The Department of Veterans Affairs is one of the most complex organizations in government. At the center of this complexity is VA disability ratings and compensation; a program developed over 200 years ago to compensate service members while they recovered from service. Today, this program is convoluted, lengthy and often the most challenging process a Veteran must endure during transition to civilian life.

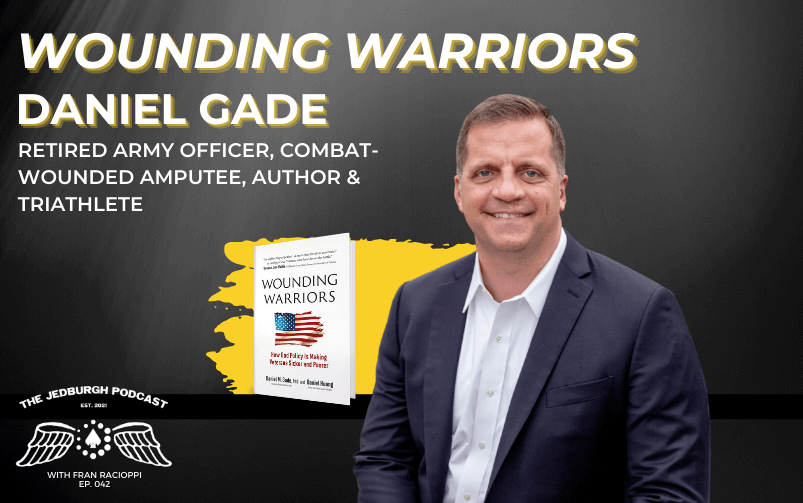

Daniel Gade, a retired Army Officer, combat-wounded amputee and author of Wounding Warriors: How Bad Policy is Making Veterans Sicker and Poorer joins host Fran Racioppi to challenge the current one-size fits all approach to VA disability compensation calling it outdated and antiquated; as well as providing recommendations for reform.

Daniel served in the Bush and Obama administrations and was the Republican nominee in the 2020 election to represent Virginia in the US Senate.

—

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

Daniel Gade was born and raised in Minot, North Dakota. He enlisted in the Army in 1992 and deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom as a company commander in August 2004. He was wounded by enemy fire twice and decorated for valor; the second wounding resulted in the amputation of his entire right leg. After retiring from the Army as a Lieutenant Colonel in 2017, he accepted a political appointment as a Senior Advisor at the US Department of Labor’s Veterans Employment and Training Service (VETS). In 2019, he ran unsuccessfully for United States Senate in Virginia, but garnered more votes than any Republican candidate in Virginia history.

Daniel Gade was born and raised in Minot, North Dakota. He enlisted in the Army in 1992 and deployed to Operation Iraqi Freedom as a company commander in August 2004. He was wounded by enemy fire twice and decorated for valor; the second wounding resulted in the amputation of his entire right leg. After retiring from the Army as a Lieutenant Colonel in 2017, he accepted a political appointment as a Senior Advisor at the US Department of Labor’s Veterans Employment and Training Service (VETS). In 2019, he ran unsuccessfully for United States Senate in Virginia, but garnered more votes than any Republican candidate in Virginia history.

Daniel’s military awards and decorations include the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, two Purple Hearts, the Combat Action Badge, Ranger Tab, Presidential Service Badge, and both Airborne and Air Assault wings. He and his family reside in Mount Vernon, Virginia.

The Department of Veterans Administration has one of the most important missions in government, to support the reintegration and rehabilitation of our nation’s veterans. The VA provides health care, education, and training to assist those who served in developing the skills needed to find success in their post-military careers.

The VA is also one of the most complex organizations in government. At the center of this complexity is VA Disability Ratings and Compensation, a program developed over 200 years ago to compensate soldiers while they recovered from service. This program is convoluted, lengthy, and often the most challenging process a veteran must endure during the transition to civilian life.

I’m joined in this episode by Dan Gade, a retired Army officer and author of the book Wounding Warriors: How Bad Policy Is Making Veterans Sicker and Poorer. Dan became an amputee in 2005 while serving as a company commander in Iraq. He later served as a professor at West Point. He held positions in both the Bush and Obama administrations and served as a Senior Advisor to the Secretary of Labor in the Veterans Employment and Training service. Dan was the Republican nominee in the 2020 election to represent Virginia in the United States Senate.

Dan and I discuss his somewhat controversial book where he challenges the VA Disability Compensation program, calling it outdated and antiquated. We break down the claims process, the evaluation criteria, and the intended benefits of the programs. Dan shows us how the one size fits all approach to injury assessment is costing taxpayers billions, how many veterans are manipulating the system, and the effect it’s having on deserving veterans. Also, what we need to do to reform the system into a streamlined approach that’s fair to the taxpayer, the veteran, and society.

—

Dan, welcome to the show.

It’s a thrill to be on with you, Fran. Thanks so much.

We’ve hosted several episodes on the military, mental health, supporting veterans, even on national security. We’ve told the stories through the lens of human performance, improving physical, mental, and emotional capability and capacity. We’ve remained patriots in our conversations but at times, we have questioned policy and decision-making. We’ve forced our readers, our guests, even myself to think about decisions that we’ve made as a country, as leaders. Whether that be in the military, as entrepreneurs, business people, athletes, can we force ourselves to think about how we do things and maybe find a better way?

I said going into 2022 that we were going to ramp it up. We are going to challenge the status quo. We are going to ask harder questions. We’re going to have more difficult conversations. This conversation, your book, Wounding Warriors: How Bad Policy Is Making Veterans Sicker and Poorer, kicks off this 2022 with a full marine-style frontal assault. I throw that out for our brothers in the Marines. I appreciate you taking the time to join me. I’ve been looking forward to this conversation. I finished the book and I’ve got many different questions to ask you.

It’s great to be with you. To the Marines who are reading, I would say that they are my brothers because they saved my life in combat. I have a fondness for the Marine Corps as every red-blooded American should.

As we must, you pulled no punches in Wounding Warriors. You go right at the VA and right at their policies that guide the organization. The tone of the book gets set right up front with a quote that pretty well summarizes your position, “The VA operates like a misguided assembly line, churning out the diagnosis of disability and applying bandages of cash in lieu of the rehabilitative care veterans deserve.” The transition from the military is one of the hardest, if not the hardest challenge that a veteran has to face.

The VA is supposed to make it easier. We can argue all day long that probably rarely that’s the case but navigating the VA has become almost a common bond between veterans. They tell stories about it. Your argument aims at the core definitions of disability and service-related injuries and also the process by which a veteran has to go about to receive their awarded benefits. You call the process outdated and antiquated. At the most foundational level, what is the VA disability model? What’s it based on? Why is compensation at the center of that discussion?

[bctt tweet=”We need a holistic review of the veteran life course. ” username=”talentwargroup”]

Do you know how if you spent any time around the ocean and you know something about coral reefs? One way to think about policy is to think about it as a series of coral reefs or a series of individual corals. The corals get together and they make a reef eventually and then their skeletons are these big complex things. The Great Barrier Reef in Australia didn’t grow up all of a sudden. It grew up little by little. That’s how policy works too. The book, Wounding Warriors, is available at WoundingWarriors.com. You can read reviews. You can read a couple of chapters there and get a flavor for the direction the book takes.

What we described is a system that came up little by little and nobody ever stepped back and said, “We’re going to take a holistic review of the veteran lifecycle from the day somebody lists or is commissioned all the way through when they’re buried in a veterans cemetery.” We never looked at that entire life course and said, “What are the turning points? What are the key nodes where people need help? How can we serve them throughout their life course?”

