Some organizations are so vast, so large, and so dynamic that it is often almost impossible to comprehend the scale and complexity; making leadership the most important factor in performance.

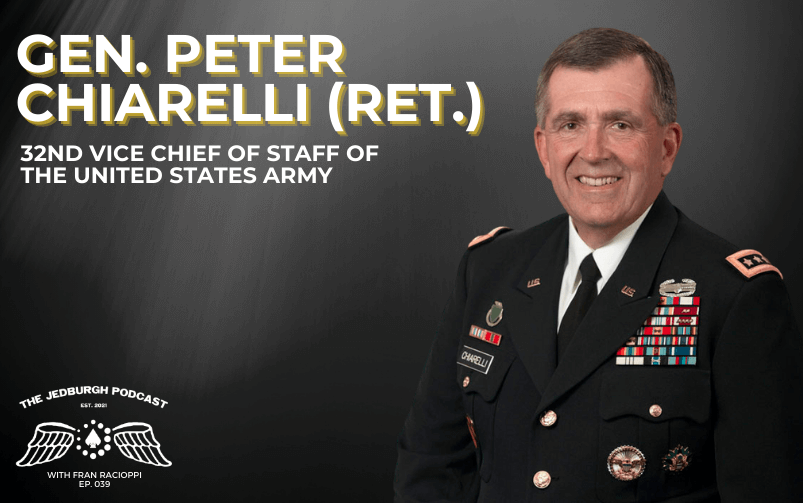

General Peter Chiarelli served as the Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army, an organization of over 1.1 million employees and a budget of $240 billion dollars. General Chiarelli is one of our nation’s most innovative leaders; always challenging the way the Army operated. He transitioned the Army from Vietnam, through the Cold War and into the modern Army of today.

General Chiarelli and Host Fran Racioppi discuss the General’s career, his days as a professor at West Point, how he led the medical industry in changing the way we view post traumatic stress, how COVID has set the example for collaboration and teamwork, the importance of wearables in tracking our health, the lessons of the war in Iraq, and what type of leaders we need in our nation today.

—

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

—

I’m joined in this episode by retired Four-star General Peter Chiarelli. He served as the Vice Chief of Staff of the United States Army, an organization of over 1.1 million employees and a budget of more than $240 billion during his tenure. He is highlighted in the history books as one of our nation’s most innovative leaders. He’s always willing to challenge the way the Army operated to unlock the driving factors of why. His curiosity and humility transitioned the Army from Vietnam to the Cold War and then to countering surgency encounter terrorism battles we fight today.

General Chiarelli commanded 20,000 soldiers in the Iraqi capital of Baghdad in the early days of the war. He later led over 150,000 people across Iraq during one of our military’s most complex and challenging times. He served as a scholar at West Point and a Senior Military Advisor to Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. Now, he continues his mission to support our troops as he pushes the medical industry to work together to treat traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress.

He advocates for wearable technology and treatment and he knows firsthand the effects of over decades of combat on our military members. We cover all of this in our conversation and the next battles we have as Americans both abroad and at home. An eternal optimist, he and I share a passion for driving others to be their best, no matter the challenge.

—

General Chiarelli, welcome to the show.

It’s great to be with you.

Challenging the status quo, asking hard questions, forcing others to think about how and why, most importantly, why they do things are critical skills for leaders in any organization. This show is built on taking the nine characteristics of elite performance, drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, curiosity, team ability, effective intelligence and emotional strength, and then tying them into the stories of our guests.

These come from the nine characteristics that Special Operations Command uses. It doesn’t matter whether you’re a Green Beret, Navy SEAL, or an Army Ranger. They weigh them differently and use them to assess, select and then train all of their talents. Most people don’t realize that the best leaders exhibit these traits, but they draw them out in their teammates, peers, subordinates, and superiors. You achieved the highest military rank possible and commanded the US Army.

I think about that for a second. You commanded all of the Army in addition to all of the units that you commanded as you were moving up through the ranks. You led hundreds of thousands of service members across all branches in Iraq at one of the most tumultuous times. You transitioned the military from a Vietnam Relic to a cold war superpower to a counterinsurgency force for good. You did it by questioning everything, even when you knew you didn’t like the answer.

I think about it in terms of these nine characteristics. I think about curiosity pushing and challenging the status quo. I also think about humility because you were willing to accept that we may not always have the right answers. We have to adapt and change. When we do these shows, sometimes we tell the whole story of our guests. Sometimes we tell a little piece and only talk about an initiative they’re working on. I only think it fits you that we have to start at the beginning.

Your career started in ROTC in Seattle in the mid-1970s. Vietnam had been going on for a couple of years. You entered the Army willingly towards the latter part of the war, which was not a popular choice amongst your peers, especially in the liberal Northwest. ROTC meetings were held in secret. You couldn’t wear your uniform in public, but your father served in World War II as a tanker. You’re you like me are of Italian descent and your father, like my father said, “Yes, I support you going into the Army, but you’re going to go to college first and go in as an officer.”

I would say that now, and probably because of you, we support our military. It’s so much different than the times were back then. In fact, we revere and respect the soldiers in the service members, even if we don’t agree with the politics and the policies. What was it like in that period of entering the Army? You’re a young officer. It’s a formative year. If I think about my time as a second and first lieutenant, that shaped you in so many ways for the rest of your career. Your dream was to become a lawyer, but you ended up going into the Army during this time. Talk to me a little bit about what that was like.

It was a difficult time. I remember going to my father when I was about ready to graduate from high school and saying, “Dad, I’m going to go see a recruiter and join the Army.” I feel that I need to go serve my country. Remember, I grew up in a town at that time. Seattle wasn’t as liberal as it is now. It had 3 or 4 different bases scattered around town, Navy, Naval Air and Army. It wasn’t a military-type town. I grew up around World War II vets.

When I went to my dad and told him that, he understood, but he looked at me. He got about his cross as he ever got with me at any time and said, “No, you’re not. No one from this family has ever gone to college. You’re going to go to college. If you want to join the Army, get into an ROTC program and go through ROTC, and enter that way.”

[bctt tweet=”The essence of team building is the ability to listen and not be in transmit mode all the time.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I wasn’t used to saying, “Dad, you’re wrong.” He was my hero. I listened, and that’s exactly what I did, but I remember it was difficult. ROTC, we got a call at 5:30 in the morning, and we were told 1 of 3 different places to show up for drill. The drill would last for exactly an hour, and we’d be out of there before the protestors could catch up with us. We didn’t wear uniforms.

When the first lottery was held toward the end of the Vietnam War, I prayed that I would get a low number so that I could rationalize to my friends why I joined ROTC and lo and behold, I got 276. I would not have had to enter the Army under the lottery if it had ever been implemented. You did those kinds of things because it was not a popular profession at that particular point in time.

You go in and spend your initial first four-year commitment and then submit your resignation papers to get out. How come?

My wife grew up in Portland, Oregon. I grew up in Seattle, Washington. I grew up in the same neighborhood. I lived in the house for a couple of years when I was a young kid, but I don’t remember it. I remember living in a single house, going to Magnolia Grade School, which I walked to Catherine Blaine Junior High and Queen Anne High School a little bit over a mile.

