There are few certain things in life, but one of them is the fact that crisis will strike and we as leaders will have prepared ourselves and our organizations or we will fail in our response.

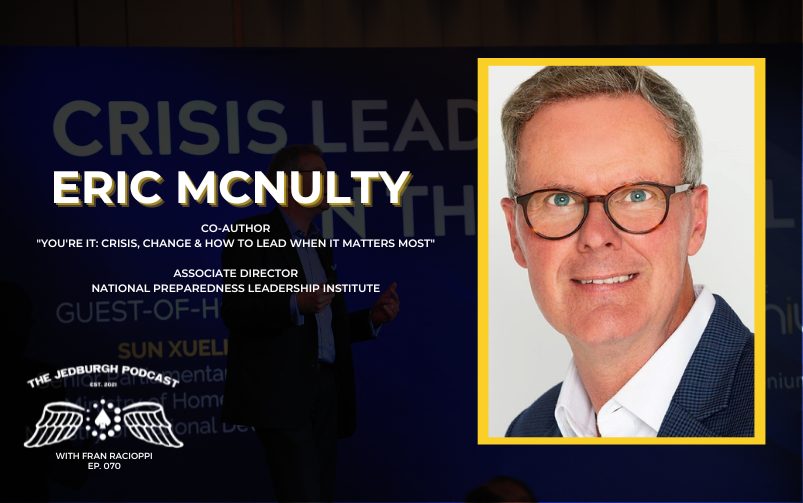

In this Boston-based episode, Fran Racioppi sits down with Eric McNulty, Co-Author of “You’re It: Crisis, Change and How to Lead When it Matters Most” and Associate Director of the National Preparedness Leadership Institute, to explain how success in crisis comes down to Meta-Leadership and our ability to lead down, up, across and beyond. Fran and Eric also discuss strategies to make sense of complexity, the perspective of the cone in the cube, knowns, forces, and a lightning round of crisis leadership do’s and don’ts.

Read Eric’s book, “You’re It: Crisis, Change and How To Lead When It Matters Most.” Find him on Twitter @richerearth & LinkedIn. Learn more about the National Preparedness Leadership Institute at Harvard at npli.sph.harvard.edu and on Twitter @harvardnpli.

Read the full episode transcription here and learn more on The Jedburgh Podcast Website. Check out our video versions on YouTube.

—

Eric wants to empower people on every tier of the organization to craft work experiences where their contributions matter and are recognized. Where people derive satisfaction and meaning through their efforts. These are organizations that appreciate both rebels and steady hands. Their leaders cultivate talent as the surest path to innovative ideas and satisfied customers. Armed with a better understanding of how our decisions in the workplace affect our coworkers and the world around us, we are unstoppable. And Go Red Sox!

Eric wants to empower people on every tier of the organization to craft work experiences where their contributions matter and are recognized. Where people derive satisfaction and meaning through their efforts. These are organizations that appreciate both rebels and steady hands. Their leaders cultivate talent as the surest path to innovative ideas and satisfied customers. Armed with a better understanding of how our decisions in the workplace affect our coworkers and the world around us, we are unstoppable. And Go Red Sox!

Tag, you’re it. That’s the game we used to play when we were kids. Some kids got tagged and pouted. Other kids got tagged and immediately went on the offensive. I would have never thought to compare our childhood pastime to solving adult problems until I read the book You’re It: Crisis, Change, and How to Lead When It Matters Most. Most often, in crisis management, like in tag, we are suddenly it when we least expect it and whether we like it or not.

There are a few certain things in life, but one of them is the fact that crisis will strike. We as leaders will have to prepare ourselves and our organizations or we will fail in our response. To unpack You’re It and learn more about what it takes to lead organizations and people in crisis, I tagged coauthor, Harvard instructor, and Associate Director of the National Preparedness Leadership Institute, Eric McNulty, to head East to Boston, Charles River and meet me at the Boston University DeWolfe Boathouse.

Eric explained how success in crisis comes down to Meta-Leadership and our ability to lead down, up, across, and beyond. We talked about making sense of complexity, the perspective of the cone in the cube, Knowns, and forces in the three dimensions of Meta-Leadership. Finally, I challenged Eric to a round of crisis leadership quick hits where the only right answer is a wicked one.

—

Welcome to the show.

Fran, thanks so much for having me.

Thank you for crossing the tracks and coming over from Harvard and MIT over to Boston University. It’s awesome that we’re here in the boathouse. We’re on the Charles River.

One of my favorite views of Boston is this side of the Charles going into town. You get to see the skyline. It’s terrific.

I gave you the view.

You gave me the view, which is nice.

I’m very excited and honored to have you here. You and I met. I read You’re It shortly after it came out, I read it. I was fascinated by what you and your coauthors had put together. I had not yet even conceived the show in full. I was still in this area where I said, “I want to do it. What would I talk about? Who would I talk to?” I read your book and said to myself, “These are people who I would want to talk to.” This resonated with me so much. It’s great to have you on because you have been on my list of potential guests for so long since we started it.

You are one of the foremost academic experts in crisis leadership negotiation and conflict management. You’re the Associate Director of the National Preparedness Leadership Institute. You partnered with Harvard on that. You’re the co-author of Crisis, Change, and How to Lead When It Matters Most. You advise federal states and local businesses in crisis management and crisis leadership. You sit on a number of boards, including the Crisis Response Journal and Massachusetts for Elephants. This is not the first episode where elephants have come up. We might need to circle back. Thank you for taking time out of your day to come down here.

It’s my pleasure. Thank you so much. I’m happy the book resonated with you because we wrote it to have a practical impact. This was not an academic exercise. The fact that it resonated with you means a lot to me.

The tagline of the show is, “How you prepare today determines success tomorrow.” In my experience reading the book, there’s only one thing we concretely know about crises. That is that it will strike. We may or may not have forewarning. We may or may not see it coming, but we have to be able to respond. We will have to take action as leaders. How well we act, take action, and lead and direct our teams will have a direct correlation to how well we prepared for that moment within ourselves, our teams, and our organizations. Crises will challenge every facet of our leadership.

Our success and failure will be dictated by the investment that we made in getting to that moment. You have put forth this concept of Meta-Leadership. It’s this idea, “In complex systems, a big part of leadership is the capacity to work well and help steer organizations beyond one’s immediate circle. You develop a 360-degree multidimensional perspective on the people around them and their relationship to other people.” We talk about implementing Meta-Leadership. Can you define it for yourself?

The reason we chose that meta prefix was you’ve got to take that broad view, see the whole situation, and look at the system. This is part of the complexity angle of things. Who are the stakeholders? What’s happening? It can be so easy. When a bad thing happens, our natural inclination is to get right into the weeds, “What has to be done right this second?”

“You can’t always prevent the initial incident…You can always prevent the secondary crisis of a fumbled response.”

That is important, but if you’re going to lead, you have to see what’s going to come next. That means picking your head up, looking around, and seeing what’s happening to that meta prefix, much as the way meta-analysis looks at a lot of studies and the throughline across a whole bunch of work. You want to see what is the bigger picture. What does this mean? How bad? How long? Who is involved?

You brought up the word crisis, which is so important because you can’t always prevent the initial incident like the earthquake, the hurricane, or the active shooter event. You can always prevent the secondary crisis of a fumbled response. That’s why the preparedness aspect you talked about is so important. Where we have seen organizations stumble is often in that response. They weren’t ready for it, so they made missteps, got behind the cycle, and had a hard time catching up.

[bctt tweet=”A big part of leadership is the capacity to work well and help steer organizations beyond one’s immediate circle.” username=”talentwargroup”]

That’s why when you’re thinking about it and taking that broad view, you want to see what’s on the horizon, “What should I be looking out for? What are we going to do, not in minute detail?” A lot of it is about principles, “What do we stand for? What are the basic things we have to do and get right no matter what happens?” Being able to do that at speed and scale is what makes the difference.