Instead, little by little, the policy was developed that resulted in the system we see now. Here are some features of the system we see now. I’ll personalize this for you, Fran. You could probably tell the same stories. I’d love to hear your stories on this too. When I was getting ready to retire from the Army at age 42, I went in for my VA appointments because you got to go to improve VA appointments.

Forty of them too. It’s not two.

I was going into this appointment. I’m a hip-level amputee. I was blown up badly in Iraq. I’ve got all these issues. All of them are combat-related. I go in and the guy says, “What do you want to claim on your VA disability form?” I said, “I’m a hip-level amputee. I’ll claim that. I’ve got this pretty significant scar on my face. I’ll claim that. My whole abdomen looks like somebody lit it on fire and put it out with an ice pick because of surgeries and stuff. I’ll claim that. I’m missing some parts here and there and I’ll claim that stuff.”

He’s like, “All that is documented in your record. That sounds fine. What about your brain injury?” I go, “I don’t have a brain injury. What are you talking about?” He goes, “I can get you paid for a brain injury. All I want you to do is put down a brain injury on the sheet.” I’m like, “I don’t have a brain injury.” He goes, “You’ve got blown up. You were unconscious for a while. You have a brain injury. Write it down.” I’m like, “No. Since I got blown up, I’ve gotten a Master’s degree and a PhD. I’ve taught at West Point. I’ve worked at the White House on veterans’ policy. I’m fine. I don’t have a brain injury. Maybe down the road, I’ll have some CTE or something like that. Right now, I’m fine.”

He goes, “You’re not understanding. Put it down and I can get you money for it.” I said, “You’re not understanding. I’m not going to claim a brain injury.” He’s like, “Fine. You know what you’re doing. What about your hearing loss?” I go, “I don’t have hearing loss.” We went through the same conversation. He goes, “You were a tanker.” “Yes, I was a tanker. We shoot big machine guns and all this stuff.” He’s like, “You were around a lot of loud stuff a lot.” “Including the explosion that was 3 feet away from where I lost my leg. I had earplugs in when that happened.” At age 42, my hearing was the same as when I was commissioned in the Army at 21 or 22. I have the test and it shows.

I go, “I don’t have hearing loss.” He goes, “You can claim it and it’ll get you paid.” I’m like, “Wait a second.” I knew that the system was driving veterans to see themselves as sick. I never saw it on my own terms. That’s what we have right now. We have a system that drives veterans into this benevolent, soft, kind, engaging, “Here’s some money for every little thing that’s wrong with you,” way. The problem with that is it’s fundamentally identity-distorting for veterans. It causes veterans to see themselves not just to be paid to be sick but to see themselves as sick or as disabled or as useless and worthless.

The book is not some hardcore policy book. It’s also that and it’s well documented but it’s a series of stories about individual people and their experiences. They’re all nicely woven together. A woman in the book describes herself how she feels about herself after going through that process. She says, “I feel like a discarded government waste.” Too many veterans feel that way. What we’re going at here is not the VA. We’re not going at veterans. We’re not trying to tear down systems.

What we are trying to do is reimagine how we can create a system that helps veterans thrive instead of helping veterans not thrive. Anybody out there who says, “Veterans are thriving right now,” that’s true. Veterans have good employment stats. In part, veterans are doing fine. The suicide rate is not steady, not declining, it’s climbing rapidly among veterans. Anybody who says veterans are doing fine simply isn’t paying attention. I argue that what we can do to help them be better is what we should be doing to help them be better.

Let’s talk about some of the numbers behind this. You said it here but you also said on paper, “Veterans are sicker now than they’ve ever been. The cost of veteran care and disability compensation is also the highest that it’s ever been for the organization as a whole.” There are some numbers from the book. During the Global War on Terror from 2001 to 2020, vets receiving disability benefits are up to 2X but the vet population has fallen by 1/3. 36% of post 9/11 veterans receive disability compensation versus 11% in World War II.

The average vet receives compensation for 7.9 conditions as opposed to World Wars II’s 2.4 conditions. Since 2000, the number of vets rated 70% to 100%, the maximum at the scale, has increased seven times. We can contrast that to the actual number of injuries and lives lost in these conflicts. The Global War on Terror is under 7,000. Vietnam, over 58,000. Korea, over 36,000. World War II, over 405,000. Why are the numbers for disability so much higher now than they are in past conflicts, especially in terms of the fact that there are so many advancements in medicine?

Wounding Warriors: How Bad Policy Is Making Veterans Sicker and Poorer

You’ll hear or read a common thing out there. Whenever anybody talks about post 9/11 veterans, they say, “The reason why there are so many disabled veterans is it’s because of improved body armor.” If I hear the word improved body armor one more time, I’m going to fall out of my chair and kick and scream on the floor. They’ll say, “Improved body armor caused all these people to survive wounds that they would never have survived before.” Let me offer you a different view. In 2021, 250,000 veterans began receiving disability compensation. They received disability compensation for the first time.

In the twenty years of the war on terror, from 2001 to 2021, there were a total of around 55,000 wounded in action in any way. That’s 55,000 Purple Hearts. There were five times more people who began to receive disability compensation in 2021 than the total number of wounded in action in twenty years of armed conflict in Iraq and Afghanistan principally and in several other secondary and tertiary theaters. What we’re talking about here is a system that is way bigger than combat injuries.

You asked me why the system has grown so big or why the numbers are so big. Part of it is when every congressman and every congresswoman come in, they want to be like, “What can we do to build our coalitions, build our teams, have some legislation that everybody can get behind?” It’s like, “I know what’s popular, veterans are popular. What I’m going to do is write a bill that expands veteran’s benefits.”

Every year, when people come in, they try to expand veterans’ benefits. They expand here and there. They expand the definitions here and they say, “Bluewater Navy needs disability benefits. These people need benefits. If an old man gets diabetes, it might be because of his age and origin. He needs benefits. This guy got a concussion in training, so he probably needs disability benefits too.” They expand these definitions broadly.

At the same time, society other than veterans has become much more normalized with the idea of receiving benefits from the government. Receiving benefits from the government has become much more normalized across society. Veterans themselves, the door has been opened where anything that can be claimed will be claimed because there are all these people like the guy that I described encouraging veterans to do it. It’s a two-fold thing. For sure, way more people are claiming disability benefits than ever before. It’s distorting their identities. It’s causing real problems. We ought to take those problems directly to task whenever we see them.

When we make that distinction between combat-wounded versus non-combat wounded and we think about that in terms of what the VA is assessing, the VA is assessing both. Can you speak in a little bit more detail about why we have to make that differentiation between combat wounded and non-combat wounded? How does that come into the decision-making that the VA looks at?

It’s not very much. The answer is there’s no moral difference between somebody who got shot in combat as he was getting off of a truck and somebody who jumped off a truck in training and was badly injured in some accident related to that. Training accidents and combat injuries are morally equivalent. There are a couple of niche ways that retirement pay is treated, combat-related special compensation, and so forth that are specific to combat-injured people. There are some programs that are related specifically to Purple Heart recipients. That means somebody who was wounded in combat by enemy fire.

There are a few programs that are related only to combat but the bulk of VA disability compensation is related to things other than combat. There’s no distinction in the disability system between combat and non-combat, and I don’t think there should be. We ought to be much more careful about using the word disability when that’s not what we mean. The system uses the word disability in a flagrant way. The system uses the word broadly to describe anything wrong with a veteran.