I envisioned the same life for my kids, and so did my wife. We had our first child and could not imagine that we would enter into a profession that would see us moving every couple of years all around the country and, quite frankly, the world. I wanted to go to graduate school. I had something to prove to myself when I did not get into law school, one of life’s great lessons.

I could not get in because I had a low SAT score. I felt that I could do important things. I wanted to prove to myself that I could go to school and get better grades than I had as an undergraduate. The job opportunity gave me a chance to go to school. It wasn’t until the Army countered with an opportunity to go to a two-year fully funded graduate school onto West Point to teach. I hardly even knew where West Point was going up in the Pacific Northwest. It was too good a deal. We decided that if we didn’t like moving, we would go ahead after our West Point commitment was finished, but that never happened. I came in for four, and it ended up being almost 40.

In business, that’s a good return on investment.

They had all the hooks in me. They sent all the right things at the right time and offered the right things.

That’s what they do if you think about your whole career. As you’re talking about it, I think about mine. You’re a lieutenant, and then everybody comes to that decision. I think every lieutenant has that conversation, and they’re like, “I can go to the FBI, agency or somewhere else.” I even remember I was in Iraq as a first lieutenant in 2005, 2006. I was like, “My dad had talked to me about the Coast Guard. That’s a good job.” I’m sitting in my room. We’re getting rocketed. I’m thinking, “If I was a Coast Guard pilot, I could live on the water and fly helicopters. How do you branch transfer?”

I remember I looked it up and had a call with a recruiter from the Coast Guard. He had told me that they had filled their cross-branch quota for ten years. I thought I had this revolutionary idea, but then they did. They come back and are like, “If you stay in, here’s what you’re going to get. You’re going to go do these jobs.” Even though in the back of your mind, that’s a real big hopefully if I get to do those things, and then you look at getting out. It’s like, “No, I’m going to go try to do those things.” You ended up staying in time and time again.

I remember getting a call from a branch manager at one time that said, “I’m going to tell you something now, and you should go call your mother and tell her what a great job you’re doing in the Army. You’ve been hand-selected to go to Korea on an unaccompanied tour for one year. That does not happen to too many folks, and you’re one of them. Call your mom right now and tell her.” When I became vice chief of staff, I had an opportunity to work with some of these personnel guys. I said, “Do you guys use that tactic? Was that as nefarious as I think it was in hindsight?” They said, “Yes, that’s what we have to do. We’ve got a tough belly to fill. Call your mother.”

You stay-in and went to West Point and had an opportunity to join the Department of Social Sciences. You and I are not a West Point guy. I didn’t even know there was such thing as this Department of Social Sciences. I read about it. You and General Petraeus went there. Many of our nation’s greatest leaders have been in this department. Can you talk a bit about that teaching experience? Why does this department breed this level of leadership that has gone on to command at the most senior levels? I know there are so many more that have served in there.

It does a fantastic job of sending people to graduate school all over the country. If you want to go to Princeton, you can go to Princeton. If you want to go to Harvard, you can go to Harvard. I had not been allowed to go to the University of Washington because my mother said, “It was too big.” I went to a small Liberal Arts Jesuit university called Seattle University. All I wanted to do was go to the University of Washington and prove my worth. It takes folks from all over. It gives them a two-year, fully-funded graduate degree. It has great leaders.

Jim Golden was one of those leaders I knew while I was at West Point, who became a brigadier general. I had an illustrious career at William & Mary. The head of the department was a guy named Don Olvey, who was an amazing man with an amazing family. He gave us all the opportunities to take the two-year fully funded education we’d had and explore things we wanted to explore.

When you bring together a bunch of bright lines, I wasn’t necessarily the brightest mind back there, but I worked harder than anybody else. When you bring them all back together, you get a copy of the New York Times every day. You do things like a caption contest where you post something on a bulletin board and have an opportunity to talk with folks that have been educated all over the country. It breeds the leadership cauldron we had in the Department of Social Science. I learned so much when I was back there from so many different people, including Dave Petraeus, Doug Lute, a guy named Pat, who left us far too soon. It was an amazing opportunity.

You were there at such an interesting time too. We’re coming out. Vietnam’s over, but now there’s the after-action review time, all the lessons learned, what do we have to accept? What went wrong? What went right? How are we going to move forward? I want to ask you about General Colin Powell, but now there’s this emerging theme in the Army of the transition into the Cold War. It eventually became known as the Powell doctrine. If we’re going to get into conflict, we’re going all in.

I busted in the house because I was running late to get back here after dropping my son off. My wife said, “Storming Norman.” I looked at her and said, “Storming Norman. That’s fitting because I’m talking to General Chiarelli, who probably knew General Schwarzkopf.” She said, “I don’t know what that means.” I’m like, “Storming Norman, that’s the nickname they gave to Norman Schwarzkopf in the Persian Gulf War because he, like General Powell, was all about force. When you go in, use force. You’re there at this time when the Army has to start to think about what this transition looks like?

It was a difficult time. My first four years in the military were a difficult time. We had all the issues that you’ve read and heard about, race relations and drug issues. We were trying to institute a professional army and move to an all-volunteer force. That was a difficult time to come back to West Point during that time and talk with other folks that had similar experiences.

Literally, the Department of Social Sciences reached out and grabbed the best and the brightest, but I was grabbed because of a cheating scandal that occurred at West Point in ’76 or ’77. There was this commission set up, run by Frank Borman, who was one of the early astronauts. He said, “West Point is too in a breath.” It gave me my opportunity because they hadn’t invited a lot of ROTC and OCS folks to come back to West Point to teach.

Normally you went through school, the department that you were the best in, and made a little note that 3 or 4 years into this, we might ask this kid if he wants to come back this young lieutenant and teach here and give them the same opportunity I had. I was asked to come back because the Borman Commission said what it said. You need to reach out and grab not West Point graduates. You need to grab other folks who have done well in the Army.

That’s exactly what happened to me. If it hadn’t been for a mentor of mine named Ron Adams, who later became a lieutenant general, I would not have had that opportunity. When I went into him and said, “I’m going to leave the service after four years. I’ve accepted a job in Portland, Oregon.” He said, “Come back in two hours and give me this offer,” it would not have happened.

The biggest lesson that I learned at West Point was that the Department of Social Sciences was a team. It was all about team-building. We had so many things on our plate like extracurricular activities that had to be done, conferences that had to be held, and other things, plus the opportunity to write. That’s what kept me there for the fourth year was an opportunity to work with some colleagues and publish a book.

It taught me a lot about teamwork, which became the centerpiece of my Army career moving forward. It’s the ability of a team to do things that no single individual could do on its own. It wasn’t about individual leadership as much as it was. How do you bring together a whole bunch of smart folks? Somebody has got to lead in different instances. How do you do that and get everybody to contribute and get the most out of them? To me, that was the big lesson I had coming out of West Point.

This diversity of thought that you’re talking about is important in building organizations. When we had General McChrystal, we spoke a lot about this. We think about diversity so many times in all sorts of organizations. We think, “I have to get people of different ethnic backgrounds. They have to be of a different color. I need men and women,” but the reality is if you can do that. If everybody went to Harvard or West Point, they might look different.

