The directive given to our Green Berets is to win by All Means Available. To do so, requires a combination of ingenuity, understanding the environment, a clear plan and precision execution.

Mike Vickers built a career on winning America’s shadow wars by All Means Available. Mike started his career as both a non-commissioned and commissioned officer Green Beret before becoming a Paramilitary Operations Officer at the Central Intelligence Agency. Mike later served as the Undersecretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict, as well as the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, where he served as the lead Intelligence official at the Pentagon.

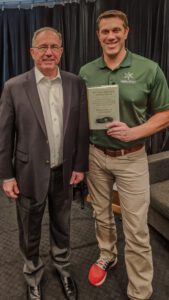

Secretary Vickers joined Fran Racioppi to chronicle his new book By All Means Available, Memoirs Of A Life in Intelligence, Special Operations and Strategy. He has been a part of almost every American known and unknown conflict for the past 50 years; including leading the defeat of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

We defined how America collects and uses intelligence in both national security and diplomacy. We discussed America’s will to win large conflicts, when we’ve gotten it right and why we get it wrong. And we went deep on the real enemy facing America today.

Mike sees the United States in a New Cold War that will challenge the nation like never before. He shares the reasons why America got here, and most importantly his Grand Strategy to rebuild a culture of winning global conflict to solidify America’s position as the dominant world power for decades to come.

Watch, listen or read our conversation from the Association of the United States Army as Secretary Vickers shares his leadership lessons learned through covert action; and don’t miss the rest of our AUSA series.

The Jedburgh Podcast is brought to you by University of Health & Performance, providing our Veterans world class education and training as fitness and nutrition entrepreneurs. Follow the Jedburgh Podcast and the Green Beret Foundation on social media. Listen on your favorite podcast platform, read on our website, and watch the full video version on YouTube as we show why America must continue to lead from the front, no matter the challenge.

—

—

Secretary Vickers, welcome to The Jedburgh Podcast.

It’s great to be here.

It’s been a while since we met. I told you this when I saw you. We met but you don’t remember because you were senior, and I was very junior. The story is I got dragged into the basement of the Pentagon by then Major General Jim Linder, who’s now a civilian like the rest of us.

I know Jim well.

When I was his aide, he said, “We got to go down there and see.” He would always talk about Mike Vickers. I’m like, “Who the hell is Mike Vickers?” We ended up in the basement of the Pentagon, the rooms that you see on TV that I didn’t even know existed. We sat and had a meeting with you.

I was in the back row, nondescript, and trying to stay awake. I know that you guys talked about some important stuff. Fast forward, whatever it’s been, we were at an event together in DC. You walked in the room, and I said to General Linder, who was there too, “We got to get him on the show.” You said, “I’ll be right back.”

Good to be here. What was General Linder’s job at the time?

He was the SOC Africa commander. We had come to DC. for a couple of days. He was making his rounds around the Pentagon advocating for the importance of Africa. He did a good job in doing that. I was reading the book, By All Means Available: Memoirs of a Life in Intelligence, Special Operations, and Strategy, this is the history of where America has been from a national defense standpoint for several years.

It was comprehensive. At moments, I would be like, “I even forgot about that. I didn’t even realize that happened.” The way you told the story was profound. You served as the Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence and the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict.

Also, interdependent capability. I had nuclear weapons, space, cyber, and lots of force transformation as well as SOF and CT. It’s a great job. No big deal.

You also served in the Central Intelligence Agency as a paramilitary operations officer. Most importantly, you were a Green Beret. First and foremost, you were a Green Beret both as a non-commissioned officer and as a commissioned officer. I’ll tell you, as myself or me like you, I’ll put it that way, we’re in Second Battalion 10th Special Forces, which I believe is the best battalion in all of the regiment. It was an honor to serve in the same regiment.

I remember when I went to Iraq in 2007 and visited the 10th Group and other units in Iraq. Our old battalion was ensconced in a palace. A guy who later retired as a major general but was my military assistant when I was Undersecretary for Intelligence. I was the battalion commander of Second Battalion. I thought, “When I was in Second Battalion, I never got to live in a palace.” They’ve got other things to do that are pretty important. People were shooting at them every day but that palace life was pretty good.

That palace, if I recall correctly, had a big crack down the center of it. I think we put some ordinance on that. We lived in it for a few weeks. Those were good times. I love that unit. I do believe still that 10th Group is one of those premier organizations within the regiment. They all do great things, but it’s certainly near and dear.

They all do great things. That’s certainly where I got my start.

We’re going to talk about intelligence. We’re going to talk about where we’ve come from, but in the context of where we need to go. We now are in dynamic times and in polarizing times. There are a lot of people who have a lot of ideas on where we need to go and what it needs to look like. We’ve gone through a massive transition and started, in many ways, a new chapter every time we get a new administration. It’s a new chapter in American history.

We’re embarking on a new chapter. There are a lot of decisions. There are a lot of things that have to get made. I want to start by defining intelligence. The Oxford Dictionary defines intelligence as the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills. It has a secondary definition, which is interesting. It says, “It’s the collection of information of military or political value.” I’d say you live certainly in that second definition.

In leadership, we use intelligence and information to make informed decisions as best as we can. Your entire career was based on the collection and analysis of intelligence to then make decisions, important decisions that would drive our country for decades. In your own words, what is intelligence? Why is it so important in national security?

That’s not a bad definition. It’s the tasking, and then determining your requirements, and then the collection. Some open, some clandestine, some technical, some human and then processing, in certain cases, if you need to analyze imagery, or break codes, or transcribe things. Analysis can be single-source or all-source. Disseminating that information to policymakers.

My experience was more on the collection and covert action side, clandestine collection and covert action, and overseeing most elements of the intelligence community in my last job. I was never formally an analyst, but I certainly benefited from analysis throughout my career. I worked with analysts closely. When I was a senior policymaker in the White House Situation Room, all our NSC meetings started with an intelligence briefing.

Our leaders use intelligence, and we have these intelligence capabilities that exist at various levels all across the world. Most people hear about them on TV. They hear about things like organizations or the Central Intelligence Agency, or we have the NSA or the FBI, which made a massive transformation over the years into an effective intelligence organization. Can you talk about the difference between a few of these organizations and how the Department of Defense structures and uses intelligence differently than the civilian-run organizations?

Our intelligence community has grown dramatically since it was founded after World War II with the Central Intelligence Agency. The only real independent major organization, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, is the other but it’s much smaller. It doesn’t have an operational role. Every military service has intelligence organizations. There are major independent organizations besides CIA, NSA, NGA, National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, National Reconnaissance Office, Defense Intelligence Agency, and then some that belong to other departments besides the Department of Defense.

You mentioned FBI. Also, DEA has an intelligence function. FBI is a large one. There’s one in state, in Energy, in Treasury, and a couple in Homeland Security. I don’t know if I’ve left anybody out, but it spans much of the government. You had a question about how DOD leaders use it. In some cases, it’s to inform policymakers, the chairman, the secretary of defense, people in the position that I held, and undersecretary for policy and others. It also informs our capabilities development over time.

The service secretaries and service chiefs are looking at foreign weapons and how to counter them. Our acquisition system, and our operating forces, the armed forces use it more, as you know very well from your own experience, for operational purposes like CIA and the FBI does. It’s a variety of uses. The one thing I would add to your definition, it’s not just military and political intelligence, but economic intelligence, scientific and technical intelligence that can make a big difference as well. The weapons cases that I talked about earlier.