The book is called You’re It. I was catching up with Todd DeVoe, who was our mutual acquaintance. He hosted me on his show. The book came up and I asked him to introduce me to you. This concept of You’re It is where the leader finds themselves immediately, whether it’s by design, they’re in a position, or they get the adage of, “There I was minding my business. All of a sudden, here I am. The phone call rang, and now I’m it,” these events happen but this now tests these leaders.

You said, “Crisis leaders have to be psychologically and physically ready to act on a moment’s notice. You are the starting point for exploring and enhancing your capacity to lead. It’s important to be continually reflective and intentional about who you are, what you do, and how you do it. They count on you to have the confidence to respond effectively, keen awareness, and understanding of how your personal experiences, decisions, stumbles, and triumphs got you to where you are now each prepares you for the moment that you’re it.” What does it mean to be it?

You’re it when you are the person who has to take action, give direction, make a decision in a moment of crisis or high stress, be able to carry that, do it, and step into what needs to be done. You’re the one who can ground yourself emotionally and psychologically, see what’s happening, understand what you need to do, and then motivate people to do it. Here’s the reason we talk about intentionality. You came out of the military. The military trains leadership deep because you never know. When that Lieutenant, unfortunately, takes a bullet, who’s stepping up and being in command? Everybody has to be ready to step up if they’re called upon to do that.

You don’t even know you’re training it most of the time. It becomes part of it. It’s this succession of command, “The next man is up. Who’s up?”

You’ve got to be ready to do that. In the civilian world, we don’t do that nearly as well. We wait until somebody gets to a certain position. They say, “You’re in a leadership position. Let’s try and train you to be a leader.” It’s a little bit late. The same thing happens in some of the uniform services on the civilian side. They wait until you get to a certain rank. It’s like, “We’re going to try.” That’s a little bit late.

We’re talking about building muscle memory and mental capacity, but you have to own it yourself. You are it in terms of your development, whether that’s what you read, the podcasts you listen to, or the experiences you put yourself through. Get yourself ready because you don’t know. It could be something as simple as a car crash on the highway. You’ve got to get out and take action. If something happens to your family, you’ve got to step in. It could be one of these major corporate or public crises. We have talked about the major incidents where you have to step into the breach.

Sometimes we’re selected to be it. A lot of times, we’re not because we’re in a certain position. Other times, there is no leader when we look at certain crises. You’ve referenced in the book a number of these types of events. The people in charge and how they become in charge have varied widely. If you look at the Boston Marathon bombing, it was this concept of swarm leadership.

In Katrina, Admiral Thad Allen was the Commandant of the Coast Guard. This was right before his retirement. He was in a position where it made sense that he was going to take charge. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was a situation where you’re called in the night to come and figure this thing out. Can you talk about the differences in your personal circumstance when you become it and how that affects your psyche and those initial first stages? It is very different in each one of those how you assume this role.

One of the biggest differences we see is that the people who think they are it, once they get named to put in charge of something, “They put me in charge. I must know what I’m doing,” are the ones who get into trouble.

Why is that?

“I’m in charge. They picked me. I must be great.” We saw that in Katrina. I don’t want to name names. The head of FEMA was relieved of command and taken out of his job. Thad Allen stepped in. Nobody knew Allen at the time. He threw his Coast Guard experience. He had been preparing to lead. He had been in leadership roles. He knew how to step in, take command, and take the necessary steps. Often, people are going to get promoted either because of technical expertise or political appointees get put in because of political connections and assume they know it all now.

The thing I see as most consistently true in those who lead well is, first of all, they’re confident, but they’re humble. They’re continually trying to get better at what they do. We talk a lot about mastery. If you’re in a martial art or you’re a carpenter, you’re always striving for mastery. You know you’re never going to get there. You can always get better. You’re never at that point where, “I can’t screw this up. Whatever I say is going to be the right thing.”

It becomes arrogance.

Confidence breeds arrogance. There’s the famous phrase, “Failure is not an option.” I’ve heard a lot of people say, “Failure is not an option.” I hate to tell you, but failure is always an option. It may not be your preferred option and it’s not the one you’re shooting for, but things can go wrong. It’s important to keep that in your mind because you’re thinking, “If things don’t go as well as we think they’re going to, what are Plan B and Plan C? How are we going to adapt? What are we going to need?” That keeps you from moving too fast in the wrong direction.

“Failure is always an option. It may not be your preferred option… but things can go wrong.”

When you talk about stepping into these roles, Thad is a great example. He wasn’t the Commandant yet for Katrina, but he was you’re rising through the ranks. That was what brought him to the national stage. He didn’t have to go in and start telling people what to do. He knew how to step in and give permission for qualified people to do what they knew how to do and what they needed to do. He also expressed confidence in the public, “We know what we’re doing now. We’re going to take care of this.”

It helps that he was a Coast Guard. Coast Guards get a great reputation for doing that. When he got to the point of Deepwater Horizon when he was named the National Incident Commander, it was interesting. If you go read the statute, the Protection Act of 1980, what that National Incident Commander is supposed to do is three lines long. It has no authority. Thank goodness he was the Commandant of the Coast Guard. He had some resources. He could call them right away.

He knew how to inhabit that role, step in, and say, “I know what I’m doing. When I don’t know what I’m doing, I’m smart enough to find the experts who can tell me what we should be doing, listen to them, and even when you’re seeing a bad situation like Deepwater and Katrina, express that hope and confidence we’re going to get through it. We will make it right, take the right steps, and get through it in a way that you are aware of what that’s going to take.”

You brought up a couple of points there that I want to dig into a little bit more. Primarily, you brought up this concept of resource management and resource allocation. In a crisis, this is an important point. When the public looks at these things, they look at someone and they’re like, “This person is going to have all the answers.” I always want to look at that person in charge and say, “They have been put in this position due to their expertise.” The expectation is that they’re the person who is going to sit down, draft the plan, and figure it out when the reality is that the greatest leaders are the ones who understand resource management, resource allocation, and empowerment of the experts.

We talked about it in the military. The generals who read this will get mad at me, maybe. They’re all important, but the reality is it’s logistics because we can’t fight without logistics. We have seen this in Russia. If you can’t feed the tank machine, you’re stopped. In this example of Thad Allen, he’s not an expert in oil spills, but he can be put into that situation to then maneuver and resource allocate. He becomes wildly effective.

He knows who to call upon. Thad always talked about having a list in his pocket. He calls them dogs that hunt. When you’re hunting down South and you put the dogs in the truck, you want the dogs that can hunt, not the ones who are going to lie in the back of the truck waiting for you to get back and give them a treat.

My dog does. I live in the North.

You always want to know who you’re going to call upon to be on your team. If you are put in that position, you’re it, and you’ve got to pull together folks fast, then you want to get people who know what they’re talking about. They’re willing and able to make decisions. They know, in the case of a public sector leader, the ins and outs of the laws and regulations that are going to apply. You can work well together. That’s the team you want to bring together.

“You always want to know who you’re going to call upon to be on your team.”

Crisis leaders who get into trouble and who ultimately fail are those that put it all on themselves. Every decision has to go through them. They think they have to have all the answers and they think they have to understand everything when a large part of what you’re doing is making sure your team is functioning appropriately. They’ve got what they need. You’re giving them the space. They’ve got the resources to carry out what they know how to do.

You’re always doing a bit of managing or leading up to whoever you’re reporting to. They create that space where you can get your job done. They’re informed enough to feel comfortable but not in your shorts trying to manage what you’re doing, and then working with all the other stakeholders to make sure that those you need on your side are assets and allies working with you, informing you, and keeping them informed of what’s happening.

