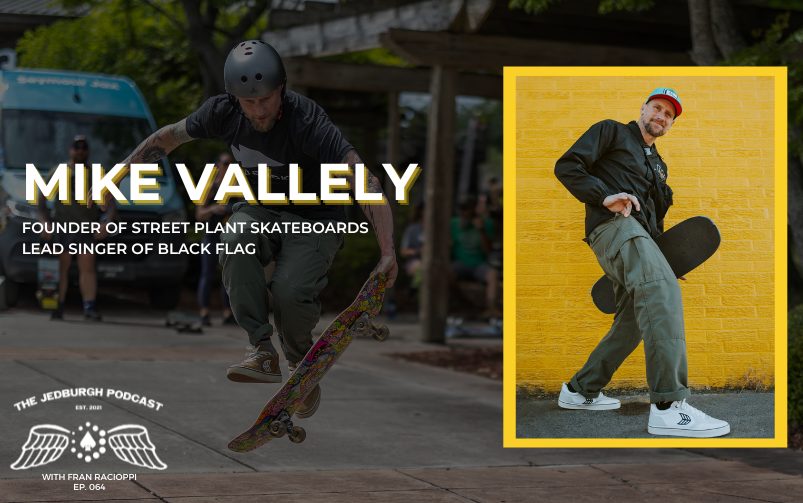

Some icons dominate multiple industries, leaving their mark not on just one part of society, but on all of society. Mike Vallely is the Founder of Street Plant Skateboards and the lead singer of rock band Black Flag.

Mike revolutionized the way society embraces skateboarding and skateboarding culture while he built a side career as a singer, playing with some of punk’s greatest artists.

Mike joined Fran Racioppi on the last day of the GORUCK Games to share his personal story, how he had to borrow skateboards to teach himself to ride, why going as hard as you can whenever you have a chance is a recipe for success, and what he has learned leading generations of punk rockers and skateboarders to skate, create and enjoy.

—

Mike Vallely is an American-born skateboarder and musician. He started skateboarding in 1984 at age 14 and turned professional in 1987. He is a pioneer of street skating and the owner of Street Plant Skateboards. He has been writing and performing music since 1985. In 2014 he became the 5th vocalist for Black Flag. In 2021 he was inducted into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame, and he is currently touring with his band Mike Vallely And The Complete Disaster.

Mike Vallely is an American-born skateboarder and musician. He started skateboarding in 1984 at age 14 and turned professional in 1987. He is a pioneer of street skating and the owner of Street Plant Skateboards. He has been writing and performing music since 1985. In 2014 he became the 5th vocalist for Black Flag. In 2021 he was inducted into the Skateboarding Hall of Fame, and he is currently touring with his band Mike Vallely And The Complete Disaster.

Icons exist in every industry, on every team and in any organization. Icons set the example, develop trends and lead others as they innovate and drive their communities forward. Many icons dominate a single industry like entrepreneurs, athletics and journalism but some icons dominate multiple industries. They leave their mark, not just on one part of society but on all of society.

Mike Vallely is this type of icon. I met Mike on the first night of Sandlot JAX at GORUCK Games. Mike or Mike V as he’s most well known is the Founder of Street Plant Skateboards. He’s also the lead singer of the punk rock band Black Flag. Michael is responsible for taking skateboarding mainstream. He revolutionized the way society embraced skateboarding and the skateboarding culture.

He led the innovation of the boards themselves because he rode harder and pushed tricks further than anyone who had come before him. All the while, he built a side career as a singer. He played with some of the greatest rock and punk artists ever until he landed a shot with Black Flag, one of the greatest punk rock bands in history.

Mike joined me in the Land Rover Ambulance on the last day of the GORUCK Games to share his story. He talked about how he had to borrow skateboards to teach himself how to ride by going as hard as he can whenever he can, his recipe for success and what he learned by leading generations of punk rockers and skateboarders to be the best that they can be.

This interview is our longest to date but it went by the fastest. I was impressed with Mike’s success but I was more impressed with his passion, honesty and generosity. Check out our videos and our pictures from this episode and the entire Sandlot event on YouTube, Instagram, LinkedIn or Twitter. We will see you there.

—

Mike, welcome to The Jedburgh Podcast.

Thank you, Fran. It’s good to be here.

Fran and Mike Vallely at Sandlot Jax

We’re in the back of the Land Rover. We’re at Sandlot JAX. I met you when we were at the kickoff concert. We had an amazing conversation about where we are in the world, your career as a musician and in skateboarding, the entrepreneurial spirit behind that and how you’ve changed both of those industries. I sincerely appreciate you taking the time out of your day. There’s a lot to see up there but I’m going to steal you in the back of this hot ass ambulance. We’re going to talk about your story.

No worries. It’s an honor to be here. Meeting you the other night was cool. You sharing a bit of your story with me was so relatable and the transitioning from one life to the next life. You did it in a very difficult period but I still got it. I felt blessed that you shared that with me. I appreciated it. When you asked me to come on the show, it’s like, “This guy already has opened his heart to me.”

Let’s talk about growing up because I want to take it back to the beginning. Sometimes in these conversations, we got to start now and back it in but it’s important for you that we start at the beginning. You’re in California. You grew up though and were born in Edison, New Jersey, which is not far from where I am because I’m in Southern Connecticut. It’s certainly different than moving out to California. You grew up playing baseball and then you got into skateboarding. Your parents bought you a skateboard. It changed your life. Why?

I feel like my life before I discovered skateboarding doesn’t even count. In the big ways, it doesn’t count. There are so many great stories and amazing experiences that happened before I started skating. It’s when I started skating that I felt that I took my first real breaths, stepped outside of the prescribed way of life and started living my life. I played baseball right before I started skating. The main sport that I was involved in was wrestling. I had been wrestling in junior high and on a rec team.

“It was when I started skating that I felt that I actually took my first real breaths.”

The high school coach had been scouting me for a little bit. My rec coach liked me and my junior high coach didn’t see any value in me but the high school coach always did. He thought that these guys were misusing and mismanaging me. He always would come to me on the side, “I can’t wait to get you.” I remember I had started skating already. I saw him in the school hallway and he said, “The first wrestling practice is this week.” I said, “Coach, I’m not going to wrestle this year. I’m skateboarding.”

How did he take that?

[bctt tweet=”Step outside of the prescribed way of life and started living your own life.” username=”talentwargroup”]

He slapped me in the face.

You could do that back then.

The coach has always slapped me. If they wanted to motivate me before a match, they would smack me in the face and then I would go out and terrorize some kids. It worked. I was like, “I’ll be at practice,” but I had chosen my destiny was skateboarding. I already knew that in my core. To back it up, it was that same school year. On the first day of school, I was walking down the school hallway. I reinvented myself over the summer of my freshman year of high school.

I decided I was going to become a punk rocker. I did not know what punk rock was. I had seen a few films where there was a minor character that was punk. I had seen some videos on MTV with people up here to look punk. I knew that there was something more than what was on the radio or the mainstream media. I didn’t know how to access it but I knew it was there and it was for me. It’s not even that it was for me. The idea that there was something else was meaningful to me.

I wanted to figure out, “Where do you learn about this stuff?” I didn’t know. My only move going into my freshman year of high school was to spike my hair. I got this jar of Dippity Do and spiked my hair. It doesn’t sound like that big a deal but it was radical in 1984. In Edison, New Jersey, this was a radical move considering that previous to that moment, I had blended into the gray of the school walls. I had stepped outside and painted a target on myself.

On my first day of school, I’m walking down the hallway and I see some real punk rockers. They’re the real deal. Somehow they got the information and had access to it. They knew what was going on. They saw me and surrounded me in a semi-circle. It was very threatening. They said, “Are you punk?” I was like, “Yeah.” They’re like, “What bands do you like?” I didn’t know anything but I looked at their t-shirts.