I would throw in there even diplomatic efforts. One of the things that we have talked to a number of leaders when we talk about national security are the elements of national power. DIME, Diplomatic, Informational, Military, and Economic levers that our government pulls. What we come back to is, how do we know what to do across that spectrum? Many times, it comes down to the information that we have, the intelligence that we have.

That’s right. Intelligence is informing each of those areas of the DIME as well. For instance, cyber is a relatively new field. It has operational aspects and intelligence aspects as well.

We gave the highlights of your career, but it started when you were young with a desire to be an athlete. You had this individual, this teacher who came over to you and said, “You might want to go do something else.” Talk about what drove you to say, “I’m not going to be an athlete, at least at a professional level but this army thing looks pretty good.”

I was obsessed with sports. I was a quarterback in football and outfielder and pitcher in baseball. I was hoping I might have a career in those areas. In my senior year of high school, I was taking an international relations class. We were in the school library researching term papers and the teacher put a copy of that day’s New York Times on my desk in front of me. It was a big story about the CIA’s paramilitary operations in Laos with the Hmong people, the mountain people in the North of Laos and said, “You might be interested in this.” I thought, “Why do you say that?”

As I read it, I thought secret armies and this. I probably saw too many James Bond movies. I thought, “This is cool.” I wasn’t quite ready yet to give up on my sports career, so I went to college to try to continue it, both in football and baseball and it didn’t work out too well. I thought, “What am I going to do with my life since I’m not going to be a major college or professional athlete?” I started thinking about what that teacher had said and CIA. I had heard a lot about special forces and the Green Berets.

I started doing my research, and I thought this is a good path to go to immediately get adventure where an individual could make a big difference. Having qualified by taking the special forces selection battery and all the physical stuff you got to do and everything else, enlisted under the direct enlistment option. We call it now 18X-ray. That’s what I did in those days with the plan of serving in special forces, finishing my degree, and then going into the CIA. It worked out.

The rest is history on that. You tell the story. As I was reading it in the book as well, I think about when I was in college and I wanted to be a journalist. I went to Boston University. Tom Brokaw, Peter Jennings, and Dan Rather were the network news anchors. All I wanted to do was be the next one and then 9/11 was my junior year. I said, “What am I going to go do? Am I going to go into middle America somewhere and be a traffic reporter while I build my career?”

It’s because there’s these guys with beards and long hair riding horses through Afghanistan, in my opinion, saving the world and seeking vengeance on those who did us wrong. I said, “I got to go in the army.” That was the calling, and that call to do something meaningful and truly make a difference, I think, drives so many of us.

One of my connections to our efforts in Afghanistan in 2001, I had a few, but one that I still chuckle about is the summer before 9/11. We had taken our five daughters. We had taken the three oldest ones, who were not so old then, to a dude ranch for a horseback riding vacation. My wife was with the younger ones walking.

I took my then thirteen-year-old on the adult ride and galloping, and found myself on the side of a horse galloping down a trail where the latigo of the saddle had come loose. I had one foot in the stirrup, and I was on the side of this horse. I thought, “It’s going to buck in any minute. You better get ready to do a parachute landing fall.”

I did and everything. Fast forward, there’s these stories of Green Berets on horseback in the fall of 2001 and toppling the Taliban and Al Qaeda. My then eight-year-old daughter says to me, “Dad, it’s a good thing you’re not in special forces anymore. You would have fallen off the horse.”

Most likely, probably. It’s one of those things that everybody makes look easier than it is. It isn’t that easy.

I go back to Afghanistan to the ‘80s, and those wooden saddles and stuff aren’t for the faint of heart. They’re for real cowboys, let’s put it that way.

Let’s talk about Afghanistan for a second because the directive that you had in the ‘80s when you were running the covert mission on behalf of America in Afghanistan to arm the Mujahideen against the Soviets, it was the name of the book, By All Means Available. I think about when I read that, the Jedburgh’s of World War II, who were the predecessor to the Green Berets, the predecessor to the CIA, where they had to parachute behind enemy lines starting the night before D-Day in three-man teams with a very simple mission, win at all costs. Do whatever it takes. As you think about that definition, that term, by all means necessary, talk about what it means to you.

I tried to make it a theme of the book. The origins is Soviets invaded Afghanistan on Christmas Eve, 1979. President Carter, three days after that, issued what we call a lethal presidential finding to the CIA to supply weapons and other things to the Afghan resistance. Within ten days, the CIA had weapons in the hands of the Afghan resistance, and that started a very remarkable case of agility. For the first five years of the war, there was no thought that the Soviets could be driven out or the resistance could win. It was considered hopeless.

Resistance grew some and ended up being somewhat of a stalemate. I came in at the midway point of the war in 1984. At that point, a couple of things happened. One was a congressman from Texas, Charlie Wilson, who was on the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee of the Appropriations Committee in the House, had quadrupled the program budget. The budget went up from $120 million a year, the Saudis matched us dollar for dollar to $500 million.

I got the job just at that time to be the program officer for this covert action program. It became the largest covert action program in CIA’s history. We had an NSC review that looked at our objectives. One of them was stay the course, do other things, but variations on a theme. One of them was drive the Soviets out by all means available. I looked at that and thought, “That’s the one I want to do.”

Fortunately, I was able to persuade my superiors at the CIA, and they in turn, along with other top cabinet officials, Defense Secretary Weinberger and Secretary of State Schultz, went along with it as well. Reagan signed that. I remembered the phrase, “Drive them out by all means available.” It was in the working documents of the NSC. The final National Security Decision Directive, which I talk about in the book, doesn’t have those words. That was the top-secret code word. Now major portions of it are declassified and I cite it in my book.

It toned it down a bit, but that was our mission. Suddenly, it was to go for victory. What it meant in that immediate case for me was, how are we going to win now? Not just impose costs on the Soviets, but how are we going to win? I started transforming the program to enable the resistance to contest the Soviets in the air. The Soviets had complete air supremacy. We went from about 20 surface-to-air missiles to a couple thousand in a few annually in months.

To increase the combined arms sophistication of the resistance with all sorts of cruiser weapons and others, they were mostly a small-arms resistance up to that point at their training. Ammunition is what sustains operational tempo. If you want them to fight harder and more often, you have to have the logistical networks and spend a lot of money on ammunition. You see that in Ukraine now. We did that as well and then to take the fight into the urban areas.

The Soviets surged at the same time we did with their new leader Mikhail Gorbachev, at the time. Within twelve months, they were starting to look for an exit. We had won the battle of the surges. It stuck with me. It was the greatest job of a lifetime to fight our main enemy of the Cold War and to defeat them in the matter of a year plus, essentially. It took time for the agreement to withdraw.

I kept that idea in mind of when we are using. In military strategy, we talk about ends, ways, and means, the objectives we’re trying to accomplish, how we’re going to do it, and then what capabilities and resources we need. I’ve tried to apply that in the book to various things, when we used the appropriate ways and all the necessary means at our disposal to defeat our adversaries, and when we didn’t, and how this helps explain why we win in some cases and don’t win in others.

We think about the Soviet activity in Afghanistan. I think in a lot of ways, and as you referenced, that was not the only precursor to the fall of the Soviet Union, but it did have a big impact. It had a major impact. The eventual breaking up of the Soviet bloc and then the establishment of all these countries. Soviet aggression is something that we’ve seen throughout history.

We’re talking about it and you mentioned Ukraine. We had another leader in American military history, Colin Powell, and Colin Powell had the Powell Doctrine. It was this theory that America doesn’t want to go to war, but when America goes to war, we’re going to bring everything and we’re going to win. We’re going to win in a lot of ways by all means available.

