SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson says he’s “just a normal dude,” but he has a very unique story to tell. In 2010, while serving as an 18C on his first deployment as a Green Beret, he survived an IED blast that should have killed him. “If you’re looking straight down your leg,” he recalls, “my tib and my fib were poking out but I couldn’t recognize them because they were so white. It was the whitest thing I had ever seen. And I looked over, and my boot was probably about six inches away from me.”

It was a devastating injury that had him labeled as a battlefield amputee; when in Germany, a temporary stabilization device was applied to his leg, and he was told that he’d be losing his leg when he got home to Brooks Army Medical Center. Still, he says, “If you were going to get blown up in Afghanistan, 2010 was a pretty good year to do it,” due to an early push for limb salvage; “What I was told by the doctors, and my main orthopedic surgeon, was there was a small chance of it working, and if it works, you can rewrite some limb salvage medical books. The worst thing to do is to challenge a Green Beret; then I had to do it. And I started in the limb salvage protocol and procedures.”

Ultimately, his leg was saved, and 18 months later—not without struggle, push back, and controversy—he returned to the battlefield. There were those who doubted his ability to rejoin the fight, but naysayers were silenced when SFC (RET) Hendrickson was later awarded a Silver Star for his actions on 23 February 2016 in Afghanistan.

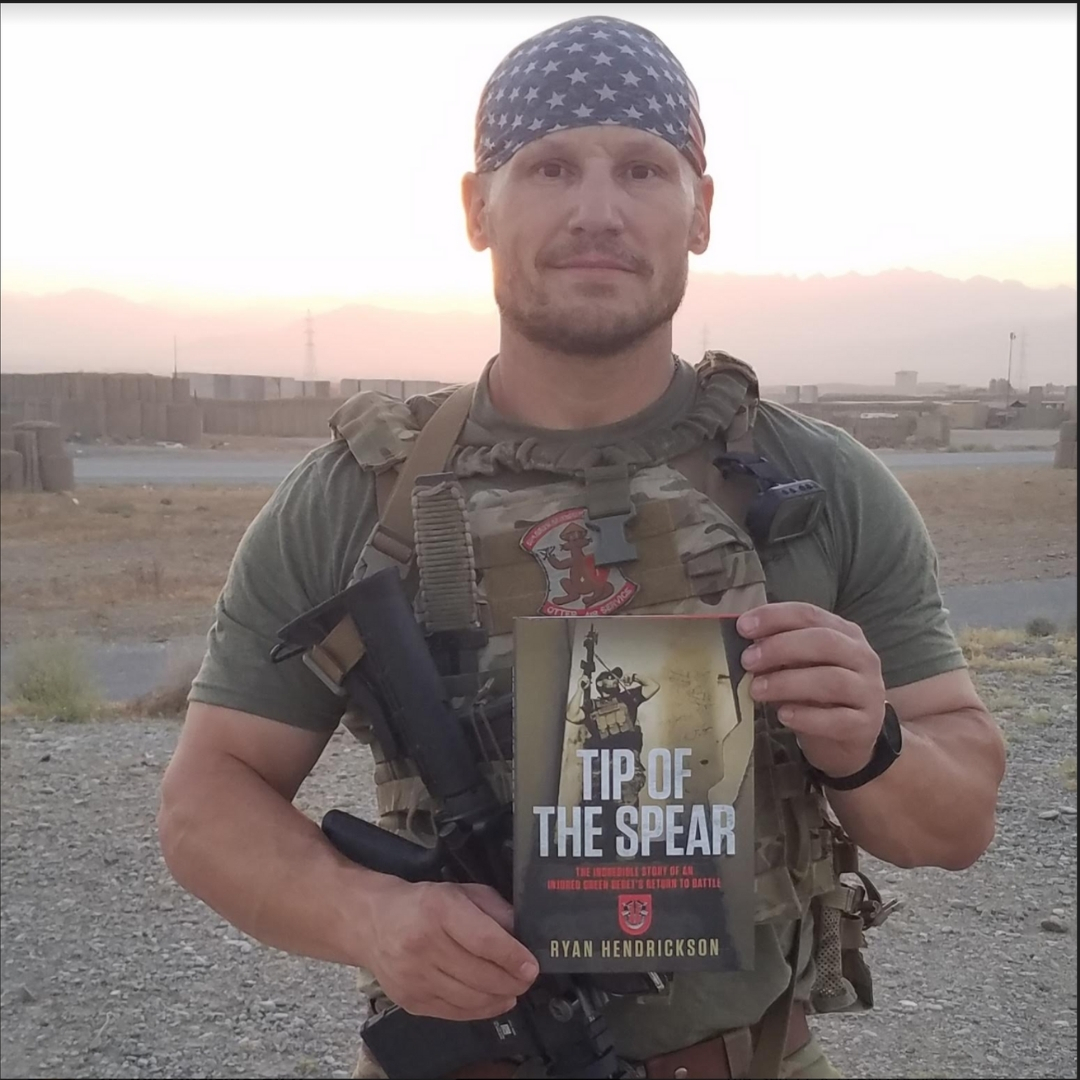

His inspiring life story is now available in his new book, “Tip of the Spear: The Incredible Story of an Injured Green Beret’s Return to Battle.”

He sat down with us for a conversation in anticipation of his visit.

GBF: Why was it time to write a book?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: Honestly, it didn’t start off as a book; writing started off as therapy for me. I’m a normal human being just like anybody else, and in the process of just trying to keep my head straight, I had tried counseling and whatnot like that. No matter who I talked to—the therapist, my friends—I’d leave their office, or leave the bar, and just feel this sense of dead air all around me. I talked to a Chaplain about this, and he mentioned that writing might help me. I blew off the suggestion at first, thinking, “I’m an 18C, not a writer.” Then I went through a long stint in Afghanistan, deploying in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. It was 2017 when I was in Afghanistan that I just opened up my keyboard and started writing. And it really did feel good to get it all off my chest and onto paper. At first, it was just a jumble of emotions and feelings, but I worked back through it and added things until it had taken the shape of more of a manuscript. Still, I didn’t think of it as a book; it was just therapy for me. It wasn’t until I showed it to some teammates on my ODA that my buddy came and told me, “You should look at getting this out there for other people, because it’s important.”