They may have had different life experiences, but they’re still thinking the same. How do you challenge that? The greatest organizations and teams focus on the diversity of thought in the organization. We’re driving collaboration, but there’s a level of dissension and a little bit of that constructive argument that happens.

That’s what we saw every single day in the Department of Social Sciences during the four years I was there. I took those lessons learned for my first assignment in Europe, the power of the team, how to build a team, and bring together people to do something that maybe no one has ever done before.

You did that when you went to Europe and won the gunnery challenge.

It’s the Canadian Army trophy. I took the lessons learned I learned at West Point and put together a team to do something in the United States Army that had never been done before. It was a direct product of that experience at West Point. We built a team and did everything we could to ensure that team was successful, and that meant listening to your soldiers and being willing to change course.

You listened to something that made a heck of a lot of sense that you may not have realized was it was impactful. I remember at one particular instance. We were limited to the number of rounds we could fire in the train up, which was a fourteen-month train up for this big gunnery competition. If I remember right, 120 rounds. It was not very many. At the same time, this was the revolution in training that was occurring gunnery traders that were coming on board. There was one for the Armor Force and a Mounted Infantry Force called the UCOFT, Unit-Conduct of Fire Trainer. It was branded.

It would seem medieval if you were to compare it to what you can get on your phone now, but it was huge. Everything in it was exactly like sitting in a tank, the switches where they were supposed to be. We called Switchology. You did all those things. You had somebody who was looking over your shoulder, and you fired different scenarios. What we used to do is when somebody missed a particular engagement with a live round is we pull them off the range, stick them in a UCOFT, and see if we repeat that engagement a whole bunch of times. We stick them back on the tank and see if they could hit the moving target at 1,500 meters while on the move.

We did get good results. I had one kid come up to me, and he said, “Sir, you’re not getting good results. When you move from the tank into the UCOFT, you’re moving from something hydraulic controlled to something that’s electrical control. The instruments work differently. My Cadillac works differently and moving that gun tube around. I think it would be helpful if we went into the UCOFT. I think that’s a good thing.

After we get out of the UCOFT, which is electrically powered, go onto a tank and do a simple thing called a snake board where you get on and take those Cadillacs. You traverse that gun around it, looking through the site, you traverse it on aboard. He said, “I think we’ll do much better because it’ll get us used to the hydraulic controls after being with the electrical controls.” We did it. It worked. That was a PFCs and major’s idea. It was listening to your soldiers.

[bctt tweet=”We are all genetically different and these things affect us in different ways.” username=”talentwargroup”]

That’s so important in leadership. When I talk to a lot of folks in the private and the civilian sector, and I speak about my time in the military, they often will think that “You sit around and wait to be told what to do.” There’s this hierarchy of command. The commanders come in, and they sit around and say, “Do this in this way, and you have to execute.”

I always tell them that the military as much as the hierarchy exists, and there are those days what we would call waiting on the word, usually to go home. More often than not, it’s that bottom-up feedback that leads to innovation. At the top, the commander, when you’re in charge, the CEO or a director in a company, you don’t always know better. All the information that has to go into making the best decisions, when you can sit back and take that bottom-up feedback, your ability to innovate and move much further and faster is much more enhanced.

I couldn’t agree more. That’s exactly to be the essence of team building. It’s the ability to listen and not be in the transmit mode all the time. It is so true. It’s almost trite to say you never learn anything when you’re talking. There comes the point in time when you have to make a decision. If I move that forward to the work I did in traumatic brain injury when I was vice chief of staff, that was the same thing. I had no idea what traumatic brain injury was.

I knew what my football coach had taught when I got bounced on the head, “Shake it off, and got back in the game.” I had no idea what post-traumatic stress was. When faced with these huge problems that were facing the Army, when I became vice in 2008, given the numbers that we had, I applied the same lessons learned at West Point when we were training for the Canadian Army trophy to understanding something that I did not understand nor did too many other people.

You became the 32nd vice chief of staff of the Army. It’s the second-highest position in the US Army. It’s the second time that you worked for General George Casey, and you were under him in Iraq as well. You held this position for three and a half years. I think about this, which is the pinnacle of every Army officer. Every Army officer looks at this and says, “I can’t wait to get there.” It’s so difficult. I think for people also to rationalize that scope, but I was looking at your LinkedIn.

I chuckled a little bit when I read the description when you have your role, and I’ve got to read it because it says, “The COO of an organization of 1.1 million men and women with a yearly budget of $240 billion.” You look at it on LinkedIn, and you’re like, “Okay.” It’s like, “It’s 1.1 million people with a yearly budget of $240 billion. This is one of the largest and most complex organizations in the world.

I have to say that budget was inflated at the time because of what we call OCO money. The Army had a whole bunch of extra money given to support the other services in the two wars we’re in. I had about $100 billion added to my base budget of $140 billion, but it was $240 billion. That in itself created a whole bunch of issues. It was a huge job. Normally, you only come into that job for about a year, and they move you out to do something else. They decided they were going to have to leave me long until I finally got a few things right. It ended up being over three and a half years.

The biggest pillars are the things that you focused on during your time as the vice chief was first on the military healthcare system, and secondly, on the development of the next generation of Army leaders. When we look at the military healthcare system, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, they injected into the military healthcare systems so many different types of injuries, combat-related and non-combat related injuries, that I think we were so in a way unprepared for institutionally.

I think from a medical standpoint, certainly, the military, in many ways, leads some innovation in the medical field and point of impact trauma. How do you treat these people in long-term care systemically over time? It seemed like we were still resting so much on the Vietnam era or the Vietnam thought process. The VA was still so many decades behind a civilian healthcare system.

When we first spoke, you told me that during that time, 32% of those classified as wounded suffered from TBI, Traumatic Brain Injury or PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, 62% of the most seriously wounded people were in that 32%. Yet, as you said, in 2008, 2009, we all knew almost nothing about TBI or the long-term effects of PTSD. What, at that time, did we know? When you assumed the position of the vice-chair, how did you assess the situation and then say, “Yes, this is what we have to focus on, and this is where we have to go.”

We didn’t know a heck of a lot. I often look at criticism that the NFL has had that you should have known the impact of football and some of the traumatic brain injury that has suffered there. You should have known it. Frankly, we did not know it. Like I said before, I only knew what my football coach had told me about a concussion, “Shake it off, get back in the game. You’ll be fine.”

When I asked a question about concussions, I had senior medical officers tell me what are the long-term impacts of concussion? Look at me and say, “I grew up playing rugby. I’ve had six concussions before I ever entered the Army. I’m one of the most successful surgeons in the United States Army. You don’t have to worry about concussions. People recover from a concussion, and there is no long-lasting impact.” Nothing could become further from the truth for some people.

We are all genetically different. These things affect us in different ways. I don’t need to repeat to you the different diseases that run in families based on their genetic makeup. The fact of the matter is the same for concussions. I couldn’t get the answers that I needed listening to my doctors in the Army. I had to reach out to civilian doctors, which proved to be the people I needed to listen to. It wasn’t just me.

