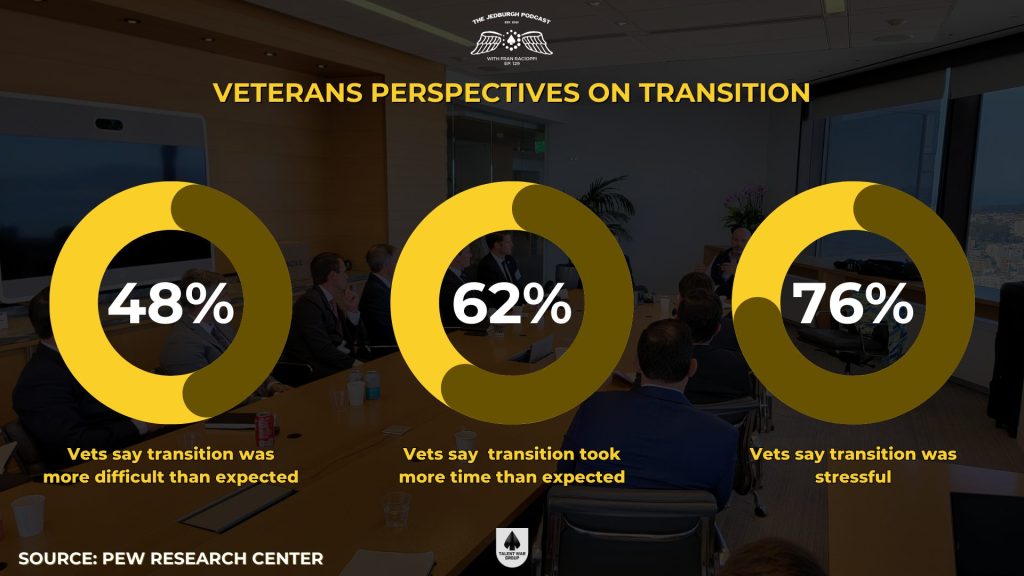

The biggest challenge America’s Special Operations Veterans face is not becoming a Special Operator. Their biggest challenge is no longer being a Special Operator. This transition, despite its challenges, is also a Veteran’s biggest opportunity. Data says that 48% of Veterans believe transition was more difficult than they expected, 62% say transition took more time than expected, and 76% say it was stressful. So, how do we create opportunity from challenge?

For this episode Fran Racioppi sat down with 51 Vets, a non-profit committed to connecting veterans from elite military units with leading business professionals in the finance industry. From the American Legion in the iconic New York City Athletic Club, Fran is joined by Executive Director Lindsey Schiro, Board Member Chris Robinson, and Member Victor Reyna to break down 51 Vets pillars of support, how 51 Vet’s is using their City Summits to create opportunities for SOF Veterans to work at financial institutions, and explain why companies who live by the mantra “hire for character, train for skill” are scaling their businesses on the backs of our Special Operators.

Transition is hard, but the first step is defining the difference between what you want to do vs what you can do. Learn more on The Jedburgh Podcast Website. Subscribe to us and follow @jedburghpodcast on all social media. Watch the full video version on YouTube.

—

Lindsey, Chris, and Victor, welcome to the Jedburgh Podcast.

Thanks for having us.

We’re in New York City. We’re in the American Legion Post in the New York Athletic Club right at the South end of Central Park. Couldn’t be a better place to sit here and talk about veteran transition. That’s my opinion, at least.

On the Marine Corps’ birthday.

You beat me to it because I was going to say happy birthday to you even though you are a pilot. We were in the Marines but is that literally the Marines?

Every marine’s a marine. We all grow from them first.

You guys are here, 51 Vets. Lindsey, you’re the Executive Director. Chris, you’re a board member, and Victor, you’re a member and also a user but a successfully transitioned veteran, as you are too, Chris. Lindsey, you’re the spouse of a special operator. You all bring a unique perspective to 51 Vets, the mission behind the organization. You’re in New York. Veterans Day is coming. As I said, it’s the Marine Corps’ birthday. I’m going to go to the Marine Corps’ birthday dinner after this with The Union League Club with the United War Veterans Council. There will be a lot of hooting and hollering. They’ll be liquored out before we even get in there.

You’re here because you have one of your city summits. I’m going to get into that and talk a lot about how those city summits are impacting veterans and specifically, special operators as they transition out of Special Operations into the real world. We’ve got to figure out what we want to be when we grow up.

I want to start with the challenge of Veteran transition, though. I’ll give you some stats from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Forty-eight percent of veterans say that transition was more difficult than they expected. I’m in that 48%. Sixty-two percent say the transition took more time than expected. I’m a few years out and I still don’t know if I figured out what I want to be. Seventy-six percent say it was stressful. I had no gray before I transitioned.

I want to start with the challenge of Veteran transition, though. I’ll give you some stats from the Department of Veterans Affairs. Forty-eight percent of veterans say that transition was more difficult than they expected. I’m in that 48%. Sixty-two percent say the transition took more time than expected. I’m a few years out and I still don’t know if I figured out what I want to be. Seventy-six percent say it was stressful. I had no gray before I transitioned.