GBF: What was therapeutic about writing your story?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: I felt a relief in just being able to transfer my story from my mind to something permanent. It felt like a weight off my shoulders; like I was taking it and setting it aside. The process of writing would jog my memories, and each time I remembered something new about a situation, I could put it down on paper and then set it aside. Like setting down a heavy load. I’ve had a lot of people reach out to me and ask, “How do you do it? I just want to forget everything.” I tell them: that’s why you’re struggling. You’ll never forget; it’s impossible. You have to learn how to deal with it. The key, and what works, is learning how to deal with that traumatic situation you’ve been through and become functional in your life, regardless of whatever you’ve been through. It’s not a matter of forgetting.

GBF: There was a powerful moment you shared with your dad, that you talk about in the book. He gave you some pivotal advice that was a turning point in your recovery after you were wounded. Can you share more about that and how it impacted your mindset moving forward?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: It came when I was at Brooks Army Medical Center in San Antonio, within that first month after being wounded. It was a time when self-pity was starting to set in, when the survivor’s guilt and feelings that I had let my team down started to kick in. It’s a very dangerous thought process to be caught up in.

My father, a Vietnam veteran, recognized that I was at a very critical point in my recovery. He could tell that I was starting to really fall into depression. That’s when he told me, “You’ve been handed an amazing opportunity; an opportunity that most people don’t get, and others try for that their entire lives. You’ve been handed a second chance. It doesn’t look like it right now, because of the pain, and I know this is a dark time, but this is an opportunity. You can turn this situation into anything that you want. From where I’m sitting right now, you’ve got two options.”

“Your first option is that you could become your injury; you could let your injury become who you are. You can become ‘Ryan-Hendrickson-I-Stepped-On-An-IED;’ that will be forever what you’re known as, and no one is going to blame you for that. You can take that injured mentality, and you can live your life as the guy that’s still stuck back on September 12, 2010 in Helmand province, letting that injury define who you are. But it’s a lonely world and it’s a very dark path.”

