Alpine ski racing World Cups and Olympic medals are won and lost by hundredths of a second by skiers hurling themselves down ice covered mountains with only a thin metal edge to control decent. These feats of speed, athleticism and precision breed competition, a healthy dose of fear, and awe for all of us who watch and have dreamt of standing atop the winner’s podium. Beijing 2022 is here…and it’s time to kick off The Jedburgh Podcast tribute to the Winter Olympics.

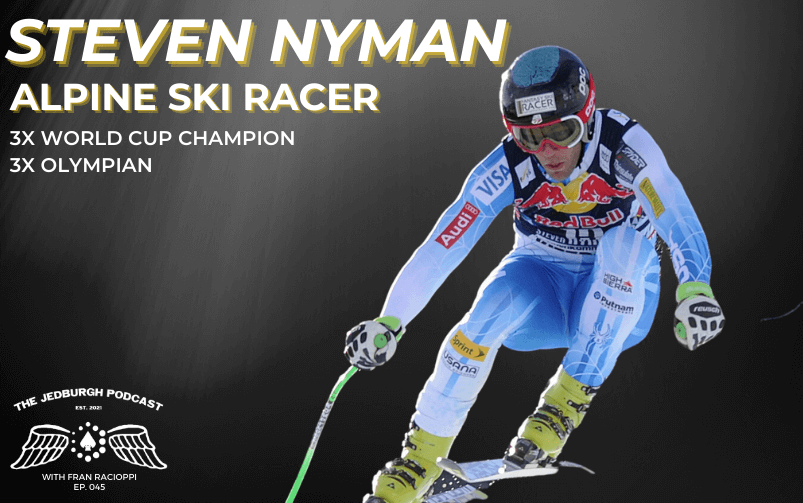

Steven Nyman, is an American legend in downhill Olympic and World Cup skiing. He has reached 11 podiums, earned three World Cup titles, and did something no other American downhiller has ever done—reaching the podium four times in a row in the run up to the 2018 Olympics. He has been on the US Ski Team for over two decades. Steven joined host Fran Racioppi from the World Cup circuit in Switzerland to discuss the importance of preparation, the fear of failure, the courage to act, the grit needed to recover from devastating injuries and the drive to win after 20 years of competition.

—

[podcast_subscribe id=”554078″]

Skiing is a simple yet complex sport. In theory, we strap a pair of sticks to our feet, and then we haul our bodies down an ice-covered side of a mountain with only a thin metal edge to control our descent. In practice, the simple act is a dynamic balance of physical capability, technical prowess, mental and emotional strength.

World Cups and Olympic medals are won and lost by hundredths of a second by skiers traveling over 80 miles an hour, covering several miles of distance in thousands of vertical feet. These feats of speed, athleticism and precision breed competition, a healthy dose of fear and off for all of us who watch and have ever dreamt about standing atop the winner’s podium. Beijing 2022 is here and it’s time to kick off the show’s tribute to the Winter Olympics.

Steven Nyman is an American legend and downhill Olympic in World Cup skiing. He’s reached 11 podiums, earned 3 World Cup titles and did something no other American downhiller has ever done, reaching the podium four times in a row in the run-up to the 2018 Olympics. He’s been on the US ski team since he was nineteen years old.

Steven joined me from Switzerland as he prepared for his final qualification event in the giant slalom and downhill competitions. A strong performance here would earn him a spot on his fifth Olympic team. Steven and I break down ski racing, the physical demands, the technical skill and the mental rigor needed to compete and win at the highest level by the slimmest margins.

Steven also talks about the importance of preparation, the fear of failure, the courage to act, the grit needed to recover from devastating injuries and the drive to win after twenty years of competition. Steven and I both shared the boyhood dream of racing in the Olympics. He is still pushing the limits of competing. I’m thinking there’s still time for me.

—

Steven, welcome to the show.

I’m fired up to be here. Thanks for having me.

People ask me all the time what’s the best part about hosting a show. I tell them that I get to talk to amazing people who’ve done the coolest things. More importantly than that, because I’m the host and the creator of the show, I get to pick the topic and say, “I love this. I don’t want to talk about that. We’re never going to do that episode.” I have a good amount of readers, too, so I also get to talk about things that they care about.

When I was thinking about the Olympics, I was like, “This is right in my wheelhouse. I grew up skiing. It’s a huge part of my life. We have to cover the 2022 Olympics.” You are joining us from the first European edition being in Switzerland of the show, so I get to talk to one of the most famous and well-known men’s US skiers ever in the history of the sport. It’s truly an honor to be here. I have to caveat this whole conversation with the only commonality that we have in skiing, between the two of us, is we both started skiing at two and we both wanted to be Olympic skiers.

The difference is you achieve that. Somewhere along the way, I went a different path. Other than that, I’m not comparing myself in any way to you. A lot of things happened. I always thought, “When will be the year in my life when I’ll get to go to Colorado or Utah for the winter and work at a ski resort, live there and that will be the catalyst to me becoming some championship skier?” I realized that I’m old and that’s not going to happen, although you’re pushing it and still in it.

You could always be lifty. You’ve watched a lot of movies about Aspen Extreme and the classic ski theme movie right there. Maybe you can create your own success story and sell the whole story right there. There you go.

From show host to lifty at Breckenridge, as long as I’ve got the free pass. I have epic passes. We’re almost free, considering how much they dropped the price. I got a military discount.

I always look back at my life and I’m like, “How did I get here?” For one, I’ve been on the US ski team for many years. Two, how am I competing at the top level for so long and pushing myself every day? A lot of these guys that I traveled with, they’ll complain about this or that like, “It’s dumping in Tahoe. I’m missing it.” I’m like, “You got an entire mountain shut down for you to go as fast as possible on yourself to the max. Don’t complain. You’re a downhill ski racer. You don’t have to wait in the lift lines. Everything is free. Who cares about what’s down in Tahoe right now?”