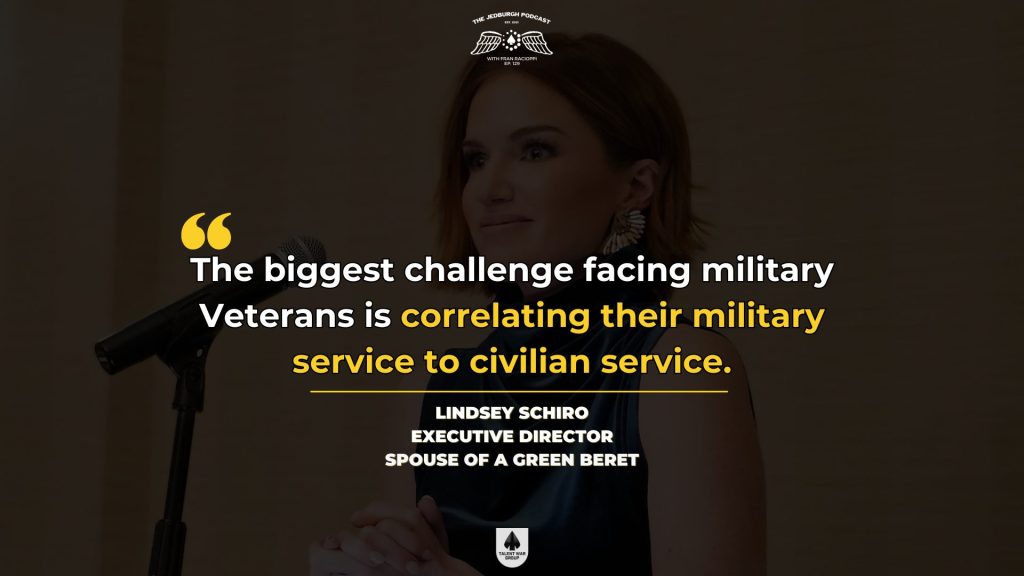

I’m also getting older but still, there’s so much stress associated with that. The mission of 51 Vets is to connect and transition veterans from elite military communities with leading business professionals. Lindsey, as you lead 51 Vets, what’s the biggest challenge facing veterans as they transition from military service to civilian life?

I would say the biggest challenge facing military veterans specifically in 51 Vets is correlating their military service to civilian service and transitioning the jargon from military service to civilian service. How are they transitioning those skills into the real world? How are they transitioning their job that they had in the military to a job in the civilian world? We help them all with that and that transitional period.

It starts with the resume, too. As you say that, I think about the resume and that process you have to go to, where it’s like, “Commanded X amount of soldiers.” It reads like your OER or NCOER and people don’t even know what that means. You do have to distill that down. How is 51 Vets filling that gap?

We do it in 1 of 3 ways. We have our city summits which we’re on now in New York City. We aim to have those three times a year. Those are meant to open our members’ apertures to different industries. We visited a private equity firm, an investment bank, a consulting firm, and different firms and organizations that are meant to open our members’ aperture.

We have those, as I said, three times per year. We also have one-on-one mentorship. Chris here is also a mentor of ours as well as a board member. We have industry experts as well as 51 Vets members who have already transitioned to help recreate the wheel. They give back and mentor 51 Vets members. We have resume writing, disability assistance, scholarship funds, and relief funds. We have a bunch of different ways that we’re helping our members out.

There are two sides to this. You said that a lot of the organization’s focus is on distilling down the veteran service into something that they can speak about and present. It’s also educating employers and getting them to understand the value that they bring. I want to talk with You Chris and Victor about your military careers. Chris, you’re an F-18 Pilot in the Marine Corps, then you worked in investment banking at Goldman Sachs and now you founded your own firm. Victor, you transitioned from the 5th Special Forces Group.

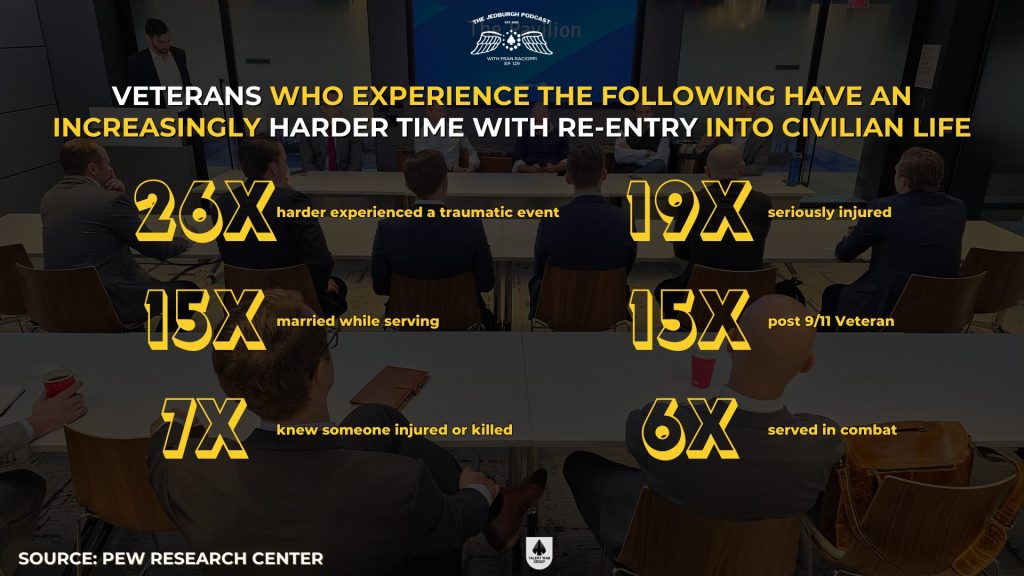

Even though it’s the 5th Group, that’s all right. You still served well, but you spent time before that in the Marines as well. Happy birthday to you, too. Now you work at Deloitte in human capital and organizational transformation in a consultancy role. There are a few more stats I want to give you. I want to turn it over but the Pew Research Center says, “Veterans who experience the following have an increasingly harder time with reentry in the civilian life.”