“OR, you can use this situation as one of the greatest things that’s ever happened to you. You can use this situation to make yourself a stronger man and a better person, and you can seize this opportunity to be that person that actually benefits people by helping others become better. You get a reset at life. I know it’s tough right now because of the pain, but what you do with this situation right now is going to define the rest of your life.”

“If you choose to become a victim of your circumstances, I promise you: if you live much longer at all, it is going to be a miserable life. I highly recommend that you use this situation to make yourself a better person.”

My father’s words stuck with me, and that conversation is what paved the way for me, and for my positive mindset, throughout rehab.

GBF: It takes a strong sense of purpose to survive what you went through and make it back to the battlefield. What was driving you?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: When I was laying on the ground along the Helmand river, I could hear Taliban on the radio celebrating that I got hit; saying stupid things like they killed 500 Americans, which wasn’t even close to the truth. It bothered me that they were celebrating a victory over me, and it was one of those points in life where I had to admit that they did get me. Still, it’s like what my dad told me; they only got me at that point in time. So, one of my biggest pushes for trying to get back to Afghanistan and prove myself again is that I didn’t want the Taliban to beat me. I didn’t want them to win, number one; and I didn’t want to become a victim of those shitty circumstances, number two. This was the hand that I was dealt, but part of that meant getting back to work. During my recovery, people told me multiple times, “Look, it’s great to have goals, but a comeback is medically not going to happen;” I would just blow it off. By going back to war, getting blown up just became another chapter in my story as opposed to the final chapter. It was a way of not letting my injury change my life. I just stayed focused: I am a Green Beret; now I’m back and still doing my job even though I stepped on an IED and had a limb reattached. There were plenty of limitations and a lot of pain, but the bigger picture was that I was still operating, finding IEDs, getting in gunfights, and doing what Green Berets do. All I did was take a setback and then get my life back on track, instead of falling into a victim role.

GBF: And up until now, we’ve really been talking about the mindset that it took to move past your injury. You also had a freakishly quick recovery.

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: For the most part, the people who don’t know the details of my injury hear that I went back and just figure, “Oh, it must not have been that bad.” People who do know the injury are like, “You’re a freak.” I honestly just think that the life I lived all the way up to the IED, and then what I did with my life afterwards, was all meant to be, and that everything happens for a reason. I went to some really dark places, where without guidance I easily could have been one of the 22 statistics. But I pulled myself out of it because of my backing; I had amazing support, and regardless of what people say, I received nothing but first-class treatment from the military and foundations like the Green Beret Foundation. Everyone reached out to help, so I never felt alone. I can only imagine what it would be like to feel as if no one cared. That would have been a done deal for me. I also believe that the IED I stepped on probably saved a lot of lives; that entire village was full of IEDs, and they were big. Someone was going to die that day if we had kept moving forward. Things happen for a reason, no matter how painful the reason is.

GBF: You go into this in greater detail in your book, but can you walk us through the Silver Star story?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: So, I had volunteered to go back to Afghanistan in 2016. I was in charge of an Afghan IED clearance unit, part of the National Mine Reduction Group. My guys got asked to go on a mission in Baghlan and link up with another team out there. We infiled in and even used Afghan Humvees to do it because we didn’t want to alert the Taliban that there were Americans in the area. The formation had me and my team of 4 Afghans out in front clearing, and then the main element about 15 meters behind us.

The first few IEDs we found were nothing big; we could mark and bypass them. Then we got to an orchard and hit a tripwire IED that, fortunately, didn’t go off. It had a charge in the wall the size of a 5-gallon paint can; it was huge, and it would have absolutely torn through us. Moving forward maybe 5 more meters, I saw people scrambling around these mud hut walls; since it was 1 a.m., I thought, “Oh shit, here we go.” I let out a burst on my M4, and then the PKM opened up. It was like I could have reached up and touched the flame coming out of its barrel.

