use it or not. If you don’t have that capacity there then you have fewer options because you’ve got no ability to threaten. At the same time, once you use it and I would argue this with the war on terror, you show your enemy how long the dog’s leash is.

How many times have you walked by a dog in the yard and suddenly hear this barking and it runs towards you but it’s chained to a pole so it stops? You’re outside of the length of that and you go, “Good.” You’re never quite so scared afterward because you know that dog can’t reach you. There’s a limit to all military capacity. Once you use it, you essentially demonstrate its limitations.

The apogee of American power was probably after the first Gulf War. We convinced the world we were a hyperpower and we could feed in because we beat Saddam Hussein’s vaunted legions, which wasn’t that hard. The bottom line is we used it, we stopped and we people felt, “These people can militarily do anything.” By far, our greatest risk is not our military capability. Although we are being threatened in areas where we’ve got to focus and build hypersonic weapons but some other things in cyber and whatnot. We’ve got to increase our capability because if you don’t stay at least at parody there, you take yourself out of the game.

The number one threat that is us now is our own dysfunction. If I was a foe of the United States, I would watch our news and I would conclude that we can’t make decisions on what to have for lunch. That’s because we have confused a two-party system with war. The importance of a two-party system is that nobody can win completely or you destroy the thing you rely on, the two-party system, which keeps you from going to the extremes. If you have a winner take all mentality then either party tries to take all you’re trying to defeat or destroy the one thing you’re dependent upon, which is this two-party system.

The first thing is our own and I’m going to call it not political at the national level but dysfunction and tribalism in our society now. People look at us and they don’t think that they are facing a united America. They’re facing this thing that if they step back and watch long enough, we’ll tear ourselves to pieces. The truth is, we might. I hope that that does not happen but it’s possible that we are losing so many of the things which we all agree on as being critical. Instead, we’re leaning toward the things which divide us that we are going to look at as a group of entities, not as a single united nation. That is terrifyingly weak.

You step past that to the kinds of threats that are real to us in the near term. Information is the first and that is aided by improved information technology now. If I drew a scenario for you on the eve of a political election, a story was put out about Lisa Jaster who’s about to be elected president. The story could be completely wrong but it comes out the day before the election. A huge percentage of people go into the voting booth wondering if you have stolen all this money or done the horrendous things that the story has.

Maybe it comes out that says, “That was completely untrue. That was fabricated.” You can’t undo that. There’s always a group of people who are going to keep believing in it anyway. The ability for disinformation, misinformation which I say is unintentionally false but disinformation intentionally, you can change the attitudes of populations almost on a dime. You can do it fast, inexpensively and convincingly that we are vulnerable to it.

If somebody went after any 1 of us 3 and decided to do character assassination to amuse themselves, they could tie our lives in knots. You extrapolate that to the national level and that’s scary. You step one from that and you go to cyber. The problem with cyber is the thing that makes our lives what it is now, the interconnectedness is a source of incredible vulnerability. My wife and I bought a new refrigerator and it’s on Wi-Fi. I go, “Is it going to send me an email?” If I get one from the refrigerator, I’ll be concerned.

“You’re low on milk.”

The idea is we’ve got many points of entry and many points of vulnerability. If American society lost its cyber connectedness, our society would be torn apart in 48 hours. If you couldn’t bank, if you couldn’t do things, you would revert to a post-apocalyptic set of behaviors. You would hoard everything, you would have shotgun shells and whatnot and you and your family defending the homestead. That could happen pretty easily. You take one step from that and you go to our power systems or the distribution of fuel or food.

[bctt tweet=”If you peel back the stories so far that you try to find every flaw, the reality is you take away from the importance of the message.” username=”talentwargroup”]

We have such interconnected dependencies on all the things we live for our society to work, to function at the basic level that it is extraordinarily vulnerable to any attacks or malfunction. Maybe someone doesn’t attack it. It breaks somewhere. Those things are good. I’m not arguing to do away with technology or connectedness but we need to look at the resilience of that to natural disaster, to external attack, to stupidity on the part of an operator and that thing. All of those things threaten the existence and functionality of our nation as a society. Without those, everything else is small stuff.

You referenced in the book a bit about where we are in America and where we have to go. This is our Veterans Day discussion. America is a place. We can view it on a map. We live here but more importantly, America is an idea. It’s an idea of freedom, opportunity, equality and hope. It is a tough time, everything about COVID, racial tension, hyperinflation, the political divide.

On the horizon, I don’t think we talk about it enough but there’s a generational shift and leadership coming in this country. The leaders who have been in power for over 50 years of our political system are soon going to become out of power. Who’s going to fill that void? Who’s going to fill that gap? That’s such an unknown that it almost becomes scary if you start to think about it.

Also, I think about change. Change must first begin with an honest assessment of who we are in a demonstration of humility as we talked about. After you understand who you are, you have to make a commitment. There’s got to be a willingness. Can I believe that I can make a change if I simply motivate myself enough to take the first step? It doesn’t have to be a big step, just a first step in some direction.

In the book, you referenced The Alamo. You said, “The crumbling old mission communicates values of selfless sacrifice and unwavering commitment to a greater cause. It reflects brightly how Americans want to see themselves and to be seen by the world and has carried almost a magical force for nearly 200 years.” We sit on Veterans Day. We honor those who have served and fought for our nation. How do you think about Veterans Day? How do you think about America? You spoke a lot about the things you have to do in terms of risk and the security piece. As a culture, what do we do to come together?

First, I would describe America as a promise. It was a promise that if people came together and if they united and stuck together, they could create something better than what they had, the thirteen colonies under British control. Ever since that, it’s often an unfulfilled promise but it has been a promise that we can be stronger, more prosperous and safer if we unite.

What that promise also means is that each of us makes a promise. It says that if we are willing to do those things to make fellow Americans more secure, willing to sacrifice, willing to serve, put ourselves at risk, pay taxes, all the things that are inconvenient and difficult, that we will get in return the promise of opportunities, justice and security that come with that. It’s a covenant among people that do that. It’s been pretty beneficial to the members. You get more from it, I would argue. Usually, you have to commit all the people who have given their lives because they felt it was important to maintain this.

That idea is being challenged. There is an idea that we have a different view of what America is and different parts of our society that are distinctly different enough that it’s hard to say, “That promise applies to me.” I view it differently from you that we’re not aligned on willingness to sacrifice and willingness to do those things because I don’t agree with that promise as you do. That is scary.

When I talk about The Alamo, what’s important is there’s a lot of complexities to the reality of The Alamo. There are a lot of arguments that the defenders were trying to position Texas to be another slave state. There were probably some nefarious characters and 180-plus people that were there. That doesn’t matter.