“Those who experienced a traumatic event, 26 times harder. Those who are seriously injured, nineteen times harder. Those who are married, fifteen times. Post 9/11 veteran, fifteen times. Served in combat, seven times. Knew someone injured or killed, six times harder.” Knowing those stats and the difficulty that you’re going to face down the road potentially. Why even serve? On Veterans Day, that’s an important question. Chris, you first. Why even go into the Marines?

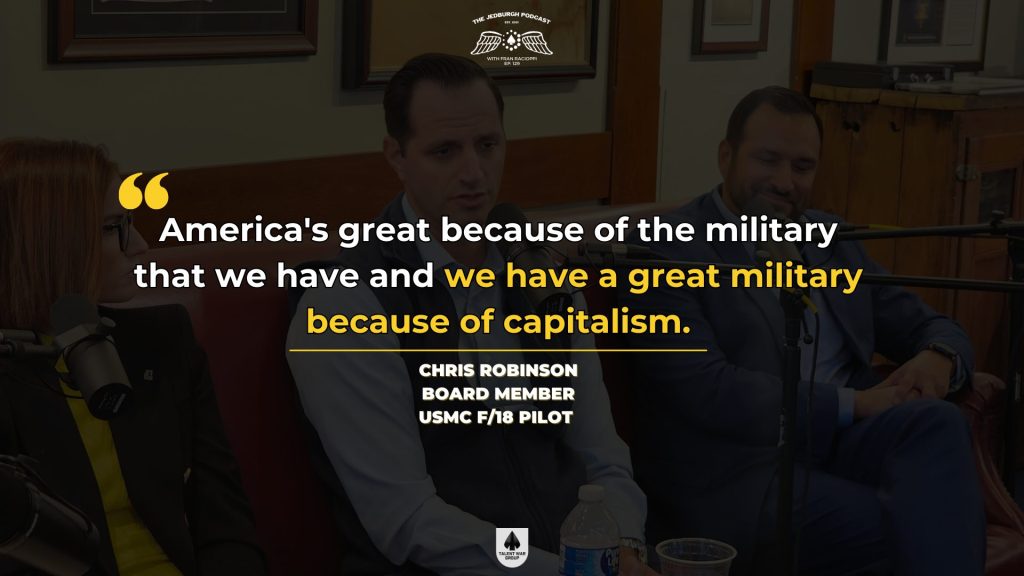

You’re making it tough by thinking about the stats that happen after service. Maybe when you first join, you’re unaware of those as potential outcomes of that life of service. For me, I was in college studying business. I had the good fortune of going to a liberal arts school. I’m taking some Political Philosophy classes. I felt the calling to serve. That manifested in me. I grew up 30 miles east of the city. Wake of 9/11, I want to serve our country.

Long Island?

I grew up on Long Island. I felt like that was something I had to do before I ever entered the world of business. Looking back, it makes a ton of sense. America is great because of the military that we have. We have a great military because of capitalism, and economic support that we can do. A lot of veterans do find themselves afterward. I may be getting ahead of what you’re asking about but I see entering entrepreneurship or capitalism as an extension of being an American, but for me, it was about giving back first before I enter the world of business.

What about you, Victor?

I was a 9/11 baby. Right after 9/11, I felt the calling to serve. For a lot of veterans, it’s being part of something greater than yourself. That’s where that purpose and that mission-driven starts. To your point about transition, that’s why it’s so tough sometimes for Veterans as we transition out because you lose that sense of purpose and identity that you did for so long, whether you’re a Marine pilot or a Green Beret. Those started with purpose.

Purpose is something that we chase. We take it for granted when we’re serving because you’re there every day. Everybody’s mission is aligned. You never question people. Certainly, we have all those people we remember. We questioned their work ethic and, “Why are you here if you don’t put in the work to want to be here every day?” Everyone’s aligned with the goal of protecting our country, building great organizations, and being the best that they can be.

You run into people who don’t feel that way. You come into the corporate sector and all of a sudden, all these things that I’ve listed here manifest themselves because people don’t share that same clarity and vision. When you were faced with the decision to get out, talk for a second about why you made that choice and how you started to approach that transition period.

I can go first, too. Being in line here, but also, sequentially, I entered the civilian force before Victor. For me, it did bring me back to one of the original things that I decided. I was going to serve our country for some time before getting back into the world of business. Throughout my military career, I did deliberate around, “Am I going to stick around for a longer period of time or not?” I did feel after some time that it was something that I could do that would also bring value to the world by being part of capitalism and entering the world of business and potentially building to bring those values that I learned as a member of service into the business community.

For me, unfortunately, 51 Vets did not yet exist. I decided to go get an MBA so I can learn a little bit more about that. Knowing that at least that transitioning path of getting the education and learning about business may open up doors for jobs, I at least had that assistance through that process. I’ve always wanted to be in business, and so that was my time to do it.