One guy had a shirt that said Dead Kennedys. I figured that’s a band. I was like, “Dead Kennedys.” He said, “What other bands do you like?” Another guy had a shirt that said Black Flag. I said, “Black Flag.” He said, “What other bands do you like?” A guy had a shirt that had a big Misfits skull on it. It didn’t say Misfits. It was just a skull. I was like, “That band with the big skull.” They were like, “Misfits. What other bands do you like?”

The other guy had a Three Stooges shirt on. I knew it was a TV program but I thought, “Is it a band too?” I looked at his shirt. He looked at me with pleading in his eyes, “Don’t say it.” It suddenly became so obvious that I didn’t know what I was talking about. The leader of the group goes, “You don’t know anything, do you?” I said no. He goes, “That’s cool. Come with us.” It’s the coolest words ever spoken to me. They took me right in.

“That’s cool, come with us. The coolest f***ing words ever spoken to me.”

That day after school, I went to this guy’s house and down in his basement. It was better than any movie set director has ever created. His basement punk rock bedroom was insane. The posters, musical instruments, skateboards and all this stuff were all over the place. It was like, “Somebody set this up.” I went in there and he’s like, “We’re going to make you a mixtape.” He and his buddy started working. They put some vinyl on and started recording songs.

He’s like, “You’ve got to lose those spikes.” He sat me down and shaved my head with clippers. He buzzed my hair off. It was difficult because I had so much Dippity Do. He tore the hair out of my head. They gave me this mixtape, shaved my head and then told me, “You have to get a skateboard.” I was like, “I had seen skateboarding before.”

Have you ever skateboarded?

A kid I had hung out with over the previous summer had a plastic toy skateboard. I had stood on that with him. We tried to skate it but we had no real frame of reference for what we were doing. We were just pushing around town. Previous to that, I tried skateboarding in sixth grade but the streets in my town were so rough. Now I know they weren’t good wheels but I tried to skate on the street. My teeth were rattling and the vibrations were going up through my legs. I was like, “This isn’t even fun.”

I never pursued it but these guys were like, “You have to get a skateboard.” I didn’t have the right entry point ever. It had previously spoken to me but there’s something about the energy at this time that was more like, “This is real.” With the way that they talked about it and the way that they were presenting it to me, I was like, “This is important stuff.” I identified that something in me was feeling like, “They’re right. I’ve got to get a skateboard.”

I said, “I don’t know anything about skateboarding.” The one guy who shaved my head and made me the mixtape was like, “You have to talk to my brother. My brother knows everything about skateboarding. He’s got all of the skateboard magazines.” I said, “They have skateboard magazines.” He’s like, “It’s called Thrasher.” I was like, “That’s amazing.” If you never heard the word before, it was suddenly a word that made sense.

I had thought skateboarding was super tan dudes without shirts on and barefoot doing 360s or cruising down by the beach. There were always palm trees in the visions. Suddenly, he said, “Thrasher.” I was like, “I understand that. That’s not California necessarily. That’s anywhere.” I had a deeper understanding. The word itself opened my open my mind up. I was like, “I have to get into this.”

His brother was a year younger than me. I knew his brother from around town. He never liked me. He had never been in any fights or anything but there has always been neighborhood stuff. It’s like, “I don’t like that guy. He doesn’t like me.” I was like, “That’s water under the bridge. This dude has got Thrasher Magazine. I’m going to go pay him a visit.” I go to his house and knock on his door. He comes to the door. This is the next day after school.

He’s like, “My brother’s not here.” I go, “I’m not here to see your brother. I’m here to see Thrasher Magazines.” He’s like, “Why?” I go, “It’s because I got to see Thrasher Magazines.” He’s like, “This is such a bother. Hold on a second.” He goes back into his house and comes back to the door. I’m standing outside of the screen door and he’s standing on the inside of the screen door. He holds up the magazine and starts turning the pages. I can’t touch it. I can’t even be in the same room. There was a barrier.

My frame of reference for skateboarding was people doing 360s or handstands barefoot or something. Suddenly, I’m seeing pictures of guys in the air off of ramps. The boards are big. They have amazing artwork on them. The pages are going by so fast. My mind is getting blown with every page but he won’t stop. He gets to the middle of the magazine. There’s an article in the middle of the magazine about this newer style of skating called street skating. At the time, it was called street style.

I call this an over the rainbow moment because the 360s on the beach under the palm trees barefooted was not relatable. Guys in the air on big ramps were not relatable but very exciting. Suddenly, pictures of guys skating in an environment that was right in front of me and right outside the backdoor he was standing at. My life before that moment was in black and white or sepia-toned.

“My life before that moment was in black and white, or sepia tone. And then I saw these pictures of guys skating in the streets.”

I saw these pictures of guys skating in the streets using an environment and obstacles that were every day like stairs, benches, ledges, cars, walls and curbs. My life suddenly blew wide open. It was right into full-blown Technicolor. He’s turning the pages super fast and I see a guy flying in the air. It looks like he’s flying over a cop car or something. He goes, “He’s jumping off the car.” I said, “I could do that.” He says, “This guy is a professional. You can’t do that.” I say, “I could do that.”

He was like, “Really?” He puts the magazine down, goes back into his house and comes walking out with his skateboard. The only board I had ever stood on was a plastic toy store skateboard. He comes out with this full-sized pro model. Christian Hosoi in the Rising Son has the same skateboard. It’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen in my life. He puts it in my hand and he’s like, “Do it.”

Right at the top of his driveway is his grandfather’s car. I walk over there, climb on top of the car, jump off the car and try to land on the skateboard. I ate crap. I fully slammed forward. I’ve been skating for a long time. My leading elbow or my left elbow has seen most of the damage that could be dished out. This was the first time. I piled right into the asphalt. His driveway was paved. It was a gravel pit. It was loose and unforgiving.

I had pieces of asphalt stuck in my arm. There were little dots of blood all over the place and one main cut that started bleeding. He looked at me. I got up and was like, “I fell forward. I’ll adjust my weight.” I started trying to calculate how to do this. I got back up on the car and he’s like, “I can’t believe you’re doing this again.” I jump again and fall backward this time. I do a Wilson and the board shoots out. I was like, “That’s too far back. I’ve got to try to find that middle part.”

I try it 5, 10 or 15 times maybe. I land one and ride down his driveway. One of the reasons I had never liked him and had never seen eye to eye with him is because he was always the collector of cool. He had Thrasher Magazine. He knew about this stuff. How? It wasn’t accessible to a common kid like me. He was above all of us. I was like, “That’s irritating.” As long as I’ve known him, he has always been cool but this was the one moment I saw him come unhinged when I jumped off his grandfather’s car.

He started jumping up and down. He couldn’t believe it. His experience with skateboarding until that moment was the pictures in the magazine. Suddenly, he saw it happen live in front of his eyes. He was like, “You’re a skater. You’ve got to come with me. I’m going to introduce you to the other skaters.” I was like, “Is there more than you and me?” He’s like, “There’s a bunch of guys that skate.”

I had no idea that any of this was happening in my town. We go across town. The whole way across town, we’re sharing his board and skating. I’m picking the board up and finding stuff to jump off of. I was jumping off of everything. As we were moving through town, I was getting better and figuring it out. We get to this big, wide and open parking lot. It’s a great place to skate but it’s brand new pavement. There are probably ten kids skating in the parking lot but there’s nothing else around.

[bctt tweet=”Imagination and fearlessness are what can make you unique.” username=”talentwargroup”]

We get there. As we’re walking up, the other kids see him coming. He’s their friend. They see me. We have never been friends. I’m not friends with them. I don’t know them necessarily but they know who I am because of stuff around the neighborhood. They’re looking at him like, “What are you doing bringing that dude here?” He’s like, “It’s cool. You’ve got to see what he can do.”

He hands me the board. There’s nothing to jump off of so I run, jump into the air and land on it. No one seems impressed. He thought this was going to land big and I thought so too, “This is my end.” Apparently, between the day before when he had been hanging out with them and now, the best local skater in town or this little kid had already learned to do it.