This notion of all the answers is the classic formula that comes out of public relations. Rich Besser, who was a former student and was head of the CDC during H1N1 was brilliant. You can go back and look at his press conferences during that crisis, especially the early ones. There was a clear formula, “Here’s what we know, here’s what we don’t know, and here’s what we’re trying to do to close the gap.”

That way, you set the expectation, “I don’t have all the answers. We’re asking questions. We know you’ve got questions too. We are being proactive and trying to solve this.” That buys you the space to be able to go out and continue to build your knowledge base to adapt as you need, make the adjustments you need to, and ultimately get to the place where you’ve solved the problem.

Humility is important. Humility and curiosity are two big ones. We have this concept of the nine characteristics that are used by Special Operations Command to recruit and assess talent. If you take these nine, you can apply them to any organization. It’s about character. Character, as you talk in the book, matters. Our nine are drive resiliency, adaptability, curiosity, humility, integrity, team ability, effective intelligence, and emotional strength. All of those have to work together in these times of crisis for the leader to be effective.

[bctt tweet=”With leadership, you’ve got to take that broad view. You’ve got to see the whole situation, and then you can look at the system.” username=”talentwargroup”]

You mentioned a couple in here. You also mentioned the Knowns and the Unknowns. I want to get into that here because you have two more of these Knowns. At the risk of confusing myself and all the readers, I’ll say that there’s this difference between these four types of Knowns. There are Known Knowns, Known Unknowns, Unknown Knowns, and Unknown Unknowns. Each of these requires a different response. Can you break those down?

It is a bit of a mind-bender until you get used to it. My apologies to Donald Rumsfeld, although it was the Unknown Knowns that got him and us into trouble in Iraq. The basic formula here is to break down what is known versus what can be known and be able to put things in buckets. It helps to organize your knowledge and what you’re trying to do. The Known Knowns are things you know. They’re verified evidence. Something has happened, and you can verify it. Therefore, it begins to build a base of understanding of what’s happening.

Typically, if you’re in emergency management or one of these professions where you face a crisis, are you prepared for it? Once you know some things, the Known Unknowns are going to pop right up, “I know what I don’t know.” There has been an explosion. I know there has been an explosion. I’m going to start asking questions, “Has anybody been killed? Is anybody injured? Do we know how much damage? Who’s on the scene?” With those Known Unknowns, you know which questions to ask and who to ask them.

Ninety-five percent of the incidents you face, you will solve in those two boxes. You start asking questions, you get the answers, and you fill enough the first box of Known Knowns. When you get into a complex situation, this is where it gets a little hinky. You get into these Unknown Knowns. Someone knows what’s going on, but you may not know who that is. You have to seek them out. It could be an expert or somebody with a different perspective.

For example, when you look at the Coronavirus, there were companies I talked to. If they didn’t already have a chief medical officer, they quickly contracted with someone who had infectious disease experience. They have a chief medical officer now. They thought, “We don’t even know the question to ask. Let’s go find somebody who knows more about this than we do.” When you go back to the invasion of Iraq, there was the assumption that the population would all meet us with cheers and flowers. It would all be great and easy.

I’ll tell you firsthand that wasn’t the case.

I know people who knew that region well who could tell you that wasn’t going to be the case. It was a bad assumption. You want to be thinking about who knows more about this than we do enough that they will know the questions to ask that we can never think of asking. The fourth one is the Unknown Unknowns. Those are the things that truly are unknowable. This is useful for two things.

One is if you’re trying to brainstorm to come up with scenarios to test your team and your plans. It’s something crazy. They could help you get into an imaginative space, but on a practical level, when there are parts of an incident that can’t be known, it can be reassuring to tell people, “We can’t know that.” A more deadly variant of the Coronavirus emerged this fall. We can’t know that.

Will the next round of vaccines protect against whatever variant emerges? We can’t know that. Here are the assumptions we’re making and the hypotheses we’re testing. You can do all that, particularly leading up to someone who isn’t in the nuts and bolts of what you’re doing in the response. They’re saying, “You have to tell me this. I’ve got to know that.” You say, “Ma’am, this is unknowable. We’re going to put it in that bucket. We may get the evidence as we go along that we can move it to a different box.”

I’ve heard from practitioners, particularly during the Coronavirus, that we began to push this out into the field. People have found it a useful way to organize knowledge, “Here’s what I know. Here’s what I know I don’t know. Here are the areas where we have to go figure out what we don’t know. Here’s the stuff we truly can’t know.” It became a helpful way of organizing their thinking and knowledge base in deploying resources appropriately.

Unknown Unknowns was helpful with elected officials who wanted more answers that couldn’t be gotten or sometimes with the public who are against, “Why you’re the experts. Why haven’t you solved this?” Here’s the thing we can’t know. That it helps frame a situation in a different way. You’re acquiring knowledge and deploying it in a systematic way. That helps you do well in crisis response.

You mentioned hope. Is hope a course of action?

Hope is not a course of action, but it’s an important thing to do. If you’re leading, part of what you’re doing is moving people into an uncertain future with hope and confidence. If you’re in a bad situation, you’ve got to tell people that it’s going to get better. It may not be perfect. There may be some parts of this we don’t like. It may not be an ideal outcome, but you’ve got to have their hope that you’re going to get through it and get to the other side. Otherwise, they will disengage and stop working. You will get lots of dysfunction on a team. You’ve got to give them hope that you’re going to get to the best possible place.

Hope is an emotional interaction with the event, but it is not a decision-making factor.

You have to balance hope with realism.

“You have to balance hope with realism.”

Jim Collins talked about the Stockdale Paradox. Part of why he was able to survive in a prison camp in North Vietnam for so long is he was brutally realistic that this sucked, “This is not a place I want to be. This is a horrible experience. I’ll be better off because of it. I will get through this and I’ll be better off because of it.” To your point, the prisoners who were hopeful didn’t last because they were disappointed over and over again. It’s that combination of being brutally honest about what’s happening. We’re confident we’re going to get through this. We have hope for the future. It will be better when we get there.

We spoke about being the singular point of an identifiable person in charge. I want to unpack this concept of swarm leadership that we mentioned. We’re in Boston. We’re sitting here in the heart of the city, but this was prevalent in the Boston Marathon bombing because you did your research and identified it in the book. You looked back on it and, as you conducted your interviews, identified that nobody could tell you who was in charge.

It was a real paradox because in every other incident we had studied, you could point to someone and say, “He or she was in charge.” There was an incident commander. In this case, incidents are moving very quickly. People weren’t quite sure what it was initially. Technically, Governor Patrick was in charge. He’s now my boss. He’s over at the Kennedy School. He said, “Watch what you say.” I liked the governor then and I like him a lot now.

One of the things he did was realize that he was not qualified to be, nor should he be the operational commander. He often would come into the operation center and say, “What do you need me to do? How can I be helpful?” He could communicate to the public or call the president. There were things he could do to help things along. He did that very well, but he didn’t try and run the state police. He had no jurisdiction over the FBI and other agencies that were involved. When they started working, it turned out that these people for the most part, knew each other well.

It’s the leaders of the different organizations.

It’s everything from law enforcement to EMS and the Boston Athletic Association.

In Boston, everybody knows each other.

Boston is a small town masquerading as a city. We also were at the end of ten years of a lot of people. Our mayor was in his fifth term. Governor Patrick was in his second term. Tim Alben, who was the head of the state police, had been with the governor Patrick all that time and so on down the line. They had worked together. Here in Boston, we have three major events every year that are run as planned disasters. It’s the 4th of July, the marathon, and then the first night of New Year’s Eve.