My counterpart, Jim Amos, who at that time was the Assistant Commandant in the Marine Corps, had seen the same issue with Marines. The two of us went on a journey to try to learn everything we possibly could, which caused us to have to listen to a whole bunch of different people and finally make some decisions on where we were going to go. People don’t normally like to question doctors. They’re always seen as the smartest person in the room.

When they say it, and they say it with authority, the tendency is to say, “That must be the case because that’s what the doctor said.” When we looked into it, we found out that there were folks who weren’t necessarily in our sphere of influence that was outside of the Army, who could help us with this problem that we were seeing.

The numbers were huge. I had expected to see those who lost arms and legs and were wounded to be the biggest group that had a single VA disability of 30% or greater. It wasn’t even close. They were running at 11%. In 2008, combined traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress was 32%. When I left three and a half years later, it was 64%.

There’s some big spectrum, too, when you talk about PTSD specifically. There’s this stigma that lives around this where people think, “If you have PTSD, you see dead people, have all these visions, can’t function, and you sit there in your chair and convulse.” That’s not true. For some people, it is. Those cases are rare. They’re extremely sad and debilitating for the people who suffer from that.

There is a stigma around that. It’s not the reality for the majority of those that suffer from it. I’m interested in this because to combat this stigma. You started dropping the word disorder from PTSD and calling it an injury. The civilian medical industry did not immediately pick up this train of thought. They continue to call it a disorder, but you said, “You don’t want to be labeled with having a disorder. We consider it honorable for people to get help with the visible wounds of war. Why wouldn’t we consider it honorable to get help with the invisible wounds of war?” I think that’s a profound statement.

You said so much there that I want to unpack. First, this word stigma is absolutely critical. You say we had never been faced with these problems before. We’d always been faced with these problems before. If you look back into Greek mythology, you could see instances where people talked about post-traumatic stress and traumatic brain injury without calling it that.

These were problems that came with war. We swept these things underneath the carpet, and we did it because of the stigma associated with them. If there’s anything that Jim Amos and I were able to do was to make it was okay to talk about traumatic brain injury or post-traumatic stress. The thing that gave me the ability to do that was a great doctor at UCLA named David Hovda.

He brought me a single slide, which proved pivotable, with me telling a story to units before they deployed. It showed three brains. The pictures of brains were taken using something called positron emission tomography. All of it was a new way of doing, for lack of a better term, taking a picture of the brain where you pumped sugar into the body and saw the brain light up. The brain is a small organ, but it burns 20% of the energy created by the body.

Most people don’t understand that. When it’s functioning the way it’s supposed to function using positron, emission, tomography, and taking a picture of the brain, all you see are reds and yellows. The three pictures were a normal brain that looked all red and yellow, and two other brains. They looked almost the same.

One was an individual who’d been in a car accident and comatose for five days. They pumped him full of sugar, took a picture using positron emission tomography, and that picture looked exactly the same as the middle picture, which was of a UCLA football player, injured with 1 minute and 12 seconds to go in the first half, cleared at half time to play the second half. He played the second half, but the trainer came up to him and said, “You took a big hit to the head, and sometimes concussions don’t produce symptoms for up to 24 hours. If you have any of the following symptoms, I want you to go see the doctor first thing tomorrow.”

He woke up, had the symptoms, went in, and told the doctor what the problem was. They took a picture of his brain using positron emission tomography. I challenge anyone to tell me the difference between the brain of the individual who had been comatose for five days, as opposed to the brain of a football player who walked in 24 hours after the event said to his doc, “Doc, this is what I’m feeling right now. I was told to come to see you in the event that I had these symptoms.” It was a stigma. It was trying to combat stigma.

When I had that slide, I could prove to a young kid, “What your football coach told you wasn’t necessarily the case. When you get smacked on the head, it’s not necessarily always something you can shake off and get back in the game. You need to go seek the appropriate help, talk to somebody and let’s see what we can do about it.”

These injuries affect not just service members. We spoke on a previous episode with the NFL wide receiver, Austin Collie. Austin Collie was the poster child in the NFL for traumatic brain injury and potentially the onset of CTE, which comes later. He had a series of devastating hits, and this was a phenomenal athlete, who had been knocked out, spent a couple of games on the sidelines, came back in, played like two plays, and got knocked out again. This happened multiple times and someone who was in the hall of fame at BYU, recruited to play for the Colts, then went to the Patriots. Now had a career that ended up only being a couple of years because of his hits.

That’s what happens to some folks. David Hovda taught me that you could take a young lady who weighs 120 pounds and put her next to an NFL offensive lineman, who comes in at 300 and hits him with the same force to the head. The lineman, because of genetic makeup and the way his brain process that hit, is out for the count, whereas the young lady at 120 pounds who had that same hit is perfectly fine.

We don’t know everything we need to know about traumatic brain injury, nor do we know what we know about post-traumatic stress. You tell the story about me dropping the D, and that was because of a family member who came to me and said, “My husband, I know suffers from post-traumatic stress, but he won’t go see a doctor because he does not want to be branded with having a disorder.” She said, “Why do we call it post-traumatic stress disorder?”

When you look back, you find that before we got into the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, most of the research on post-traumatic stress was done on women who had been sexually assaulted. It struck me as she told me this story, and I realized the history of post-traumatic stress and the stigma that surrounded it. How could you go up to a woman who’s been violently, sexually assaulted, who has issues with relationships with men after that incident and say she has a disorder because of that?”

I made that argument to the American Psychiatric Association almost immediately after I retired. They were getting ready to publish what they call their new DSM, which is their Bible. I won’t go into that. I went to him and begged him. I said, “Please drop the D. You don’t have to call it an injury. Just say post-traumatic stress. Get rid of the D. I’m trying to give you a business. People out there are suffering from this who are not coming to see you get the help they need because 19, 20, 21, 22, 27-year-old male or female doesn’t want to be branded with having a disorder. Get rid of it. We will help get the stigma issue revolving around post-traumatic stress.”

When you frame it that way in that context with those types of victims, for sure they are, it’s almost unfair. If you think about the word disorder, to say that they have a disorder because this happened to them.

What’s unfair about it is little we know about it, yet we call it a disorder. Why would you brand it that way right out of the box when you don’t understand it? That’s probably human nature. If we don’t understand it, we decide we’re going to call it a disorder. When in reality, I don’t believe it’s a disorder at all. I believe something biologically happens to the body in some people. It happens to a different degree. There’s this other tendency to say that PTS is PTS. It’s not. It comes in different degrees.

That’s why some people can get tremendous relief from their post-traumatic stress by doing different activities that are maybe outdoors, mountain climbing, whatever it might be that helps them. There are other cases of post-traumatic stress that run much more seriously where those things may provide some immediate relief, but they don’t provide the long-term relief the individual needs.

That’s the person that I’m focused on right now. Trying to find that individual, the relief that they need through new treatments, possibly through drugs or other things that can help them get the relief they need, from what can be a disease that not only affects the individual or the whole family. That’s an important point you bring up is it affects the entire family.