If we think about some of the more recent conflicts, the conflict in Afghanistan over the last decade or so, I think in the early days we can argue and talk about we’re very successful. In the latter half, it became more challenging. The conflict in Iraq, which I want to ask you about, too. Do we still operate with this mindset of by all means available? Have we let policy or politics start to get in the way and cloud our judgment about when we as a country make the decision to go to war? Are we in it to win?

It’s a great question. The other side of the Powell Doctrine, which started with him and then Caspar Weinberger, Secretary of Defense, adopted it as well, is that you also ought to be clear about your objectives and then make sure you have what it takes to achieve those objectives. That’s the all means available. You saw that with desert storm. There was a real good alignment between the broad array of military capabilities, in both quantity and quality that we brought to bear with the objective of kicking Iraq out of Kuwait, which we did in short order and achieved our aims.

As you apply it across the spectrum of conflict, where you have lesser interests or where an insurgent has sanctuary, and for whatever reason, you’re not willing to invade that sanctuary. You still have the burden of being clear about your objective and, in my mind, designing a way to win. Whether you’re using just a few forces, some special forces to do something as we did in Colombia, or massive military force. You still ought to apply the same thought process but it is different and the timeframes can be different.

Part of the lessons for the irregular wars is that, as you said, Americans still think in terms of, we fight this to win it, and then we come home. It’s the World War II model or the Civil War model. Not all conflicts are aligned like that. As a strategist, you have to think about, “If this is going to be a protracted insurgency and our interests dictate that we fight this end or by, with, and through others, it’s going to take some time.”

If you overdo it, if you overreach strategically, when you mismatch those ends, ways, and means, then you can lose the political support that’s so essential in a democracy. That’s the burden for a strategist. The more you put in it, the more you better win, and win quickly. Whereas, again, if you think it’s a long war, you might want to think of your methods and how you have asymmetric advantage to win over time.

I think one of the biggest things that we would talk about as young officers, you would this rotation of forces. If you think about World War II, they loaded ships and went to Europe. “When are you coming home?” “When complete.” Yet, in our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, we rotate it every 6 or 12 months. The country had a strategy for better or worse and that evolved over time that said, “America’s going to remain here.”

At an individual level, you had a 6-month or a 12-month deployment. If you were in Ranger Battalion, you had a 90-day deployment. You had folks who served in Ranger Battalion who, at the end of twenty years, had 40 deployments. How does that affect how we fight these conflicts? You’re not fighting one war. You’re fighting 20 wars, 30 wars, or 40 wars.

At the extreme, this debate goes back to Vietnam, where it was said that the US didn’t have twelve years of experience. It had one year twelve times. I think it was John Paul Vann who said that. You need to balance expertise and keep people in the fight with the idea that if you’re going to fight for twenty years, they probably have to come home at some point. It’s not, land at D-Day and march to Berlin, and then you’re done a year or two later.

There’s probably a good balance depending on the specialty you have. You know, intelligence officers tend to need more time on the ground to do their work. As you said, some units, some SOF units, because they’re doing raids every night. Maybe 90 days is appropriate in these short cycles. You need some flexibility there. We probably aired too much often on the side of bringing people out.

Some of our most senior commanders tend to have slightly longer tours than the troops who are rotating, but not so much. What I like to think of as the World War II model was my friend, General Stan McChrystal, who commanded a unit for five years, essentially, and was in the fight like those World War II generals, stay there till you win it.

General McChrystal is a friend of the show. We had some great conversations with him. Let’s talk about strategy. You brought up strategy a couple of times, and you’ve brought up in the book this concept of having a grand strategy. In the beginning, we said America’s arguably challenged now like never before. Threats exist in every region of the world. As I was going through the book, and you’re going through this chronological history of conflict, you hit every continent.

If you take a step back and you think about what’s going on in that, you can spend years. People dedicate their lives to single regions of the world to understand conflict that then affects US national security policy. We have legacy foes like Russia, who we continuously seem to be at odds with over things. We have new radical organizations in terms of terrorist organizations. Some are operating even domestically as well as internationally.

We can talk for hours about how we got here with each one of these groups and what that journey looked like. We’ve lived it. We’ve lived a lot of that journey but I want to focus on where we go from here. We have a common friend, Mr. Jack Devine, who you served with in the agency and has been a mentor of mine as I met him in the private security sector. Jack always brings up this concept of what I call effective intelligence. You live this life, you have these experiences, and those experiences shape your mindset. They shape your decision-making.

Our past very much affects how we view the future, make decisions on the future, interpret what’s going on around us, and interpret the intelligence that we see for good and bad in a lot of different ways. You said that we’re in a new Cold War, and this new Cold War has three causes. I want to break them down, but I’ll put them out here in a second. Number one, a failure to fully integrate China and Russia into the American-led international order. Number two, significant changes in the balance of power. Number three, China and Russia’s perception that America is in terminal decline.

I want to talk about each one of these, but starting with the first one, a failure to fully integrate China and Russia into the American-led international order. Have we ignored the threat faced by Russia and China as America focused on the war on terror and counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency operations while we had near-peer countries who operated and were able to build capability while America was focused on something else?

This is a big topic, so if you’ll forgive me, and interrupt at any time you want, I’ll try to answer your question in all its complexity. The short answer to the end of your question is we probably neglected Russia’s revanchism. Its return to adversarial status more than we did the rise of China, but there’s some of that as well. Let me take a step back and talk about grand strategy just a bit, and then get to your specific points about those three causes of the new Cold War.

America became a global power in World War II, and it has been a global power ever since, despite the changing threat landscape. Some of the important lessons about grand strategy from World War II is, are you going to fight just Japan, or Japan, Germany, and Italy and all our foes? Hitler made it easy on us by declaring war on the United States the day after Pearl Harbor, but the US military had worked on many plans during the interwar years for how they would fight and if they had to fight them at the same time.

Out of that came this idea of Germany first, and then Japan. It ended up being a bit balanced, but that’s in the realm of grand strategy. Also, harnessing national power, mobilizing your society, and your economy for war. It got us out of the great depression. We won World War II for a variety of reasons, but one of the things I talk about in the book to outline what we do now is this idea of escalation dominance. Once the American economy got going, as Admiral Yamamoto said before Japan took over lots of East Asia, “Japan will win for six months, but once the sleeping giant wakes up, look out. They’re going to lose.”

That turned out to be true. We outproduced them dramatically in ships and everything else. We fought well, but we also had a big advantage in mobilization and logistics, and then a technological advantage in the end with the atomic bomb. That gave us that escalation dominance, both technologically and logistically. Famous British historian Sir Michael Howard talked about the other dimensions of strategy besides the operational, or technological, logistical, and social, and all of those who were in play in World War II.

I’ve lived through four national security eras in my lifetime, the Cold War, a brief period of unipolarity in the ‘90s when the US was essentially the sole dominant power in the international system, the Global War on Terror after 9/11, and now what I call and others call as well, this new Cold War with China and Russia. The US has been a global power all that time but again, with very different strategic landscapes. What you do globally against Al-Qaeda and its allies is very different than what you have to do against China and Russia. Also, the nature of the strategic competition is different.

For the first time in our history, in China, we have a country that has 70% of the GDP that we do. It’s not per capita GDP. We have never faced a rival like that. In the 20th century, we never had an adversary, Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, etc., who had more than 50% of our GDP. This form of economic escalation dominance that we had, if we ever got into a protracted war, we have less of now. We also have a new technological arms race in artificial intelligence.