They’re running around on the surface, trying to make this a safe, secure, and pleasant event for everybody and a good time. In the background, they’re practicing, “How do we work together? What are our protocols?” They’re testing equipment. They test all kinds of things and run scenarios in the background to get better and smarter about working together. That sounds pretty logical. It wasn’t happening in a lot of other places.

It happened here primarily because they were up against the Democratic National Convention back in 2004. It was the first National Special Security Event or NSSE after 9/11. There was a lot of pressure and focus here. When they got around the table, they realized they weren’t ready for it. They hadn’t done enough training with each other in being able to be a little flexible on jurisdictional responsibilities and things to respond to events. They said, “We better figure it out.”

9/11 was chaotic in Boston too. I was in this building on 9/11. We practiced on Tuesday. We had early-morning practice. I went home and went back to my apartment in Austin. It’s a mile and a half up the road over here on Comm Ave. I took a nap, woke up half an hour later, and turned on the news. It had just happened. Throughout that whole day, I remember that Copley got evacuated and the different hotels there. The Westin and the Marriott got evacuated. There were all these threats. It was complete chaos in Boston.

It was chaos in a lot of places because people had conceptually thought about a terror attack. They hadn’t thought about one at that scale. It originated in Portland, Maine. They came through here. This is the last point of embarkation. It originated here. I was on the American flight the day before on 9/10. I was supposed to fly on 9/11. There was a bump because of the Jewish holidays that year. I’m not Jewish, but I was going to a meeting. The meeting got pushed by a day because of the Jewish holidays. I missed that by a day. That struck very close to my house.

I didn’t know that. What’s that emotion?

It is profound gratitude. It certainly has informed me of wanting to give back. Part of the passion I have for the NPLI and the teaching we do through our Exec Ed and other programs is giving back. I was not in this world. I was doing communication stuff at the time. I had the chance to come in and meet the people who do this work, like the military, civilians, and all the different agencies and organizations that are involved in keeping us safe and secure. I appreciate what they do and the dedication they show to it. Ever since that time, I have been profoundly grateful for that, appreciative of what can be done, and also a little intolerant to some of the theatrical stuff that doesn’t do anything, but you have to do some of that.

[bctt tweet=”Those who lead well are confident, but they’re humble. They’re continually trying to get better at what they do.” username=”talentwargroup”]

It isn’t my long legs that make me sit on the aisle of a plane. When I fly, I always fly in the aisle because if something happens, I’m going to be one of the people who stands up and tries to stop it after those brave people on the United Flight who tried to do something. That’s preparing for my you’re-it moment, which I hope never happens. When you get that close to it all ending unexpectedly on the most beautiful day dramatically, and you’re going on a business trip with no preparedness for it at all, it reframes how you think about your life and what you’re doing.

Going back to this concept of swarm leadership, there are some things that are required. You laid them out as unity of mission, generosity of spirit and action, staying in your lane, no ego-no blame, and trust-based relationships. You hit on the trust-based relationships and a bit on the unity of mission and the generosity of spirit and action. Talk for a second about staying in your lane and the no ego-no blame.

Let me step back a bit in that. One of the things we have seen since 9/11 certainly is a lot of attention to the structures around how we manage incidents. We’ve got ICS and NIMS in the US and other systems elsewhere. We have a formal management system with roles. You can plug people into them. Everybody knows what they’re doing. That’s great but what was not addressed nearly as well were the behavioral principles of how you want people to behave in those roles and with each other to perform at an optimal level. That’s what swarm gets at.

It’s the people, the unit, and the ambition. It’s people knowing where they’re going and being committed to accomplishing that larger goal. The staying in your lane piece is about being credible and reliable at what you do and having domain expertise so that people aren’t looking over saying, “Is Fran going to get that done? Maybe we should get over there and take that over.” Famously, at least in my world, you hear the FBI saying, “Push those state and local guys. We’re in charge. Get out of the way. Go make a sandwich.” They’re pushing people out of the way.

That can easily can happen when there are egos involved in jurisdictional stuff. We didn’t see that here. It was very much that people knew the state police were doing their job. The Boston Police had their job here in the city. The FBI was running the investigation. They had worked together so much. The people knew each other as part of those trust-based relationships. They trusted each other to get their jobs done. That relates then to the generosity of spirit and action.

When I trusted you to get your job done and you trust me, I can still say, “Are you okay? Do you need anything? What can we do? How can we help?” One of the big decisions had to be made right away after the bombings, “Do you keep the subways open or closed?” You’ve got a couple hundred thousand people down by the finish line at that point. Boston traffic and parking are crazy on the best of days. A lot of them took the T in or they got to hear some other way that wasn’t by private vehicle.

The T is the subway for anyone who’s not from Boston.

They had to say, “Is it open or closed?” Transportation is a traditional soft target. If you leave it open and there are bombs down there, you’re going to have a lot more fatalities. It’s going to be ugly.

If you close it, you’ve got everyone on the street.

You’ve got a soft target on the street. How are folks getting home? The dilemma was this. Ed Davis, the Commissioner of the Boston Police, said, “My guys are flat-out managing the crime scene. We can’t help. Our transit police force is quite small. We can’t back them up.” General Rice, who was the head of the National Guard, said, “I’ve got people here. They’re not armed, but they’re uniformed.”

“How about we put some guardsmen and guardswomen under the jurisdiction of the Boston Police? There are one police officer and three guardsmen or guardswomen. We will deploy them throughout the subway. At least we can check bags. They can provide security presence.” They took with the mayor and the governor because in no rule book or regulatory framework are you putting National Guard under the jurisdiction of a local police department. It doesn’t happen.

It never crossed my mind.

Mayors don’t like National Guard or their streets typically because they like their police to take care of things, but the mayor agreed, the governor, Ed Davis, and General Scott Rice agreed. That’s what happened. They were able to open the subways and get people out of here while providing security. That was at the generosity of spirit, being creative, and saying, “What’s the situation? What do you need? How can I help? We will bend the regs a bit. Nobody is going to get in trouble over this because we’re solving a problem.” That’s what we mean by that, but that can only happen when you trust people to do the job they’re supposed to do as well. This isn’t stepping on toes. This is offering assistance.

A crisis is rarely, if ever, linear. We could frame so many different crisis events as what we call a wicked problem, not wicked in terms of how we’re from Boston.

It’s wicked in terms of how there’s no clear answer.

Every answer that you have and every decision that you make are going to have some other reciprocal effect, both positive and negative. You have to decide which is the better course of action. You’ve talked about three basic concepts as being imperative to leading in a crisis. It’s systems, complexity, and adaptation. You’ve also talked about simplicity and the need to break down these problems into bite-sized chunks that have some clear direction and path to follow. Can you talk about the three concepts of systems, complexity, and adaptation? How do you break them down?

This is one of the places we see people get challenged. Talking about systems is understanding that there is a complex adaptive system. There are a lot of parts, interactions, and interdependencies. Some of them you see and know about. Sometimes you don’t see them and you don’t know about them. One of the characteristics of a complex adaptive system is that there’s not necessarily a direct correlation between cause and effect. If you’re in your car, which is a complicated but simple system, and you put your foot on the gas, you are going to accelerate because the gas goes in, the spark plugs fire, and all those things happen.

They’re a very linear function.

They’re going to fix the linear. That is not the way people work. When we have groups of people, they are much more dynamic and there are many more factors that come into play. This is part of that meta-view. When you have a systems perspective, you’re looking to say, “Where are my leverage points? What are the things I might be able to do?” It may be a relatively small adjustment that has a large impact. You’re always attentive to what are the relationships between the pieces.