What about you, Victor?

Family. I have a son, a great kid. He got his Mom’s soul, but I have spent five years of his life with him. When I think of the future and how many more years I have before he gets kicked out and goes to college, I want more time. I’m super blessed to have fifteen different combat deployments, all these things all the time, and working with some amazing, great people. When you’re in the teams and in that special operations world, you’re juggling two families. You have to and that’s the way it is if you want to be successful and to grow these amazing teams. You’re juggling the family at home, and then the family at work. I wanted to stop juggling.

You and I were speaking at the inaugural dinner, the benefit dinner, which was amazing. Thanks so much for inviting me. It’s a great time. I get to spend time with both Victor and Chris and so many other people. Some of which I’m already communicating with 48 hours later and talking about opportunities to do things together. That was amazing. I told you, when I was staring down that tunnel of transition very much similar reasons. My daughter was 4 and I had 18 months where I had been at home and not consecutively. That was just sitting there doing the math, like, “I was here 2 weeks, then 2 weeks here. That’s a month.”

That’s hard. That’s a big toll on folks who have to make that decision. It becomes a scary time. Lindsey, you’re a spouse of a special operator. You’ve worked over the past ten years and a number of special operations-focused nonprofits, helping with transition and with a number of other causes to support them. From your perspective, what does that challenge look like? What do you see?

From transition?

When you look at your husband, as a spouse, what’s the perspective of the spouses as they have to watch, guide, coach, mentor, and help their special operator go through that transition?

My husband’s trajectory was a little different. He came in wanting to be a career Green Beret. He wanted to do the full 20 and 25. He wanted to make it his life. In 2014, he was shot in Afghanistan and his best friend was killed next to him. At that time, I was pregnant with our son that he was like, “I’m done. I’ve seen what they can do. I almost didn’t come home.” He was undeployable, so he couldn’t deploy with his team. He taught at selection for five years before he medically retired. His transition was a little different as he didn’t get to do his full career. It was cut short because of his injury then he had to pivot a lot sooner than he wanted to.

How do you then help advise a coach and say, “This is what the next step looks like?”

I was fortunate enough to work with different nonprofits. I work with the Green Beret Foundation and The Honor Foundation. I knew what transition incurred and what it was like to go through a transition. I recommended the SkillBridge Program to him. I don’t know if you’re familiar with it.

He did a DoD SkillBridge Program with the company he’s working for now and they hired him afterward. I had a leg up on that and I was able to assist him in ways that other family members would not be able to because I knew what was out there for him. SkillBridge Program is not widely known. Here at 51 Vets, we’re trying to make it more well-known to help our members and help the companies transition our members as well.

The DoD SkillBridge Program is great because you have the government who, for six months, is going to pay the salary and the costs of this person, this transitioning service member to work in your company. You talked about it at the dinner. 51 Vets is helping companies to set this program up. I’m going to email you because I’ve got two of my companies that need this now.

We’ll hook you up.

We got to get that going because honestly, I’ve had no time to fill it out. It’s on that list that you keep making like redoing every week. You’re like, “What are the things I’m going to do?” That’s been on there for a few months. I’ve got to get that done, but I fully support organizations going out and seeking out the DoD SkillBridge Program and bringing that into their organization. You can help with that.

I want to talk about character. Character sits at the core of building elite organizations because of Special Operations Forces’ truth number one. Victor is smiling because he knows what I’m going to say. People are more important than hardware. It doesn’t matter what great things you have. You have all the resources in the world, all the money and equipment. Everything we could ever ask for.

[bctt tweet=”Character sits at the core of building elite organizations.” username=”talentwargroup”]

If our people suck, our organization is going to suck. That’s the reality of it. We can have very little and have great people and achieve a lot. Special Operations is built on, “Can I take this group of twelve?” They can go do great things with 400 or 1,000 people in an area and on a mission where the guidance makes it better than when you left.

The members of 51 Vets are primarily from Special Operations units, Army, Green Berets, Rangers, Navy SEALs, Marine, Raiders, and the Aviation Community across all the different service components. Special Operations uses a specific set of selection criteria when they assess character. There are nine specifically that they use, drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, curiosity, team ability, effective intelligence, and emotional strength.

Depending on whether you’re recruiting someone to be a Green Beret, Army Ranger, MARSOC Raider, or Navy SEAL, they’re going to weigh all those things slightly differently. They’re going to say, “If you’re a Green Beret, we care about these more than if you were being selected to be a Navy SEAL.” When 51 Vets was started, why was the focus put on the Special Operations community?

It was put on the Special Operations community because there’s a different type of up-tempo that goes with Special Ops. You deploy more, and more is required of you as you mentioned. There’s a selection process and they bring more to the workforce. They bring a very specific skillset to the civilian workforce than someone from the larger Army would bring because they have gone through more deployments, have that team mentality, and have those different assets. We focus on the Special Operations community and the Aviation community because of the skills that they bring. We, as an organization, heavily vet our members before they’re even allowed in. We do a character interview. They require resumes and we announce them on a closed channel.

Where people are commenting and saying, “They’re bad and now, good.” That’s how the network works.