It’s in the news about DeepSeek, a new and much cheaper Chinese AI program. It’s disrupting our stock markets, but also potentially our technological advantage in certain cases. I don’t think that will pan out. In quantum computing and in synthetic biology, these are such big technologies. They will affect economic power as well as military power or national security power.

It’s important that you win that race like we did in tech races in the Cold War. We face two allies with other allies who seem to be joining in with them. For the first time in a long time, we have China and Russia roughly aligned and best friends forever, as they say, then North Korea and Iran joining the party to some extent.

That’s newer in this period. All those things pose challenges for grand strategy. The difference between World War II and now, it’s why it’s more like the original Cold War, is that we change governments every 4 years or every 8 years at the most, according to our Constitution. Grand strategy operates in the realm when you’re trying to build your power relative to others and use your power wisely. Over decades, it has a longer time horizon than a big war typically or others. It’s more of a challenge for a democracy to have continuity in those areas.

We’ve seen that in our recent history, agreement on some broad principles, but big differences and bigger differences in some cases than the original Cold War. I hope we find that bipartisan consensus. Finally, to your point about the causes of this new Cold War, one of the patterns of history is that after one great era of competition comes to an end. When the Soviet Union dissolved, China was our ally for the last decade plus of the Cold War. I went to China many times in the ‘80s as a CIA officer. We cooperated on Afghanistan.

The Soviets were our enemy. The Soviets and Chinese had fought a border skirmish in 1969. After the Cold War, they realized that now the two powers potentially, in the future. This was the time of Japan as number one, but it was China and the United States. They certainly thought that way. Deng Xiaoping’s reforms had been underway for some time. The Chinese were the best students of all on Desert Storm. You looked at this phenomenal victory, and a lot of foreign militaries analyzed it, and the precision weapons of the United States, and the Russians applied it against their literature of reconnaissance strike complex.

The Chinese said, “What a dumb idea to allow the United States six months to build up massive force on your border. Don’t let them do that.” That became the origins of the anti-access aerial denial strategy, which is to try to keep US power projection out of the region, or make it very costly if they come in. They start targeting air bases and then surface ships and all the things we typically do to project power. As China grew more powerful, they became a bit more assertive and that certainly culminated with Xi.

I like to say that one of the first signals of this new world that we were in came in 2007, when China did an ASAT test to blow up one of its satellites. Vladimir Putin gave this crazy speech at the Munich Security Conference that said the US is an enemy and pushing its weight around the world, and we have to contest it. In 2012, that accelerated as Putin returned to power and Xi came back. I don’t think it was ever possible to integrate them into the international system. We tried.

You could say we didn’t try hard enough or something. I don’t think it was possible. Our strategy with China was to invest in them, while still hedging, to engage and hedge. It didn’t work. By 2018, in a bipartisan basis, we realized that our strategy hadn’t fully worked with China. With Russia, as they became more powerful in the first decade of the 21st century, but as Putin became more belligerent, it just didn’t work there either.

If you think about Tucker Carlson’s interview with Putin, and you take at face value what Putin said. We’re also talking about a career spy and master manipulator in Putin, but he blames the US and says, “We, as Russia, wanted to be part of NATO. We wanted to be part of the international order. You left us. You’ve created this mess.”

He says that there were discussions about, could you extend NATO to Russia at one point, and Ukraine, Georgia, and others. I think the NATO part has been overdone about Ukraine because that wasn’t going to happen for God knows when. The Germans opposed it, and everything else. I think it was a convenient pretext to first invade in a smaller way in 2014 and then annex Crimea, and in a much bigger way in 2022.

He also felt that the US had meddled in his re-election coming back to power in 2012. He had it in for Hillary Clinton. He wanted to destroy her. That was the origin of his intervention in the presidential election in 2016. It was to trash Clinton. He thought she would win, but he wanted to trash her. When he saw it was possible for President Trump to win, then he started backing Trump as well.

The second cause you lay out is the balance of power, significant changes in the balance of power. Before you talk about the changes, let’s define power. There are different interpretations. You mentioned President Trump. He’s front and center now as his second Trump administration has come into power. In a lot of ways, it’s very different than President Biden’s perspective on the world order and what American power is.

We’ve had an opportunity on this show to spend a good amount of time on Capitol Hill sitting down with elected leaders, and elected leaders will give you their interpretation of American power. What we hear from many of them in the new administration is strength is power. How do you define American power?

It’s multifaceted because there’s economic strength, military strength, intelligence strength, political strength, and the power of your ideals in array. You try to aggregate that. As the Chinese talk about, get a sense of comprehensive national power. Some of it takes place over time. It’s not something you can use now. If you’re perceived as on the side of liberty and freedom, that may prove decisive someday, influence in the world, but you don’t necessarily know when. It may not be now when you need it.

That’s why military power becomes, at the end of the day, the coin of the realm with intelligence power. Talk about technological power as well. What’s happened in the change of the balance of power? As they said China’s economy has grown very dramatically. They’ve got a lot more resources, including for protracted warfare. They can outproduce us now in ships. It doesn’t mean their ships are better, but they can produce more of them.

In general, the state is just richer, and they’ve extended their influence around the world. They’re doing reasonably well in the Global South. With Russia and them, they’ve made some gains in various areas. One of the biggest changes is in the military area. In their region, they have made it more difficult and risky for us to project power. Particularly in the old legacy ways. Bringing forces right on an adversary’s doorstep to bases nearby or offshore naval waters. They’ve made it far more difficult.

Essentially, they have demasked the United States to some extent in the way we traditionally project power. That doesn’t mean we can’t change and counter those things in various ways, but we’ve been a little slow to do that. They’ve become a pretty big space power in the last decade or so, and a cyber power as well. The new domains of war. That’s what’s caused the change in the balance of power and made it riskier, and why I think we need to address it.

With Russia, they’re not a continental-wide threat like they were in the Cold War, or a global threat in certain areas. It’s more countries on the periphery like we see with Ukraine now, but Georgia and the Baltics and maybe some others as well. They’re a threat to NATO’s Eastern flank. Not so much all of NATO, but they’re still serious.

They project power in other ways, through covert action, influence, assassinations, and a number of things that they’re doing. It’s less favorable. On the other hand, that could change. For instance, the assessment in the late 1970s, the Soviets were pulling ahead of us, and a decade later, they were gone. We got more aggressive in the 1980s.

You leave out Iran from this conversation about the balance of power. Why?

I don’t leave them out. It’s just that North Korea and Iran are regional powers with interests in the region and some global capability, but limited. China’s the big dog. Russia is the most acute threat now, the most aggressive threat. Iran had been on a roll with the so-called proxies and Shia crescent, but it’s suffered setbacks in terms of decimation of Hezbollah, its main proxy, but also its loss of Syria. It lost territory that it could try and ship weapons through.

Its air defenses have been weakened, and then Hamas as well. Iran’s not to be taken too lightly and North Korea. They can cause headaches. One of the challenges you have to deal with in broad strategy, and applies now as it did in the past, is you don’t want to overdo lesser threats. It doesn’t mean they’re not threats, but you have to have it in balance. There’s a famous phrase, “You have to keep the main thing the main thing.”

When we took on the Soviets in Afghanistan, if we won, it would have far greater geopolitical consequences. It was the only defeat the Red Army ever suffered in its history. Whereas, if we won in Nicaragua against the Sandinistas. It’s moving a piece on the chessboard, but it’s not going to affect the global balance of power in the same way.