The most common disability in the VA system is this hearing condition called tinnitus, which is ringing in the ears. If you’ve been on Facebook or anything like that, there are always these tinnitus ads. Maybe I get them but everybody does. The idea is that when it’s quiet, there are some people who’ll hear a ringing, a buzzing, or a popping sound in their ears. It’s normal. It’s common in the life course. There are lots of people who have it. It’s the number one “disability” in the VA system. There’s no test for it.

When the veteran comes in, the claims person will say, “Do you have tinnitus?” You say, “Yeah. My hearing bothers me terribly. Whenever I go to sleep, I hear this horrible hissing sound.” They check it off. If you’ve ever been to an audiologist in the military and you tell them you got it, they’re going to mark it down on your sheet. When the VA rates it, they’re going to give you 10%. They’re going to give you a little money for it. Is it a disability if half of Americans have it?

Another example and a real boogeyman in the system and a pretty disgusting problem, to be honest with you, is something called sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is characterized by choking and ceasing breathing while you’re sleeping. It’s a huge problem. It’s not snoring. It’s a serious problem. It can cause heart disease and all this stuff. It’s related to all kinds of bad conditions.

[bctt tweet=”We need to help veterans thrive and be better rather than paying them to be sick. ” username=”talentwargroup”]

Here’s the problem, the primary cause of sleep apnea is, number one, being male. Number two, having a narrow neck circumference. Number three, being overweight. If the VA rates you for sleep apnea and you use a positive pressure breathing machine, which alleviates the symptoms of sleep apnea and gets rid of all the problems, it’s perfect. They’re not fun. I don’t have one but I know people who have them and they take some getting used to.

They look uncomfortable.

It’s a 50% disability. A below-knee amputation is a 40% disability. An above-knee amputation is only 60% disability. Complete loss of an eye is only a 30% disability. About 25% of Americans have sleep apnea. According to the American Sleep Association, it’s the fastest-growing condition in all of American society. We’re supposed to pretend like it’s a 50% disabling condition, I don’t think so. The reality is vastly different.

We use the word disability far too broadly when we could have a system that’s rational and just that treats veterans for things like tinnitus and sleep apnea but doesn’t pay them or label them disabled. That labeling causes people to view themselves in a negative way and that can be destructive as well. We talk about that a good bit in the book too.

The cost behind this thing is incredible too. In this same period, the disability compensation in the $1 standpoint has tripled. The 2021 projections were for over $133 billion in benefits to 5.7 million beneficiaries. This is in addition to programs for education and health care but this number is greater than all of those other programs combined.

The quote you have in the book is that the VA spends more on veterans staying sick than on veterans getting better. How does this investment in the VA Disability Compensation affect other programs like the GI Bill, vocational rehab, or education programs? Money is a finite resource. If it has to be diverted to the compensation, what programs are we not able to provide because of the allocation of those funds?

I want to be careful here. I’m not somebody who says that we should take an ax to the VA’s budget. It’s roughly $240 billion. We shouldn’t necessarily take an ax to the VA’s budget. What we can do under a rational, cost-neutral proposal is if we were to take some of those dollars that are spent on disabilities that aren’t disabilities or on things that are not justly and rationally achieved. Put that money over into reemployment and over into entrepreneurship and over into those other programs.

We could reallocate things in a healthy way and help veterans thrive instead of doing it the way we do, which prioritizes disability and disability compensation over all those other programs. It’s an issue of priorities. If you follow the money, the VA’s priority is on paying people disability benefits and not on rehabilitating them, educating them, housing them, or helping them thrive and otherwise.

Those programs are impactful. When I got out, I went to NYU and I got my MBA. The GI Bill paid for the first year and vocational rehab paid for the second year. It was a tremendous experience that was provided by the VA. Speaking about the process, my process, which is still ongoing in my discussions with the VA for my disability rating, I was through my MBA program, which they funded before my word was generated on disability compensation.

There’s a long tail on a lot of disability claims. I’m not saying that veterans shouldn’t apply for disability. I’m saying that we ought to reform and restructure the system. Let’s lift the roof on those people with truly disabling conditions. You and I both know people who have serious and traumatic brain injuries, the kind where their skulls were open and where they have permanent functional problems or are wheelchair users forever or disabled in some other way, multiple amputees and things like that.

If we reprioritize the system to take care of those people with catastrophic disabilities and the rest of the people we’re prioritizing health care, education, entrepreneurship, and all these other things, then we can rationally do all of that. Helping veterans thrive and be better rather than paying them to be sick as the model.

Let’s talk about you. You entered the Army. You were seventeen years old. You went to West Point. You come from a family history of service. Your uncles served. Your mother was a huge patriot and instilled that in you and your family growing up. Why decide to even come into the Army in the first place and attend West Point?

There are a couple of things. My middle name is MacArthur.

After the general.

That should give you an indication of the family history here. I don’t know if you have any background in the military other than your own service course. The military is very much a family business. 30% of Marines have some family legacy in the Marines and the other services are less. For me, my father had fought in Vietnam as an infantryman. He was a college graduate. He was teaching in an elementary school or some high school or something when he got drafted. This is a 25-year-old draftee, not the eighteen-year-old that you hear about. There’s a 25-year-old draftee with a college degree. He went to Vietnam and fought.

I had a great uncle killed in the Philippines during World War II. He was a soldier in the Army who was part of the liberation of the Philippines. He was killed in February of 1945 on Luzon. It’s a long family history, a bunch of uncles, cousins, my older brother, and all these people who’ve gone to West Point. A long family history of the military and a reasonably long family history of West Point.

I decided to join in when I was seventeen because I love America. I had always been trained by my family and by my value set that I was going to be a person of service. I’m pro-military service. The Army is great. I love the Army. Anytime somebody can have an opportunity to serve others, they should do so. If my sons and my daughter don’t decide to go to the military, that’s 100% fine with me. I would suggest that they find some other way to serve others, at least for a while.

Before you go out and make a gazillion dollars in business, maybe find a way to teach in America or something and serve others in that way. The service was valuable to me. I enlisted in the Army as a private when I was seventeen plus three months. I was young. A year later, after basic training and everything, I found out that I’d gotten accepted at West Point. I went off to West Point and I graduated from there in ‘97 when I was 21 or 22.

You eventually became a company commander in Iraq in 2004 and 2005. You go to Ramadi, one of the most difficult areas. I was there in the latter part of 2005 and 2006. I will attest to the difficulty of that area but also the whole country during that time. You were wounded twice. One time, three months in. The second time, more catastrophically, was two months after that. Can you talk about those events and what happened in the injuries that you sustained?

When you were in Ramadi, were you straight infantry, or were you already Special Forces?

I was in Iraq. I wasn’t in Ramadi. I was in infantry at that point. I was in the city of Balad.

Ramadi was a terrible place. I was going to compare some place names with you.

I was in the 4th ID.

[bctt tweet=”We need to say the names of our fallen soldiers. ” username=”talentwargroup”]

I had been in the 2nd Infantry Division in Korea. I got to Korea in December of ‘01 after Ranger School as a captain. I was in Korea and took command of the tank company in Korea. I thought I’d missed the war. I was pretty mad about it. I thought, “Here I am as an armor officer but I’m stuck in Korea when there’s actual fighting going on in Iraq.” I was only a few days short of my change of command ceremony, leaving command to go on to other assignments, when my boss and his boss said, “We’re sending your soldiers. Do you want to go?” I said, “I do.” They sent me.

In the summer of ‘04, I got to Kuwait. In the early fall, September of ‘05, I got into Ramadi. It was a terrible place. You can look across the city and see burned-out buildings, burned-out cars, and scurrying people. There were enemies everywhere. We were constantly under small arms, RPG, rocket, IED fire constantly.