He could run, jump and land on the board. When I did it, the little kid comes over, skates over, runs, jumps and makes eye contact with me while he was doing it like it was nothing. I was presented as a challenger to his throne. It was like, “You’re back at the bottom of the stairs.” What I thought was my entry point into a peer group and a subculture, I was suddenly standing there. They all were skating and paying no attention to me. I was standing there. I didn’t have a board. I stood around for a while.

I jumped off his grandfather’s car. He had been celebrating me half an hour before. He didn’t even look at me now. I was hanging out. One kid finally sits down and I was like, “Can I try your board?” He’s like, “No.” The big thing at that time in the ’80s was no one wanted their board scratched. He’s like, “Don’t scratch it.” He pushes it over. What we find out is that they’re meant to be scratched. At that time, everyone had plastic rails, plastic nose guards and plastic tail guards.

They wanted to protect the art on the bottom, which I understand. The art is beautiful but they’re meant to be destroyed. These kids were like, “Don’t scratch it.” That was the real big thing. I get on it and realize, “I probably have a limited amount of time with this skateboard.” As soon as I got on it, I was animalistic. I was going crazy. It was like a puppy let loose out of a cage. It’s cute for five seconds and then it’s wrangling that thing up and going crazy.

He’s like, “Give me my board back.” I hung out until the evening. It was like that. I tried to ask if I could use someone’s board. They would push it over, “Don’t scratch it.” I would go crazy for twenty seconds. They would take it back, “Get out of here.” That became my whole mission. I would every day after school go and stand around while these guys skated. They started moving through town. They would skate from Point A to Point B.

I would jog behind them as they were skating, wait until somebody stopped and asked them if I could borrow their board. I got good at maximizing 30 seconds of time. I would crunch down to 30 seconds of what they had spent all day doing and go animalistic on the thing. People always talk about how I have this aggressive skate style. It probably has its roots there. I would thrash that. The word Thrasher was stuck in my head. I was like, “It’s time to thrash. Get on and go crazy.”

“I would crunch down into the 30 seconds what they had spent all day doing…I would just go animalistic on the thing.”

This went on for this went on for months. The very first day that I got into skating, I went home and told my parents, “I have to get a skateboard.” They were like, “There’s no way.” They were against it. They saw it as a pointless activity. Also, they were concerned about me getting hurt. They were saying, “If you get hurt playing sports, there’s some honor in that. If you get hurt doing something that has no end game and seems pointless, that’s stupid.”

At that point, skateboarding wasn’t as big as it is. It hadn’t become so relevant.

It was in 1984. That’s when the growth cycle began. It was starting to explode. That’s how we even became aware of it in Edison, New Jersey. The magazine existed. The pros like Tony Hawk, Steve Caballero and Christian Hosoi started to bleed out from Southern California. It was attractive to kids all over the country and the world but it was still so new. No one knew much about it. My parents were being my parents. I explained to them that this was important to me.

A lot of things have been important to me throughout my childhood. I had a bicycle rusting in the backyard. They have been down that road before. They have been down that road before but I give my parents a lot of credit at the same time. They were very aware that there was something different in my voice, posture, body language and attitude. They were very against it but they also realized, “If we don’t help facilitate this, he’s going to do it anyway. It’s going to be a bone of contention between us.” My parents were good at being parents.

We made a deal that didn’t stick on my end about grades and all this other stuff. “We will get you a skateboard.” I didn’t get the skateboard until Christmas morning. That’s a whole other story. The skateboard is delivered. I mail-ordered it from California. It was delivered in November but my mom put it in the closet and wouldn’t let me have it until Christmas morning.

I was running around and maximizing my 30 seconds. When I finally got my board on Christmas morning, that was it. It was like, “I could skate as much as I wanted.” I did. I skated more than anybody I’ve ever known of. I skated before school in the morning and skated to school. Between classes passing, I would open my locker, pull my skateboard out, stand on it and put it back.

I would skate during lunch and after school. I would meet up with the other skaters, skate with them, go home for dinner, skate after dinner and skate until it was bedtime. After bed, I would sneak out of my house and skate. I would sleep with my skateboard. Suddenly, the kid that was irritating, a pain in the ass, bothering the other skaters and looking like a fool running behind them and begging for the skateboard was skating so much that I surpassed all of them in the ability on a skateboard immediately.

The quality or the character that I had or whatever it is in me that made me jump off the car without ever even knowing what I was doing also played a big role in my skating and moving past other people very quickly. There were plenty of other kids that were skating at the time that was so much more athletically gifted or talented.

We choose to develop these things but some people do seem to have a knack for things athletically over others. Some of these kids were good athletes, to begin with. Skating looked like it came easy to them but my more wild style approach was more beneficial than athletic talent. I had enough athleticism but it was mixed with enough imagination and fearlessness that made my skating unique even at the beginning in my neighborhood.

A couple of years later, you get seen in the parking lot. That’s when the opportunity to become a professional skater kicks in.

I was lucky that first day meeting those guys in the school hallway and them saying, “Come with us.” In the first few months of getting into skating and even before I had my board there, I had mail-ordered my board, not because of my skateboard friends but my punk rock friends. They encouraged me to go that route because that’s how they all had gotten their boards. They had a friend. It seemed like a racket now. He was like, “I’ll mail-order your board for you.” I got pressured to go.

It turned out that there was a skate shop a couple of towns over from us. It was a roller skate shop that had carried skateboards. For the time, that would be a core retailer for skateboarding. We went in there pretty early on to browse and look around. The people there were so rude to us. I couldn’t believe it. I was like, “I’ll never buy something from these people and spend my money here.”

We heard about another skate shop at the Woodbridge Mall in Woodbridge, New Jersey but it was like a California culture store or a bikini store. It was called Freestyle. I had walked past that store many times in the mall. I had never seen the skateboards and I had never gone in there because I just see bikinis. As a preteen or teenager, I wouldn’t even look. We heard, “Freestyle carries skateboards.”

This is in the autumn of ’84 before I had my board. We went in there and walked in with our eyes glued to the ground because we were walking past the bikini racks, “Where are the skateboards?” We wouldn’t lift our eyes until we saw wood. As we’re walking in, there’s this much bigger and older than us Black dude. He looked like a new wave rocker. He had these glasses that had wingtips and a flat top that extended out and curved up a little bit.

He looked like he could have been in some cool bands or something. That was very intimidating too. We were like, “Who’s this guy? Is he going to be like the guys at the skate shop that we were previously in?” He’s like, “What’s up? Where are you from?” We were like, “We’re from Edison.” He’s like, “What bands are you listening to? Where have you been skating? Do you have spots? I was in California.”

He starts immediately interacting with us. We realized right away that this guy knows skateboarding. He knows it more than being well-read in a magazine. He has skated the old skate parks. He has been to California. He has been around professionals. He knows skateboarding from the mid-’70s and on. He’s cool. He’s a nice guy. He appears to care about us, the punk-ass kids in his store.

That guy became an immediate friend of ours. He became my mentor. His name is Rodney Smith. He had a car. He knew other skaters in other towns. Suddenly, we’re in the backseat of his car zipping around and going to skate. He’s showing us the ropes. He took a particular interest in me, especially once I had my board. He encouraged me and told me, “You can do it.”

Street skating was so young and new. Even though there had been people that had been pioneering street skating, kids all over the entire world were also participating in the pioneering of street skating. It was such a new phenomenon. We took to it so quickly because we had the environment right outside our doors. He saw it immediately in me. He believed I had the potential to make a difference outside of my local area and to potentially become a sponsored or professional skater.

He took an active role in mentoring me. He was a good skater. He wasn’t a great skater but he knew skateboarding. Some people are born teachers. He could help me with my skating even if he couldn’t do what I was doing. He knew how to help me, “If you want to land that.” He gave me pointers and looked out for me too because the culture starts leaning negatively. It’s easy to get caught up in that. He would be like, “You skate. It’s about the act. The other stuff is noise. You don’t pay attention to it.”