[bctt tweet=”To remain clear in your mind and have that belief of what you’re capable of is very important.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Let’s talk about the games. The games are in Beijing. You’ve competed in three previous Olympics, 2006, 2010, 2014. You qualified in 2018, but then you were injured. It’s the final qualifying round for the 2022 Beijing Olympics. When you think about the possibility of competing in your 4th Olympics, qualifying for your 5th, what’s that mean?

Honestly, physically, I feel great. The biggest thing is everything that I’ve overcome, the past few years have been brutal, physically and injury-wise. To be able to do it and get there for one, with age, and you can attest to this, we become wiser and have a better understanding of everything. I don’t have the balls that I used to have, but the balls that I used to have got me in trouble. I make all kinds of mistakes. Now, I have a good understanding of what I’m trying to do, how I need to do it and what it takes to get there. The consistency and the longevity are what I understand. I’m not willing to risk it. I have two kids, a family, and a lot is riding on the line there.

One of them would be to do it and have my daughter watch. I have a daughter who gets it and usually it’s her crying, “I want to get out of here. I don’t want to deal with this,” in the finish area, but now she’s like, “Dad’s on TV. He has a green light. He has a red light. Red lights are bad. Green lights are good. Go, dad.” When she was watching TV and dad had a lot of red lights, she was like, “Dad has a lot of red lights, but we still love him.”

To inspire her and others, that’s incredibly meaningful to me. A lot of people talk about how that’s what my career is, but I truly believe I can compete and win. My results haven’t shown it in 2022, but I do believe I can. I’ve shown a lot of speed and had a lot of mistakes. If I can refine some of those mistakes, I can be ready there with the course.

Let’s break down skiing as a sport. I want to do this because I’m extremely interested in your perspective on all of this and also to break it down a little bit for those readers who might not know a lot of the backside and the technical aspects of the sport. When I think about skiing, there are three components to the sport. You can certainly correct me if I’m wrong, add or subtract, but I think about the need for a physical capability. That’s number one.

Number two, there’s a technical skill requirement in terms of both the technique that you have to exhibit physically and the equipment side of things. There’s this emotional aspect, the trust and confidence that’s required at all levels. It doesn’t matter if you’re a beginner skier on the bunny hill or an Olympic racer at 90-plus miles an hour. You have to have trust and confidence in what you’re doing.

I want to break down each one of these. Let’s start with physical capability. Fitness is a huge part of your success, longevity and training. I watched some of the races you competed in in the past as I prepared for this. One of the announcers at one point called you a specimen. You are 6’4” and 220. You’re ripped. I work out every day and was a Green Beret, but I’ve got nothing. I can’t even go there because of the absolute and phenomenal physical condition. Can you talk about the physical requirements of skiing and the difference between a recreational skier like me and an Olympic athlete or competitor like you when it comes to having to physically prepare for this sport?

It so happens that this race, being in Switzerland, is the longest race on tour. It’s 2.5 minutes long. It’s the most physically demanding, in my mind, because you’re going for an all-out sprint. It’s an 800-meter dash and at the end, there’s an S turn in the finish that is brutal. It’s so hard to muster the confidence to stick it in there and push hard. I’ve lost in a 10, 15-second segment, but it’s because I was so gassed. You’re not able to do that.

For one, we need endurance. There are a few types of endurance. There are long days on the hill. We’re out there for 4, 5 or 6 hours of training in the cold. We have to recover between those, run to run and next training round, which is usually 1 to 1.5 minutes long, train our bodies to flush that lactic acid out and feel refreshed to where we can execute those movements in a high manner over and over.

At times, he also wears almost nothing but a thin suit.

There’s that and on a thin metal edge, in spandex on a sheet of ice with a little suit and a helmet. It’s what skiing is. It’s bouncing on a thin metal edge on a sheet of ice. There’s the endurance aspect, technique and guts, but you have to be able to remain focused and assess all this information that’s coming in and assess your body like, “Am I capable of this?” Make a plan throughout the run. “I know it’s risky here. This is where I would give it less and try to recover a little bit so I can risk it more in other sections.”

There are so many different aspects to skiing. I could go down a whole rabbit hole. I’m not being super clear with this, but there are the G-forces and vibrations. The sheet of ice is not like you’re on a hockey pond. This is the side of a mountain. They spray down with water and it freezes, so you’re constantly getting bumped down on one of those vibe machines in the gym. Those are vibrations plus those vibrations on 90 miles an hour down these things in a squatted position and then you’re putting a few Gs on top of your back. That’s brutal.

Steven Nyman: “A lot of the trainers think it’s all about strength, but it’s about coordination. It’s the ability to focus and to precisely move and balance.”

To remain clear in your mind and have that belief of what you’re capable of is super important. Training-wise, in the summer, we do a ton of endurance. I structure my weeks like this. Mondays and Thursdays are overall lower body days. I built myself in the gym underweights, usually circuit-style training followed with some balance aspects.

Training-wise, Mondays Thursdays are the overall body. The greatest trainer that I ever had was an Austrian Special Forces. He had this theory of fatiguing the entire body. We would alternate from anterior to posterior, upper body, lower body, core and 18, 20 exercises to fatigue the entire body. When we’re fatigued, go jump on a slackline, go do some coordinated drill, other bounce drills whatever it is, try to function under fatigue. He trained through functioning under fatigue and his whole thought was, “In those last 30 seconds, if you can set yourself apart and focus when you’re pushing against the wall, that’s when you’re going to set yourself apart.” Everybody’s pretty fast and good skiers. That’s where you can get your advantage.

Steven Nyman: “If you can focus when you are pushed against a wall, that’s when you are going to set yourself apart.”

We’ll do something like that for Mondays and Thursdays. Tuesdays and Fridays are core. Skiing is so much core. You think it’s quads and big butts. It’s resisting those forces, trying to stay over the outside ski, moving forward and staying over your skis as you’re going down the hill trying to go faster. We’ll train all kinds of various core exercises, but that’s all you’re focused on during the day and that’s not crunches. It’s like on a slackline with weights overhead with bungees bouncing off the sides of your barbell with other weights wiggling left and right. You’ve got to stay aligned, balanced and moved side to side, whatever it is. That set me apart and taught me a lot.