If you can change the relationship, you can change the function of the system. This bleeds right into complexity. You can’t take those two apart. The complexity is that you don’t necessarily know what’s going to happen. You’re expecting why it may or may not happen. You need to be attentive to what does happen. That’s what we need to be able to sense, adapt, and respond to. I always say, “More hypotheses, fewer assumptions.”

You’re testing your assumptions and those hypotheses as you go through. You’re seeing what happens and adjusting your behavior accordingly. For the simplicity piece, people always think of simplicity as an antidote to complexity, but it’s not. Simplicity is an antidote to complications. When you’ve got a complicated system like distributing food to people who have been displaced in a hurricane, that’s complicated, but you do your planning. You can break it down, “How is the food getting here and from where? Where’s the plane landing? How are we going to inventory all that stuff?”

Making those systems as simple as possible is what you want to do. Get the complication out of the system. The complexity you have to embrace. Complexity is. Where you are getting to the complexity is, “Let’s figure out what the local population believes, what they eat, what their rituals are, and who are their elders and understand the culture of what’s going on.” You might show up with all your boxes of food, and they say, “We’re not touching that stuff. We’re not interested.”

All that hard work goes to waste. We see a lot of this in humanitarian response. It’s typically rampant when people who aren’t used to doing the humanitarian response show up. Open your ears and your heart and try to say, “What frequencies am I not hearing here? What are the dynamics between the people and the different agencies and organizations involved? What interventions might I make to get us where we need to be?” You’re not going to simplify that. You’re going to have to put a lot of work into it.

What happened here in Boston from 2004 until the bombings in 2013 was attending to those relationships and finding lots of ways to build trust, reliability, and credibility across jurisdictional or organizational boundaries. You had a very cohesive system here among the people who were involved in the marathon and other incidents. We have seen it in other places as well in subsequent events.

What happens if you think too linearly?

You wind up in a very frustrating place. One of the first things we try and teach leaders to do is understand when you’re facing a linear problem versus a complex problem. If you’re facing a linear problem, you want to think in a linear way. You can solve it that way. If you’re not that linear, it’s a shot in the dark. In that linear approach, you may get lucky. It may work.

You’re it. You have to go through your thought process, which we’re going to get into. How do you know if you’re in a complex problem or a linear problem?

The more that it involves people, particularly people who don’t know each other or are only working together, you’re going to have complexity because you’ve got different framing of the situation, beliefs, traditions and all kinds of things that make it harder to apply a linear solution. If you’re in the military, you’re with your unit, everybody knows each other well, and you’re aligned behind the army values, the Special Forces and these things, you know what to expect from each other.

[bctt tweet=”You can always get better. You’re never at that point where you can’t screw things up.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Those linear solutions go a lot smoother or you can sit down and say, “We don’t quite know what’s going on here. Let’s try and figure it out. Let’s try some new ideas.” That’s when you realize you’re in a situation of complexity. When you’re going into a place where you don’t know people or you don’t know all the factors around it, you should be thinking in complex terms. Let’s be attuned to the relationships between people in the organization, less about what they’re doing but why they’re doing it, what’s driving them, and what’s motivating them. Until you understand that, you will have a hard time making the what work the way you hope it will.

You said a couple of things here that are important. You said, “Complexity offers choice. Complexity is. Chaos is not bad by definition. It simply is.” Why is that?

This comes out of our understanding of the natural world. It’s when any natural system transitions from one steady state to another. Let’s say you’ve got a freshwater pond. The ocean breaches and becomes brackish. The plants and animals are going to change as you change from freshwater to saltwater. In between steady-state one and steady-state two, there’s always a period of chaos. That is the transition phase. We were steady. I keep going back to the Marathon bombing because we’re looking over at the site here in the distance. At 2:40 in the afternoon, there was a steady state.

A week later, there was a steady state in between. It was a bit nuts, but that chaos is to be expected. You can diminish the chaos, but you can’t make it go away. Chaos can be a great opportunity for learning. It can be a way for you to begin to see things you couldn’t ordinarily see when everything is running through a routine. One of the things we talk about in our programs is seeking order rather than control. When you try and control everything, you often create more chaos. I was in a room of 50 students. I said, “Who likes to be controlled?” Hands don’t go up.

“When you try and control everything you often actually create more chaos.”

They start looking the other way down at their shoes.

When I say, “Who likes order knowing what’s expected of you and you know what’s expected of others?” A lot of hands go up. In that chaotic situation, you’re thinking, “How can I instill some order here?” That may be as simple as restating values and saying, “We know why we’re here and what we’re trying to do. It’s creating a unity of mission. That begins to create an island of certainty.”

One of the big global companies I’ve worked with has a very strict set of protocols for every situation and any crisis they hit. They’re involved in a lot because they’re everywhere in the world. People, environment, and assets are your priorities. First, take care of people. Second, take care of environmental concerns. Lastly, worry about the business and our business assets.

Even when people are in situations, they have been in some pretty crazy ones where you couldn’t know the outcome, you didn’t necessarily cause it, and you didn’t have the resources to control what was going to happen next. When everyone knew what the priorities were, they could start making decisions and taking action. The company was going to back them up as long as they acted. It’s people, environment, and assets in that order. Chaos is a period of change.

You look at it as an opportunity to sometimes make the change you want to happen. You can learn a lot and test some of your core principles and values. That’s the good side of chaos. The way to tame it is not by trying to control it because you will make yourself crazy. You can’t control the weather, the bad guys, and the media, but you can begin to inject order into the system. It’s often reasserting those core principles and values that give people something to hold onto amidst the chaos. They can still be productive and move forward.

I would argue, too, that one of the most important ways to instill some order is to also understand others around you. You’ve talked in the book here about the forces. There are forces for you, forces against you, and then forces on the fence. Why is the understanding then of the stakeholders who are involved help to bring that order?

When you understand what people want out of a situation, what they expect, and what’s motivating them, then that helps you understand ways you can move them hopefully to the for-you camp or at worst, get them on the fence where they’re fairly neutral. That only comes with hard listening and talking to people to understand. One of my faculty colleagues is Peter Neffenger. He was the former head of TSA and the former Vice Commandant of the Coast Guard. He was the Deputy National Incident Commander during Deepwater Horizon. As head of the TSA, he got yelled at a lot.

It’s not just by the passengers.

It was a job where you get yelled at a lot. It’s like, “Peter, do you do this on purpose?” There are two things he said, which are valuable, about those situations. One is, “You’re often getting yelled at because of what you stand for, not because of who you are as a person.” You happen to have that uniform on or you’re in that position. Somebody is angry. They’re going to vent. It isn’t because Fran is a bad person. It’s like, “You’re the person responsible or in charge. I’m going to yell at you.”

The second thing, which is even more important, is, “Whenever someone is yelling at you, there’s a lot to learn.” Listen. Why are they yelling at you? Why are they upset? Are they afraid? If you set the wrong expectations, are they disappointed? Is there an external pressure that because you’re disappointing them, they will have to go disappoint their boss or their constituency, and then they will get yelled at? What’s driving them?

“Whenever someone is yelling at you, there’s a lot to learn.”

When you hear that, you begin to understand what is driving stakeholders. You can begin to figure it out, “How do I help satisfy those needs? What can we do to bring them together?” One of these stories in the book is when Peter was at TSA back in 2016. We had these horrible wait lines of security. We’re having them again now. We still have them. We were back in the four-hour category. Everyone thought it was TSA’s problem. They were getting yelled at, “Fix this.”

TSA realized they couldn’t solve that problem because it wasn’t their problem as one agency. It was the collective problem of the airport community because it turned out that TSA didn’t know exactly how many passengers were coming through any part of the airport at any one time. They couldn’t properly allocate their staffing to get people through. It was one of the problems. The airlines hadn’t been willing to share that because it was sensitive information. After some conversation, it got them to realize it. If you look at the flight schedules, you have enough information.