[bctt tweet=”Skating is all about the act. The rest is just noise.” username=”talentwargroup”]

He would get very parent-like with me. He’s the only one that got away with calling me Michael, “Michael, you’re better than that. Get away from the clowns.” That was important early on. That led up to me getting sponsored. He was there when I got sponsored. I started skating in September of 1984. I got my first board on Christmas morning of 1984. In June 1986, I got sponsored and got on the Bones Brigade.

You were putting the work in. I want to ask about skateboard design because from there, you launched this professional career, which defines the rest of your life. We’re going to talk about music. Skateboard design has come a long way. You were very instrumental in crafting what the next generation of skateboard design looked like. Can you talk a bit about that?

In the mid-’80s, most of the skateboards that were being manufactured, the names on them were Hawk, Caballero, Philips, Hosoi and McGill. These guys skate at ramps. The boards sold well. They had amazing artwork on them but as we took these boards into the streets, we realized they had some limitations. Even though the boards that were being manufactured were selling great, those of us that were starting to try to push the envelope saw that the nose needs to be bigger, the wheelbase needs to be shorter or this board is too wide.

Skating was advancing faster in the streets than it was on the manufacturing end of things. At one point, I determined I needed a bigger nose on my board. I drilled the nose back or had someone do it for me because I can’t do anything like that. We had a good skate shop opened up in our town. Some good older guys owned it. They weren’t skaters but they owned a hunting and fishing store. They started carrying skateboards and then became real advocates for skateboarding.

They were good dudes. I was like, “I need a bigger nose.” The old World War II vet that was building the boards was like, “I’ll draw that.” This guy Tony was great. He helped me with that stuff. Some older guy or someone’s grandpa was tinkering with skateboard design in a skate shop because the need was there and the kids were saying, “We need this.” He was helping me.

Stacy Peralta who was our team leader on the Bones Brigade saw my board one time with the nose drilled back. He’s like, “What’s this?” I go, “I need a bigger nose because I was doing tricks off the nose or onto the nose. The boards before with a 1-inch or 2-inch nose, you couldn’t use the nose in that way.” He got mad. He wasn’t mad at me. He was mad that he realized that what we were doing in the streets was progressing faster than they could keep up as a manufacturer.

That is what I know that I’ve had the perspective. I’ve been doing this a long time. He knew that was going to be problematic and the next thing in skating was going to come from us and it wasn’t controllable. That’s hard when you’re running a business and suddenly the inmates are running the assignment. I could sense he’s a very bright guy and wide-eyed. He gets it all.

I also sensed his frustration even if I couldn’t have articulated it then or understood it. I knew, “This presented a major problem to this guy.” The problem would come to a head in less than a year from then. Rodney Mullen and I left the team at the same time. We went over and became part of a startup company called World Industries, which we both were given.

Rodney bought in. I was given ownership because I was a young hot skater. It’s a good look. We started developing products. They were able to do things quicker, turn them around faster and get them to the market. It was exciting. Kid skaters could grasp it. It wasn’t old. It was new. It was happening at the moment. Powell Peralta and Mike McGill were still making boards with 2-inch noses. It changed overnight.

My first board from Powell Peralta is considered one of the first boards built for street skating but it still had some limitations to it. They didn’t honor all of the things I want to do with that board because they thought that they knew better. It was important that they establish, “We’re the manufacturer. You’re the skater.” They would probably say that now, “It was a mistake.”

I wanted a bigger nose on my production model board and it didn’t have it because it wasn’t proven in the marketplace yet but it was proven in the streets. What made World Industries happen so fast is that they took what was proven in the streets and adapted that immediately to their business model. It was exciting for me. Suddenly, I was involved in a company and was a top skater at the time. Out of that, we developed a board that was called the Barnyard. It’s a celebrated skateboard.

It’s considered the granddaddy of the modern skateboard because that board was a large freestyle board intended to be symmetrical, have a large nose and be ridden in both directions. No board before that was built with the same intention. At the core of skateboarding, lots of people argue about this stuff, “The Double Vision came first,” but all that matters is that this is the board that stuck and was celebrated. It wasn’t just the shape of the board. It was a revolution in so many different ways.

It was a revolution in the arts. There had never been art like this on a skateboard before. The shape was shaped by Rodney Mullen who is a freestyler. He was putting his fingerprint on street skating. He would go on to become one of the most famous street skaters as well. Also, the fact that as a skater, I had left the biggest manufacturer in the business and gone over to this company and become an owner of this company and was putting my chin out front with a radical design in art and shape.

I was pushing it forward. They could have put someone else’s name on the board at the time and it wouldn’t have made any difference. It would have been a flop perhaps but it was who I was, where I was and all those other elements added to it that made the board the board. I’ve played a role in skateboard design ever since. My favorite thing about running my skateboard company is shaping boards and trying to come up with cool and unique stuff.

I want to ask you about the artwork because the artwork in the Barnyard was revolutionary but there’s also an aspect of creativity. I bring it up because we’re fortunate to have a conversation in the lead-up to the Olympics with a guy named Lucas Foster. He was on the US Olympic Snowboarding team. He’s a rookie on the team. Four guys went on the men’s team to the Olympics. It was his first year. He grew up in Telluride with no halfpipe. He had to go find the halfpipe to be able to compete and operate at that elite level.

He was a skateboarder first. He was very influenced by skateboarding. Snowboarding is influenced by skateboarding at large and in general. The conversation we had was about creativity, something like skateboarding and snowboarding and also when you talk about board design and the artwork that goes on these. It’s all about the athlete. In skateboarding and snowboarding, it’s certainly an athlete who’s there. It allows them to represent themselves and express themselves in a certain way. He talked a bit about the importance of bringing that expression of your creativity into your style.

All of my early boards are highly collectible. They’re all celebrated as important. This is an important skateboard because it was like putting out a record. You put everything into it. The board broadly represented you. It wasn’t just a name on a skateboard. My first board from Powell Peralta featured an African elephant. Many people consider it the greatest skateboard graphic of all time. Why? The story behind getting that African elephant on that board is insane.

They wanted to give me some art that I couldn’t relate to and didn’t come from me. It wasn’t my idea. It would have been convenient for them to do whatever they wanted so they could keep me under their thumb. I don’t mean that in a negative way. They were the manufacturer. I was the young skater, “Go skate. We will take care of this.”

It was an employer-employee relationship.

I stood up for myself and the vision I had for my life and career as a very young person against people who I idolized. They were my heroes but I wasn’t going to take what I was being handed. I had to have it my way. Those same people are what inspired that attitude in me. It was a very difficult dynamic. It was hard to go through as a young person but also integral to who I am.

“I wasn’t going to take what I was being handed. I had to have it my way.”

They’re like, “Here’s your graphic.” I was like, “I’m sixteen. That’s not my graphic.” “What do you mean that’s not your graphic?” “I told you I want an African elephant.” “The artist doesn’t want to draw an African elephant. You got to take the cockroach.” I was like, “I don’t want a cockroach. It looks cool. It’s a great board. It’s not my board.” They’re looking at me like, “Who do you think you are?”

Why do you want the African elephant?

I had seen a National Geographic program about African elephants. I had stumbled upon it flipping through the channels one night. At that time, African elephants were in danger of being extinct. I had never thought about anything like that in my life before. There has been no previous moment where someone said, “We should care about animals or anything.”

There’s not one moment but I saw this thing and thought to myself, “That’s wrong.” I don’t even know that the program was ultimately trying to force me to think that. They were saying, “This is what’s happening.” I said, “That is wrong. What world would we be living in if we would allow this animal to leave it? It seems so wrong to me.” It was the first time I had any idea of animal rights.

I wouldn’t even know how to frame that. I thought, “I want to put an African elephant on my board to remind people that some things are sacred. It’s important. If the animal does go away, I still want it on my board because I want it as a memory. This existed. In our lifetime, we saw these things on TV.” I got to see them in real life later in life, which was amazing.