The first time I was wounded was November 10th, ‘04. I was in this firefight. If you remember November of ‘04, Phantom Fear is what it was called, The Take Back of Fallujah. Fallujah and Ramadi are two ends of a balloon. If you squeeze Fallujah, Ramadi gets bigger. All the smart, bad guys left Fallujah and came to Ramadi. All the dumb, bad guys stayed in Fallujah and died when the Marines and the Army took over Fallujah. That kicked off on November 7th, ‘04.

On November 10th, ‘04, I was leading this patrol across the city and we got in this firefight. We had engaged and destroyed a couple of enemy fighters on the ground at night with our tank, machine gun fire, not main gunfire. Our tank was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade that came off the roof of this mosque on the east side of Ramadi. It killed the soldier next to me.

Fran, I want to take a moment here. It’s important that we say their names. The soldier that was killed right next to me is named Dennis Miller. He’s from La Salle, Michigan. He was the only son of his father, Dennis and Mrs. Kathleen Miller. He’s buried in Michigan. I went to visit him there in 2019. I got to see his grave and stand by it. He was killed instantly by this RPG. It struck him directly and killed him instantly. I was wounded mildly in this engagement. I was returned to duty. I was out for the rest of the night but I was back at work the next day.

Two months later, I was hit again. This time, I was in my Humvee and not a tank. I was hit by an IED that ripped a big, huge hole right through my right thigh. I was sitting in the front right seat of the Humvee and the explosion was below me. It ripped a big chunk out of my thigh. I woke up on my back in the ditch and my soldiers were treating me. By the grace of God, the company medic had chosen to come along that day.

I remember this conversation because he wouldn’t normally come out. His name is Kurt Krause. Sergeant Krause wouldn’t normally come out with us. He would normally stay where the rest of the company was. He comes up and he’s like, “Sir, what are you doing?” I’m like, “I’m headed on this patrol.” He goes, “Can I come with you?” I’m like, “Why?” He goes, “I feel like I should be there.” I’m like, “Alright. Throw your stuff in the truck. Let’s go.” He goes, “Okay.”

He throws his kit of stuff in one of the other trucks. He was a senior company medic. He was on the scene moments after the Humvee rolled to the stop. He was there right away and was able to get the bleeding stuff. The other person who was on that mission who didn’t have any business being on the mission was my battalion executive officer. His name was Major Reggie Cotton. He retired as a colonel a couple of years ago.

Reggie was able to run up to me and was holding my hand and talking to me, trying to keep me out of shock and so forth. My Humvee’s radios had been destroyed or damaged in the blast. He was able to use his radio to call the brigade and get an air medevac back. Instead of waiting an hour, by which point I would have been dead for a ground medevac, he was able to get an air medevac there quickly. By the time I got to surgery, it was 37 minutes after the explosion. If you or I got hurt in our living rooms right now or our offices, it would take far longer than 30 minutes to get to a hospital.

I was in a surgeon’s care for 37 minutes. When I got there, my blood pressure was 60/0, which means I was moments from cardiac arrest and death. The guys did a bang-up job getting me off the battlefield. My last memory from Iraq is as the helicopter lifted off, I was still conscious. I was on a stretcher and I was in and out but I was conscious. I remember as the helicopter lifted off, I remember thinking, “Thank God, I’m saved.” I was far from safe at that point but they did a great job and they were able to stabilize me enough to get me back to the States. Monday, January 10th, ‘05 is when I got blown up. By Thursday, it would have been the 13th, I was back at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in the hands of a truly skilled team of clinicians.

You go through eleven months of rehabilitation and upwards of 40 surgeries. You said that your rehabilitation was relatively quick. Eleven months is a long time but for the injuries you sustained, it’s quick. You said that you weren’t going to sit around and wait for someone else to make you better. You were going to do it for yourself. That comment from you resonated with me because so much of what we try to instill in our readers and the stories we tell is that, in many ways, you control your destiny.

Things happen to you. Life happens. Events happen. How well do you execute on the soft characteristics we talked about, resiliency, adaptability, to some extent, even curiosity? How can I get out of this? How do I tie in my drive, the drive to take matters into my hand and do it? Can you talk a little bit more about that? When you were going through this rehabilitation, what was your mindset? It’s important to tie in here that you recovered and you have since become a triathlete. You’ve competed. You’ve won a triathlon. This is truly incredible.

My philosophy has always been to find a solution and engage with whatever the solution might be. My mom loves to tell this story. It’s a silly story. I finally became conscious again about three weeks after. They had me in this medically induced coma, a bunch of drugs on board, and all this stuff for a couple of weeks because there was no point in being conscious yet. I was in such dire straits that it’s better to leave me turned off and heavily sedated. The amputation itself occurred a week later after the explosion at Walter Reed.

When I first became conscious in the hospital, they told me, “You’re an amputee. You had a hip-level amputation on the right side.” One of my first questions was, “How high is the left leg?” I had these horrible dreams while I was unconscious about multiple amputations and about my genitals being destroyed and all this stuff. Thank God, none of that was true.

The truth was that my left leg was fine and my genitals were fine. I had to check on those items when I first became conscious. They said, “You’re a hip-level amputee.” One of the questions I asked was, “What is the optimal position of this hospital bed to promote healing? If I’ve got these controls, how high should I put the controls to put me in an optimal position for healing?” My mom was like, “Good. He’s going to be okay.” He’s asking questions like, “What is the optimal position for healing for an amputee?”

My philosophy was, “I’m done with the Army. Screw that.” I’m not done with being who I am. I’ve got to learn how to thrive again and get back on my foot. I’ve always been one of these people. I hate bumper stickers, generally. I like those ones that say, “Expect to self-rescue.” That philosophy is a good philosophy. The self-rescue philosophy is you are the master of your own ship. You are the one who’s responsible for whatever happens to you or doesn’t. That’s not fully true. If you approach life with that point of view, you’re going to end up overall in a healthier situation.

For me, I was like, “This happened. God’s got a plan for me. I firmly believe in God’s plan in my life.” What does that mean? I don’t get off the hook about being a husband and a father because I got mangled. I got to learn to live with being mangled. That’s the triathlon stuff you’re referring to. I was the world champion in the wheelchair one category of the Ironman 70.3 in Clearwater, Florida in November of 2010. A week later, I did the full Ironman Arizona with the same situation.

I still do CrossFit a good bit but I don’t do crazy and extreme stuff anymore. The extreme sports I was in for a while are almost like a coping mechanism in a sense. I was trying to convince myself in those years that I wasn’t disabled. If I can do an Ironman, I’m not disabled. It’s almost like extreme exercises as a form of self-medication. Maybe that wasn’t the best. This has taken years. It’s now 2022. Time heals a lot of things. For me to look back in that way is important. I did some cool stuff and had some great people alongside me to help me and make high expectations of me so that I would get back on my feet and learn to thrive again.

There’s another turning point in your rehabilitation that struck me and it’s important. Any parent, fathers especially, will resonate with it. Since I heard this story about you, it’s been a couple of days since I saw it and put this together. I sit and play with my son at night. Honestly, it keeps coming into my mind. There was an event that happened with your daughter. I won’t do it justice if I throw it out there. Can you talk about the interaction with your daughter that was a turning point?

When I was wounded, I had a hip level amputation and a crushed pelvis. I had some wounds in my left leg, which ended up healing fine over the years. At the time, it was still bandaged and stuff like that. I had nerve damage to both hands. I couldn’t move my hands. I couldn’t feel my fingers. I couldn’t lift my right wrist at all. I had a fractured skull and a broken neck. I had liver and kidney failure. I was in bad shape. Eventually, some of that stuff was resolved.