We’ve had a lot of trainers and a lot of the trainers think it’s strength, but it’s not strength. It’s coordination, the ability to focus, precisely move and balance. Skiing is bouncing on a thin metal edge on the ice. In the afternoons, it’s about recovery or developing those anaerobic systems and aerobic systems. I’ll do some intervals, usually on the overall body days and the lower body focus. I’ll do more about recovery for 1 or 1.5 hours, easy bike, hike and jog. On the core days, Tuesdays and Fridays, I’ll do some interval training and build up throughout the summer. I’ll start at 5-minute intervals and by the end of the summer, you’re going into 10-minute intervals pushing that lactic threshold level higher and higher.

On Wednesdays and Saturdays, it’s usually a long-endurance, 3 or 4 hours of wandering through the mountains like hiking, exploring the mountains and continually moving for that long amount of time. That’s what we do. A lot of our training days are long days out in the mountains. It’s cold and brutal. That’s how I train all summer. It’s not rocket science. A lot of people get into it, overthink all these things and look at all these energy systems. It’s training yourself to be able to focus under fatigue and build your body up to take hits because crashes are brutal. If you can take a hit and get back up, that’s going to allow you to race more and more.

The technical aspect comes next on this thing. I caveat that in terms of the technique, which all stems from your ability to be physically fit, there’s also this equipment. Different races require different types of each, both different techniques and some different equipment because there’s different terrain. There are so many different things out there. I call it Gucci Gear. They’re trying to get you to buy all this stuff and tell you that this is going to be the one little thing that gives you this improvement.

This is an important part of it because the margin of error in this sport is so small, fractions of a second. You won a World Cup by 3/10 of a second, which is an eternity of time in skiing, but you’ve also missed winning and other podiums by less than that. Sometimes, 200ths of a second put you out of it. It’s crazy to think about that small amount of time when you have to travel the distance and the elevation change that you do at 90 miles an hour, yet the difference between being on the podium and not is 1/10 of a second or 100th of a second.

When we were kids, we skied on skis that were 210 centimeters tall and straight. We had 1 set of boots and now, I have 3 sets of skis. They all do different things. My wife’s like, “Why do you need another set of skis?” I’m like, “Everyone needs four sets of skis. They do four different things.” She’s like, “You grew up skiing on 1 set of skis for 20 years. You don’t need four sets of skis.” Talk a little bit about the equipment, why it is important, the evolution of the technology and how it’s changed the sport over time.

When we were kids, we were right on the cusp of carving skis and it was around the turn of the century, which sounds like a long time ago. The skis were long and straight. It was a lot of quads and butts. Grind it, twist it and maneuver it. The skis do a lot of work for you. They’ll carve, but we have a lot of regulations on the World Cup tour to where we can’t make the skis carve easily. They’re very long and straight still and we have to ski with the proper technique and stay over the skis.

[bctt tweet=”It all starts with you. What’s your vision? What are those things that you see? Are you willing to actually do it and risk it and go?” username=”talentwargroup”]

Say this is the ski and that’s downhill. This is my body. If I’m going down the hill and continuing moving with my skis, that’s great, but if the skis are moving and I’m going like this, the skis are going to take you for a ride and not vice versa. You want to tell the skis where to go. Bad things happen when the skis take you for a ride. It’s staying over the skis. That’s 4.5, but side to side, you also have to stay over the skis there, continue to get them to grip into the ice and move through that turn. For me, it’s been a long battle of figuring out the equipment. That’s the theme of my career.

Skiing isn’t built for a guy like me, 6’4” and 220. Everything’s designed around 5’10” guys and the boot size, the 25.5, which is a size 8 or 9 shoes. I have a size thirteen shoe, so for a boot, I have so much leverage on it. It doesn’t deliver the energy to the ski the way that it’s designed to deliver the energy. When you’re flexing forward the lower part of the booth, it bulges out and the energy goes to the side, not to the tip. I kept explaining this.

There’s also another language barrier I deal with, mostly Europeans and German-speaking folks. I don’t speak the greatest German, so a lot is lost in translation. I keep expressing my feelings and they’re like, “It’s not the boot. Try this or this.” They’ll go every which way and I spent 3, 4 years, what I called my dark years battling and trying to stay up, do well and finish. I got lucky here and there. I’ve extended my career but in the summer of 2014, I was given these boots that threw fiberglass on the sides to prevent it from bulging out like this.

Steven Nyman: “The ability to assess the situation, change, and adapt immediately is through repetition through work.”

All of a sudden, when I go forward, it delivers the energy to the tip instead of out to the sides. I was like, “I have something I can push on. The skis are reacting. This is so much easier than it’s been for the past several years.” That also occurred because I did and ascended well. I made the ski team in 2002 as a slalom skier. I broke my leg and got good at speed skiing. In slalom, the quick turns hurt my leg, so I was like, “The speed stuff’s gone and I’m naturally good at it.” I ended up winning my first World Cup four years later, but then I got bigger, stronger and overpowered everything I had.

We tried stiffer plastic compounds, different stiffness with skis, throwing carbon here and there. Nothing was working. That simple addition of fiberglass was, “It’s gone.” That year I won my third World Cup. The next year I was on four podiums in a row. I was fourth in the World Championships. There is a lot of good stuff because skiing is so much easier. I’ve had four years of extreme balance training on inferior gear.

Figuring that out, understanding that energy transfer and feeling that again, I had felt it in my career and I knew it existed, but I didn’t know how to get it there and get it back. I came back and I have that. It’s what I’ve been dealing with this entire season. I’ve taken 1.25 years off and then I’m trying to make a comeback season for my fourth Olympics.

It’s been an equipment battle all season long because my body is different. In the past years, I’ve blown both knees, torn an Achilles and broke my hand. I don’t have that power anymore and I’m trying to go back to the old equipment. It’s too stiff. We can talk about how it’s a massive component that you have to navigate and it’s extremely hard to navigate being my size because stuff isn’t made for me.