In the Special Operations world, the best thing you could be called is a good dude. It’s like, “Is he a good dude?” It expands upon your character as you’re talking about and that’s the conversation. When you get to the level of Green Beret or Navy SEAL, they’ve gone through all that assessment selection piece but at the end of the day, “Is he still a good dude?” That’s what’s great about our little community. It’s like everyone is vouched for.

You have focused on the financial services industry. I mentioned it to a few folks. When I first got out of the Army, my first job out was at Merrill Lynch and I struggled tremendously in trying to figure out what I was going to do. I was that guy who they tell you and he may tell your members this, “Have one conversation a day.” I was like, “Fuck that. Have three conversations a day,” because I live in Colorado. I can have a 7:00 AM conversation with somebody on the East Coast and a mid-day conversation with somebody in the center of the country. In the afternoon, I’ll have someone on the West Coast.

For months, I did that, and people from all over the place. Meanwhile, I was interviewing at Google, Microsoft, Uber, and all the tech companies. I had these great visions of all these things that I was going to go do. You go through these rounds of interviews. I made it far in a number of them. I was told that was a finalist in the number of them, but ultimately, never crossed that threshold. I never found that opportunity.

Mentors would tell me, “What do you want to do?” I’d say, “Okay.” This person works at PWC or KPMG. You go to the website and there are 1,800 open positions. The attitude is, “I could do 30 of these.” I don’t know anything about most of them, but I know that I thrive in figuring out challenges. You sit down and have a conversation with this person. They’re like, “What do you want to do? I checked out your website. There are 30 jobs. By the way, I live in Colorado, but I’m willing to move to Boston, New York, LA, Dallas, or Miami.”

Eventually, somebody who had been a 5th Group guy said, “I can’t help you.” “What do you mean?” “Every time I talk to you, there are ten more jobs that you want to do. None of them, you have any experience that you can explain how you correlate to do these things, which is okay, but you tell me you want to do them in ten different cities. If you tell me that there’s one place that you want to go and there’s one job that you want to do, I could pick up the phone now and I can call that person and help you out.”

After I hung up, “This guy’s a dick.” I have a few more of those conversations. You start to hear yourself midway through your spiel. You’re like, “I’m doing it again.” It’s quiet on the other on the other line, so you are all over the place. Getting people to focus becomes hard because you have this mindset of, “I can do anything.”

I bring this up because there’s this phrase we use in transition and talent management, “Hire for character and train for skill.” A guy by the name of Rick Nelson who’s still a very good friend of mine reached out to me. he called on LinkedIn. I avoided it for months, like, “I don’t want to go work at this. I want to be a financial advisor,” but eventually, everything failed. I reached out and I said, “I’m willing to have a conversation. Why do you want to talk to me?”

The very first thing he told me was, “The Army already selected you to be a Green Beret.” Victor, as you said, you have already passed some of the most challenging and detailed assessments that anybody in the world is asked to do. You have a demonstrated pattern of success. All I have to do is teach you how to be a financial advisor. If you put the same work ethic in, you’ll be successful.

Can you talk for a minute about the importance of that phrase, “Hire for character and train for skill?” Chris will start with you. As a mentor of the members who are coming to you and telling you, “I’m going to go to five different cities and do 50 different jobs.” What are you telling them? Also, what are you telling the companies on the other side to get them to understand, “This person might not have this direct experience, but they’re going to be valuable in your organization?”

There’s a lot there. I’m going to try to address at least a couple of those topics in a way that could be helpful. There was a conversation we had at HPS, a large credit fund. It was a veteran founder of the business speaking to us. He mentioned two things that he sees in veterans who come into whatever transition they’re doing. It’s the exposure to leadership at a young level and also their ability to make decisions and ambiguity.

He said, “What you should focus on is helping communicate those things that are transferable to the job that you’re maybe pursuing.” In addition to all the character stuff you’re talking about, that’s one way to begin the process of at least educating firms on how they can engage with the veteran community in a way they understand can make value right away.

On the other side, as we’re speaking to the veterans, that is one of the big benefits of 51 Vets where they get exposed to a bunch of the different tracks that are available to them. There are many organizations out there that support veterans. We have chosen to focus on special operators and fighter pilots for specific reasons.

One of those is they tend to seek similarly challenging career paths. Also, when they get through to the other side, ideally, they are succeeding and they can then demonstrate to the civilian world. Whether it’s in that firm or job, veterans can do this too. Now, we can potentially break down that barrier for other veterans to pursue afterward.

In our organization, we educate the veterans on the different opportunities there. We’re constantly asking the questions. First of all, you‘ve got to figure out what you don’t know. If you’re not positive where you want to be, can we start to at least remove things from the plate so you can start to isolate down? To your point, a lot of times veterans are like, “I can do anything.”

We try to hone that story in on, “It has to be authentic but you do need to give something very specific so people can help you.” That’s part of the community that we have where they can engage with folks who are in transition with them as part of their tribe. Also, those who have gone through it and our civilian counterparts and members of the advisory board that have been around successful careers for 20 and 30 years.

I want to go a little deeper on that because you said that you have this population of people who can think they can do anything and your job is to focus them. That council that I eventually had to heed to focus me in as so many do now. How do you get the transitioning veteran though to understand that this isn’t final?