I got blown up in January ‘05. Around April ‘06, I was able to transfer from the hospital bed into a power wheelchair and get around the hospital and the hospital grounds in this wheelchair. I was still in it. I was in agony. It’s not a little pain but a lot of pain. I still had fentanyl pops and stuff like that. For those who don’t know what fentanyl pop is, I hope you never find out but they are awesome.

You don’t want one.

I’m in this power wheelchair and I’m in this living room of one of the Fisher Houses. By the way, one of the great success stories in veterans’ philanthropy is the Fisher House Foundation. If you don’t know about them, look them up. They’re awesome. I’m in the living room of this Fisher House and my daughter, who is 2 or 3 is sitting on the floor in front of me playing with these huge DUPLO LEGOs, the big and fat ones. She’s playing LEGOs by herself and sitting on the floor. My wife is in the other room making dinner for us. I’m in this wheelchair and I’m all padded. My pelvis is carefully padded.

[bctt tweet=”You are the master of your ship. You are the one who’s responsible for whatever happens to you. ” username=”talentwargroup”]

You had a broken pelvis.

She turns around and goes, “Daddy, will you play LEGOs with me?” I go, “I’m sorry, I can’t.” She goes, “Okay.” She turned around and looked at her Legos again. I hear her say under her breath, she goes, “My daddy can’t do anything.” Telling that story right now, Fran, I got chills running up my spine. I realized right then that I wanted to be the person who could do everything. I wanted to do everything.

I turned off the wheelchair and I carefully crawled out. I sat on the floor on this pillow to try to pad my pelvis and I played LEGOs with this kid. My wife came around the corner and saw me playing LEGOs and ran out, grabbed her camera, and came back and snapped the picture. It’s one of my favorite pictures. We’re playing LEGOs and she snapped a picture and that’s one of my favorite pictures. At that moment, I decided that I wasn’t going to become a victim of what had happened to me. I was going to self-rescue and I was going to be the man who did everything and that’s the man I strive to be.

You have gone on now and you continued your career in the military. You’re retired. You were a professor at West Point in the Department of Social Services. You served in the Bush and Obama administrations. I think about the experiences that you’ve had and you’ve listed a couple of times the injuries that you’ve had, the wounds that you have endured due to your service.

In the book, there’s a lot of conversation about these malingerers. You call them the malingerers. We call them malingerers. I was telling my daughter because she asked me what I was reading and I was telling her about it. I was explaining this piece about the malingerers. There’s a good portion of the book dedicated to the theory of Stolen Valor, which was also a book written by Jug Burkett and he referenced it heavily.

Can you talk a bit about this concept of Stolen Valor and how maybe the process that the VA is using has created this environment where people go and misrepresent themselves? They misrepresent their service. I look at that. I served and you served. I wasn’t injured in combat. I take offense when I see the stories of these people. I can only imagine what you go through and what you think about when you hear these stories. Can you talk a bit about this concept of Stolen Valor and why this has permeated today’s environment?

The reason we included the chapter Stolen Valor is that there are some parallels between what Jug Burkett talks about in that famous book and what we talked about with the disability system. Stolen Valor is about this Vietnam veteran who discovers that there’s a whole group, thousands of people who were Vietnam veterans. Maybe some of them weren’t even Vietnam veterans but represented themselves as Vietnam veterans for secondary gain, for fame, for glory, for free beer, to attract women. Whatever it was, they were doing this for a secondary gain.

We began to see parallels between that and the disability system, which has all kinds of secondary gain built into it if only you’re willing to do some little white lies or misrepresentation. For example, if you have a mental disorder, you have depression, or you have PTSD, real conditions that need treatment and that are serious and can be life-changing. If you say, “My condition has me laid out for two days a month,” you get X payment. If you go in and tell the clinician, “It has me laid out for ten days a month,” you get 3X compensation, for example.

There’s this whole system that says, “I’m going to misrepresent my disabilities. I’m going to misrepresent my conditions to receive more money for them.” We talked about this extensively throughout the book. There are veterans’ websites. There are Facebook groups. There are all these groups that are coaching people about explicitly how to do that and how to lie and misrepresent their disabilities to get higher compensation. There is a parallel there and it’s disturbing.

Do I believe most veterans are doing that? I do not. I believe that a lot of veterans are doing that. The evidence shows that a lot of veterans are doing that. To me, I would say that those folks are making a moral choice. I disagree with their morality on that and I wish they wouldn’t do it but there are some veterans who are doing that. They ought to take a good hard look at themselves.

When I’m signing books and sending them to people, I often use the phrase from John F. Kennedy’s only inaugural address when he says, “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” I say, “Ask not.” Honorable service doesn’t end when you hang up the uniform. The honorable service to your country includes the choices you make in with respect to disability benefits and with respect to how you want people to honor your service and all of that. There are some real heavy-duty choices that people should make and they should be thoughtful about how they make them.

The malingerer piece almost puts you in this circle. It’s this endless circle that has all these second and tertiary effects on the process. If you have people who are fabricating information, they’re embellishing information, what does the VA do in response? Now they have to create stricter criteria to evaluate it.

If there are stricter criteria to evaluate it, do you have a longer processing time? If there’s a longer processing time, do you have a potential where people who need benefits or would benefit from an expedited process because they can’t work? They are disabled to a point where the benefit is going to help them to achieve what they need to in daily life. That gets dragged out. This process of evaluation is extremely complex, the disability claim process. We joked about the 40 appointments. That’s not far off. The more things you claim, the more appointments you have, and the more convoluted the process becomes.

You referenced in the book that there are entire organizations that exist for the sole function of aiding a veteran through this application process, in this evaluation process. Can you speak a little bit about the evaluation process? What’s considered? What’s not? How is that then affected by this group of people who are stretching the truth?

The statutory obligation of the VA disability claims process is from the moment of service, when you begin service, there’s a presumption of soundness. In other words, you’re presumed to be 100%, physical and mental health status. Anything that happens to you during service, an injury or illness incurred during service or made worse by military service is considered to be service-connected. Notice that I didn’t say combat wounds. I said injury or illness.

If somebody comes into military service and they fall off a truck and shatter their hip, a serious injury that could result in a lifetime disability, that’s service-connected. Let’s say they get cancer while they’re in service or it’s one of the several kinds of cancers that could be related to toxic exposure or something, then the VA will say that’s service-connected. Let’s say they get cancer during the time when they’re wearing the uniform or they get something like Parkinson’s disease or they’re diagnosed with something like MS. Several of those are genetic type conditions that are considered to be service-connected because they occurred during service.

We’re not talking about people who lose limbs, lose eyes, spinal cord injuries, or anything like that. We’re talking about any change in your mental or physical health that occurs between the time you join and the time you leave. After you leave, any change that occurs could be related to one of the changes that occurred during service. Let’s say you end up with a hip injury on one side. Eventually, you’re overcompensating, so you end up with a sore hip on the other side. The second hip is also related to service because the first hip is what caused it.

You can claim that 5 years, 10 years down the road.

If that explanation seems complex, the reason is it’s a complex system. The claims manual for rating claims is thousands of pages. These poor guys and gals who are doing the claims process have to carefully trace the sequels, routes, this, that, and all the claims codes. They then come up with a unified disability level.