It’s different from a Mugler, which is small and compact. I can’t imagine the stress put on their knees.

I can because I try it every spring and they do it in the middle of winter where it’s sheer ice. My knees feel like they’re going to explode in the spring. That’s what keeps me coming back too. It’s such a complex puzzle. This ski racing and all the little pieces that go into it is not this reoccurring scenario like a football field or basketball court. The snow and surface are continually changing. I know what I ski well on. I like ice and grippy snow, but when it’s soft and gooey, I’m not good at it. I need to work on that and fix that. You mentioned earlier the different tracks.

Wengen here is a gliding track. There is a lot of touches, feel and glide. That’s when you tuck. It’s that egg position the racers get into when they’re skiing, trying to cut through the wind as fast as possible. There’s a lot of that on this course, but there are three key turns on this course that you have to nail if you want to do well in this race. I went a lot of the time in those three key major returns, so I need to figure those out.

Steven Nyman: “There is not a lot of thought. There’s a feeling and there’s a drive.”

There are demanding courses like Kitzbühel that are more vertical drop and in-your-face. You have to create and generate a lot of belief in yourself to risk it to push for the podium there. It’s ever-changing. Every place you go and a week is different. Whatever the weather gods provide, you have to deal with. There’s not a lot of control things aside from your equipment and you have to understand, “Does this setup work in this scenario?” It’s like F1 but more like F1 for rednecks.

Honestly, there’s a bunch of rednecks. It’s like tinkering with little things. Put some duct tape on this and that. It does make a big difference. We’re playing with 0.25 degrees on the base bevel on the ski. The skis flat and the edges on the side, we trim those edges up a little bit when you lay the ski over a bite sooner or later. There’s an edge degree bevel on the side of the edge that makes it bite harder. We are trying to manipulate and change all kinds of little things to make us feel more comfortable to push harder and go faster.

It makes a difference. I took a bunch of classes on ski tuning a while back and I was like, “I can be a ski tuner.” I bought all the equipment and I started to set up the whole thing in my garage. My wife’s like, “What are you doing?” I’m like, “I’m tuning my skis.” After you screw up a couple of times, you realize that those things matter and it does affect the performance of the ski, especially at those speeds.

You brought up the third piece here, which is the mental factors of this. There’s so much that goes into the trust. The words trust and confidence are coming back to my mind: confidence in the equipment and trust in your performance and your ability to perform in these conditions based on your overall capability and training.

[bctt tweet=”Optimal performance is your ability to compete at your best at any given time, given all other factors.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I tore my shoulder years ago. I had come off the North Face at Crested Butte. It’s a ridiculous terrain. I come off and I’m like, “That was awesome. I’m the best.” Right before the lift line, my binding broke. I fell and tore my shoulder. There’s nothing that I can do about it. I remember looking up and being like, “I’m on a green and I tore my shoulder. I can’t believe this.”

This trust and confidence are critical, but you also talked about the uncontrollables. I say, “Controlling the uncontrollable. Focusing on what is in your span of control versus what you’re not.” You said the weather. The weather is one that I bring up all the time. In Special Operations, we always said, “The weather is the number one thing that you cannot control, but it is the first thing that you start getting emotional about.”

It’s like, “It’s raining. Everything’s over. It’s snowing.” You get the first drip of rain or snow down your neck and all of a sudden, it’s like, “I’m freezing. I can’t do anything else.” There’s nothing you can do about it. When you think about controlling the uncontrollables, the mental factors, the trust and the confidence, when do you know you’re in the zone when all of that doesn’t matter when you’re here, you’ve taken it all in and you’re ready to go?

I had a winning streak. No other American man’s done that in downhill. I had that feeling. I knew how my skis were going to react and it didn’t matter. I did it in a blizzard in Skamania, in perfect bluebird weather in Korea and a high windy situation in St. Moritz. Kvitfjell was bitter cold. “Give it to me. I’ll do it.” I was at one with my skis and I knew how they were going to react. A lot of that came from preparation and all the time I’ve spent dialing stuff in throughout the summer and winter, finding that balance and feel. I call it The Tempo on the Skis.

Steven Nyman: “It was just step by step goals…and I just reached for it and pushed for it each and every year.”

When I tell the skis to go, they go. I know when they go, how quickly they’re going to go and pull and when to release the torment. I have these spots I see from each gate to gate. I’ll see this point throwing all my energy toward that next point because that next point is where I’m going to initiate that ski and it’s going to do the same thing. I know how it’s going to react, so I can therefore see those points. I go from point to point and seek more and more speed. There’s not a lot of thought. It’s a feeling and a drive.

One of the keywords that I use a lot in my goal setting is a drive, drive my hands, drive my hips. That drive is that push down the hill and pushes for more speed. If I can get to that point, find that comfort zone, and believe in myself, things tend to be good. You’ve hit those points correctly. It starts with the physical aspects. I have to prepare myself, be a beast and be capable of withstanding these pressures, pushing my body over a long amount of time and bouncing on that thin mental edge.

I have to have my equipment dialed. What’s tough is a lot of that is done over the summer. During COVID, we’re in the summer in Switzerland on glaciers. The snow isn’t the same as the winter, so I’m trying to dial equipment in summer conditions, which is never what it is here in the winter anyway. That’s the problem I ran into. I’ve been trying to unwind that mess that I created and getting the equipment dialed. Once all of that is dialed, it’s like, “What’s that belief? What’s the vision? What are those things that you see? Are you willing to do it, risk and go?”

I want to throw another set of words at you. These come from Rich Diviney, a colleague of mine at Talent War Group, former Navy and author of the book called The Attributes. We interviewed him in Episode 41, the first episode of 2022. He talks about optimal performance and that optimal performance is your ability to compete at your best at any given time, given all the factors. Sometimes it is peak performance, but it might not always be peak performance because the peak is your absolute best given that perfect scenario, but optimal is performing your best based on all the other inputs.