I think for the past decade plus, to your earlier observation. Not only did we rightly focus on Al-Qaeda and those responsible for 9/11 and its allies, but we overdid for a while the Iran and North Korea threats. It doesn’t mean they’re not threats, but relative to China and Russia, who are more serious threats.

Does the proliferation of nuclear weapons for Iran and North Korea change that?

North Korea has become a nuclear power, and it’s a question of how many and how capable their delivery systems are, and their reach. Iran has always had a strategy of having a threshold capability, having a weapons design, the ability to mate it to a delivery system, and having fissile material that it could become nuclear if it wanted to, but it hasn’t wanted to cross that threshold.

Not even stockpiling since the JCPOA, the Comprehensive Plan of Action, but essentially, the Iran nuclear deal. The US withdrew from in President Trump’s first term. Through President Biden’s term, they’ve been stockpiling more material for weapons, but they’re still at that threshold state. Nuclear weapons changed the calculus strategically, and that’s why states pursue them.

The third piece that you have here is China’s and Russia’s perception that America is in terminal decline. I think it’s important to define what you mean by terminal decline, but I’ll also ask you. Do you think that our national security strategy has got soft? That’s why they think that.

Part of it is a bit of ideology. The Soviets believe that through Marxist-Leninism, that history was on their side. That history has to unfold in a certain way. If you wait long enough, the world will be theirs. Al-Qaeda and the global jihadists believe that for different reasons. Not Marxist-Leninism, but that may take a lot of time, but things are going their way.

One of the things that unites all our adversaries, China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, and the global jihadists is that they all think the US is weak and that it is in decline. That doesn’t mean they’re right. That doesn’t mean it’s an objective view of reality, but they act on that. Sometimes, again, it can induce some caution that we don’t want to be too reckless and peak too soon because things are going our way.

Al-Qaeda, for instance, Bin Laden and his ilk looked at our withdrawal from Lebanon in the ‘80s and Somalia in the ‘90s and thought, “You hit these people hard enough and they’ll leave.” It turned out to be a big miscalculation on his part but they do believe that. Part of it, it’s not purely military. Some emphasize the cultural dimension that we’re like some views of ancient Rome, that we’ve become dissipated, or that we’re divided, that we’re polarized and we can’t bring together all our power.

We’ll inevitably become more isolationist. They have a lot of reasons for trying to make rationales for making this calculation. Again, I want to emphasize, it doesn’t mean it’s right. If you assess I think somewhat objectively, US hard power and some elements of soft power against adversaries, we still look pretty darn good. What the national will is, some of these intangible factors, that’s tougher to assess.

I think that brings up two points. I’m glad you brought up national will. One of the things you talked about is mobilization a while ago. You said we’ve been successful in conflict where you’ve had national unity and mobilization. People will say, “We were at war for twenty years.” I’ll say, “Were we? Were we all at war for twenty years, or was 3% of our population at war for twenty years?” It wasn’t a World War II. We’re not making cars anymore. We’re making airplanes.

A third example of that besides the protracted wars against the global jihadists, is the war in Ukraine. You look at it and you think, we have a clear aggressor. This is in the US interest to see them defeated in Ukraine’s territory and sovereignty remain intact. Yet the arsenal of democracy of World War II can’t seem to outproduce in weapons, the Russian Federation and its allies.

How can that be when our economies are so much bigger? It’s because we can’t mobilize, and for a variety of reasons in the way we have in the past. Even for a shorter war and a war that no American troops are dying and other people are doing the dying and our job is to provide weapons. It is a very strong, if not vital interest of the United States. We can’t mobilize.

How do you change that? It is because you say in the book, you talk about how this political infighting can very well be detrimental to the national security strategies. What do you do?

I think it’s core. I know a number of my former colleagues, my four-star colleagues and others think the same way. That’s why when I talked about strategy going forward at the end of the book, restoring the domestic bases of our power. We don’t have to have perfect unity, but we ought to have unity on the fundamental things. If grand strategy is going to work in a long-term competition, some coherence and strategy like we did in the first Cold War.

In a time of disruptive economic change, that’s challenging. It is because people get disgruntled when they’re left behind, there are big political problems. I’m waiting for the political leader who can unify the country and get us on the same page. I don’t know what it’s going to take to produce that. If we can solve that problem, that we can restore the domestic bases of our power, and it’s a combination of economic power, national will, technology leadership and others. We’ll win the new Cold War.

We’ll deal with, where I spent my life, on the external national security threats. I’m not a politician, so I can’t tell you, “I’m the guy to do that.” I’m not. We’re clearly waiting for that person or persons. Again, proximity matters for that kind of thing. That’s a very nightmare scenario, but proximity matters there too. It’s just a horrible strategic decision to abandon that. It took us 45 years to defeat, more or less, the insurgency in Colombia. We did that with a small footprint the whole time, but should we have quit at the twenty-year point? That wasn’t going so well then.

Is Pakistan a friend or a foe?

We don’t have to have perfect unity, but we ought to have unity on the fundamental things.

I call them a frenemy. They were an ally in the 1980s, but they were a bit of a difficult one. When our interests are very aligned, they’re very important. The dilemma we had in years was they were helpful on Al-Qaeda, better to engage with them, giving the nuclear weapons, and supporting an insurgency that was killing Americans in Afghanistan. We never, across two administrations that I served in at a high level, were able to deal with that problem.

What’s your perspective on the media’s involvement in this disunity? If we’re going to bring people together, there’s got to be messaging behind that. It’s got to start with a will, but we see so much in the media in this divide.

I think it starts with political leadership, both in the Congress and in the presidency to rally the country behind a fairly unified purpose, whether it’s domestic and foreign or both, and most likely both, and has to begin there. The information environment is increasingly important. When the media turns against you, you’ve got a problem. As happened now again, you put yourself in bad situations. They’re trying to report things as best they can, but as happened after Tet in Vietnam in 1968, famously Walter Cronkite. Information is so siloed. People don’t get information from major sources.

We don’t even have the same information that we can argue about. One of the things I like to say too about domestic unity or polarization is, you can be very passionate about beliefs and we can disagree on a number of things. When you think your biggest enemy is another American or group of Americans, something’s wrong. That’s not going to end well no matter who wins. When you got people who hate each other, you get civil war.

The second element that you have is posturing ourselves to prevail in the race for economic and technological supremacy. Are we losing the tech and economic war to China?

No, I think China stumbled economically after four great decades of growth, and they’re doing well in certain economic areas. I think the US still has the advantage. The challenge is maintaining it. One of the tensions as the national debt grows but budget deficits grow would be to shift more resources into domestic entitlement programs. Therefore, not invest in the future. It’s like current consumption versus investment. You could lose the tech arms race.

A lot of it is in the private sector. It may be that not overregulating is what the government can do, or not breaking up certain companies that might seem good if you had just a domestic economy. When you look at it, you’ve got big international competitors in these big challenges. We wouldn’t have broken up the Manhattan Project for more competitive economic competition.

You want to get that thing before your enemies do, or it’s going to be horrible consequences. That, to me, is the central competition. If you look back 30 years from now and ask, “Who’s the leading power in the world with the most influence maybe has won limited wars?” It will be the country that is the most economically powerful, but particularly technologically that wins that arms race.

Were we behind?

There are certain areas where I think maybe we’re behind, but I don’t think there’s any particular one. The Chinese have an advantage for national security in terms of the civil-military fusion of taking data from private companies and then using it for national security capabilities. For instance, Beijing Genomics has the largest genetic database in the world. The more you understand about synthetic biology as manipulating biology for some other purpose. That confers some advantage. They’ve done well in quantum computing in certain areas.