Your first job out of your career in the military is probably not going to be the defining moment for the rest of your life. Is it important? Yes, let’s not be wrong. We go to the military like you talked about your husband. I had entered with the same thought process. I’m going to be here for a career of 20 or 30 years. We inherently approach the transition with that same mindset, “I’ve got to get this right now. If I don’t, I’m screwed for the rest of my life.” How do you get them to understand that sometimes good enough is good enough?

Real quick, I can try to address that. You’re spot on. You can point to case studies. Look ahead to these different people that you look up to and examine their path. Many of them meander quite a bit around than just general advice that try to give or all things being equal and optionality. If at least you have the awareness to recognize that you don’t know everything. Expose yourself and get into action. Start moving.

Another little formula, make sure you can learn, earn, and collect a merit badge along the way. Meaning you’re going to learn a new skill that maybe helps you get to where you want to go. It’s time to make money. We’re not doing this philanthropically and collecting a merit badge. A lot of times, there’s a risk factor if you go down a path that the civilian world doesn’t recognize. There is some value to cutting your teeth. I chose to do it because I thought it was valuable to go to a firm where people would recognize what that career path would provide to somebody as a skill level and technical ability as a baseline.

Another little formula, make sure you can learn, earn, and collect a merit badge along the way. Meaning you’re going to learn a new skill that maybe helps you get to where you want to go. It’s time to make money. We’re not doing this philanthropically and collecting a merit badge. A lot of times, there’s a risk factor if you go down a path that the civilian world doesn’t recognize. There is some value to cutting your teeth. I chose to do it because I thought it was valuable to go to a firm where people would recognize what that career path would provide to somebody as a skill level and technical ability as a baseline.

[bctt tweet=”Make sure you can learn, earn, and collect a merit badge along the way.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I went to Goldman as a banker and fortunately or unfortunately, I have that now as something that people can look to say, “Chris did these things in the military,” but I know what banking is. It makes it a little bit easier for conversation to have and it does potentially open doors. That’s part of the advice I try to give. If you’re not positive, then pick something that will at least open more doors for you.

Victor, you’re a year out from your transition. You’re in this 1-meter knife fight. Talk about that experience from the perspective that you have as you sit here in this first job out of your military experience.

The transition is a beast because anytime you do something for 20 years or 10 years, it’s going to be difficult.

The longer you’re in, the harder it is.

For the Special Operations community, we go back to that juggling of families. You’re all in and you have to be because lives are on the line. When you do that transition, to your point, we could do anything and we did. One mission we’re kicking indoors and shooting bad guys. Another mission, we’re building governments. It’s so wide.

Possibly on the same day.

What I recommend to folks as a transition now and what I wish I started earlier on was to get surgical on what you want to do because like you said, you could do anything.

Separate those out. Want to do verses can do.

I put the can in folks like us. You can do it. What you want to do is the difficult part like consulting. There are different types of consultants, finance consulting, business consulting, and management. When I was transitioning to 51 Veterans, I said, “We have a consulting track.” I talked to a whole bunch of consultants from all over the Big Four, and MBBs.

A question always came back to, “What do you want to do? Do you want to be in tech or finance? Do you want to focus on the industry?” That would be the point, start one. As many years out, if I joined the military, I would start thinking about it now. What do you want to do? That was my biggest challenge on the journey. As soon as I found that, for me, it’s human capital business transformation. That’s what I love. I love working with people and figuring out problems. That’s where I got to focus. Once I focused on there, everything else came along with it.

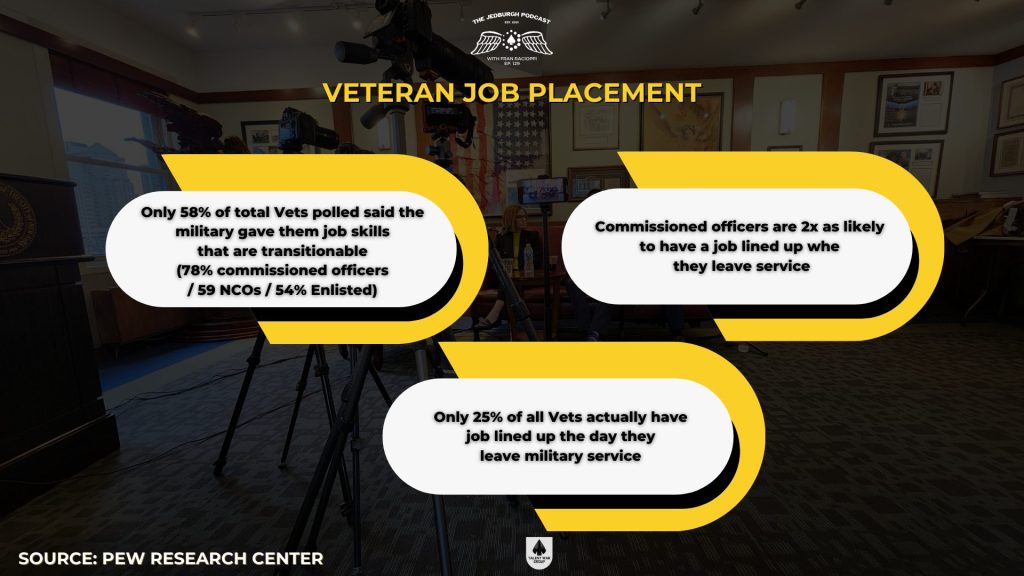

There are a few more stats from Pew Research, 58% of veterans polled said the military gave them job skills that are transitionable. Think about that. Forty-two percent of people who are coming out don’t think that they have transitional skills. I want to dig into that in a second. Commissioned officers are two times as likely to have a job lined up when they leave service but only 25% of veterans have a job lined up on the day that they transition out.