[bctt tweet=”We don’t know everything we need to know about traumatic brain injury nor post-traumatic stress.” username=”talentwargroup”]

The long-term effects so many times of PTSD, TBI and these injuries that you suffer come in the form of sleep disorder, you may experience nightmares. You may experience higher levels of anxiety and emotional frustration, and because of that, now you’re not sleeping. We’ve had several conversations on different episodes about the importance of sleep. We’ve talked to Dr. Chris Frueh, who I know you’ve spoken with about Operator’s Syndrome, where we push ourselves for so long for so many years on end.

We’re always focused on the mission, but we don’t take care of our nutrition, our sleep, our mindfulness, so how do we get that back? We spoke with the Special Operations Association of America, where they’re advocating on the Hill on policy on mental health. We’ve also talked about wearables. We’ve spoken with Kristin Holmes of WHOOP, VP of Performance Science, where WHOOP is tracking so much of your vital information.

Through an analysis of your rest, it’s telling you what your workload can be the next day. We spoke with Richard Hanbury, the CEO and the Founder of Sana Health, a wearable that trains your brain pathways through light and sound. It’s training your neural pathways to understand the pain and then mitigate pain, which allows victims of nerve damage to sleep better.

They found that when you have systemic nerve damage, these elevated levels of anxiety that you have don’t allow you to sleep, leading to depression and anxiety. Eventually, it could lead to suicide or suicidal ideations. You’re doing some work right now with wearables and sleep disorders. Can you speak a little bit more about your involvement in that and the importance of sleep as a secondary effect to PTS?

I was vice chief of staff. Besides, I’m working to understand and look for therapies for traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress. I was also asked to look at the Army’s suicide rate and do everything I could to try to bring it down. We had gone from, in 2001, 10 suicides per 100,000 soldiers for the demographically corrected population. Remembering the Army was a young organization when I got out. I lowered the average age by at least three years.

We see more suicides in the younger population. What the CDC used to do is they used to demographically correct the population for us so we could see how we were doing. In 2001, we were about one-half of our civilian counterparts. By 2008, we had caught up. We had doubled our suicide rate. We were at 20 per 100,000, which was a little bit higher, quite frankly, than that demographically corrected population. I was asked to look at that.

What I heard is I had suicide cases brief to me, many of these individuals, we were able to go out and do an investigation, look at medical records, and suffer from nightmares. They would have nightmares. The reason why we knew that is because spouses would say, “He had terrible nightmares. In order to avoid those nightmares, what do you do? You drink yourself into a stupor, pass out, get a form of sleep. The nightmares don’t happen.” Quite frankly, it created another issue because, at one time, the VA wouldn’t treat anybody who had an alcohol disorder or was abusing alcohol for post-traumatic stress until they got off the alcohol. They were using alcohol to medicate themselves and help them with post-traumatic stress symptoms.

I knew that nightmares were a problem. When a young entrepreneur who had talked to a young soldier who had put together a program, an app for his dad’s Apple watch, it makes use of the haptic function on the back of the Apple watch. It’s not just an Apple watch. You could do this with any watch. The company that I’m working with is called NightWare. They use an Apple watch. It’s a specially provisioned Apple watch that collects data like I can do right now by looking at my watch and seeing what my heart rate is while you’re sleeping.

Studio portraits for SURE ID . Photo by Delane Rouse/DC Corporate Headshots.

It sends it to the Cloud, runs it through an algorithm. After collecting data for about three days, it knows based on these different things. It’s collecting off your wrist when you’re going into a nightmare. Rather than wake you up, it provides a haptic shock, so to speak, to the wrist that breaks up what’s happening enough. Not to wake you up but to pull you out of the nightmare. It doesn’t work for everybody, but it works for a large portion of folks that suffer from these serious nightmares. What I like about it is two things, in particular, number one, it’s FDA cleared. The FDA has looked at it. They believe the data supports their clearance of it to be used.

Number two, it’s not invasive, a pill or something you’re taking that is off-label prescription, a drug that was brought to market to solve another problem that in some people solves a different problem. The doctor goes ahead and provides what’s called an off-label prescription. It’s not another pill somebody has to ingest. Don’t take anything I have said as saying that NightWare is the answer to suicide. It is not. It is one contributor to helping to control some of the symptoms that I saw in my study of suicide are the ones that seem to be present at times in some people where it could provide help.

We all function so much better when we get a good night’s sleep. I believe that some of the other symptoms of post-traumatic stress appear in the daytime when you’re away. Avoidance of things that border depression can be helped by providing a good night’s sleep, not only for the individual but their partner, is critical. I’m a big fan of wearables. I think they are going to help us, not only when it comes to nightmares, but in many other areas.

I think they’re going to be particularly useful for the military population that is tired of being given a bag of pills and said, “Take these pills, and you’ll be fine.” Almost every one of the prescriptions in that bag is off-label. In fact, they all are off-label prescriptions for things that work with some people, but other people don’t.

It’s like the joke that they would tell you. They’d say, “Take two Tylenol and drink a glass of water. You’ll be okay.” The numbers on suicide, too, that you mentioned, some of them are staggering. There was a report I was reading. The USO put it out in September 2021 that said that almost 31,000 active-duty service members have died by suicide since 9/11, but we’ve lost over 7,000 to combat. That’s almost four times.

The numbers are shocking. The fact that we, as a service, haven’t done what we did when COVID first hit. I use COVID as the perfect example of how things should work when it comes to the development of treatments and vaccines. We went in nine months from not understanding what COVID was to having three highly effective vaccines. We did that, and I went back to my original theme because of teamwork. Doctors realized this was a threat to every single one of us, and rather than work for individual accomplishment, they worked together as a team.

You can read article after article about it. They broke the paradigm of how you do medical research. They worked together as a team to come up with those vaccines, told each other when they went down a road that did not work so that the other person did not rather than hope that they would, so they would spend their capital and time doing that. If we applied that same research teamwork to get at the problems of the brain, we’d be so much further along in many of the other diseases that plagued mankind.

I believe the research ecosystem has to change. It should be a shock. As a nation and world, we ought to be doing an after-action report that says, “How did we move in 9 months to 3 effective vaccines? How could we apply some of those lessons learned to the way we do medical research across the board?”

I think you nail the bit of it. You know better than almost the entire population, but this principle of war, unity of command, unity of effort is one of the nine principles of war that history shows when you apply gets it done.

When you were in Iraq and Afghanistan, at least I never entered a talk that didn’t have a sign someplace that said, “Who else needs to know?” That’s what we did. We made sure that everybody knew all those pieces of intel that were out there. Hopefully, we could avoid catastrophe. In medical research, that’s not necessarily how it works every single time. It worked, I believe that way, in developing the COVID vaccines. I wish we do the same thing across the board, particularly in the brain. The brain is a tough problem.

The fact that we’ve spent billions of dollars on post-traumatic stress research. There’s not a single drug that has come to market specifically for the treatment of post-traumatic stress leads me to the conclusion that Einstein was right. If you continue doing things the same way, time and time again, and expect a different outcome, you’re going to be disappointed.