It was an innocent radicalism that came over me. I got hardheaded about it. I wouldn’t budge. The company kept trying to feed me different things. My board would have come out a lot sooner but it was contentious for so long and with no resolution until one day. There’s the artist VCJ. He’s the great Powell Peralta artist. He did all of the classic graphics. They tried to give me a different artist at some point, “VCJ doesn’t want to draw elephants.”

[bctt tweet=”Street skaters breathe life into dead spaces. They utilize environments in a way that had never been used before.” username=”talentwargroup”]

They started having other people. I was like, “No.” I had a very unique perspective. I became a part of the team but I had previously been a fan. I’m the only skater that got on the team that has a classic graphic that is considered part of that generation of skaters. I have my generation but those people embraced me. I’m part of their thing even though I came later. I’m the only one of them that was a fan. They did it together and came together. I was a fan and then I became a part of them.

They all wanted new artists and ideas. I was like, “I want what you have.” It was classic to me already. It was also new to them that skateboarding was exploding and that it was reaching out into the world. They kept wanting to go forward. They didn’t care about the graphic. It was like, “I’ll do a new graphic. This other company used a different style of art. We think that’s cooler. We should do that.” I was like, “VCJ’s classic graphics are the best,” but they didn’t have the same perspective.

That’s what I’m trying to say. They were in a different zone. I was a fan of it and a participant. One day, after all of this stuff, they’re trying different artists and I’m saying no and being so hardheaded. They’re like, “Who does this kid think he is?” In other ways, I thought a lot of my peers’ egos had gone crazy. Skateboarding was exploding. The events were getting bigger. The skate fans were acting weirder. I had such an idealistic idea about what the industry was and then suddenly, I saw it was just business.

I was developing a chip on my shoulder about the whole thing. I loved skating so much that I thought, “Maybe the best thing is not to be a pro skater because my idea of being a pro skater was to positively promote skating but I felt like the industry was in the way of my enjoyment of skating.” It was difficult in so many ways, especially with the graphic. One day, I was in New Jersey. I got a FedEx tube sent to me and I opened it up.

It was a drawing of an elephant with a Post-it note from VCJ on it. It said, “You were right.” I immediately called the company and talked to my team manager, Todd Hastings. I go, “What’s going on? I got this FedEx thing.” He said, “You won’t believe what’s going on over here. VCJ has sequestered himself in the art room and kicked everyone else out. He’s got the windows covered. You can’t see in. There are drawings of elephants everywhere.”

Over a couple of months, I would get another drawing sent to me. He said, “This isn’t it but it’s close.” There were so many different variations of elephant themes and graphics. Right before Christmas of ’87, I got another drawing sent to me. He said, “This is it.” It was clear. It took a while for the board to come out. The board didn’t come out until the summer of ’88. I fought for that.

To get back to the original question, that’s why that board matters so much to me. It’s because it mattered so much to me that it matters to other people. Every board that I put out since then had the same intent and energy. It was like putting out a record. In the early to mid-’90s, that all started to change. I still tried to have a fingerprint on everything I was doing but the industry went generic. Board shapes became generic.

The company I was skating for did away with pro models. It was just company label boards. When I returned to have a pro model in the late ’90s, I had my last pro model. That was a design that represented what I wanted to represent. A few years later, I signed with Element Skateboards. When I signed with them, I licensed my name to them. I had no control over any skateboard graphics.

It was important to them that I had no control because what I had done in 1987 and 1988 opened a can of worms for every pro skater. I was the example. By the early 2000s when skateboarding sales were booming, it was like, “We can’t afford to have these dudes coming in and dictating what they want on their boards. We need to knock out a new graphic every couple of months.” It was turn-and-burn. It’s like, “We’re going to put your name on whatever we want.” I would go into skate shops in the early 2000s and people would be like, “We got your new model.”

I would look up and go, “That’s my new model. I had no connection to it. There’s no soul.” Everyone’s first board is important to them but I’ll have people email me, “I started skating in 2004.” They will send me the name of the model. I don’t know what that means. They said, “Do you know how where I could find one?” I’m like, “I don’t even know what it is and what you’re talking about.” When I started my company, it was a purposeful return to being very sincere and earnest in creating boards that had a heart and a soul.

“But when I started my company it was a purposeful return to being very sincere and earnest in creating boards that had a heart and soul.”

You started Street Plant without outside funding. It’s internal and family.

Since the early ’90s, I had been in and out of so many different business deals as a “part-owner” of the company. What I found out is that in those kinds of arrangements, they hand you some ego-inflating piece of paper that says you own something. All they ever wanted was to use my name for as long as they could extract some money out of it and go skate.

In the early ’90s, I thought I needed to segue out of professional skating and I wanted to be on the other side. No one saw value in me stepping away from skating. There was always more value to them. Ultimately, if I reflect on it, there was more value to me in being on my board but none of those situations ever played out in any positive way.

When we decided to start Street Plant, it was the end of the line. I had already done it all. I’ve been in every possible business scenario that you could be in as a professional skater. I ultimately decided, “If I’m going to do this and it’s real, then I’m going to use the Street Plant name, which is a name that’s mine. That’s me.”

Where did it come from?

That’s the trick that I pioneered when I started. T represents my idealistic or philosophic view of skating. What we did as street skaters when street skating started was breathe life into dead space and utilize an environment in a way that it had never been used before. It was that flower breaking up through a piece of concrete or asphalt. It was beauty and life in an adamant environment.

The trick itself, Street Plant, is what I was known for early on. The was so personal to me that I realized, “I can’t have investors, partners, distributors or anybody that’s going to potentially put the nail in this thing’s coffin. If that happens, it has to be all me.” I didn’t have any money. The money had run out many years before.

It’s the hardest part of starting a business.

I didn’t know. I was so afraid and unsure of what to do. I had no confidence in myself. I lost all of it. As I lost my money and career, I also lost my confidence in myself and the total identity of who I was. I couldn’t call on anything I had previously done. I go, “That’s who I am.” I was lost at sea. What I did is I jumped off of a cruise ship. I had left the party and thought I could make it on my own but it turns out if you jump off the ship, the water is like cement.

You break into a million tiny little pieces. If you can somehow get to the shore, then you have to start all over. There I was on the shore. I thought I was alone and then the most amazing thing happened. My kids, my wife and the people who I love and who loved me said, “You’re not alone. We could do this together.” I was like, “What?” I had never pushed skating on my family. I did it. It was my career but I tried to leave it.

When I came off the road and came back from an event, I was a dad and a husband. I wasn’t a skateboarder. I was just there. Although they had access to it and front row seats to a lot of it, the culture never negatively penetrated their lives. It was like, “This is what dad did.” I wanted my kids to live their lives. Skateboarding was not supposed to be a part of anything they were going to be interested in.

My oldest daughter, Emily, had finished school. She’s like, “Dad, do you think these other people that own or run companies are smarter than you?” I was like, “Pretty much, I do.” She’s like, “They’re not. If you need help, I’ll help you. I went to school for this stuff.” All I needed was a little help, encouragement and someone to believe in me. That made the biggest difference. I had no money. I was like, “Do you have any money?” She didn’t have any money.

“All I really needed was a little help and a little encouragement…and someone to believe in me.”

She’s like, “You spent all that in sending me to college.”

The one thing I had was a name in the sport and some goodwill. I made one phone call to a manufacturer who I had worked with through the years and had always had a good relationship with. I said, “If I bought some boards, could I have 30 days to pay you back?” He’s like, “I don’t do terms. What are you thinking?” I said, “I got this concept for this company. My family and I are going to run it ourselves out of our house.” He was also concerned, “Who are you working with? What shady people are you bringing?” I was like, “There’s none. It’s me and Ann. You know us and our kids.” He’s like, “We can do that.” He gave me the 30 days and I paid him back in 15. We were off and running.

The whole time you’re building and moving through your career in skateboarding, you have this almost parallel world of music. We were joking about getting kicked out of your first band because you were skateboarding too much. It starts to come to fruition. You get introduced to Black Flag in 2003 and then in 2013. I have to ask the question because I don’t know much about the story. How do you end up firing someone mid-show? There’s probably a backstory.