Lindsey, when you assess candidates and members to come in, you’re looking at their character, their resume, and understanding the background that they have. I found that number to be staggering. There is 42% of veterans who think that they didn’t learn anything in the military that they can bring to a civilian organization. That’s crazy.

I believe it. We see it. Twice a year, we do an all-call. We have all of our members and we ask them what they want from 51 Vets for the next year. How can we better serve them? A lot of them are like, “How do I transfer my skills? I was in the military for 10 years, 15 years, or 20 years. I commanded teams. I did X, Y, and Z, but what does that mean in investment banking? How do I go be an investment banker now?” We’re helping them see that their skills are relevant. That what they did in the military was relevant to what they’re going to be doing in the civilian world.

What about you, folks? What do you tell them? How do you break that down?

It’s pretty funny because there’s a bit of a bifurcation. Some people overestimate the value they can bring. Maybe pressing company included to some degree and there are those that unfortunately feel that way.

I feel like I’ve done both to myself.

It goes back and forth. It’s hard and that is another feature of this organization. We’re centering force. We bring those together like, “Don’t be so extreme to expect like you’re going to go join a private equity investment deal team on day one of being a civilian.

They’re out there.

They do and we try to like, “Come over here and look at what it was more typical to see,” as far as a path. There are others like you’re suggesting that don’t know. Hopefully, we can do a good job explaining to them like, “These are the attributes of character that firms do value.” The good firms talk about it. They have their cultures and their mission, vision, and values on their websites and their publications.

It’s funny when I was interviewing at Goldman. They have 14 value statements and they align those 14 like the Marine Corps as well. They at least are making an attempt to drive culture and take care of their people first. There are firms out there that do that. Ideally, we can connect the dots between veterans and show them that the civilian world does value very similar things. Maybe they don’t do it as well as the military, but they’re trying.

What about you, Victor?

For Green Berets, Navy SEALs, and Raiders, you’re working at such a high level all the time and you get to a pinnacle. You’re the 1% of the 1%. When you do that transition, there’s no Green Beret or Navy SEAL civilian person. We have to check our egos. We have to remember how it was when we started, when we went into selection. None of us were like, “We’re going to make this. This is it.” Everybody was scared shitless and like, “Can I get through this?”

When you do the transition, you have to take yourself back to that point. It’s like, “I’m going to be humble enough to know I don’t know,” but things like 51 Vets, what makes it great is I know people to go talk to you that are in this space that can help me understand the lexicon. To Lindsey’s point, a big problem for us is the transitional terminology of what we did. We joked about it. I may be doing a stakeholder analysis for my firm. Years ago, I called it a feasibility assessment in our world. Understanding where those overlaps are is important starting with the veteran understanding where he wants to be.

It’s important to understand that it’s a journey. Chris, you said, “Can you do something when you get out?” Maybe it’s not where you want to be but it takes you 1 step or 1/2 a step there. When I made my decision to go to Merrill Lynch, I had an idea that this isn’t necessarily what I want to do, but will I learn something? I was in business school. Go to a financial institution. I went to NYU. You studied financing there. I didn’t take organizational design and leadership because I spent thirteen years in Special Forces. I took Finance because I didn’t know anything about it.

I was interviewing with Google and they’re like, “When you manage a balance sheet,” and I’m like, “What’s a balance sheet?” I had to learn those skills, but that’s a journey. When you can get anything, go and do that thing. It puts a great company on your resume. It gives you that next set of skills. You also don’t know how those experiences are going to shape you and come back later on.

Before we started, people will have to look at the behind-the-scenes footage. You were commenting that we have all these cameras and microphones. This is a crazy production to me. I feel like we have so much further to go. I go on the entrepreneur’s journey every day. We suck in the morning, we’re great by noon, then we suck again by the afternoon.

We’re here because I mentioned Rick Nelson and because of the experiences and the people that I met in my eighteen months at Merrill Lynch, who three years later down the road, after I’d gone on to be the Chief Security Officer at Snapchat, run a cannabis company. When I started this show after all of that, it was him and the relationships that I built with Jersey Mike’s CEO Peter Cancro, who I called up and asked for advice. He said, “I’ll be one of your first guests. Not only that, but we’re going to give you the seed that you need to sponsor you to build your dream.” It would have never happened if I said, “I don’t want to go do this thing.”

Embracing that journey, it’s important to get people to understand that it’s not final. You can pivot and change. I’ve been out six years and worked in finance, ran security, ran a crazy industry selling drugs, depending on what state you’re in, and then started my own business where we’re doing a variety of different things. All the while, when I started my own business, the actual thing that I wanted to do, because all of those were things that I could do, is this right here. That’s the only thing I want to do.

I was talking with the veteran walking down the street in New York, who was like, “I don’t know what I want to do. I find private equity interesting. I find investment banking interesting.” I said, “You don’t have to decide. You can pivot.” If you go into investment banking and you fucking hate investment banking, then go to private equity.