[bctt tweet=”The brain is a small organ but it burns 20% of the energy created by the body.” username=”talentwargroup”]

You’ve talked about the DOD being pretty forward-leaning in respect to innovation and talking about these issues, bringing them to the forefront, and investing money. You’ve also said that the VA has lagged. There’s a big gap between DOD and VA. When you and I were speaking previously, even in the wearables, you said that you look at wearables, and DOD is saying, “Yes, let’s use them.” VA is saying, “No, we won’t fund them.” Can we close the gap? How do we do that?

I wish we would get leadership on both sides that realize the absolute importance of bringing the DOD and the VA together. A lot of this is based on the regulation of policy. It’s not that one organization is better than the other, but the DOD has a basic philosophy that they’ll cover anything approved by the FDA. If you’re suffering from something in DOD and it has FDA approval, go ahead and prescribe it.

In order to save money on the VA side, they have a drug formulary. They have different formularies. They’re using different things that they apply. It’s not necessarily because they’re bad people. It’s the way that Congress set up the VA. Let’s take a drug, for example. A kid finally finds the thing that works on him and helps him get over whatever the symptom it is. He leaves the service with his 90 days of that drug and shows up at the VA on the other end and says, “I’m out of this particular drug that has helped me with whatever it is I have.”

If it’s an off-label drug, the VA doctor looks at him and says, “I’m sorry. I’m not going to be able to prescribe that because it’s not on our formulary.” It was a torturous journey to get to that right drug. He or she got the right drug, and now they’re being told, as they have retired from the service, they can no longer get that drug. Many say, “Nope, I’m going to pay for it myself. I’ll go out and find a doctor who will prescribe it to me, and I’ll go ahead and pay for it myself, rather than take this substitute that the VA wants to give.”

We need to get rid of those kinds of things and understand that the individual is an individual from the time they joined the service until they die. The systems should work together to ensure that journey is similar to when you’re on active duty, seeking that same medical care and outside the service. We’re able to get NightWare covered for active component service members because of what I talked about in DOD. We are not able to get it covered in the VA, and I find that to be not a good thing.

We were coming to a point in time in which we were not at war or declared conflict. We are at war. We may not know the enemy or what the new battlefield may bring, but we’re not in a declared combat zone. We’re not in a situation where the military is dominating the news cycle. It tends to happen. I’ve had this conversation with various veteran service organizations and nonprofits, and said, “Raising money was easy for twenty years because you turned on the news, and the first thing everyone talked about was veteran-related issues and veterans in the military at war. It’s not going to be like that now.” As that ebbs and wanes, and it goes away, raising awareness for these issues, we have to continue to do that, or they’ll become overcome by other events. I think we owe it to all those that we led, served with to continue that conversation.

When I’m talking medical research, I’m a Liberal Arts Major. I still get stuff addressed to me. I came home from Thanksgiving. I found something addressed to Dr. Chiarelli. It offered me $250,000 if I signed to one of my practice. I’m not a doctor, but I learned in studying medical research. There are two kinds of people. There are your MDs and PhDs. Your PhDs are the ones that study and do the research while the MDs see patients. When you see patients, you want to help folks. As I got into this, what I was always attracted to was MD PhDs.

Those are individuals who did research and saw patients because their focus was on the patient. We need leadership in DOD and VA, that is, a VA and DOD leadership, but it’s focused on the service member from the time they enter the service until the time that we put them into the ground or they pass. We need that same focus on the service member as an individual who lives a life. That’s what has to happen. When we get that leader focused on the service member, not the individual organization, but the service member, DOD is the same after almost 40 years of service. When I left, I was Mr. Chiarelli. Now, you’re the VA’s problem. You’re no longer my problem.

I’m glad he brought up leadership because I cannot allow this conversation to end without pressing you, one of the greatest leaders we’ve had in the military. I could not have to press you on some leadership stuff. I would argue that you may not have the paper that says it, but you certainly have an MD PhD in leadership at all levels of command. In March 2004, you were the Division Commander of the First Cavalry Division, an organization that, back in the frontier days, rode horses, wore Stetsons, still wear Stetsons.

They were the Huey helicopters in Vietnam and the air cavalry. They became an armor tank division. You spoke a little bit about your time leading a tank organization and fielding the most advanced armor technology the world has ever seen. This was also the definition of the Powell doctrine that we talked about air-land combat here. Yet you go to Baghdad in 2004, where you can’t use tanks and heavy armor. It’s a sprawling city of eight million people. You have 20,000 soldiers under your command and are in urban combat.

Yet you weren’t allowed to bring your tanks. The Pentagon said, “No.” You understood it and didn’t necessarily agree with it. When you looked at having to prepare your organization for going into Baghdad, Iraq, the war has been going on a little bit under a year at this point. It’s so outside the realm of what the division had trained for. When do you think about your position there in that time as the leader of the organization, what went through your mind? Were you looking to say, “We quickly have to adapt and iterate on what we’re doing to give ourselves the best chance of being successful?

I owe that to listening to somebody, and the person I listened to was Marty Dempsey. I was going to assume responsibility for Baghdad when I moved in. He and the first Armor Division had it. I moved in and went on a two-week reconnaissance, and left seat ride with him 4 or 5 months before we deployed. He pointed to things like Sadr City and said, “We haven’t had a single incident down there, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen.”

He pointed to other areas in and around Baghdad that were tough, but he said, “What we’re going to need to get ready to do is there’s been a heck of a lot of money that has been given to us by Congress. It’s going to be used to try to rebuild the infrastructure here. You better get ready to execute some of those contracts.

If I were you, I’d go back and learn everything I could about the four things that seem to be the most important over here to the Iraqis. 1) Is electricity. 2) Is sewage. 3) Is potable water. 4) Is one that I’d never thought of, getting your garbage picked up. When you talk about a public health problem, have sewage and garbage issues.

These are all things we take for granted.

[bctt tweet=”PTS comes in different degrees.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Marty said, “Go back and learn and make sure your soldiers know everything they can about that.” How do you do that with the heaviest division in the United States Army? I talked to my leaders, and I said, “We got a big city near us, not as big as Baghdad, but probably has some of those same issues.” We went down, spent a week in Austin, and had support from the mayor. They talked us through all those essential services and what we needed to look for. They opened up a line that we could get on when we ran into issues and what we used to call video teleconferencing before Zoom with the folks at Austin.

The guy that impressed me was the garbage guy. He basically said, “Garbage is respect for the customer.” He expects you to come on whatever schedule you set. Once you set that schedule, you show up and pick up his garbage. It’s as simple as that, wherever it might be, and understand the culture. It’s probably different in Baghdad than it is in Austin. He was 100% right.

By the time I spent my time in Baghdad, I knew more about sewers and how sewers operated. I think that most engineers know about sewers and the different kinds of sewers that operate, but spending that time in Austin was absolutely fantastic. It opened my leader’s eyes up to that. At the same time, I realized the decision not to bring our armor over because it portrayed the wrong thing.