There’s this term mental acuity that he brings up and that’s a mix of situational awareness, compartmentalization, task switching and learnability. Skiing requires this high degree of mental acuity. You talked about going down and picking your points gate to gate, but you’re taking in all this information, all this stuff going around you. You have to have this high situational awareness to see and understand it, but then you also have to have compartmentalization because you have to focus on what’s next so you can’t be thinking about what happened behind you. It’s about what’s coming up.

[bctt tweet=”The discipline aspect forces you to focus, and once you’re forced to focus, things start to become more real.” username=”talentwargroup”]

There’s this task switching. You have all these things that you talked about going on in your body, your legs, core and arms. You have to start thinking about, “When do I focus on what based on what I’m about to happen? What am I about to go through,” but then also learnability. Are you taking the feedback that your body, the course and skis are giving you to then make the changes? How do you triage all that? When you’re in the zone, you’re going out to 90 miles an hour, all this is coming at how do you start making those corrections and thinking about, “I have to focus on this. I can’t worry about this,” making the in-moment adjustments if you will.

The weather can determine a lot, which is sad. In 2015, we had the World Championships in Beaver Creek. That’s one of my most proud runs ever. On home soil, Birds of Prey, Beaver Creek, Colorado, a course that I’ve done well on before. I podiumed earlier that year at it. I hadn’t been healthy for an Olympics or world championship event. In 2022, I’m healthy, ready to go and things are good. I dialed my ski as well as I could.

I skied fantastically, but in the middle of a six gate long steep pitch, you’re never tucking down it. I’m going down this thing and I saw ahead of me that this wind gust is coming up the run. They ran the race on a windy day and I saw it. I grabbed and tucked down this pitch. I’ve never done it ever since, but I could see it and I did it. I instinctively was in the zone and moved. I kept going and fought. I ended up fourth. It was 100 or 200 off the podium, but I executed the way I intended to execute. I did my best. I went beyond myself because I was so in the zone and saw what I needed to do immediately in that situation.

The ability to assess the situation, change and adapt immediately is through repetition through work. I’ve been doing this ever since I was two. I mentioned the gliding aspect. I’m one of the best in the world at that. It’s honestly from Sundance, Utah, where I grew up. They have a front mountain and a back mountain. To get from the back mountain to the front mountain, you had to ski down around The Toilet Bowl and you had this big long flat. I didn’t understand physics, but I chased the BYU ski team down the mountain and these 20-year-old old men and I’m 6, 7, 8 years old. I’m trying to figure out how to keep up with them and find that touch on my skis and glide. It came from that.

Unintentionally, I was developing those skills over time. In ski racing, we don’t get that many opportunities too. If you add up all the time that we’re on a course and we are going through the actions, you can reinforce poor habits. That’s been an American theme to a lot of my ski racing career. It’s like, “We’ll set a course and figure it out.” We got this Austrian coach that came in several years ago and he was fantastic because he’s like, “When I say figure it out, it was 10, 12 rounds a day. Do little things all day long, make a bunch of mistakes and figure out little things. It may come together every once in a while.”

The Austrian coach was like, “You have two runs today. You have four runs today and I’m cutting you off.” You have to perform on demand. When you have that opportunity, you do it. He brought that into our training aspect. I thought that allowed me to perform on-demand and go when I was called upon for race time. I became more consistent when I knew that this was my opportunity and I’m ready because I proved it in training like, “You’ve got two runs. Can you do it? You have this one run to do it, do it.” I found that interesting because I grew up with the set of the course and figured out cowboy style. Here we go. It’s rednecks.

There’s a discipline aspect to it, which forces you to focus. Once you’re forced to focus, it becomes much more real. It’s not like, “I’ll get it the next time.” It’s, “I’ve got to do it now.” Let’s talk about Sundance. Growing up, your parents were both instructors. Your dad ran the ski school. They own a ski shop. Your three brothers and yourself are all amazing skiers. I have to give a shout-out to your younger brother Blake, whom I had the opportunity and the pleasure to work with on one of my previous jobs. I have the utmost respect for him and everything he’s done. He’s an awesome coworker and that guy crushes everything he does at such a high level. Blake, thanks. I appreciate it.

Steven Nyman’s keys to “Sending It With Conviction”

He’s incredibly talented at whatever he does. When we were younger, he was the man. I have an older brother and Blake was younger than me. I’m the second oldest and we have a younger brother Sam, who was seven years younger. Blake was the fastest. He had all the talent in the world. There was a race when I was younger where my older brother and Blake beat me. I hid under my bed and cried, but I’m the competitive one. I’m still fighting at this age. It’s great.

Blake was good at ski racing. He quit and became a good snowboarder. He went back to skiing. He was in ski cross and the movies. He does flips, all those double flips and all this stuff. Blake is good and it’s pretty cool to see it transfer over to the business world. Growing up with those brothers and living on the mountain is one of the major things that developed me in the way that I did. When I was sixteen, I grew up at Sundance and we had the ski team. It was okay. A lot of the time, the coaches didn’t show up and it wasn’t the most structured.

We’d go out freeskiing. We’d challenge and push ourselves on the mountain. When there are gates, we’d go train gates. When I was sixteen, fortunately, Park City had a World Cup and prepared for Thanksgiving weekend. It would be this sheet of ice all winter long and we got a train on that hill. It happened to be that some of the best kids in the nation were all from Park City and it was 45 minutes from me. I worked out a deal with my high school that I got out at noon. I could drive up to Park City and train with those guys and I did.

Is it not a bad deal?

No. It was cool. I created my curriculum. I didn’t have to do PE because I was already pursuing that. I didn’t have to do art. I do that in the summer. Sundance is an art-based community and I’ve learned how to do things up there with real artists. That allowed me to skip those classes, get out at noon and go up there. I was creative because we couldn’t afford the academies, the private schools that a lot of these kids were going to. I had to make it work on a dime. That’s what we figured out and I did it. I got up there and I was the best of Sundance. I was nowhere near the best to Park City. I was little, but I wanted to get to that point.