The first one was 17 meters from our position; they opened up on us and then the wall was just glowing red with AK fire going off everywhere. We’re in the prone trying to return fire as best we could, but rounds were hitting everywhere; the only cover we had was about a foot-high pile of dirt along the road. The PKM fire was pretty relentless, and as the rounds hit, the dirt built up around me would splinter off. I just remember how badly it stung as it hit me in the arms.

My element was pinned down, and we couldn’t move at all. The JTACs, our Combat Controller had to make the decision to drop. I could hear them on the radio saying I was going to get killed, and our terp was saying they were talking about capturing me. It was true; they had an L-shaped ambush set up, and the main element couldn’t get to me. We were pinned down like this for about 5 minutes—which is an eternity in a gunfight—before they got clearance and dropped at 500 lb bomb 17 meters from me. People are going to read the book and go “No way,” but the investigative proof shows it.

The explosion silenced the small arms fire. I stood up with sand falling around me, trying to get my bearings, and my ears were bleeding. We stumbled back to the main element, saw movement again, and called for another 500 lb bomb. We were back 80 meters at this point, but still danger close. Once it dropped, we still had to get into the compound and clear it. I was like “Holy cow, I can’t even see straight right now and I’ve got liquid coming out of my ears,” but I had to get my situational awareness to clear the compound and start clearing the village.

The village was completely full of IEDs; my Afghans cleared 50 of them and I personally cleared 17 out of the ground myself. The whole place was absolutely rigged. We got to our LOA; at that point, the Afghan Sergeant Major came up with the terp and said there was a lot of movement, seeing people that would appear and then disappear. We needed a plan: either exfil, or get ready for a fight. It turned out that the whole village was tunneled; when we moved, these guys were all underground.

We had been on the mission 15 hours already when, around 2 p.m., the first burst of fire came down at us before the tree line erupted. We took 4 casualties immediately from that first barrage of gunfire, as we scrambled for cover and returned fire as best we could. I was in an irrigation ditch behind a small mud hut wall, and I could look out and see one of my guys laying in the road not moving; I couldn’t find two of the others.

What followed was a prolonged, 5-hour firefight. We couldn’t even start dropping bombs for a long time because they couldn’t tell who was who in our lines on the ground. They just kept coming up out of tunnels, and we were engaging dudes at 5 meters. We set up a casualty collection point for all of our wounded, but then these guys would pop out of tunnels right in the same spot, and we would need to move to another one.

Finally, we got to a secure location where we could land helos, but even they were getting shot up. One Apache came in for a gun run and had to leave the are because it was smoking; we were about to go for a Fallen Angel. We set up another casualty control area and started bringing in the wounded; it was then that I got a head count of my guys and realized I was missing two of them. I knew we couldn’t leave them, but there was so much small arms fire, as well as mortars and RPGs. It was the craziest thing I’ve ever seen.

The whole time, we had been recovering bodies of the missing, but my two guys still hadn’t shown up: my NMRG commando Abe, and another Afghan commando. The last place I saw Abe was 500 meters up the road in the direction we were taking fire from. Our Combat Controller talked with the Apaches and said, “Hey, our guys are gonna fly up this road;” the Apaches agreed to do a gun run up the road, with us taking off running behind them. The Apaches came in, ready to go, and we started sprinting up the road with the Apaches doing 30 Mike gun runs straight ahead of us, like something out of a movie. 500 meters up the road, I find Abe and the other commando down in a 6-foot ditch, both dead. This gave us 100% accountability for our men, even if weapons and equipment were everywhere.

It wasn’t easy getting them up out of the ditch, but we brought them back and just suppressing fire the whole time. We could see rounds popping up all around us; you could tell guys were just holding a gun up over a mud hut wall, spraying and praying. Still, we got them back and loaded up.

The craziest thing is that we Americans went out there to do that for our Afghan partners; it wasn’t the other Afghans who ran out there to recover their bodies. It really bothered me that it was our responsibility. I understood that we were teammates and counterparts, but those guys didn’t even attempt to help us because they thought it was too dangerous. It all solidified in my mind that regardless of what country, flag, or color, we Americans are not going to leave you on the battlefield; we will recover you. That was very reassuring for me. Ultimately, that day we had 4 Americans WIA, 12 Afghans WIA, and 6 Afghans KIA.