We were an invading force to me, was short-sided. Let me park it, but make sure that it’s available for me in the event that I need it. I will never forget the events of April 4th, when I was taking over that sector for Marty Dempsey. The one question that I was asked in my two years in Iraq, that I couldn’t answer, was a young E6 after we lost 8 and had over 60 individuals wounded in about a four-hour period on April 4th of 2004, was a young E6 who said, “Sir, why didn’t we bring our tanks? Why didn’t we have our tanks?”

I could not answer that question. Leadership is about listening. I listened to Marty. Not only did he tell me about the need to understand basic services work, but at the same time, he told me, “This is a dangerous place, and because I haven’t had anything happen in Sadr City in a year that I’ve been over here doesn’t mean that you won’t, so be prepared for both.”

The other parallel track in the establishment of basic services, which led to job creation and improved quality of life for the Iraqis, was the counterinsurgency aspect of this, or the need that we, like the US, could not become this occupier. I was in a heavily mechanized infantry platoon in Fourth Infantry Division, and that was a struggle we faced every day. Do we take the Humvees? Do we take the Bradleys while we’re getting hit? If we don’t have the Bradleys, we’re exposed. We don’t have what we need to protect ourselves and fire back.

If we bring the Bradleys into the city, now they see us as the occupying force. At the end of the day, in counterinsurgency, such a big part of it is training the host nation, training the locals to be able to assume their own responsibility, within the government, the political aspects, basic services, and protection, internal police and then also with the defense and their military.

When you went there, one of your big charges was how do you empower now the Iraqi government, military police to be able to start to solve their own problems? How do they come together as Iraqis? When we went to Iraq, we could argue, was there a sense of nationalism under Saddam? Was it forced nationalism? Will we ever know? I don’t know, but what we do know is that our entrance into there did create a Sunni-Shia divide and led to some ethnic tensions.

It didn’t help possibly that we entered into de-Baathification, which then disbanded all these essential services. We didn’t allow those people to take control and be in charge. When you think about, “You’re here. You have to get these people to come back together. You have to get your team to work with them.” The only way you’re going to do this is through teamwork and unity of effort without being seen as this occupier. How do you think through that complexity?

It’s all about team building and listening to your folks. Going back to some of those lessons you learned growing up, I always tell young leaders to remember the things that upset you. I remember an Army three-star general growing up, never understood why you had to go ahead and clean your quarters. Having an inspection by a bureaucrat that came over with the white gloves and the whole nine yards failed you the first time and made you and your wife do it again, or hire an outside cleaning team to come and do it. You’d finally get the paperwork signed off on and roll out of your driveway as a truck was coming in to go ahead and paint your place.

Why did you go through all that cleaning if you’re going to have a whole bunch of painters working for minimum wage come in and paint that same place? He changed that when he got himself into a position where he could change that. That’s one of the things that I remembered from my youth as an Armor Calvary company commander, who was always chopped to a different unit. It was absolutely critical that you had a feeling of belonging to that particular unit.

When it came time to train the Iraqi soldiers, I drew back on that lesson learned. I said, “Rather than set up individual units that go around and train the Iraqi military and work in the operational area of one of my brigades, creating all the friction that creates, I’m going to make that a brigade responsibility to apply the resources it needs to train the Iraqis within their operational area. It should take away some of that friction and make the traders feel that they are part of the unit.”

We got that right in the First Cavalry Division. I think subsequently, with the creation of outside teams that came in, rather than making it an operational requirement, to train the Iraqis within your particular sector was a lesson that we should have learned and worked on. Instead, we applied a different model that I think created some of the issues we have.

You’re an optimist like me. I read about you and did the research. I read The Fourth Star book that highlights you, General Petraeus, General Casey, and General Abizaid. I think so much along the same lines that you do. You believe people are good, and inherently want to do the right thing. If you give them the right tools that they’re going to drive themselves to be successful, they’re going to do it at all costs. They’re not going to let you down, but I feel like that mindset builds great teams and great organizations, but we’re also prone to be disappointed when we look at others.

We say, “I expected so much and you to do this.” When you were looking back on Iraq and as you transitioned into the vice chief role. We’ve got into 2008, 2009. We started having this feeling about did we want this more than the Iraqis wanted it? Were we more committed than they were? How do you continue to motivate the force?

I asked you this question because, in a lot of ways where we sit now, we’re at the end of the global war on terror. Officially it’s over. We’re moving on to the next thing. We have to reconcile where we were and what we did for many years. You lost 168 soldiers as the division commander during a difficult time in Iraq. When you look back on that, you think about where we go from here? How do you sum up the years of the global war on terror?

It wasn’t a whole of government effort. That’s how I sum it up. If you leave it up to me, the problem with us and guys like me is if you give me a mission, I’m going to do everything I possibly can to get it done. If you don’t give me all the resources I need, I’m going to look elsewhere to find those resources or figure out a way to do the job without having them. If you go back and I’m a student of History, I know it’s hard to make comparisons between what happened in Iraq and Afghanistan and World War II.

In World War II, it was a whole of government effort. It was everybody contributed. Quite frankly, that’s not what we have seen over many years. We in the military have a belief that we can solve any problem. The fact of the matter is I think you get what you get when you leave it up to us without bringing the whole government to bear and all the power of government. That power not only resides in its military, but it also resides in a whole bunch of other things.

I remember they’ve been fighting and doing so many things in Iraq for so long that their farmers had forgotten how to farm in the areas they were. Early on in my first tour as division commander, I remember asking to get some agronomists over from universities, and they were more than willing to come. They went into these very difficult places all the time as what they were doing as university agronomists and helping people in very dangerous places. They were willing to come, but I couldn’t get clearance from the United States government to bring these folks in.

It could have been tremendously helpful for many of these colleges to provide the Iraqi with something that they needed. I think that’s one example of a whole bunch that I could give you that shows that we did not fight these wars with a whole government approach. Had we done that? I think you would have seen a totally different outcome.

I can train anybody to fight, but if there’s not a government behind them that is going to do the kinds of things that our government does for our service and women, they are not going to be the effective fighting force that we are. That is so important to understand. This may sound self-serving because I’m a military guy. I did a great job training armies in both countries. What we did was a poor job of creating governments who could support those armies when it came time for us to leave. That, to me, is a failure. Had we done that, brought a whole of government approach to that, I think we would have had a totally different outcome than we did in probably a much shorter period than the many years it took us to reach the positions that we did.

We saw that at the exit of Afghanistan. A lot of people are asking, “How did many years go away in six days?” It came down to the logistics that we pulled, and we had not invested enough in their ability to maintain the logistics. Certainly, there are a lot of other factors, and there was a simplistic view of it. That precipitated an accelerated and is used as an example here to show that if we don’t invest in the totality of everything, simply training folks to fight can’t stand.

The other issue that I always talk to folks about is force caps. We ask a commander to tell you how many folks he will need to accomplish the mission that he’s asked. If it falls outside a number that we don’t want to support, we place a force cap on it. I can go time after time. I will never forget Bob Gates’s story when they were getting ready to go in the Gulf. Colin Powell was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Norman Schwarzkopf came to him after he had done his evaluation, where he was going to need to get the Iraqis out of Kuwait, and Norman came and said, “I’m going to need a Corps out of Europe.” Powell looked at me, and he said, “Are you sure?” He said, “I’m going to need a Corps out of Europe.” He said, “Are you ready to tell the president that and explain that to the president?” Schwarzkopf said, “I am.” They went to Kennebunkport, and Bob Gates said I’ll never forget. Norman Schwarzkopf came into the room. The president had asked him for his evaluation. He said, “I’m going to need all these forces out of Europe in order to do this.”