The first year I was on the Park City B team where your points were under 200 and the point system is you start at 990 and the best guy in the world is zero, so you’ve got to chip away and get down. I was around 200 points, which is 5,000 in the world or whatever it is. I wanted to get to the A team, which had to be under 100 points and I did that. I wanted to get to US Nationals and I did that. I won a podium as a junior. It’s these step-by-step goals. I reach and push for it every single year. I see where I had to go and what I had to do. I competed alongside some of the best kids.

I got to expose myself and be next to other competitors. I thought that team fostered that competitive style, which I look at. I look at these teams. They coddle these kids and I’m like, “You’ve got to compete and foster this battle within these kids. You give out top ten awards. It’s not top ten. It’s the top three. Keep it at the top three.”

I call it grit. I’m on the grit kick because we’ve had a bunch of conversations about it. It’s come up in every conversation and it has come up in the same way that you’ve brought it up. There’s a younger generation that has come up. I’ve tried to pinpoint what’s missing and what’s not there. It’s this grit. It’s what Rich Diviney calls courage, perseverance, adaptability, resilience. It’s this piece of you that says, “I’m going to do this at all costs. It’s going to be nasty. It’s not going to be pretty and feel good, but every time it doesn’t feel good, I’m going to make it feel worse, but that’s what it takes to win, compete at the highest level and operate at an elite level.”

I think of the Special Forces and the things that the guys who were there, the guys that when I went in, I looked up to. I tell a story all the time of the guy who was my team sergeant when I showed up in my Special Forces team. He takes one look at me and he’s like, “How long have you been in the army?” I’m like, “Seven years.” He’s like, “I’ve been on this team for twenty years.” I’m like, “What?” He’s been everywhere and done all this stuff. It’s so different with this younger demographic. You talked about your injuries and how you came back from that stuff. It’s because of grit.

[bctt tweet=”Step back away from yourself, look at yourself, and just critique whatever it is you’re trying to achieve.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I still want to solve the puzzle. It’s this never-ending puzzle. I love the game and I love trying to solve it, but it’s that grit and desire to compete and win that drives me. I’ve been far away from it in 2022. I have 2, 3 good sections. I have two sections on the course that I blew it, but those 2 or 3 good sections are what gives me the hope that I can do this. I am there. I’m close. I need to remain focused and not make those mistakes. I need to execute and dial it in.

People think I’m crazy because I’m old and there’s a lot at risk. Honestly, I don’t feel old, but there’s a lot at risk. It’s more what I’m starting to say. I can hurt myself and I have done that quite a bit. Do I want to go through that again? That’s something that I faced a lot. During this past rehab, I tore my right Achilles in August 2020. For one, I tore my left Achilles in 2011. It takes a lot longer to heal when you’re old. I was like, “I’ll be back in seven months. I’ll be in the World Cup. I got this.”

In 2021, I was like, “I don’t get this, so I’ll take the year off.” I’m in the year and I’m like, “It’s been 1.25 years of not ski racing and there’s a lot of things I’ve got to refine. I’ve been out of the ability to process this information at such high speeds. I’m slow. I can’t process this stuff. I’m scared. Do I want this? Do I want to send it off this blind jump with full conviction?” I had to go through these motions and convince myself that it was possible again. I’m still doing that, but I’m feeling closer and closer and more capable, but time’s ticking for the Olympics.

How do you do it? I wanted to talk about fear and pressure. You brought up fear here. It’s interesting because I call skiing in the mountains in general mountaineering as a great equalizer. There are those things in life that it doesn’t matter what kind of athlete you are or how amazing of a special forces operator you are. I have seen some of our nation’s greatest warriors get on the side of a mountain, be crippled in fear, having to sit there and be like, “It’s okay. You’ve killed 1,000 terrorists, but we’re on the side of a hill. You point them down. If it doesn’t work, fall on the ground, you’ll probably be okay.”

That’s even guys who’ve gone through training. I was fortunate enough to command a Special Forces mountaineering team certified by the Professional Ski Instructors of America as ski instructors. We went up with Summit County Avalanche Search and Rescue crews. We worked and trained avalanche rescue with them. We skied with the ski patrol at Copper, Loveland, Vail, Breckenridge and went on the nastiest stuff.

We had helicopters. We trained with the medevac units and they would drop us on the top glaciers. We’d repel down, cross them, climb back out and they’d pick us up off the glaciers. We’d run all these scenarios, but skiing in the mountains put you in these situations. You said, “Can I launch off of this blind jump with full conviction and know that it’s going to be okay?” It’s testing the mental, physical and technical confidence in every aspect that you could imagine.

“If I commit to that and hammer through it with intention and drive, instead of a little hesitation, I’m going to come out way faster.”

Fear elicits an action. The action is fight, flight or freeze. Courage is our ability to push through and choose one of those, but we’re thinking about fighting more than anything else when we think about courage. How do you do it? You talked about, “I’ve got a will myself to make it happen and do it.” You told the story about the wind coming up on Birds of Prey, tucking and going for it. As we sit here, we have this conversation and think about what’s coming. How do you flip that switch and say, “I’m going to go, it’s got to happen?”

Number one is preparation. You have to have something to fall back on. “Am I ready? Am I capable of this?” Two, we get to inspect the courses beforehand. We slide down and get a look at, “Here’s this blind jump. This is where I got to go,” but I’m coming in here staring at a horizon. I got to think, “I’m going off at 12:30 or 1:00.”

It’s like NASTAR. You’ve got to make a point out of the mountain and go for it.

You’re like, “I’m going to press roughly this hard to get back to the backside of this role, but if I press too hard, I’m going to hit the front side and smack. If I don’t press hard enough, I’m going to fly way too far and crash.” I’ve won three World Cups and they’re all on the same hill, Val Gardena. It has 20 to 30 jumps each year and there are a lot more blind roles. Ninety percent of the field is going to go with hesitation. If I can convince myself on each of these roles to go with conviction, I’m already ahead of 90% of the field.

I’ve put in the time and I know how to judge, assess and figure these things out, but it’s knowing when you’re coming down, “Am I kicking butt? Am I good? Did I dial that in? Am I carrying a lot of speed?” You have to constantly weigh these things in your head like, “I’m going fast. I’ve got to press harder. I’m going too fast. I’ve got to digital speed. I’m going slow. I’ve got to pop this thing.”