When I got back, guys kept coming up to me and telling me, “Hey, man, we wouldn’t be alive if it wasn’t for you.” It’s not blowing my own horn or anything like that, but we did find a lot of IEDs. The Major came up to me and was like, “I’m going to put you in for the Silver Star.” That’s how it all happened.

GBF: What did it feel like to come back all the way back from your injury—after people doubted you and even told you point blank that you were going to put others’ lives at risk if you went back on an ODA—and then still contribute so meaningfully on the battlefield?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: Honestly, my main takeaways from that day don’t really have anything to do with the award. I learned a lot about myself in the most intense firefight I had ever been a part of, and I know it ranks up there pretty high with some of the most brutal firefights in Afghanistan. I was really happy with how I operated under that kind of pressure and fear. It wasn’t about the award at all; it was what I learned about myself. They say that we all have “fight or flight,” but you don’t really know how you’ll react personally until all hell breaks loose. When the PKM opened up at 17 meters and I chose to fight, I learned that I have that focus. So, for me, the biggest reward from that experience wasn’t the medal, but proving to myself how I could handle the kind of situation that I was in.

I honestly think that most people want to know this about themselves. I believe that it’s in the fabric of all Americans; even our sports and entertainment are violent. We want to know our limits, and how far we can push ourselves. I believe that everybody has a warrior in them, but each person needs to define it. There are average people every day who are confronted with life-threatening situations and rise to the occasion, digging deep and finding their inner warrior. Some of us chase our tipping points, and for others, that warrior just comes out when they need it. Take the people who fought back on United 93, for example. I believe that everyone has it in them.

GBF: What are the key takeaways from your book and your story that you have for young people, who are sure to be inspired by your example?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: Don’t feel sorry for yourself. Put your ego away. You’re not owed anything. Life is not easy. I think that my story does revolve around the victimization culture that we’re all being affected with. My story is this: you’re not owed anything. You’re nobody special. Yes, you’re special in your own way because you’re a human being, but you’re no better than anyone else around you. Today, people are forgetting that we’re all humans. We’re forgetting how to treat each other and talk to each other.

Society makes life so comfortable that we actually have the luxury of forgetting that life is hard. Nobody owes you anything, and life can be extremely ugly…but it can also be amazing. I want people to read my book and realize that you can go through a life-altering catastrophic experience, but it doesn’t have to end your life or end who you are. You can blow off your leg, reattach it, and go back to combat. It’s not recommended, but it’s the path that I chose. And you can do that. What happens to you in life can mostly be dictated by how you choose to deal with any given situation.

You can’t expect life to be easy, because it’s not. You can’t expect life to be beautiful, either. Life is hard and ugly, but it has its beautiful parts. As soon as you understand that you’re not owed anything, nothing is free, and life is hard, then you can understand that bad things will happen but you just have to keep moving. What other option do you have? Are you going to quit?

GBF: What inner battles do you still struggle with?

SFC (RET) Ryan Hendrickson: The same things as everyone else. Failure. What if I fail? I want to succeed at everything I do. Pain. What if it hurts? What if it sucks? I’m not the gigantic guy on top of a mountain looking down on everybody. I’m just a normal dude. That’s one of the things I really want my story to show people; yeah, I was Green Beret, but I’m just a normal dude. You could become a Green Beret, too; you just haven’t stepped outside your comfort zone and gone for it. What pushes me onwards is the thought that, even if I fail, it won’t be the first or the last time I’ve ever looked stupid. I’ve failed more in my life than I’ve ever succeeded, but every failure has set me up for future successes. I don’t want any question marks in my life. If I try, whether I fail or succeed, I’ll get my answer.

Ryan’s book, “Tip of the Spear: The Incredible Story of an Injured Green Beret’s Return to Battle,”is available online and at major retailers nationwide.