You can go on the website, see the seat maps, and figure out exactly how many people are coming. I’m sure there are analysts in those companies who are doing that all day long.

They began a daily phone call sharing that information at the top airports in the country, which then led TSA to better deploy its resources. That problem went away very quickly once they began sharing information. It’s understanding, “What’s a legitimate concern here? What’s perhaps an overblown concern on the competitive sensitivity of this information?” It’s getting them to work together rather than being in an adversarial relationship and making it our problem and our solution, “Let’s get this together.” It gave you the resources and leverage you needed to solve a problem. If they were just pointing at TSA, they were never going to solve that problem.

I’m reminded of the cone in the cube and the concept that you’ve put forth. I have a colleague of mine, a former Green Beret who now runs a company where he does leadership training and leadership development. His name is Chris Schmitt. He’s a great partner and leader. He talks about perspective all the time. In his work at Azimuth Consulting and Azimuth Leadership, perspective is a central tenet.

This concept of the cone in the cube, as you started to talk, comes down to how the way and the angle at which you view the problem shapes your perspective and then subsequently informs your biases. Can you talk about the cone in the cube? What is it? How does that shape the cognitive biases that then shape your opinions on certain matters?

It’s a simple representation of what you talked about. It is understanding perspective, yours and others. If you imagine a cube that’s opaque, inside is a cone. If I drill a hole in the top and look in, what am I going to see? I’m going to see a circle. If I drill a hole in the side and look in, what am I going to see? Is it a triangle? We have two distinct valid perspectives. Both are right and both are wrong. They’re right because you saw what you saw.

You looked in and saw a circle and a triangle, but they’re wrong because neither one saw the cone and you only get there by integrating those perspectives. When you’re leading, it’s important to understand that you have a perspective that has informed you. If I’m looking through People A at the top, seeing the circle, and I’ve got twenty years of experience doing that or I’ve written fifteen papers on that, I get invested in that view of the world. I’m emotional.

From confirmation bias or one of the more common cognitive biases, we tend to overvalue information that supports what we already believe. We discount that which may contradict it. I get passionate about it. That’s a circle in the cube. You have to understand that once you accept the fact that you can’t alone see everything from every perspective, that opens you to begin asking questions.

You get beyond that confirmation bias and the other biases that come from your direct experience and expertise. During COVID and other public health emergencies, we saw different epidemiologists looking at the same data and coming to different conclusions about how fast it’s going to spread and how deadly it’s going to be. We had lots of debates about when we close businesses and schools and wanting to leave them open, or masks on or masks off.

Nobody got it 100% right.

Nobody was ever going to get it right. This is back to, “Having hypotheses, not assumptions.” Take that multidimensional view, iterate your way forward, test things, and see. Masks are good in a lot of situations if they’re worn properly with the right material. If you’re doing that, you may not need to do some other things. It’s about ventilation.

There are all kinds of different factors there. It’s realizing that parents wanted their kids in schools for perfectly legitimate reasons. Businesses wanted to stay open for perfectly legitimate reasons. How do we work that series of trade-offs? In that situation, you’re in the land of bad choices because there’s no perfect choice. No one is ever going to get it perfect.

Here’s the best you can do, which we didn’t see a lot of through this under either administration. I’m not being political here. It’s saying, “We’re doing our best. We think this is going to work. Here’s how we’re going to know if it’s working or not. We’re prepared to adjust. If it’s not working, we’re going to adjust, try something else, and get the public used to the idea that we’re figuring this out as we go.” We don’t open the playbook and say, “Here’s the answer. Let’s follow ABC. We’re done.”

[bctt tweet=”Chaos can be an excellent learning opportunity. It can be a way to begin to see things you couldn’t ordinarily see when everything is just running for a routine.” username=”talentwargroup”]

There are three dimensions of Meta-Leadership. It’s the person, the situation, and the connectivity. If we start with the person, you’ve defined this as understanding who you are, your character, and your purpose. Through that conversation, you’ve introduced these concepts of freeze, flight, or fight. You also introduced this concept of the basement.

I like this because I was driving up here and having a conversation on the phone with my wife. We were talking about an issue with my daughter. I said, “Lily always goes into the basement.” My wife immediately said, “What book did you get that?” I said, “I got it from You’re It. I’m on the way to talk to him. I’m already using it.” This is an unimportant factor in crisis management.

I hadn’t heard it put like this. I’ll read a quote and then turn it over to you, “Never lead, negotiate, or make major life decisions when you’re in the basement. The speech or decision you make when you’re in the basement is the one that you will most likely regret. Remember, the problem is not in going to the basement. The problem is how deep you go, how long you’re there, and what you do while you’re in the basement.” What’s the basement? Why do we go there?

The basement is a phrase to describe that survival instinct we have whenever we’re faced with a threat. Some people call it the reptilian brain or the amygdala hijack. We happen to call it the basement. It’s a term we got from a colleague of ours, Isaac Ashkenazi in Israel. You’re faced with any threat. It can be your daughter’s misbehaving. Someone cuts you off on the highway. You hear gunshots or any number of things.

Your brain is hypersensitive to risk and reward, particularly risk, because your brain’s primary job is keeping you alive. If it senses a threat, it goes into this survival mode, which is freeze-flight-fight. It’s sequential. We all go there. It’s instinctual. It happens before you know it. You look at a rabbit out in the backyard. When it senses you’re there, what’s the first thing it does? It freezes because predators’ brains are very sensitive to motion.

If it freezes and the predator doesn’t see it, the predator is not going to catch it and eat it. If the predator sees it, the second smartest thing to do is run like crazy or flee. If you get caught, you fight. We have that in there. We all go there. It’s what we say. You can’t stop going there, but when you know how to get out, you can move from reacting to responding.

In the military, you’re trained extensively so that when you’re being fired upon, you don’t go into panic mode. You know what to do. You’ve got the training you rely upon. That’s the basic secret here. We don’t have to go into the military to get it. It’s knowing something. Once you can demonstrate some self-competence, take three deep breaths and count to ten.

My grandmother always said, “If you’re angry, count to ten before you say anything.” I didn’t know she was a neuroscientist. She was right. Go make a cup of coffee or whatever it is. When you can do something you know how to do, that tells your brain, “We no longer need to be in this survival mode anymore.” That turns off that amygdala response that had created the freeze-flight-fight and gets you back into what we call the routine circuits of your learned behaviors.

You can then go up into your prefrontal cortex, where you do your complex problem-solving. It’s your executive circuits. It’s the way our brains are wired. When you’re under threat, your brain wants to keep you alive. It’s how it’s going to react. I always think of it as rebooting a computer if we still do that. It resets things. 3D press works well for me. Some people want to counsel. I don’t care about your senior school fight song or whatever it is.

Do something you know how to do before you try and get in front of the media, direct your people, or whatever it happens to be. Do something you know how to do. It’s why checklists are so great. Things on the checklist may not be the perfect things to do, but they get you started doing something you know how to do and you’ve rehearsed and practiced.

You and I talked about that when we spoke. We often get into these worlds where we say, “We need to establish practices that teach us how to think versus tell us what to do because every situation is different.” Although every bombing, hurricane, or earthquake is not the same, generally, you could define a process in which you have to think through certain response protocols, but you can’t write a script that says, “This is how I respond to a hurricane.” Every time a hurricane happens, this is exactly what you do.

Those checklists are something we use extensively in the military. Look at pilots. The pilots get in. I was having this conversation with somebody because we were talking about the interoperability of teams. It was in this boathouse. One of the things that we talk about in athletics and when you build teams in athletics is the time spent together. What you will hear a lot of athletes talk about is, “We didn’t practice enough together. We didn’t have enough time together. We weren’t in the boat or on the court long enough together. We didn’t understand how each guy responds.”