First off, I probably have said numerous times that I got kicked out of my first band for skating too much. It’s an unfair thing to say. We had this band called Resistance. There had been a singer in the band before me. The guy who’s the singer in the band before me is the guy who mail-ordered my first board. He was a great frontman for the band but he was wild and unpredictable.

[bctt tweet=”Rise above. You have the power. You are born with the chance to rise above.” username=”talentwargroup”]

The guys in the band were serious musicians. It wasn’t like, “We’re a local punk band.” They wanted to do something real with the band. They were they were ambitious. If you put the word ambitious in front of skateboarding or punk rock music, then suddenly that’s an oxymoron but it’s not. Why would you not be ambitious? Why do anything?

The culture says, “You were ambitious. That’s lame.” Take a hike. These guys were ambitious. The singer was great but unpredictable. They wanted to replace him. They were my friends. The band was great. I was like, “I want the opportunity.” I was only fifteen. They were like, “You’re a little young.” I went in for a tryout with my energy.

You sang outside of the shower.

I did a chorus and stuff but I was horrible and still horrible. They were like, “This is cool. We can do this.” They had a show booked. They were opening up for the band 7 Seconds and Aggression. It was a big show for our area. We were the opener. The night of the show, I was grounded.

What did you do?

What I do remember is I had to sneak out of my house and run two towns over to play the show. I snuck out of my house and ran from Edison all through Highland Park and into New Brunswick to the venue. I ran up the stairs in time to perform the set. The set went great. People loved it. The other bands that were there loved it. They were like, “This kid is great.” People were patting me on the shoulder. It felt good but our guitar player was a bit older.

It was his band. He was writing the songs. All that he could process about the whole thing was, “You had to sneak out of your house and run here. That can’t work. We’re trying to be a real band. This isn’t going to work.” A lot of the clubs were older. I was too young to even play the shows. He’s like, “You love skateboarding too much.” I wanted to do both. I always joke, “I got kicked out for skateboarding too much,” but it’s unfair to them.

Running to the show is a better story.

We all thought, “This could be great,” but I was a touch young and I had other things happening in my life that were going to keep the band from moving as fast as it wanted to move.

You didn’t walk away from it. You had Mike V & The Rats.

Ever since then, I tried to stay active in music but I was never able to get a band together. It’s weird. Once I had success in skateboarding if I would talk to a musician and say, “We should play,” they never took me seriously. They’re like, “You’re a pro skater,” but pro skaters had bands.

You could do a few things at once.

I always felt like no one took me that seriously. I had always written poems or song lyrics. I thought I was writing good stuff. I was looking for an outlet for it but I could never find one. In 2001, I was doing a wheel company. One of the guys that were working at the wheel company was a great musician. He had a great band. I went and saw them play. I was so jealous when I saw them. I was like, “These guys are so great. This is exactly the band I would want to put together.”

I said, “I love your band. If you ever want to do something, I would like it.” He’s like, “I’ve got a band. Why would I want to do something else?” It wasn’t much long after that when he reached out to me. He goes, “I wrote some songs. Do you want to give him them listen and see if you could come up with some words for them?” I was like, “Yes.” That became Mike V & The Rats.

I was introduced to Black Flag that first day in September of ’84. When I went down to the basement and got my head shaved, those guys made me a mixed tape. The first song on the mixtape was Black Flag’s Rise Above. There’s other great music on that mixtape but I didn’t need to hear any of it. Rise Above became the mantra of my life. It was so optimistic and so much of punk rock is so negative and victimology.

“Rise Above became the mantra of my life.”

This was the song Rise Above, “You have the power. We are born with the chance. I am going to have my chance.” They’re very powerful lyrics. I loved the band. A month later, I went with those same guys I was in the band with before they had their band. We went to Trenton, New Jersey to see Black Flag play. I was fourteen years old. I go to Trenton, New Jersey to see Black Flag.

I don’t own a skateboard yet. We’re hanging out in the parking lot and tailgating. I don’t even know if we called it tailgate. It was like, “Get there early to experience the whole thing.” There were kids from all over the region like Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New York and Delaware. They have all converged in Trenton, New Jersey to see Black Flag.

Everyone was hanging out in the parking lot. Some guy gets on a skateboard and starts slashing around in the parking lot but the parking lot was poor gravelly asphalt. He’s not able to do much but something was happening. Everyone walked over and started watching this guy slash around. My buddy’s name is Keith. He shaved my head and gave me the mixed tape.

He’s standing there. He looks at the guy on the board and goes, “You should see this kid skate.” I had no idea up until that moment that any one of my friends thought anything. I didn’t even own a skateboard yet but he had seen some of those 30-second sessions that I had and he was blown away by them. I didn’t know that until he said it out loud to somebody else.

He’s like, “You should see this kid skate.” The guy pushes the board over to me and I get on it. It’s like the puppy out of the cage. I went wild on the pavement. The payment was so bad. I looked around and saw that behind the venue, there was a street and a manufacturing or industrial building of some sort. There was a sidewalk and some stairs. The street looks smooth over there so I bolted over there. Lo and behold, the entire crowd of people in the parking lot follows me over.

It was my first skate demonstration or performance. It was for a willing audience. Those kids that I skated with that I chased behind never valued my energy or what I did on the board. They thought I was a pain in the ass. This group of people wasn’t invested in skating in the same way those kids were. Skating, to them, was cool. Enthusiasm was awesome like, “Look at this guy. He’s going for it.” They could appreciate it.

Suddenly, I had an audience that was wide open to what I was doing. I started doing things on the board I had never done before. I jumped off the stairs and roll through the grass and into the street. They were cheering. My aggressive style found an audience. It’s like, “This is so cool.” I see this bucket on the sidewalk. I go over and kick it over. Everyone cheers. There’s tar in the bucket. A little bit of tar spills out. I had some new Vans. I got tar on them.

I go around, skate up, pop the board into my hand and jump over the bucket. Everyone goes crazy. I was like, “This is so awesome.” I circle back and go, “I’m going to try something I’ve never done before. I’m going to jump over bucket 180 and land back.” I’ve never done it and had this much time on a skateboard. I’m getting set up to go and everyone realizes, “This is the highlight. This is what the whole thing has been building towards.”

I’m getting serious and ready. I’m about to take off. I see the attention of the crowd shift from me to something behind me. I immediately think, “The cops are coming but I don’t care. I’m going to go anyway. The police can arrest me after I land.” I go and jump 180. In the air, I turned and looked to see what was coming behind me. Henry Rollins, the singer of Black Flag, is walking down the street and carrying two bags of groceries.

He walks up and as I land, he gets even with me and walks right past everyone quickly right into the venue. I didn’t know who he was. He was just some dude. The crowd was like, “Oh my God.” They didn’t quite put me up on their shoulders but they were patting me. We go in to see the show. It’s incredible. It was a life-affirming experience. Here I am at fourteen years old standing in front of the stage. These men get on the stage.

I had never seen live music before in my life. They come out and assaulted it. It’s unrelenting and powerful. I’ve never seen anything like it. I determined at that moment and that night, watching that band play. It was Greg Ginn, Henry Rollins, Bill Stevenson and Kira Roessler. I watched them play and determined, “Whatever I do in my life for the rest of my life, I’m doing it like that.”

[bctt tweet=”When it comes to being a musician, all that really matters is knowing that people had a good time.” username=”talentwargroup”]

You would have thought there were thousands of people in the audience. There was a spattering of some 80 maybe but they gave it everything. I had never seen anybody give it everything live and in-person right in front of my eyes. I had seen sports on TV. I had done that on the skateboard out in the street and I had done that playing sports myself but it was never older people live and in-person right in front of my eyes with that intensity.