The whole system is built up like a coral reef over time and it’s irrational. If you were to design a system from scratch, you would never make it the way it is now. Instead, you would maybe say, “These things are disabilities. These things are truly disabling conditions. Over here are things that happen to people during service that we should treat them and we owe them some treatment and some rehabilitation for it but is it a disability? Do we want to be more careful about how we use that term?”

The reason the system takes so long, the reason people have long-term claim stuff, or the reason claims drag out over time is because of either 1 of 2 things is happening. One is they’re putting in claims that are difficult to substantiate. The time gap between when the thing happened and now or the medical evidence gap is weak. We have to find ways to fill in that evidence and it takes forever, or the person is putting in such a complex packet. They’re listing 100 things wrong with them.

There was one person that I know about who listed 128 conditions. It’s amazing to me. The poor claims processor person has to go through all of that and try to separate the wheat from the chaff. With 128 conditions, unless you’re in some hospital bed, there’s probably some chaff in there. They’ve got to separate the wheat from the chaff and that’s why the process takes so long.

If we were to redesign the system, a logical way to do it would be to take this basket of severe, no-kidding, life-altering stuff and say, “These are disabilities. You can claim this stuff. Over here, these are the conditions.” If you have the condition and a medical person checks it off, you need treatment for it. We should send you to the VA medical system, which is good. There’s nowhere in this book we critique the VA medical system because the VA medical system is excellent.

[bctt tweet=”Don’t become a victim of what happened to you.” username=”talentwargroup”]

A lot of people do. I live right by a military treatment facility. Because I’m a retiree, I’m allowed to use that. I go there. A lot of people go to the VA and love it. It varies a little by geography. There are some VAs that are better than others and stuff. The health care system is excellent. The disability system is the focus of the critique of the book.

You need a PhD in Mathematics to understand the calculations. Each claim that is made is rated to a certain percentage and then all of those are tabulated to then give you an overall percentage. Can you define permanent and total? This is another thing you said that affects veterans. It’s not only their physical capability, permanent and total, but their mindset.

I’d be happy to. A condition is called permanent when there’s no expectation of improvement. For example, I’m a hip-level amputee. I’m not a lizard and the year is not 2402. It’s 2022. There’s no rehabilitative medicine that’s going to make me grow back a leg. That’s a permanent injury. Total means, given that injury or illness, you are not expected to be able to sustain yourself but for disability benefits.

Here again, there’s a problem. The problem is there’s a lot of conditions for which people get permanent and total ratings where the condition is a solvable condition. The condition is one that treatment is available and efficacious. Veterans are afraid to go down that route because they’ll lose their disability benefits.

I’ll give you a true and perfect example, post-traumatic stress disorder. You and I both experienced combat. You, much more than me. Sadly, the enemy got luckier with me than you. We’ve experienced a lot of combat. We’ve seen dead people. We’ve seen dying people. We’ve seen friends die. We’ve seen the enemy die. I prefer to see the enemy die over friends dying. We’ve seen all this stuff.

Combat is traumatic. It sucks. It’s horrible and terrible. It’s also thrilling, wonderful, and lovely. PTSD is real. PTSD can be disabling. It’s also treatable. There are new treatments. There’s something called Stellate Ganglion Block, which is some injection in the neck that does this weird resetting of the neural pathways. Apparently, it’s good. I’ll introduce you to a guy. A friend of mine named James Lynch is a former SF doc who is doing something with that stuff. I don’t know that much about it.

He was the South African doc.

He delivered one of my twin sons. We were in school together at Belvoir. My wife was having our twins at Belvoir and he’s like, “Do you mind if I come over and scrub in?” I’m like, “Yeah, sure. Come on.” He came from the classroom with me. It was a C-section. The first doctor took the first baby out. The second one, Jim Lynch, took out my son and got him cleaned up and ready to take on the world.

He’s an awesome doc.

He’s a great guy. Stellate Ganglion Blocks are something called MDMA, street name ecstasy, which is a drug that was developed for some legit pharmaceutical use. There are some PTSD treatments that can be done with that.

People are using Ketamine.

Also, ayahuasca.

We’re going to do an episode about it.

There are some great people who’ve done stuff with Andy Stumpf on his podcast. We both know Andy. Reach out to some of those guys. There’s all this stuff. There are pharmaceutical treatments. There are also counseling therapies. There’s a lot of other things that can make people with PTSD get better. The problem is that military people with PTSD almost never get better.

The data is poor on their outcomes. The reason for that is, oftentimes, the veteran himself is looking at the $3,500 a month, he’s looking at the symptoms, and he’s saying, “I’m okay with having these symptoms as long as I get this payment. If these symptoms get better, I’m afraid to tell the doc.” When people hear that, there’s probably going to be some people who are pretty angry.

Talk to the physicians who are treating these people as I have. I did Grand Rounds at Walter Reed with the psychiatry department. Grand Rounds is a lecture series and the docs were like, “I got a lot in the North-South from the docs as I’m describing this problem.” Physicians are seeing this in their patients. Patients are afraid to get better because they lose their benefits. To me, PTSD is not permanent and total. It’s not something that requires permanent or total. It’s something treatable and a condition for which we can seek real improvement.

What about the veterans who have injuries that can’t be treated and the ones that the VA doesn’t have the capability to treat? How do you look at them? You described your personal situation. I’m asking the question more in terms of how the process has become convoluted that they have real problems that they can’t articulate or in enough detail describe. It’s now in a situation where they’re not getting what they may need. How do you cut through it? What do you do?

I’m a Republican. I’m not prone to giving praise to other administrations. The Obama administration started and then the Trump administration continued a series of bills. One is called the VA Choice Act. One is called the VA Mission Act. Those together built this infrastructure. The VA, whether they’re implementing them properly is an open question.

I don’t know the answer. I’m not throwing that rock. In theory, what that allows is people who can’t get the specialty care they need inside the VA or people who are getting routine care but can’t get in a timely way to get that care out on the economy as we would say on the military. As the rest of the world would say, in the normal healthcare system.

For somebody like you, you didn’t describe to me exactly what happened to you but your stroke inside of your eye is a niche thing. If you look at the veteran population and the age distribution, the VA is optimized for geriatric care. Is there a way to send you to Mayo Clinic or wherever the specialty eye doctors are that can figure that out? Yes. The VA should do that. They owe you that as a veteran. The system now allows for that to happen. I hope you’re getting the care you need.

There’s no reason to believe that because you’re a veteran, your conditions are veteran-specific. If you have an amputation, it doesn’t matter whether you got hit by a truck while you’re shoveling snow or whether your leg got blown off by an IED. An Amputation is an amputation and you go to the best amputee care place you can. Veterans should be able to do that. I’m all for veterans being able to seek care wherever they desire. Maybe somebody lives right next to the hospital and their wife and kids or their husband and kids if they’re a woman veteran. They go to that hospital. Why wouldn’t they go to that hospital too?

There are some real opportunities for serious reform if our political leadership at the presidential level will have the courage to do that reform. We need to help veterans thrive because what we’re doing is not working. We all know this. We need better community support. We need better governmental support. We need people who are willing to engage in this stuff in a serious way rather than send checks to veterans because they have tinnitus.

Let’s talk about where we go from here. Before we started, we were talking about it when you asked me what I thought about the book. I appreciated the honesty. Especially in the epilogue at the end, it speaks to what you said, “This is not a policy book. We’re not outlining hundreds or thousands of pages of line items that should occur. We don’t necessarily know exactly what right looks like but we know what wrong looks like. What’s happening right now is wrong.”