I still think we have the advantage in all three, and in nuclear fusion and some of the other big technologies of the future. We’re at risk in terms of supply chain vulnerability and in terms of critical minerals processing. Not so much the minerals themselves, but the ability to turn them into something useful with the processing part. Things like batteries for electric vehicles, but it’s not insurmountable. The US position is still strongest technologically. You don’t want to lose it. That’s the big thing.

The third element is winning the intelligence and covert action wars. Covert action is this balance between diplomacy and military force. We’re hearing a lot specifically about the designation of organizations as terrorist organizations. The Houthis are back on the list after the Trump administration has come in. His now designated and looking at designating cartels as terrorist organizations, which then allows us and allows for and the use military assets at times but his isn’t a new concept.

Covert action is something that we’ve been involved and you’ve been involved in your whole career. It’s been incredibly important. You mentioned Colombia. Delta Force killed Pablo Escobar. This isn’t a new concept to leveraging covert action and going out to achieve national security aims. Why do we have to stay at it and possibly expand?

First, if the Soviet-American Cold War is any guide, we call it a Cold War, but another term for it is Hot Peace. A lot of people died in conflict during the Cold War. Its distinguishing characteristic is that it was indirect. The two superpowers didn’t fight each other directly. In Korea, we were directly engaged against the North Koreans and the Chinese. The Soviets are helping out a little bit with fighters, other pilots, and things but basically just helping supply. The same thing in Vietnam.

In Ukraine, we’re the supplier and they’re directly engaged. That’s a fairly typical pattern. Covert action is taking diplomacy, information operations, paramilitary operations, sabotage, and others and having it be done under Title 50 or covert means by the Central Intelligence Agency. That can include counter-narcotics, counter-terrorism, and all kinds of missions as well.

Designating, for instance, a cartel as a terrorist organization, or the Houthis, I don’t think changes much in the sense that you have the right of self-defense. If the Houthis are attacking you, you have the right to shoot back. You don’t have to designate them something to shoot back at them. If you wanted to invade them and they weren’t shooting at you, you have some legal challenges to get over. It’s the same thing with terrorism. You can do that covertly or overtly.

If you wanted to use overt military force, you need to make sure that you’ve got the proper justifications for doing that. There are a lot of laws. I’m not an attorney, but international and domestic as well, war powers, and others. You can take military capabilities and detail them to the CIA. There’s a lot of flexibility for presidents to get at things. I don’t think these things are necessary. Are the cartels very bad and are they killing lots of Americans? Yes, they are.

I had a chance to sit down with the former Boeing chief security officer, Dave Komendat, not too long ago. We had a lengthy discussion about not only aviation security but denial-of-service attacks. Where do denial-of-service attacks fall into this?

It’s the ongoing cyber competition. Cyber is this unique weapon that’s used for espionage. It’s a very powerful collection tool. The Chinese have stolen a lot of intellectual property, America’s data, and other things. Occasionally, you can use the same thing for action. Computer network attack as opposed to computer network exploitation.

At the lower end of that spectrum is distributed denial of service, which is taking you offline for a while, harassing you and overloading your system so you can’t access an ATM or get access to a website. That usually passes over time. Cyber is a perishable capability as you go in and figure out what happens to you. There are more extreme versions of that, where you’re attacking an electrical power grid or other things.

Do you see that as a big risk?

Yes. It’s a cyber world. A couple of things, our attack surfaces are increasing substantially. We’re more open. There’s a cybersecurity arms race going on but there’s always a soft spot somewhere. Not everybody can afford the best defenses or see the threats coming in the way that some parts of the US government can. It’s a big threat.

The key point about that one, though, you could also apply it to information influence and others, and indirect conflict. In addition to getting your domestic house in order, winning the arms race, and having the world’s leading economy, this is where you’re going to fight. If you fight in the next one, we’re going to talk about far more significant consequences and complications, but this is where most of it’s going to go on. You’ve got to be on the offense and do a range of things to prevail in that area, if you’re going to win.

The next one is strengthening regional and global deterrence and if required, defeating aggression. It’s very interesting what you reference in the book. You talk about the Navy and investment in maybe less expensive ships, but at a greater number. Investing in things like the submarine fleet and maybe it’s not the Ohio class. We’ve had an argument over the last couple of years about our investment in these aircraft carriers. Do we need twelve aircraft carriers? With the Ford class aircraft carrier, and it takes ten years to build this thing, is that what we need to be doing?

As I was reading it, it came to my mind almost a bit of the contrary. Something like Israel’s situation, the October 7th attack occurs. What’s the first thing America does? We forward deploy aircraft carrier strike groups. All of a sudden, it’s like, “America is serious because we’re here.” Talk a bit about how you strengthen regional and global deterrence, and be prepared to defeat aggression very quickly and very rapidly as we’ve been talking about before.

As I said, in terms of direct conflict, particularly with China or Russia, but also North Korea, because it’s a nuclear power and it’s right on the DMZ. Iran less so for direct power projection, but I’ll never know what’ll happen there. The problems of China being strong in its area, East Asia, and particularly a threat to Taiwan, but others in the region, and then Russia on its periphery.

How do you strengthen deterrence in those areas? One, you need survivable forward presence. Not forward presence that can be attacked. You need a lot more mass than we have because as I said, we’ve been de-massed by China. You need a combination of high-low mixes, rapid reaction forces, and survivable forward forces.

There are several areas where the United States, like technology still has a big advantage, undersea warfare, global strike space, and the real high end of cyber. We want to continue to lead in those areas because if you lose some of them, you not only lose regionally, but you lose globally. Cyber and space are inherently global domains, undersea warfare is one, and global strike as well.

That doesn’t mean you need to refashion the armed forces just for those areas. It’s like nuclear weapons. You must have them for their existential threat. You don’t make your whole military look like that, but then you have to have the affordable mass. That’s why I think a mix of cheaper but unmanned systems or uncrewed, as we now say these days. Whether aircraft, UUVs, unmanned undersea vehicles, or ground vehicles are important force multipliers. We can only buy so many submarines or B-21 bombers, or other things.

If they meet the same criteria, they’re survivable, they could be forward or rapid reinforcing, missiles versus aircraft, they’re useful for deterrence. As I said, if you look at the world now and think about deterrence, it needs to be in a regional context, but you also don’t want your adversary breaking out and becoming a global power. What stops that? It’s those things I just talked about.

The fifth piece is transforming our alliances and national security institutions for our new era of great power competition. As a new administration has come in, there’s been a lot of talk about isolationism. Are we going to become more isolationist? You mentioned it a few minutes ago. To the contrary, I sat down with some congressmen who said the best way to lose global power is to become isolationist. There are obviously different arguments when we talk about how to build these alliances.

NATO has come under pressure over the last couple of years with respect to Ukraine and the situation there with Russia. How hard has America forced the NATO alliance to come together to combat Russia? Which you could argue pretty well. Now, President Trump has come in and he has gone back to the rhetoric of, “Pay your share. We might not defend you.” The constant back and forth that he’s had over the years. How do we do that? How do we transform our alliances? How do we build them? How are we going to define that? What is the new great power competition?

Again, if you look at the central characteristics, we have this tech arms race, economic competition, competition for global influence, changing balance of power, etc. How do you refashion the government and alliances to deal with this new world? At the end of World War II, where we wanted to come home, what did we have to do in short order? We had to do the Marshall Plan. We had to create new institutions like the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the NSC, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and the Air Force, separating it from the Army and the Army Air Corps. We did all that in a matter of a few years.