Often what I’ll come back with is the greatest pilots in the world. We’re talking about Coast Guard pilots. We were fortunate enough to interview a while ago in Episode 17 General Clay Hutmacher, who commanded the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment. The greatest pilots in the world don’t fly together every day. They rotate crews like American Airlines. You’ve seen stories of potential air disasters averted all the time because they have a checklist that builds confidence and trust with the pilots sitting in the cockpit together. They know exactly how they get to that point and what the protocols are to get themselves out of it.

It’s very important to have that because you will go to that base. This light is flashing. Therefore, I know I hit this switch or I pull this back. That helps get you out of there. It’s important. The time together piece is important also. It’s not that you have to be Person A and Person B together all the time. In the aviation example you brought up, it used to be that the pilot was the king of the cockpit. Whatever the pilot said went. Back then, it was always guys.

There were a number of disasters they learned that could have been averted had the copilot or a member of the crew had the confidence to speak up and say, “You’re wrong.” The pilot has the humility to listen and say, “This isn’t quite right.” They have changed the culture now to make it not only acceptable but expected that you will listen to bad information.

Everyone is looking for anomalies and reporting them. When you take it seriously, and you are talking about a team throwing people together that haven’t spent a lot of time together, it’s knowing when people are behaving predictably according to the checklist and when something is not quite right. That’s where you put your attention, “Why is this not right?” You can fix it. You go on and get back on track.

We talked about this with Dawn Riley. She is the Executive Director of Oakcliff Sailing on Long Island. She’s probably one of if not the greatest female sailors ever. I asked her that question, “Sailing teaches you this great concept of when in charge, be in charge. When not in charge, follow and get out of the way.” You talk about this overall responsibility of the captain and the skipper, but she brought that up too. Everybody in the boat still has a responsibility for safety to avoid wrong decisions. There are protocols built in where even if you’re sitting up in the bow and the skipper says, “We’re going to do this,” you can yell back whatever command they have come up with that says no. They have to listen.

I’ve spent a lot of time in the water myself. It’s a great situation to think about because you have to have confidence in yourself and your craft and still realize that Mother Nature always bets last. You can have a quick storm or a change of wind.

Sailing will teach you that too.

I’ve done some ocean kayaking. Things can go wrong in a heartbeat. You have to be ready for that as well. It brings you that humility, too, “Let’s pay attention to what’s happening the way it’s supposed to and what’s not. Is that important or not?” Firefighters are also great at looking for those anomalies. If one is recognized, you’ve got to pay attention to it and do something about it.

Let’s talk about the second dimension of the situation. You said, “There are two sides to the situation. It’s what’s happening and what we do about it.” There are these concrete first two steps, “Get out of the basement and then discern what’s happening.” Why are these the first two steps?

If you don’t understand the problem, you’re not likely to apply the right solution. Often we can jump to what we think is happening, not what is happening, and therefore start going down the wrong pathway. This is why you went back to driving to the Knowns we talked about earlier. It’s so important. What do we know? How are we building that picture so that when we understand what’s happening, we therefore know what to do about it?

When the first explosion went off in the Boston Marathon, we heard pretty much from everybody we interviewed. They thought it was either a manhole explosion because we have been having problems with that here in the city or with a propane tank explosion because of all the vendors who are out on Marathon Day. It was the second explosion that then clicked to them, “This is bad. This is terrorism. This is something very different than that.”

It’s knowing what’s going on so that you apply it. This is why knowing how to think, not just knowing what to do, is so important, “How am I framing this problem? Am I seeing it as not much of a big deal? Therefore, I may be a little slow. I’m not going to worry about things too much. This is very serious. We’ve got to move fast.” It’s paying attention to those signals and having an idea of what they mean, “Do I know what questions I need to ask?”

A classic example is the first planes coming into Pearl Harbor back in the ’40s. It got us into World War II. Those initial spotters thought, “Those are our aircraft coming back from our reconnaissance mission or training mission.” They missed the clues or didn’t ask the right questions and said, “What if this is? Are we sure about that?” That lost valuable time and cost lives.

What does the POP-DOC Loop do for us?

If I didn’t bend your mind enough with driving to the Knowns, we’re going to deal with the POP-DOC Loop. This originated with the OODA Loop through John Boyd back in the Korean War, which is still used by trained pilots. It’s Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act. That’s a sequence you go through. When they were looking at why were US pilots outperforming their adversaries in dog fights, he came up with this thing. They were able to see faster, understand what it meant, and make a decision to take action.

The pilot that could do that would disrupt the cycle of the other pilot and, therefore, would have an advantage in combat. They still around the world use the OODA Loop as training for fighter pilots. When we started looking at this, we were very intrigued by that idea, but we realized that as complicated as a fighter cockpit is, it’s still not complex. There may be a lot of controls and you’re moving fast, but there are only certain things you can do.

[bctt tweet=”We tend to overvalue information that supports what we already believe and discount what may contradict it.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Leaders in a complex situation have many more stakeholders and dynamics to worry about. How can we expand that concept? We sat down with Dr. Srini Pillay, who is one of our neuroscience colleagues at the medical school, and began talking through this. He helped us see that there are six distinct cognitive processes in your brain. POP-DOC is how your brain works when everything is working well. We didn’t make this up. This isn’t a theory.

It starts with Perceive. We have perceived and wanted to be more active. Open your aperture wide and bring some data in, “What’s going on? What can I see as is happening?” You then orient as they did in the OODA Loop, looking for patterns. We, humans, make sense of the world through pattern-making, “Where’s the stimulus and response? Is it repeating or not?”

That’s how we make sense of the world around us. If an event is unfolding, you’re trying to figure out what is it, “What patterns do I see?” Patterns tend to repeat themselves. Once you begin to see the patterns, you begin to predict what’s likely to happen next. This is important because, as a leader, you want to be anticipating what you’re going to face, not just what you’re facing but what’s coming next.

It’s to respond versus react.

I can predict this is going to be a long incident. There’s going to be loss of life, or whatever the prediction happens to be. In an ideal world, you make multiple predictions to put some probability against them depending on how fast you are and how many resources you have, but that prediction then should tee up some decisions. When you see the graphic, the first three steps from the left-hand side of figure eight, Perceive, Orient, and Predict, are your thinking steps as you’re during your initial analysis.

You then cross over because if you’ve made a prediction, you now have to do something about that prediction. It tees up the decisions you’re going to have to make, “If we think this is going to happen, here are the resources we need to deploy. By then, we have to get permission from so-and-so or whatever it happens to be. Here are the decisions we’re going to need to make.” Once we have made the decisions, we’ve got to turn those into action. You’ve got to operationalize them.

If we have decided that we need 1,000 people down on the Gulf Coast to respond to this oil spill, we’ve got to start thinking, “Where are we going to get them? How are we going to transport them?” If you don’t make that connection, the decision is worthless. You’ve operationalized and turned it into action. The C in the POP-DOC is Communicate. Make sure everybody knows what’s going on, our mission, your part in the mission, what are you supposed to do, and those kinds of things.

“We humans make sense of the world through pattern making.”

Communicate animates a lot of this, but we couldn’t figure out a good way to do that. It’s the last step in the six. It’s a figure eight. Once you’ve done that, you go back around to perceive if our actions have the intended effect or not. If they did, we do more of that of if we have solved the problem, we move on to the next piece. If they didn’t, now is your time to adjust. How is the pattern shifted? What do we predict is going to happen next time?