[bctt tweet=”Employment is powerfully protective and identity-shaping. ” username=”talentwargroup”]

You did identify three fairly concrete proposals or thought processes that we can go down to start these conversations. I want to get into them here. The first one is, “The goal of any system of veterans benefits in care should be to return the veteran as closely as possible to the life situation in which he would have found himself but for the service rendered. Our system must reject the idea that any veteran is unemployable or permanently and totally disabled.” We defined permanently and totally disabled. Why is it not a one size fits all approach? Why is employment the key factor that has to be put at the center for compensation?

Employment is powerfully protective and identity shaping in the lives of anybody, especially men. The research is unequivocal on this. On average, men derive their identities primarily from their work and women are able to drive their identities from work, family, and relationships. The last time you were on a plane, if you sat down next to somebody, the first question they asked you wasn’t, “What’s your name?” They said, “What do you do for a living? Where are you going? Are you going there for work?”

I haven’t talked to a single person on an airplane since COVID.

Masks are terrible and stupid and ridiculous. The people losing their minds and beating up flight attendants are evil and should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. The one good thing is that people are making less idle chit chat and bothering you less while you’re trying to listen to The Jedburgh Podcast. Part one is that work is identity forming. Part two is that work is also the basis of real financial and therefore, societal stability.

I’ll give you a straight-up mathematical thing. Let’s say a veteran gets $3,000 a month tax-free in disability payments. That’s door number one. We give that guy everything he wants on disability. We give him $3,000 a month, permanent and total, 100% disability, or $3,200 a month. That’s that or we give him a little bit more work to do by putting him through a rehabilitation program, an education program, and an entrepreneurship program. Now he’s earning $8,000 a month.

Which veteran is better off? Veteran B is because he gets the identity-shaping stuff of work and being able to say, “I’m a plumber.” If somebody says, “What do you do for a living?” “I’m a plumber. You got a problem and you think it’s gross, I can solve it and I can help you make your life better because I’m a plumber.” That’s powerful. That’s important stuff. By the way, he can make reasonable money doing that or even good money depending on if he’s a good plumber or if he owns his own business. He can make a lot of money.

I always talk about welders. A regular journeyman welder, a beginning welder, only a year out of trade school can earn $30 or $40 an hour easily. If he learns to do it underwater, he can earn ten times that. If he learns to do exotic metals underwater, he can earn 3 or 4 times that. Pretty soon, you’re talking about $1,000 an hour, which is real money if somebody is willing to do those high-risk projects. There are better ways to financial stability for veterans than forcing them into the disability system or enticing them into a system that on purpose or accident, separates them from the labor market.

The second one that you threw out here is, “The system should incentivize desired outcomes by linking treatment for an illness with the compensation associated with it.” It’s what I’ve called the no treatment, no benefits approach.

Earlier, I was talking about post-traumatic stress. There are a couple of other disorders like that, things like depression, things like maybe high blood pressure, even something extreme like cancer. Cancer is probably a poor example because anybody with cancer is pretty well motivated to get better. There are things that we compensate for that are amenable to treatment and with treatment, can be expected to improve. Mental health conditions are one of those.

If you go to VA health care appointments, if you go to community health care appointments, if you get treatment, you should expect that your depression or PTSD symptoms or whatever symptoms you’re having mental health-wise are going to get better. However, if you don’t go to treatment for those things, they’re not going to get better.

The treatment compensation link is something that psychiatrists had been bemoaning its absence for a long time. One thing we can do is if we link treatment compensation, it accomplishes three things. One is veterans who are better but don’t want the VA to know are going to not be motivated to go to those appointments. Maybe their payments will be cut off and that’s fine because their disability is gone. Two is people with serious disabilities that need treatment are going to get the treatment they need. You get the people in treatment who need to be in treatment.

Three is the hidden one and probably the most important. You and I both know people who are suffering in silence. Maybe they have PTSD but they don’t leave their house and they don’t go to treatment. They also don’t go to the grocery store. They also don’t engage with their family and friends. They are also living lives of reduced purpose, meaning, and value.

If those people don’t show up for their appointments, that should trigger an automatic thing where the VA is either calling or sending a social worker to that person’s house, knocking on the door, and saying, “Mrs. Veteran, are you okay? Mr. Veteran, are you okay?” Let’s proactively push health care and resources to those people who are probably the most suffering in society. It accomplishes three cool purposes.

I’ll give you a silly example. It’s not the year 2400. If my leg grew back, I’d be happy to walk myself over to the VA and say, “Time to stop the disability payments you’re giving me for my leg because my leg grew back and I’m fine.” We don’t do that same thing for other conditions and we should and that’s what the treatment compensation link would accomplish, among other things.

The third one is, “The system needs total reform in the nature and types of disabilities compensated and that there has to be a clear distinction between those injuries caused directly by military service and those incurred during military service.” You made that distinction. There are so many resources, time, money, and effort that go into some of these.

Evaluation, payments, and the debt goes into things that happened while you were in military service. The book even references someone who’s in a car accident and they were in a car accident and they found that you were compensated for the injury sustained in this car accident even though it was off duty. Can you talk a little bit more about that one?

For this one, I’m going to have to retreat to a moral question. For that, I’m going to use the example of eating meat. If you eat meat, you’re deciding that animal deserved to die so that you could eat it. Whether it’s something non-charismatic like a chicken or something charismatic like a bear, either way, you’re deciding that chicken, that bear, that deer, that cow, or whatever needs to die to feed you. That’s a moral decision. It’s not trivial. People should think about that. The same thing is true in this case.

I always talk about something I call the Ten Citizen Test. The Ten Citizen Test is as follows, what if you as a veteran walk up to ten random citizens and you say, “I’m a disabled veteran. My rating is X.” You say, “The conditions I’m being rated for are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.” Could you do that with a straight face? Follow up with that person and say, “That’s why your money is better in my pocket than in your pocket.” Could you do it? If you could, probably your things are legit. If the citizen says to you, “I’m a civilian truck driver. I have lower back pain, too. I have knee pain, too. I have diabetes, too. I have tinnitus, too. I have sleep apnea.” Back to that disaster of disability.

Fifty percent.

It’s insanity. If that person says, “I have sleep apnea too because it’s the fastest-growing condition in America.” Maybe you shouldn’t be claiming disability benefits for that thing. There’s a real opportunity here for people to realize that any dollar that’s generated by the civilian economy that’s taken by force by taxes and then redistributed to other people, there’s a moral component to that. As veterans, we should be used to dealing with moral stuff. We raised our right hand and swore an oath to support and defend the constitution. That’s a moral oath. We are willing to lay down our lives for our friends. That’s a moral oath. That’s a moral obligation.

We’ve got to be careful about making claims of our fellow citizens for things that are due to the fact that we live in a broken, fallen world. We have aging. We live with gravity. Your hips and the knees at age 46 don’t feel the same as they did at 26. They won’t feel the same at 66 as they do at 46. Is that because I was in the Army? I don’t think so. It’s because I live in a world with gravity. My mom was never in the army and her knees hurt sometimes. Is that a VA disability? Is that something that your fellow citizens should pay for? Is it because aging is hard? Aging sucks.

Sometimes we have bad luck. As a society, we have to deal with the consequences of bad luck all the time. Is bad luck the VAs responsibility? Is a veteran who had bad luck and got something happened to him related to that? Is that the moral responsibility of your next-door neighbor, who is not a veteran? I’m concerned.

The other one is a policy proposal. This one has only something that only veterans can do because veterans have to look at themselves and say, “Is it legit? Do I have sleep apnea because of something the government did to me? Do I sleep apnea because sleep apnea is a common condition related to obesity and maybe I should lose 50 pounds?” I don’t know. That’s a tough one.