I have this little computer inside of my head that’s constantly churning, knowing what’s possible and where I’m at. Luckily, I’ve done these courses a lot before, so I’m making good decisions, but I’ve also crashed a lot on it because I am convincing myself that if I do the wrong thing, I go off and be like, “That was wrong. Here we go.”

The absolute worst feeling is when you’re in mid-air and you’re like, “Oh no.” I’ve done that plenty of times.

Typically, I’m usually not that dumb. When I first made the World Cup, I took meticulous notes on exactly where I needed to go on every roll and everything. In the second year of the World Cup, I reverted to those notes. I was reading them. On the first training around, I went and did the same thing I did the year prior, but it was completely different, which was a big learning lesson, but I went off this jump the way I had the year prior. I sailed and flat landed on my butt. I could barely walk, but I ended up winning that race. It was because I didn’t look at what was in front of me. I referred to something that I had experienced in the past and didn’t enter that race. I called it with an open mind and looked at what was going on. I was stuck in the past and what I knew I could do.

The year prior, I had crashed, but I was fast and I saw how I could win there, but I never had the opportunity to do it, so I was like, “This is my opportunity. Let’s go.” I messed up in one of the training runs, but then I ended up winning the thing. Luckily, at that point in my career, it wasn’t that bad. I was like, “Every day, I have to learn from the past but go into this with an open mind in a clean canvas to paint my picture that day because it’s always different and changing.”

We went through fear and all this stuff. The fear aspect, to revert to that, it’s all about preparation experience. One important thing I wanted to drive was the belief in yourself. I’ve also learned that you can go down these courses. In downhill, there are 1, 2, 3 training runs before the actual race, so we get to go down, we get to try our lines and see other guys do certain lines. We have a ton of video analysis. We get to compare, overlay and see who was the fastest in this section, that section, the next section. Come race day, you got to sew it all together and make it happen. There are a lot of times when I saw the fastest line. I’d go in there with hesitation, knowing I’m going to try this fastest line, but I’m not convinced I can do it. I’m slow.

If I see the fastest line during the inspection and find something that I am 100% convinced that I can do with full conviction, that’s going to be the fastest thing that I can do. If I commit to that and hammer through it with intention and drive, instead of a little hesitation, I’m going to come out way faster than with that little hesitation even though I’m on the right line. It’s knowing who you are, your style, what you’re capable of and committing to that.

For the pressure of the moment, I’m going to quantify this because mentally, so many things come together at the point of execution, especially in athletics. We’ve had previous conversations about this with an Olympic Silver Medalist, one of the greatest women’s rowers of all times, Gevvie Stone.

Gevvie said that she’s motivated going into the starting sequence and at the starting line because that’s why she trains. She trains to compete. This is the moment. Everything she’s done up to that point is to do exactly what she’s there to do at that moment. Laura Wilkinson, Olympic Gold Medal diver, standing 10 meters and 30 feet in the air on the edge of the platform, says that she at that moment can perform because she trusts in her training.

Austin Collie, NFL wide receiver for the Patriots and the Colts, says it’s all about the team. His ability to execute comes from, “I can’t let my team down.” The late Jerry Remy passed away in late 2021, was a second baseman for the Boston Red Sox in the Red Sox Hall of Fame and I asked him about closing pitchers. I said, “How does the closing pitcher get up on the mound?” He said, “It’s because they know that there’s no one else. They have to perform or they lose the game.” It’s all on them and they own that moment. When you’re in the starting block, the buzzers counting down, the front end of the skis are hanging off the edge. The poles are planted. There’s nothing but white ice, as you call it, and some distant mountains out there. What’s going through your head?

In my first year on the World Cup ’05, ’06 season, I qualified through the NorAm Tour. I had a spot. I went to the First World Cups in Lake Louise and I was seventeenth. I went to Beaver Creek and I was 23rd. They were like, “This kid is good. We plan on sending him through those first two races now or we’re taking them to Europe.” I was fast in the training runs of Beaver Creek or Val Gardena, then I crashed. I went to Bormio and ended up 27th, probably the 2nd most demanding course on tour.

In Wegen, I was top 30 as well. Top 30 is usually good. You get World Cup points. It shows that you’re competing with the big boys. I went to Kitzbühel, which is the most daunting mentally. It’s in your face, so steep, big terrain changes. You pick up speed super high and you’re facing massive compressions, big jumps, all kinds of crazy stuff. There are 50,000 to 70,000 people. You’re skiing into a football stadium at the end. I was at the start gate and I did not feel comfortable. I didn’t feel comfortable until a few years ago in that course. I was overthinking. That’s a whole other story.

I was at the start gates and I heard the story of this guy who quit there, a former US ski team. He’s like, “I’m done. I’m not in it. I don’t want to do this anymore.” He backed off and that was the end of his career. I was up there like, “I don’t want to do this, but I don’t want that story being told to me.” That was my thought when I went. I ended up in the top 30, but it wasn’t fun. When I’m in the zone, it’s those points I talked about. It’s that desire to go faster there and there. Get in a tighter position, get back to the ground as quickly as possible, move over that terrain and stay connected. That’s what’s going through my head.

Active and drive are my two words. Stay active and drive. The other stuff is going to come second nature. That’s what all the training has been for. What I’ve done for years and years is develop these good habits. You can develop bad habits, but I’ve developed good habits and bad habits. It’s also trusting in those habits that you’ve developed to come about when you’re going down the hill.

Steven Nyman: “Active and Drive. Those are my two words.”

What’s going to happen is all the good stuff that you’re trying to develop. All you have to focus on is going faster and faster and hitting those points that you’ve gone over in your head, visualized, slipped down the course and memorized. Also, you’ve seen yourself do it over and over and over again. It’s going to go and do it because this is your opportunity.