People go through the POP-DOC Loop in a second or less in a situation they’re trained to face. You’re in the military. You’re in a combat zone. You hear gunfire and very quickly assess, “Is that us? Is it them? How close? What caliber?” You quickly figure that out and then what you’re going to do about it. In novel situations or if you’re fixing a corporate crisis of some sort, POP-DOC is a great way to orient the crisis team, “Let’s sit down.”

One of the companies I’ve worked with has a very strict process of writing this stuff down, “What do we know?” There’s our Perceive, “What do we think is happening here?” They begin to do their analysis and go through it, “Our prediction is this.” They write the decisions and these things down. The initial one may take them 45 minutes or an hour to go through, but they get everybody on the same page. They disperse, start making the decisions, take the actions, and come back.

It could be 1 hour or 2 hours, depending on the situation. A few hours later, they say, “Let’s reassess and go back out again.” It builds a rhythm into your response. As a leader, you’re creating some predictability in what you’re doing. This helps tame the chaos we talked about because you’ve got a stable process. It’s a linear process around that figure eight, but it helps you incorporate a lot of complexity because you’re always sensing what’s happening and what’s changing, “How do I need to adapt what I’m doing and not get stuck responding to what we thought was happening a day ago?”

The third dimension is connectivity. Connectivity is a core concept of the whole Meta-Leadership piece because it’s the ability to work with others. A crisis doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Nobody is facing a crisis and sitting there on their own. Understanding those key relationships, people’s brains, motivations, the interaction between, and the requirements they need to effectively do their job requires these four facets of connectivity leading down, up, across, and beyond. Can you talk about these four and why they’re so critical to the Meta-Leadership concept?

Connectivity is important. No complex crisis is solved by one person acting alone. You need others. One study showed that about 80%, if I recall correctly, of all the leadership literature talks about leading down. You’re the boss. You’re in charge.

“No complex crisis is solved by one person acting alone.”

One of my questions is this. Why do so many leaders only focus on down? You nailed it.

That’s what they teach you. We’re going to talk about leadership. You’re in charge. These are your men and women. Here we go. What do you do? It’s very important to understand that piece but that’s only part of how you lead. You also have to lead up to the person you’re accountable and responsible for. How do you help? Back to the cone on the cube, you’ve got a perspective on the situation and what’s happening.

Your boss, who may not be in the physical location or is in a different part of the organization, doesn’t have the same perspective that you do. How do you help that person understand the priorities they should be setting and maybe the resources they should be allocating? If you need them to do that, what are the decisions you need that person to make? You have to be able to influence them. You can’t tell them what to do.

You can tell your people what to do. It may not be the best way to lead, but you can do that. That’s what you’ve got to do about influence. That is a different way of thinking about leading. Across to your peers, this is others within your organization getting everyone working in synchrony. Every organization has got a certain level of dysfunction across the different organizational silos. Don’t blow up the silos. Connect them intelligently.

That peer-to-peer work of being trusted by them, trusting them, and being able to engage with them is critical to getting other parts of the organization involved when you need them to. Beyond that, your external stakeholders are part of that enterprise of the people we talked about before being for you, against you, or on the fence. How do you get them for yourself? You lead them well. That could be the general public. It may be the media or your investors. There’s a whole range of people.

You have no authority, but if you have the ability to influence and lead them to get them to be on your side, be it active or passive support, that’s a powerful tool in your arsenal to be able to deploy when you’re in a crisis situation. Be thinking about all four of those and seeing where o you have leverage, where you need leverage, and how you are going to be able to create that unity of mission. That’s so important for success.

Is there any one of these that becomes more important at certain times? I asked that question because I had a boss once. He was phenomenal. He was the Commander of the 10th Group by the name of George Thiebes. He’s out now. He was great and so effective at all of these things, but he always came with this concept, “You have to understand what your boss’s boss wants.” At first, especially as a young officer, you’re like, “What the hell is this guy talking about my boss’s boss? Who cares? I don’t even know what my boss wants.” He was very effective because he always came with that perspective. Why?

It’s great advice. When you’re trying to figure out why your boss is behaving a certain way, asking for certain things, or demanding certain things, that’s often because they’re thinking about what their boss wants and expects of them, “Is it answers? Is it results? Is this going to slow us down? Is this going to delay a product release or whatever that happens to be?” They’re worried about different things than you are.

If you can make your boss’s life easier, your boss, in turn, can make his or her boss’s life easier. Life gets easier for everybody. Bad stuff only slides downhill. It’s going to get to you eventually. Keeping that perspective is part of that cone in the cube, “I need to be worried about certain operational problems right here in front of me. I’ve got this mess to deal with. What’s the impact going to be on my boss and the boss’s boss?”

One of my favorite stories from the book is with Jimmy Dunne from Sandler O’Neill investment bank down in New York. We were talking to Jimmy. I was down there and interviewing him initially because they were very much affected by 9/11. That’s a long story in the book and a very powerful one. Afterward, he took me on a tour of the trading floor. If you’ve never seen an investment bank trading floor, it’s slightly organized chaos. Everyone has got multiple screens and phones. Stuff goes constantly.

There are hundreds of desks in a row.

They’re all trying to make money fast. The markets move like this. It’s never all going to go right. I said, “How do you manage this?” He said, “Rule number one, bad news finds me fast. I’ll never fire you for bringing me bad news, but I’ll fire you in a heartbeat if you try and cover it up and solve a problem yourself. Everything we do in this business is reputation. The faster we can solve a customer’s problem, the better our reputation is going to be.”

“If I can help you solve it, I need to know about it right away. I’ll never yell at you when you walk in and say, ‘I made a bad trade. This thing is going South,’ because if you bring me in, I can help you fix it. We’re all better off in the end.” He has modeled how he wants to be led up because his boss is the end customer. He was the managing director of the firm. He’s answering to the customers whose money they’re playing with.

In understanding what they’re looking for, he set the tone, “If something goes wrong, bring it to me right away. I’m not going to shoot the messenger. I might get a little angry for a minute, but I’m going to do it in the way we’re going to start solving problems.” Realizing the different pressures at different levels helps you save the boss from him or herself.

One of the things I teach people is that when you’re building that relationship with your boss and you’re working through various scenarios of what you may have to deal with, be it product failure, an active shooter, or whatever the scenario happens to be, what are the decisions that are going to have to be made? “Boss, which of the decisions do you want to make sure that you make?” “If we have to evacuate a plant, I want that one. If we’re negotiating over an employee who has been kidnapped, I’m going to make the final call about whether we’re going to pay the ransom or not.”

[bctt tweet=”No complex crisis is solved by one person acting alone. You need others.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Whatever the decision is the boss decides that he or she wants to own, that’s giving you some information, “Boss, what information are you going to need from me to make that decision?” You begin to build that relationship but are able to lead up because now you know that person wants that decision. Here’s what they’re going to want to know. You can be ready to provide as much as you do know. You’re leading them in a way that helps them do their job better.

You’re managing expectations. Many leaders fail to do that. They get into the role. All of a sudden, they have this expectation that everybody else knows what they want when the reality is they have to inform everybody what they generally have as their expectation. Where in these four facets does conflict occur most, in your opinion?

Conflict occurs everywhere. There’s a quote from a guy. He said, “Conflict is inevitable. Combat is optional.” Max Lucado is his name. Conflict is going to happen. Whenever two or more people are together, there’s potential conflict. We disagree about where to go for lunch. There are all kinds of stuff up to the serious things. Understanding conflict but managing it and resolving it is critical because conflict could be good or bad. We could get into a debate about what’s the best strategy. We’re putting a rowing team in a competition. What’s the best strategy for beating Princeton or whatever we happen to beat? You’re not going to beat Harvard, but you might Princeton.

We have goals. I stood on this dock and said to the team, “Do you see those guys?” I was referring to the Harvard guys. I said, “They think you’re a piece of shit. Go out there.”