That’s the moral question that everybody has to ask themselves. Only you can answer that. Reforming the VA is historically difficult. We see it all the time. It’s in the news and press right. Reforming the VA because of the bureaucracy is often extremely difficult to enact. You called it an iron triangle, an alliance between politicians, bureaucracy, and interest groups. Why is reform in the VA so hard? What are these three groups doing to keep the system in place and prevent monumental change if a monumental change is even needed?

[bctt tweet=”Let’s proactively push healthcare and resources to those who are most suffering in society.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Monumental change is needed. I hope that the arguments in Wounding Warriors will cause people to go buy a copy. Buy it on Amazon. I did the Audible audiobook myself, which is cool. You can listen to me read it to you. Listen to me on 1.4X because I had to read slowly. Because of the way the audio uploading is, I had to read ploddingly. Read the book and you’ll see that major reform is necessary.

The term iron triangle is a political science term that is well known in other contexts. The veterans iron triangle is the most difficult iron triangle in all of politics. In the ‘90s, welfare reform became a possibility. Left and right feel differently about welfare reform. I don’t want to get into the whole welfare reform thing here. The problem with veterans policy is that both left and right want veterans to get more stuff. The political left believes that all veterans are broken toys and victims of a patriarchal system that sends them to build empires overseas. Because they’re broken toys and victims, they deserve everything.

The political right says, “Anybody who ever even looked at a uniform, whether they’re a Medal of Honor recipient or a war criminal, is a hero and they deserve everything. As long as you ever looked at the uniform, you’re a hero. If you’re a generator mechanic who got other than honorable discharge because you wouldn’t show up at work on time sober, you served, you’re a hero.” They deserve everything. The political left and right agreed that veterans deserve everything. There are these powerful interest groups that stand under the deserve everything tree and shake it for money. Congress is only too happy to oblige by sending the money.

You get people who don’t know a thing about military service, John Stewart, for example. John is brilliant but he’s also empathetic, thoughtful, and cares deeply. He’s been bamboozled by the idea that veterans deserve everything. It’s a real problem. He doesn’t know why he believes that but that’s what he believes. That’s why the iron triangle exists. Veterans groups are only too happy to hide behind the shield of moral invincibility that having served gives them.

America is about 6% veterans. Our generation of guys and gals is about 1% or a little less than 1%. The 94% are terrified of criticizing veterans because they’ll be called unpatriotic or whatever. For me, I feel like any serious reform has to come from within veterans who listen to these arguments who are willing to lead and say to their fellow veterans, “Maybe you’re not disabled. Maybe what you need to do is get a job.” That’s a conversation that veterans should be having with each other.

What’s next for you? You ran for Senate in 2020. You were the Republican nominee. You went against Senator Mark Warner and the State of Virginia. There was a rumor that was out there for a second that you were going to run for governor, which would be pretty awesome. What’s next?

Fake rumor. I don’t know fully what’s next. I’m not wedded to politics. I don’t necessarily love politics or politicians. I do love the idea of serving. I’m happy to serve other people whenever I’m given an opportunity to do so. Honestly, the arguments and the case that we build in Wounding Warriors is a good one and an important one. I’m willing to devote my life to helping veterans thrive. I don’t want to be a professional veteran. Just because I lost a leg in combat, it doesn’t mean that I want to be a professional veteran. There are a lot of people out there who need better health care, better support, better services, and I’m happy to serve them.

There’s a great portion of the book too that brings in Dr. Chris Frueh. For those readers who have read a number of our episodes, Dr. Chris Frueh joined us. It was episode 18. We spoke about Operators Syndrome. He’s been an incredible force in veteran advocacy and has a long history of his work at the VA. Your portrayal of him in the book does a great job of outlining what’s going on, how it is perceived from the medical community, somebody within the medical community, also from the veterans. I truly commend the work that’s been done in writing this book. I enjoyed it.

As we close out, I ask all my guests, what are the three things that you do every day to be successful? It’s important here on the show because the Jedburghs in World War II had to do three things as their core foundational core tasks. They had to be able to shoot, move, and communicate. If they did these three things with precision every day, they could apply their focus and energy to other challenges that came about and they could solve them with success. What are the three things that you do every day in your world to be successful?

The first thing I do every day when I’m in the same house with them is to hug my kids. I’ve got three kids. I tell my boys, “The first task every day is to hug your dad. Come find me and hug me.” One day, it’ll be the last time. I’ll die or they’ll die. It’ll be the last time forever, one time. I would hate for that to be a day when I didn’t get hugged. That’s part one.

Part two is I try to do this. I don’t do it as faithfully as I should. I don’t want to get all woo-woo religious with you. Connect you to something greater than yourself. I should read my Bible every day. I should pray every day. That connects me to something greater than myself. That connects me to God’s will for my life, which is important.

Taking a moment to set aside and say, “I’m not the center. God is the center. I’m serving him.” That’s important. If you don’t believe that God exists or whatever, find something else that you believe is the center and serve that. Trust me, it’s not you. You’re not the center. I’m not saying that you’re not the center. None of us is the center. Something bigger than ourselves is the center. Finding a way to connect to that center is important.

[bctt tweet=”Find a way to serve others.” username=”talentwargroup”]

The third thing is to serve others. Find a way to serve others. Is it shoveling your neighbor’s walk? I only have one leg, so I’m not a good snow shoveler. We had a big, epic snowstorm. I have an ATV and a plow on the ATV. I went out and plowed a bunch of people’s driveways in my neighborhood. Why? It’s because I have an ATV with a plow. I can clear a driveway in five minutes. It would take a little lady with a shovel five days or never. Find a way to serve others inside of your capability. By serving others, you’re also making the world a better place. We all deserve to pass a better place onto our kids and our grandkids.

Hug your kids every day, connect with something greater than yourself, and serve others. I love all three of those. At the end of our show, I often talk about the nine characteristics of elite performance that are used by Special Operations Forces. We started talking more about attributes as well and what defines not only elite performance but optimal performance, human performance. There are so many we could throw out there. Rich Diviney talks about 25. There are 30 or 50 of them that you could say.

Many come to my mind when I think about you, drive, resiliency, adaptability, and humility. We talked about a few of them during the episode. I do truly think about the word integrity, about doing what’s right, understanding the greater purpose, understanding where you fit in. How do I position my life, position my actions to do right in the world and not only talk about it but show it, do it, and set an example?

I truly appreciate you joining me. I did enjoy the book. I love the perspective that you have. Thanks for helping us kick off 2022 in the early episodes here in January to tackle some of the controversial issues that are out there and some of the difficult conversations. We got to have them. It doesn’t matter where you fall in this conversation. It’s not necessarily always about taking a stand. Educate yourself. Learn more. Identify the different perspectives. Our goal here is exactly what you talked about. We might not have all the answers but if we learn about it, will we make the world a better place? That’s our goal. Thanks for joining me.

There are some things we talked about that are controversial. For anybody out there, please contact me via Twitter or Facebook. Contact Fran and he’ll give you my email address. All that is fine, I would love for you to read at least the epilogue of the book. I will even provide the epilogue for free by email via PDF. Read the epilogue at least and decide if you want to read the whole book.

Engage with the arguments in a real way. We put a lot of work into it. We put in a lot of thought and empathy. This is about serving veterans and helping them have better lives. I don’t have a political ax to grind here. I’m trying to make veterans have a better life. I welcome your feedback and read the epilogue, for sure. I’ll send it to you for free.

The book is Wounding Warriors. Dan Gade is the author. Check it out.

Thanks, Fran.

Thanks so much.