The president looked at him and said, “Are you sure that you’re going to need all those?” He said, “Yes, Mr. President, I’m sure.” President Bush said, “Approved,” and walked out of the room. We lost that in Iraq and Afghanistan. I don’t need to recount for you the number of times the decisions were made on force caps. I don’t think the American people understand that you had a force cap on uniform personnel, but you did not have force caps on contractors.

I remember that the statistic that still shocks me in Iraq is when I left Iraq for the first time in 2005. There were two contractors for every soldier that was stationed over there. I think there’s a lot of lessons learned that we can pull out of this whole thing. It comes down to if you want a bumper sticker to place on it, don’t enter into a conflict, a war if you don’t have a whole of government effort and are able and ready to apply all the powers, both kinetic and non-kinetic, that the government has in order to meet a well-defined objective.

[bctt tweet=”When we reach it together, we will solve the tough issues that we’re trying to solve.” username=”talentwargroup”]

You teed up my next quote perfectly, and it comes from The Fourth Star, and the author is David Cloud. Greg Jeff says, “Generals didn’t get to pick the wars they were asked to win. There was no guarantee that a future White House wouldn’t send the Army into another misbegotten conflict or that a crisis wouldn’t emerge requiring a large conventional ground force. As Iraq had shown, the Army had to be ready for a whole range of contingencies.

Chiarelli wasn’t sure he could predict what the next war would look like, but he knew what kind of officers would be needed. He wanted an officer corps that argued, debated, and took intellectual risks. As you look forward, we have this term hybrid warfare. What do you see the next battlefield looking like?

I see that quote as much more important now than when I uttered it. We need that same kind of leader. The leader is able to take intellectual risk, debate, and make sure that you’re applying what you’ve garnered over a career to whatever that problem is. We need lifelong learners who are able to understand. We need some other things. We need to reform our acquisition system. It doesn’t take the statement of a requirement to put something in the hands of the soldiers, 12 to 14 years to do that. There are other things that we need to do. We need to break some of the molds that have guided us in the past. More than anything, we need leaders exactly as I described in that quote. I believe that with all my heart because we can’t predict the future. We don’t know what’s going to happen.

As we close out, I ask every guest the three things they do every day to be successful. I quantify it in terms of the Jedburghs in World War II had to do three things as core foundational tasks. They had to be able to shoot, move and communicate. If they did these three things with the utmost proficiency every day, they could apply their focus to other challenges that came their way. What are the three things that you do every day to be successful?

First, I do what one of my heroes told a graduating class to do. The very first thing I do is make my bed. Bill McRaven said that in a very famous speech. That’s an important task if you do that every day. Granted, my wife is in bed a little longer than I am, and she makes it, but if I’m alone, I make my bed every day.

The second thing I try to do is put aside at least 60 minutes a day to read. I like to take myself outside of my comfort zone. I will read a medical paper on a particular protein associated with traumatic brain injury in individuals. I will read out of my comfort zone for a Liberal Arts guy in some things that engineers only do. I always try to put together 60 minutes to do that.

I can’t stop working, and I’ve got different teams doing different things. How can I make my team better? How can I create an environment that is going to allow them to reach their full potential? When we reach it together, we will solve the tough issues that we’re trying to solve. I stay engaged, keep my mind going, and build those teams in whatever I’m doing is absolutely critical to me. Those are the three things that occupy my day, every single day.

Make your bed, dedicate 60 minutes or some time to read outside of your comfort zone to develop yourself further and develop and invest in the team and find a way to drive them to their maximum potential. We talked about the nine characteristics of elite performance as defined by special operations. A driving force here, drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, curiosity, team ability, effective intelligence and emotional strength.

At the end of every episode, I take 1 or 2 of them, and sometimes I’ve taken all of them. I’ve applied them to my guests and what I think they characterize and show us every single day. Teamwork, I certainly believe, is one of your strongest since we’ve spoken a lot about it, but I also think curiosity is a big one. The challenge of the status quo, continuous learner, development of yourself, and those around you to find innovative ways to solve complex challenges, you’ve demonstrated this in your career from your first days as an ROTC cadet, all the way through the leader of the Army.

You’re one of the most successful leaders our military and our nation have ever seen. You’re an eternal optimist. You see the good in people, value their hard work, push them to be the best versions of themselves, and set the example for the rest of us to follow. I thank you so much for your service and for joining me. I look forward to continuing the conversation with you in the future as we continue to advocate for PTS, TBI, and all of the factors and things that affect veterans out there. Thank you so much for joining me.

Thank you. It’s been wonderful talking with you.

Peter Chiarelli, U.S. Army General (retired) spent nearly 40 years of his life serving others while in the U.S. Army. As commander of the Multi-National Corps-Iraq, he coordinated the actions of all four military services and was responsible for the day-to-day combat operations of more than 147,000 U.S. and Coalition troops. While serving as the 32nd Vice Chief of Staff in the Army from 2008 to 2012, Chiarelli was responsible for the day-to-day operations of the Army and its 1.1 million active and reserve soldiers. It was during this time that General Chiarelli led the Department of Defense efforts on post-traumatic stress (PTS), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and suicide prevention.

Peter Chiarelli, U.S. Army General (retired) spent nearly 40 years of his life serving others while in the U.S. Army. As commander of the Multi-National Corps-Iraq, he coordinated the actions of all four military services and was responsible for the day-to-day combat operations of more than 147,000 U.S. and Coalition troops. While serving as the 32nd Vice Chief of Staff in the Army from 2008 to 2012, Chiarelli was responsible for the day-to-day operations of the Army and its 1.1 million active and reserve soldiers. It was during this time that General Chiarelli led the Department of Defense efforts on post-traumatic stress (PTS), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and suicide prevention.

Immediately after retiring from the U.S. Army in early 2012, General Chiarelli became the first CEO of One Mind. Along with leading the organization’s strategic initiatives, he continued to advance his advocacy on brain health. He worked expeditiously with members in the government, corporate, scientific and philanthropic communities to greatly accelerate large-scale research for brain illnesses and injuries through Open Science data sharing and collaboration. His recent achievements include leading One Mind’s support of the TRACK-TBI research collaboration, aiding TRACK-TBI in its progress towards obtaining FDA approval of biologically-based biomarkers for TBI and building the foundation for the TRACK-TBI and AURORA ‘mega-collaboratory’ that will combine the data from these two large-scale longitudinal studies to determine the TBI and PTS comorbidity overlap.

Although General Chiarelli retired as the CEO from One Mind in early 2018, his passion and drive for the organization and for finding cures for neurodegenerative diseases remains explicit. While he looks forward to spending more time with his family, General Chiarelli still plans to continue his earnest efforts to aid One Mind in their neurodegenerative efforts as a One Mind Ambassador. We are thankful for his past, present and future support!