We did aid to Greece and Turkey when they were under subversion, announced the Truman Doctrine, then a Berlin airlift, then created NATO in 1949. All that in three years. You ask, are we up to that now with this new world? In some respects, it’s 1946 or 1947 redux. Maybe you don’t need quite that urgency, but you ought to think, allies can be an advantage.

They’re central to American global power and the American-led order that’s been very beneficial for Americans since World War II. Do you need to repurpose them? Is the threat the same? You have a big Soviet army that could come over a flattened Eastern Europe. The geography in Asia is very different than it was in Europe. Also, if economic and technological competition is central, do you need an alliance that helps you in those dimensions as we did ta significant extent in the Cold War?

Maybe more now to give us more economic mass and more advantage. Do you have specialization where some countries can concentrate on some things, either technologically or in their force structure? What kind of expertise do you need to bring into government? A lot of that. We’re on the cusp of a big period of change, and how do you posture yourself for that, both ourselves and our allies, our military, our intelligence services, etc. It’s a pretty big bill.

Also understanding too that the composition of our allies changes. I think we’ve seen a very interesting situation when you look at Israel, the situation in Gaza, the involvement of Lebanon, and their support to Hamas and Hezbollah. You’ve seen the Middle East, in some ways, come together around that, and not on the Iranian side, in support of Israel. Can an ally in that situation like Saudi Arabia be a difference maker?

Yes. There’s certainly the possibility of some regional realignment, which could work to our benefit. That happened in the last two decades of the Cold War, where Egypt came over to our side after the Yom Kippur War, and others like Iran went the other way. There are new actors like a rising India. Since the end of the Cold War, every US administration has been trying to court India and to a lesser extent, Vietnam, so your point about new allies, too.

The point to wrap up these things, the domestic one is the central, and then the tech competition I think is central. If you’re successful in your goals of transforming government institutions, alliances, and deterring conflict, you still have to win. That’s why that third element in there about winning the intelligence war, the indirect conflict, and all the things we had to do in the Cold War to win, that matters.

Let’s talk about the next threat. It’s interesting, you say that we’re in this 1947 type moment, when I’ve spent the last year talking to leaders who’ve said we’re in an interwar period, more like 1939. It’s interesting to your perspective, because I haven’t heard that before in some of the conversations that we’ve been having.

Both can be true.

How come?

It’s because I think the danger with a new Cold War and great power competition is it could go hotter. To some extent, there’s a higher risk of direct conflict between global strategic competitors, China and Russia than there has been, and protracted conflict. It’s a horrible thing to think about, but I think that risk has gone up. In a sense, that part of the competition looks like the 1930s. As you see these rising or recovering, belligerent, aggressive powers, and at some point, is war forced on you, whether you want it or not.

On the other hand, if you think that would be calamitous to everybody unless you win big, and nuclear weapons make that tough. This has a long-term competition aspect like the Cold War. It looks more like the beginning of a period of protracted strategic competition that could have lots of turns to it. It looks more like second half of the 1940s, the post-Cold War period than the 30s, but both can be true. I would say one is likely a subset of the other, though. That’s focused on the near-term war dimension rather than the long-term strategic competition dimension.

Critics in hindsight are 20/20. They know everything. We also know that we haven’t done the greatest job over history of properly predicting the next conflict that we get drawn into. Too often, when we develop our doctrine, when we think about our readiness and our training, and we were fortunate to be in this building a couple of weeks ago, and talk all about readiness with the former Sergeant Major of the Army, Dan Dailey, who’s now at AUSA, we often realize too late who our enemy is, and we prepare sometimes for the wrong thing.

The DOD and the army have been investing heavily in what they’re calling the near-peer threat. Our special operations units have been going back to many conversations and training with regard to unconventional warfare because they’ve seen their place in the near-peer threat as being forward deployed and being advanced elements, having, maintaining, and creating the deep strike capability.

Also, as we alluded to a bit ago, what’s SOF’s job in the near-peer fight will prevent the fight, the nation-state on nation-state, and keep the term near in peer for as long as possible. SOF becomes critical to be able to do that, while our conventional forces increase long-range precision fires, invest in deep strike bombers and other capabilities, depending on what their service component is.

Although, there are many who believe that we face a direct conflict or a high-intensity indirect conflict with Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, there are many who believe that the vacuum that has been created in Afghanistan has led to a resurgence of Al-Qaeda of Islamic fundamentalism. We have reports and we’ve seen the stories of Osama bin Laden’s son now who is creating a significant organization coming out of Afghanistan. What do you see as the next biggest threat to America?

I think the greatest threat is combination of China, Russia, and perhaps adding in Iran and North Korea. The possibility of direct great power war is still a reasonably low one, even if it’s increasing, and it’s something we ought to take seriously. DOD doesn’t like to plan now for more than one war at a time, and usually against not a peer, but somebody lesser. That’s not the world we have. You have to, at the extreme end, think about what it would take to defeat a combination of these big countries. Nuclear weapons are still a big leveler for everybody.

You also can’t ignore other threats. Global jihadism hasn’t gone away. What you don’t want to have happen is take your eye off the ball and say, it’s all this. I remember in the Pentagon, we would have these debates, “Do you want me to do China or Al-Qaeda?” “I want you to do both.” It’s not either or but then you need the right balance and mix and others. I think the Soviet-American Cold War is instructive for a range of things that SOF might do. It’s not all that SOF would do going forward. For instance, you mentioned 10th Group at the beginning of our interview.

When I was there, we were oriented toward Europe and the Soviet Union. Half of us were going into Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, so we learned those languages. I had learned Russian and Czech. We also learned direct action skills like special backpack nukes and special atomic demolition munition that I was trained on and learned to parachute with and things. The other half of the group was for stay-behind missions if they were overrun, working with people who were overrun.

You can imagine that certainly now in a big way of being helping locals defend themselves against direct aggression, as well as possibly liberating captured areas, the UW part that you mentioned. Also, then there’s this global competition for influence. The things that SOF does to try to prevail in this below conventional conflict struggle of influence is very important. They’re uniquely capable of doing that. Direct action and special reconnaissance could also play a role. Almost every mission you could think of beyond counterterrorism or counternarcotics applies to great power competition just in different aspects.

As I said, the great danger of turning our back on terrorism, you could still have a big attack and then it could divert you strategically. I don’t know when the global jihadist idea will be so discredited that it goes away, but it isn’t any time soon. Our strategy has to be aimed at keeping them down and keeping them off balance and not letting that threat gather again, as we unfortunately did in the past.

Where do you think SOF needs to focus? How do you see SOF’s integration with the conventional force over the next decade?

Find what you’re good at and then be passionate and aggressive about it. If you do that, you’re going to be successful.

If you looked at, again, direct great power war, like in the original Cold War, things like special reconnaissance and direct action can be contributors. If areas are overrun where conventional forces have to take it back to deter that or to make it tougher, the porcupine defense idea, that stay behind is a very powerful role. It’s not directly in support of conventional forces, but it’s very broadly in support of the strategy. They’re our first line of defense, essentially.

The indirect conflicts, if we don’t want to commit direct troops, even to an indirect fight, then SOF would play an important role there, too. One of the mistakes I think I had early in the 80s, I’d gone to CIA, but was coming out of Vietnam tending to see SOF as, “You did Vietnam, but you’re no longer relevant. You can do these few things, but if war breaks out in Europe, it’s going to be this massive war.” That may be true, but there’s still things you can do to help that.