When I was younger, I would fear away from that. That’s why I’ve put all this work in. All these years, I’ve been itching to race. I didn’t have the greatest race in Bormio, but I had a lot of good sections. I’m like, “I want that next race to come about. I don’t want to wait two weeks. I want to go into it now, work at this and figure out what motivates me instead of fearing coming into these places.” I’ve been there. I’ve come here and I’m like, “I don’t want to be here, but I’m here and I want to be here.” It’s a big opportunity in front of me to perform to make the Olympics.

I’ll tell you because I looked it up that if you make the team, you’ll be older than any American Olympic alpine skier who’s ever been there. Your friends have said that you’re going to be the Tom Brady of skiing. You’re going to go and compete until you’re 50. You have a way to go to set the Olympic record. Winter Olympics is eight set by Noriaki Kasai of Japan, who’s competed consecutively from 1992 through 2018. He’s a ski jumper. Also, the next one is his plan. You’ve got to get to ten to set the Olympic record.

Steven, as we close out, the Jedburghs had to do three things as core foundational tasks every day to win. They had to shoot, move and communicate. If they were proficient in these three core tasks, then their energy could be focused on other challenges that came their way of which there were numerous in their plight in France and World War II. What are the three things that you do every day to set the conditions for success in your world?

The first thing I’d say is to be able to step back away from yourself and look at yourself. Critique yourself in whatever it is you’re trying to achieve. The step before that is setting goals. You have three things. Every day when I get on the hill, I have a little journal. It’s a Google document that I share with my coaches so they can pull it up on their phones. They know what I’m focusing on and what my keywords are.

I hold it to 2 or 3 things to keep it simple. If it’s over the outside, drive the hips, hands and vision, active, drive. They change but setting those goals, being able to step away, reassess yourself honestly and be like, “Am I on the right track? Am I not?” That’s key. Being able to ask yourself, “Do I love it?” That’s what I ask myself every day. “Am I doing what I want to do? Am I committed to it and doing it right? How do I do it?” Those are the three steps.

Steven Nyman’s Three Foundations to Success

Set deliberate goals, step back, look critically at ourselves and do you love it? Is it what you want to be doing? I love those three. We have the nine characteristics of performance as defined by Special Operations Forces. They’re the driving force here on our show, drive, resiliency, adaptability, integrity, curiosity, team ability, effective intelligence and emotional strength. We say to all high performers, “You need to exhibit all of these at different times.” Never all at once but at different times based on the situation you’re in, you’ll have them.

I pick one. I look at my guests and I say, “This is the one that exemplifies you.” You’ve spoken so much in this episode about the drive, not only in the technical aspect and nature of the sport but also the drive to perform overtime the longevity that you’ve shown in the sport. Also, the want and the need to get better, continuously get back out there and still compete at the highest level. I do think of one that I would attribute to you.

I’m going to do something I rarely do here and it’s important. I have full faith and 100% support you as you go out and try to make this team. In this conversation, it’s not just the drive. You set the example on all nine of these because you’ve lived them. You exhibit the drive to get back out there and keep competing. You’ve been resilient year on and year after a multitude of injuries.

You didn’t mention that the last couple of years after the injury have been some of the best years in your entire career. There’s nothing to fear in terms of coming back. Your adaptability to try new things iterates humility that you talked about in your three foundations to look at yourself and say, “What do I need to do to get better?” It’s the integrity of wanting to be there, being and doing what’s right. The curiosity to explore ways to get better, whether it’s your equipment or your technique. The team ability that exhibits with the rest of your team and coaches, the setting of the goals that you talked about.

Effective intelligence, how do you take everything over the years on skis and years on the national team, put it together to say, “I’m going to go out there and do this,” and then the emotional strength to remain calm. Stand at that starting block, get out there and execute. You’ve done it at the highest level of this sport. I am so honored to have sat here and spoken with you. I’ve watched it through the years, 3-time World Cup winner, 11 podiums and multiple Olympics. I wish you the best. Your kids and I will be watching. You demonstrate everything that the Jedburghs in World War II demonstrated, our soft warriors demonstrated out there, elite performers in every organization exhibit. We’re all behind you. Good luck.

Thank you.

Born and bred in Utah, Steven Nyman was skiing at 2. His Mom taught him how to ski while his Dad ran the ski school at Sundance Mountain Resort. Steven and his three brother chased each other all over the mountains teaching and pushing each other to different skiing heights. His younger brother Blake migrated more toward the free-skiing scene gaining several segments in films and magazines around the globe, Michael his older brother became a ski patroller for several years, while Sam, the youngest, enjoys his time skiing for fun. Steven stuck to racing and dreamt of skiing in the Olympics and winning on the World Cup level. While racing for the Park City Ski Team he became a discretionary pick to the 2002 World Junior squad where he landed two medals. Gold in the Slalom and Silver in the combined. Coaches were so impressed, they entered him in a World Cup slalom six days later and he finished 15th! Since then he progressed to win on every level all the way to becoming a three time World Cup 3x winner, a 10x podium performer and becoming a 3x Olympian 06′, 10′ 14′. His goals reach far beyond the heights he has currently reached. Winning on the World Cups isn’t satisfying enough. Steven aspires to be the first American man to win the World Cup Downhill globe (being the most consistent Downhill skier in the world over that particular season), he is also pursuing an Olympic Medal and a World Championship medal! This past season he landed on the podium at the future 2018 Olympic venue, Jeonseong. He also was second place on the upcoming World Championship track at St. Moritz. To say Steven is fired up for the upcoming season is an understatement. In 2011 during a routine training run in Copper Mountain, CO, Steven crashed and tore his Achilles tendon. It was a major setback but without hesitation he got right back to training and rehab. Putting in serious hours in the gym and many days on the ski hill in the southern hemisphere. The season after the injury he stormed back and claimed the victory on a familiar track in Val Gardena, Italy! In his spare time Steven expands his web project, www.fantasyskiracer.com. He has also taken the stadium mic at the Birds of Prey races in Beaver Creek and the U.S. Alpine Championships at Winter Park. Fan reviews where nothing but rave, though his coaches say he’s better at skiing. Steven also has a podcast to help keep his fans updated on his work.