I was like, “These guys know something that other adults don’t know. They’re doing something that other people won’t do. That’s so cool. I’ve got to be a part of something like that.” It influenced the rest of my life. Seeing Thrasher and understanding what street skating represented was the over-the-rainbow moment. Seeing Black Flag is the life-affirming moment. It’s like, “This is your life. You can write the script.” These guys are not playing Madison Square Garden.

That’s where I thought music occurred in some giant arena. They were doing it with the greatest intensity and sincerity that probably every rock act that was playing in Madison Square Garden wished they had. That’s when I realized you can do anything you want in this life. They proved it right in front of me. It was relatable and accessible. It turned me on to music. I have always loved music but this was a different experience. It was an important moment in my life.

“You can do anything you want in this life. They just proved it right in front of me.”

Going forward, I started the band Mike V & The Rats in 2001 or 2002. In 2003, Mike V & The Rats gets the opportunity to open up for Greg Ginn, the guitar player, founding member and main songwriter for Black Flag. This guy has always been a hero of ours. We had never met him. We were excited to get the gig. We’re just an opening band. We had been an opening band for other acts. We knew what that meant. You know your role. You get up there, set your stuff up, play, get off and get out of the way. We ended up doing fifteen shows opening for Greg. In the first show, the crowd is the pretty typical Southern California punk rock crowd with arms folded, scowls on their faces and backs to the wall.

We were giving it everything we got and nobody cared. Suddenly, one person comes up and stands right in front of us. They’re moving their body with their hands in the air, having a great time and enjoying the music. It’s Greg Ginn, the guy we’re opening for. I’m singing it and I’m like, “Is this real? I know it’s him. What is he doing?” We never even met most of the acts we ever opened for. They stayed in their backstage room, van or vehicle. They came to the stage and never even interacted with us.

The guy that we’re opening for is in the front row. He’s the only person. There is no row. It’s just him having a great time. He watched our whole set. When we were done, he walked right. We had some merch set up. He started to buy a t-shirt. I haven’t even met the guy. I run over and I’m like, “You don’t have to buy that. You can have it.” He’s like, “If you like a band, you support the band. I’m buying it.” I was like, “He’s a fan of our band.”

He starts talking, “You were great.” I was like, “It’s so embarrassing because when we started the band, we decided we were going to try to be like Black Flag and sound like Black Flag. You’re the inspiration for our music.” He’s like, “It’s so obvious but there are also so many other things happening. You’ve got great songs, tones songwriting and vocals.” I had never gotten feedback from anybody. My family wouldn’t even give me feedback.

We would play a show, “How was it?” “It was good.” They wouldn’t say, “You sounded great.” I had never gotten 1 ounce of positive feedback or even negative. I got nothing. There was no constructive criticism. I was dying every time we played. I knew I was giving it my all but I didn’t know if it was landing because most of the audiences and people were nice afterward usually, “That was great.”

They would shake my hand and get a picture with me or something but they would stand against the wall with their arms crossed and a scowl. It appeared that they hated us but it was just their self-image or something. I had no idea what I was doing. I had no reflection to look at. Nobody had given me any information. Here’s Greg Ginn. He’s a hero of mine. He owes me nothing but he’s like, “I loved your vocals. Here’s a fact. You’re so great at what you’re doing.”

For the sound, he’s like, “If I ever did a band like that again with that style of music, I would love to have you sing.” I was like, “What the hell?” I knew he was sincere because nobody says that. I know for certain because Greg doesn’t waste words. If he says something, he means it. I was like, “That was heavy. That was nice of him.” It made me happy that we were playing with him, excited and enthused to do our best every single night.

I was like, “This is a good dude. We’re going to do our best to open these shows up and support him.” It was fun. We had a great run opening up for him. When it was coming to an end, he told me, “The reason I’ve been doing all these shows is to prepare myself for a Black Flag reunion. That has been in the works for a while.” We were like, “There’s no way. Can we open?” He’s like, “You can’t.”

As the planning for the reunion went on, a bunch of different things started happening with ex-members and people couldn’t get on the same page. The thing started to unravel and fall apart. At a certain point, Greg called me and said, “Not all the original members are going to be doing this. It has evolved into something else. Would you be interested in doing a guest vocal set with us?”

I had told him or he had read something that the My War album was a big album for me and that I went and bought it. It was the first record I bought with my money. He’s like, “Would you want to sing that record? We have never done that. The band had never played all the songs.” I was like, “I’ll do it.” I didn’t understand and care that there was noise or politics around this with other members or even the audience.

This guy had been so kind, nice and real to me and the guys in my band that if he asked me to do it, I was in. I wasn’t going to overthink it like, “What will the magazine say?” “Screw the magazine. At face value, this guy is a righteous dude. I’m in.” I went and did it. The audience was pretty hostile about that. At one point, there was a metal trashcan set on fire with fire flying out of it and thrown at me.

There was a real sense of the threat of violence but I played the songs, sang them and gave it all I had. It was a good set of music. I got torn apart by critics and other musicians that were in the house but I know it was good. People just didn’t want it to be what it was. When it was over, we played three shows. We did two nights at the Hollywood Palladium in 2003.

The band was good with it.

We played two nights in Hollywood Palladium and then another night in more of an underground secret show in Long Beach at a punk rock bar. When it was over, I figured I’ll probably never see Greg again. I felt like the experience as a whole of bringing Black Flag back out of the closet had an overall negative feeling for him. He’s like, “I’m going to put it back in the closet and move on with my life.”

The band had never reunited up until that point because he wasn’t interested. He decided to reunite the band. Ultimately, he wanted to do it for a charity or a cause. He said, “If we’re going to do this, then it should be for a cause.” His cause was the welfare of cats. He cares a lot about stray cats. He learned that in most of these charity shows, bands make off better at charity shows than they would have at regular shows. Only a small percentage of the money brought in goes to the cause.

He determined, “That’s wrong. Every penny we make as a reunited Black Flag is going towards the cause.” That’s where the reunion unraveled. Everyone was looking for a payday. It was very shortsighted if you asked me on the behalf of the members that didn’t show up because they saw it as Greg trying to control them or the situation. Maybe that is the case but it’s his band to control and his ideas.

If you show up and it goes positive, there are plenty of paydays after that but they were like, “It’s one of Greg’s things.” I had no baggage to bring to the table. I showed up as a fan and asked to sing. I’ll do it. When the reunion was over, I pretty much figured, “This will never happen again. He’s not going to be touring anymore and doing this style of music. We’re not going to get to interact on the road in any way.” I called up this skate photographer friend of mine and said, “Could you come with me? I want to get a photo with Greg down at SST, have him sign a My War record, shake his hand and thank him.”

I figured that would be it. We went down there. He signed my record and said, “Mike, thanks for singing with us.” Greg Ginn drew the Black Flag bars on it. We took a photo. I shook his hand and said, “Thanks for everything. It was an honor to play music with you.” He goes, “I got your number. I’ll reach out to you if I ever want to do another band. If Black Flag ever happened again in the future, I would love to have you be a part of it.”

Years go by. I don’t talk to him for years. I get a call or an email, “It’s Greg. I’m not playing rock music but I want to stay in touch. If I ever do decide to do a rock band, I would love to work with you if you’re still interested. I would email back. If you ever want to do anything, I’m here.” It was years and years. It wasn’t until 2011 or 2012 that we started working on something. I performed with him in 2003. We stayed in touch the whole time. In 2012, we wrote songs.

He’s like, “I wrote some songs. Do you want to give them a listen and see if you come up with some words?” He sent me 73 tracks or something. I didn’t even know how to process that much music and where to start. He sent me so much music. I thought, “This is so real.” My bandmate, Jason, sent me three songs. There were 73 songs. I said, “I have to take a real working man approach to this.”

I would get up at 5:00 in the morning, go out to my garage and play the music. I had a notebook. I would listen to the tracks and start writing words that I thought sounded like what the music sounded like. I’ve been always writing stuff. I had other notebooks filled with song ideas. I would say, “Does that song idea match up to these words at all?” I would pull pieces from other songs. I started over time, weeks and months writing words for every single track he sent me.

How long did that take?