Do you think we’re seeing some of that now? It’s because I’m hearing a bit of that. Especially when it starts coming down to what we’ve seen in 2024, is a reduction in funding. We’ve seen the directed reductions in force for SOF elements.

You do want to transform the services within them, and then to a lesser extent across them. We tend to focus on the across part more, but it’s the same logic that China’s our biggest threat. It’s air, maritime, space, and cyber. There’s no role for the Army, and there’s not much of a role for the Marine Corps and for SOF. That’s just one threat. It’s like nuclear weapons. We talked about that earlier. They’re critical. I used to oversee them, but our nuclear strategy and one job. You can’t have your whole military do that or your security would be weakened.

The same is true for some of the things that are valuable to deter China, global long-range strike, the ISR that goes with it, and undersea warfare. You need that to deter and, if necessary, defeat, but you’ve got a lot of other stuff going on. Both the conventional forces, the ground forces, and SOF can still play important roles in those things. There’s still people fighting over land. They’re still on land in some ways. Given the anti-access threat, it may be as the Marines had done under General Berger, you emphasize long-range fires and smaller groups than amphibious landings for just that threat. That may be true.

For the Navy, it may be more undersea warfare and less the surface ships. You have to look at how much of this do I want versus how much of that, but you end up needing a mix. One of the things we talked about is counterterrorism. One of our most effective weapons against Al-Qaeda was the Predator and Reaper. It provided armed ISR and persistence that nothing else could provide and with enormous precision, the most precision of any aircraft essentially.

It enabled us to take down Al-Qaeda and a country like Afghanistan-Pakistan border region that we couldn’t reach any other way. After you say, “This thing’s no good against China.” It might be useful in certain aspects in phase zero and others, but it’s clearly great in counterterrorism. Nothing you’re going to buy for China is going to deal with that terrorism problem. You ought to spend some of your budget on things like that. It’s not all the latest whiz-bang stuff. It’s stuff that does a mission to perfection.

Do we get overconfident as Americans? Do tend to think back on our successes and maybe put them a little higher on the ladder than they’re supposed to be? Also, don’t put enough value or stake in some of our losses. I ask the question because you brought up in the book the importance of some of the failures that we’ve had, the war in Yemen, and some of the serious stuff. When we look forward, we hear the rhetoric out of our leaders. I’ve sat down with so many leaders who talk about, “When it comes down to it again, America will be ready. Regardless of what it takes, we’re going to get it done.” Are we overconfident?

I think it cuts both ways. To some extent you can but you can be. You could also be too depressed that you’d have no chance. That’s equally bad or worse. The right way to approach it is to be very clear-eyed about it and do what it takes to win. The reason I wrote about successes as well as failures in the book was one to show the range of things that I was involved in. More importantly, to say why answer the question? Why did we win in this case doing this kind of operation?

For instance, supporting an opposition movement or resistance? How could we defeat the whole Soviet army in Afghanistan, yet not win in Syria? There were certain choices that were made that led to that outcome, and we could have won that in a variety of ways and I talk about that. Why did we do so well against Al-Qaeda in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region and it took much longer in Yemen? It was certain constraints that we put on Yemen that we didn’t do in the other place. You ought to learn those lessons.

If you go into one for general purposes, but if you’re going to do one of those operations again, you can see this increases your odds of winning and this doesn’t. As you said, you can have confidence that just because I can win a big battle, doesn’t mean with the same force win the smaller battles or the war in the shadows. You can have overconfidence from thinking, “I’ve got the best military in the world.” Meanwhile, I’m losing in lots of places. Why is that? You’re applying the wrong ways and means.

You’ve got to have the political will.

Again, there’ll be lots of new things going forward too, but what we have since Thucydides, history is a pretty good indicator of mistakes people have made in the past and clever things they’ve done, and you ought to learn from it.

Let’s talk about leadership. At the end of the day, I believe and I think you do too that our Green Berets make some of the best leaders, if not the best leaders that are out there. That that leadership transcends their military service being out now, being an entrepreneur, starting businesses, or working with others.

We’ve built an entire company that seeks to bring in Green Berets at every opportunity. You highlight these ten principles of leadership development. What I want to do is I want to throw them out there. If you would, we’ll do like a bit of a rapid fire. I’ll throw it out. You tell me quickly exactly what it means. The first one, take only jobs you like and think you can make a difference.

This is my reflection on my career. I wouldn’t call these universal principles, but it’s what animated me, and what I would say is we tell our young people, “Pursue your passions.” We got to be good at it. I wanted to be a baseball or football player, and I was pretty good, but I wasn’t good enough. Find what you’re good at and then be passionate and aggressive about it and aim high. I wouldn’t be an absolutist about this principle, but it shows that finding what you’re good at and you love, then you’re going to be successful if you have both of those things.

Expert and referent power.

This made a big influence on me when I first went into the army and was getting leadership training at the infantry school and elsewhere as part of my Special Forces training. You have the traditional forms of power that my position in command gives me authority, and I can give punishments or rewards. There are these other kinds of power of sociologists. The sociologists in the late ‘50s had written about this like doctors and others, scientists, that it’s experts. It’s real expertise in a thing.

It’s sometimes in informal organizations. You have the formal structure and the informal structure. People know who can organize the group and come up with good ideas. It’s less rank-conscious. You see this in startups and fluid organizations a lot. That fit me psychologically perfectly in terms of Special Forces. I thought, we’re supposed to be the best individual soldiers and you should strive to master all the skills you need to do that as a special operator or CI officer because you’re out there alone and unafraid, or at least with a few band of brothers.

That struck me a lot. Early in your career, you want to try to become some of the best at it. If you are a good leader, be alert to opportunities where people will let you have outsized influence. That was true for me in Special Forces. I got early command. I was blessed by mentors, but in the CIA as well, for the invasion of Grenada and Afghanistan, and others. They allowed me to have responsibilities way above my grade level.

That brings on number three, which is, take on more responsibility.

One of the things that impressed me later was being alert to that. A former CEO of Goldman Sachs, Hank Paulson, who was Secretary of the Treasury in late Bush, said one time that job enlargement was key to success at Goldman. He was doing very well in certain areas, but bosses sometimes said, “Could you take on this?” You learn a lot doing that.

As I thought about it, I thought I got pretty good in the early stages of my career in special operations, intelligence, and covert action. In the intermediate phase, when I went for my MBA and PhD and then did some think tank work before coming back into government, I learned a lot about nuclear weapons and future warfare. Suddenly, when I had responsibilities for transformation and nuclear strategy, I knew a lot about it. It’s that depth and then broadening.

Our military education system, at least in the army, tries to follow that in the conventional realm in a sense of, first, you learn your branch at a very narrow level, other branches, other services, and strategy, and supposedly it produces a good senior officer by the time you’re done.

That’s where you’re talking about in number five, develop this deep experience in one area and broaden that out. Another one here, have mentors.

They were central to my career. As I say, from enlisted in SOF, they gave me big opportunities. I might be the 11th ranking man on a twelve-man team and was given bigger responsibilities for tactics and other stuff when I showed I could do it and then command and being one of the first couple of CIA people on the ground in Grenada with the invasion then Afghanistan. Finally, these bigger jobs in the Pentagon. At each stage, people believing in me that I could do more than what I was doing in my current job.

You talked a bit in chapter six about building and rebuilding intellectual capital because the more you know, the more educated you are on certain topics and it becomes critical.

Success isn’t final. No matter how great your achievement, you have to pass it on to others and adapt to ensure continued success.