It was months. I finally got back to him and said, “I’ve got some words.” I didn’t tell him I wrote words for every single song. What I learned later is when he goes into the studio to record tracks, he gets into a zone, goes through all these different feelings or ideas and explores all of them. That’s how he got so many tracks. It’s an exploration. I did the same thing with the words.

I eventually went out to Texas. He had moved to Texas. He had a recording studio there. We went out there to work on the songs with him. I showed up ready to sing 73 songs and had words for all of them. He was like, “You’re the first person that has ever matched my output. I expect you to show up with ten.” I took it as, “You sent me 73. I have to.”

That’s what I thought but the expectation was ten. We started recording. We released 40-some of them. We still have unrecorded material. As we were working on the material and getting closer to thinking we’re getting somewhere with it, he’s like, “What do you think we should do? Should we put this stuff out?” I was like let’s put it out. He’s like, “As Black Flag?” I was like, “No. Let’s start a new band.”

I was intimidated by the idea of being in Black Flag. I also didn’t want to make any claim there. I thought we should do a new band but I said to him, “A lot of this material is autobiographical. It’s personal to me. I don’t think those are Black Flag songs.” We have such a great relationship. We’re getting along and vibing well in the studio. He got mad at me. He’s like, “You don’t say what Black Flag is. Black Flag is whatever we want it to be.”

It was offensive to him. I understand because I’m good friends with him and I’ve spent a lot of time with him. Greg Ginn is Black Flag. I understand that the worst thing I could say is to try to tell him what Black Flag is or should be. He’s saying to me, “We could release this as Black Flag.” I’m saying, “This isn’t Black Flag.” He said, “Who are you to say what Black Flag is?”

He’s also taking you in and showing you that you are a part of this.

He has opened the door to me and allowed me in. We still determined that we would release it as a new band. Shortly after we released it and started the process of supporting the music, he decides to reunite with Black Flag. I realized in perspective that I should have got over my hesitations and whatever my hangups were right away. I should have accepted being the singer then because we could have avoided a lot of headaches that came.

The headaches were going to come no matter what but we could be well past them now. It became clear that he was open and willing to do it. He would have brought me in as the singer but I was in a different headspace. He had reunited with one of the previous singers, Ron Reyes and decided that they were going to go out and tour as Black Flag. He asked me if our project and our band would be willing to be the opening band for Black Flag and also would I be willing to help him manage the band. We had a good relationship. He liked my style of doing things.

He’s like, “You’re in line with how I want to run stuff. Help me manage tour and manage the band.” This was at that time that we were speaking about when my career was coming to a crash. I thought I needed employment or a job. I could have probably found one in the industry but it might have also meant me continuing to put my body on the line. I was getting less comfortable with that exterior pressure. I’m okay with it if it comes from within but it’s the exterior pressure I’m not going to go for.

That would be the job requirement. The expectations would be high. Here was an opportunity to do something that I loved and thought I could be successful at. I was as successful as anyone could be in the situation. The relationship with Ron, unfortunately, broke down quickly. There’s a lot of stuff. None of it is worth getting into because it’s none of my business. Ultimately, I don’t want to put bad energy out about anybody.

Ron was great until it wasn’t great anymore. When it wasn’t great anymore, it was a dysfunctional situation. It came to an ultimate head in Australia. The way that the whole thing has been presented to the world is that I kicked him out of the band. He had quit the band. He’s going to have his version of the story. I’m telling my version of the story. Is it even fair to anybody? There’s a rebuttal, “This is what happened.”

You ended up as the lead singer of Black Flag.

I didn’t. What happened is the whole thing melted down that night and the show ended. I sang a song after he had left the stage. A guy from another band came up and sang a song and then another person sang. It ended as a celebration of the music. It was a real positive ending to a bad situation. It wasn’t like I became a singer. After the show that night, Greg was like, “I’m done with this. I can’t. I’m over it. I don’t want to do this anymore. It’s a nightmare.”

A couple of months later, he called me and went, “I can’t let it end like that. Would you be willing to take on the role of singing?” By this point, he had brought me into his world. I had been such an integral part of everything he had been doing for years. We’re friends. I also watched what happened and I knew I could do it better. I’m not the same singer that Ron is. I might not sing the songs as good as him but I could pay tribute to this music and those songs with all of my heart and soul with a relationship with Greg that was positive.

We were in it together to present the music to the people and bring it to them. I thought I could do that job so I said yes. I’ve been the singer of the band since January 2014. We have toured pretty extensively but our best days are still ahead of us. We’re getting better at doing it and I’m getting better. I have an even greater understanding of the songs. These aren’t my songs. Most of them are associated with different singers with Henry Rollins, Dez Cadena, Keith Morris or Ron Reyes. There are four singers before me.

Most people only know Henry Rollins or Keith Morris but there are two other singers too, Ron and Dez. There have been a lot of singers that have been part of the history of the band. Although the songs are associated with those guys, they didn’t write the songs. Greg wrote them. They’re Greg’s songs, lyrics and music. He has determined that I’m the person to sing his songs. That’s where I come from. It’s like, “The man who wrote them wants me to sing them. No one else is going to do it. It’s going to be me. I’m going to do it.”

“Greg wrote them. They’re Greg’s songs. They’re his lyrics. It’s his music. And he has determined that I am the person to sing his songs.”

That becomes a drive and a purpose. That gets you up every day to honor that.

It has taken me quite a lot of time to process it in that way because there is so much noise. There are grumblings from the ex-members, online rants, an audience that has an opinion and the ultimate reality of how we’re in the room, van and on stage together. We know it’s good. We’re doing the best we can. People are leaving the shows having a good time. That’s all that matters. I have to put everything that comes with it aside and honor the relationship and the music.

The next event I saw is in 2023 for Black Flag.

We have a show booked in Jakarta, Indonesia but activities will start before that. We will probably be announcing shows in the US for 2022 relatively soon.

You also have The Complete Disaster tour. It’s the name of the group. It’s not that the tour is going to be a complete disaster.

The idea is that is it art unless it’s on the verge of becoming a complete disaster?

That’s for entrepreneurs. You talked about going all out. Give it everything you have. Every time you go out there and you give it everything you have, that’s where you live. We felt that way coming down here to do this activation for the show. The email I sent to my whole team involved was like, “Either this is going to be an amazing experience and we make all these partnerships and have great conversations or at the very worst we had a great weekend in Sunny Florida.”

That’s the way to do it. The Complete Disaster is the band we put together in Des Moines, Iowa. I’m very excited about the music. We released an EP. We started touring it in May 2022. We got tour dates in May 2022 and then the summer too. I’ll be pretty active in music. That will be good. I’m excited about the music. The way that audiences have been responding to The Complete Disaster has been great. I have another band Revolution Mother.

We have a show in June at the Born Free Motorcycle Show in Southern California, which is a huge show for us. That band hasn’t been active in many years but people in the motorcycle culture love the band. We’re getting together for that show. I’ve got three bands and I’m releasing another album sometime in 2022 with a buddy of mine, Matt Baxter. We have a band that we put together called The Morning Trail. I don’t know how to characterize the music.

It’s rock but it’s not as aggressive as The Complete Disaster, Black Flag or Revolution Mother. It’s a little bit different. We’re very excited about those songs too. I’ve got a lot going on musically. Some people think, “Focus on one thing.” You live one time and try to maximize it. If the well of inspiration is there, you tap into it. Don’t good things are coming in from all of those relationships. Musically, I’m happy about everything. If something was a stinker, I would shut it down.

“If the well of inspiration is there, you tap into it.”

What’s next for the business Street Plant Skateboarding?

One of the main reasons I’m here is we have a collaboration with GORUCK, which sounds bizarre but not to Jason and me. We connected in 2010. I did a GORUCK challenge. We have been friends ever since and stayed in touch. It’s very much like Greg. It was years and we have stayed in touch the whole time. We should do something together. We never figured out what that was. We’re activating that. We have a collaborative skateboard and rucksack coming out.