I said, “Personally, I’m a civilian and I’ve had a couple of jobs in the last seven years. I’m pivoting.” It’s understanding the mindset that you’re not stuck in that. It’s not signing on the dotted line like you did with the military where you’re in a contract, you reenlist, and you’re there for the next 5 to 8 years. You have the ability to move, pivot, and do what you want to do.

You’re a civilian now. You get a choice. You get way more choices. I said 76% of veterans say that transition is going to be stressful. I’ve been very fortunate on the show to have been embraced by the CrossFit community where we’ve talked a lot about doing hard things. Victor, you mentioned something about how you’ve been selected. You’ve done the hardest of the hard. Transition is probably the hardest of the hard but I feel like when we’re looking at transition, we take all those experiences that we had and we think, “This is going to be easy. I did the hard stuff.”

In reality, I would argue that doing what you want to do is probably going to be the biggest challenge that you have. I know it is for me. As I mentioned, doing this is what I want to do. I want to do this and yet, I keep being told by Fox News, CNN, MSNBC, and Spectrum that I don’t have the experience to be a network news anchor. I asked the question, “What do I have to do? Do I need to be an intern again? I was one twenty years ago. I’m willing to do it.” They’re like, “You’re 43.” I’m like, “I don’t care. What do you want me to do? Tell me what you want me to do. I’m willing to go do it and start at the beginning like you said.” I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that.

I agree. For veterans in our community, you run it. Have you ever heard of Art Finch? He was our psychologist at Special Operations. You should get him on the show. He put it together and when he was doing an assessment of operators, he would look at verbal intelligence and performance intelligence. Verbal very much your what you learned in school and what you’re exposed to.

Your performance intelligence is how fast you process information. Our community is record high on the process information. Why? As a good example to this, when the shit hits the fan and you’re in a gunfight or in this crazy environment, how does our radio sound? Our radios sound the coolest comments. Everyone’s talking calmly. It doesn’t move with the event and that’s because of the way we function.

Going back to verbal intelligence, when we’re transitioning out, going to the lexicon or terminology translation, we can process this information and do all these amazing things but it’s getting in front of the person and an interview as an example and having that verbal intelligence to explain exactly how you do it where we need to do better as an organization as a department defense, honestly, like Taps.

Taps wasn’t made for guys like us. It wasn’t made for a twenty-year-old person or a special operator. It’s made for the awesome kid who came in at 18 and left at 22. When we look at how we get after the problem, we need to help focus on what these special operators can do, and then get them in front of the people. On the teams, we always say, “Proximity to the problem. Proximity to decision-makers. That’s how we make influence. That’s how we get things done.” This is what 51 Vets is doing. We’re breaking down the walls and we’re giving you the proximity to have the conversations.

Too many of our brothers and sisters from service lose the transition battle. Veterans are at a 57% higher risk of dying by suicide than those who never serve. We’re still hovering about 20 to 22 veterans a day who take their own life. I’m involved with an organization called SailAhead on Long Island, where we take veterans and teach them how to sail. Teach them new skills and get them off the land. There’s healing power in the water.

[bctt tweet=”Too many of our brothers and sisters from service lose the transition battle.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I spoke at our annual event and the very first thing I said was, “Every year, I hope I don’t have to come to this event because if I have to come to this event, it means that too many veterans are taking their own life.” That number is not going down. Over 7,000 service members were killed in the global war on terror but since 9/11, over 30,000 have taken their own life. One of the Navy SEALs who spoke said that he knows more SEALs who’ve died by suicide than died in combat.

Zach Walters. He’s on our board as well.

That’s a profound statement. I thought about the Green Berets who I know. Even the fact that primarily the 3rd Group, 5th Group, and 10th Group took the brunt of the global war on terror, I think about those that I lost in service. That number holds true for me, too that I know more who’ve lost their battle after than in combat.

Job satisfaction and job placement become, I believe, critical to that vision. We started that conversation by talking about vision, impact, mission, why we are here, and what we are doing. The biggest struggle that we hear from those who have mental health challenges when we leave is losing that identity, community, vision, and purpose.

In your work with the organization, as you come with your Cities Summit to bring people together and build that community, why is that so important for 51 Vets to build the community and this network to not only get special operators roles in companies that provide impact but also to give them a network of people that they can pick up the phone and call because they’re going through the exact same thing?

We’re saving lives here. We are creating a sense of community and purpose. We have a close Slack channel where all of our members can chat with each other. We have city summits. We have a presence in Nashville, Dallas, Los Angeles, Wharton, and Philadelphia. They can reach out to 51 Vets members that are right there in their city. We have these city summits that show them the purpose of what’s out there, post-transition. It opens their aperture and things.

We have mentors who are available to them who are veterans, saying, “I did it. I transitioned well and you can too.” It’s the whole premise of making this community better and more supported and letting our employers know that the way they give back to this community is by hiring them for internships, jobs, and things like that, and doing so gives our members a sense of purpose.

Lindsey said it greatly. The community aspect can be very lonely when you transition and you don’t have that community. In the military, there are usually onboarding classes. You’ve got a group of peers. You’ve got people now that you know that you can lean on forward and behind you. In the civilian world, you’re pretty different. At least, many of us feel that way, initially. Organizations like this do a good job of bringing you back into your tribe.

In the Aviation world, we have the ready room like cowboy time. Hang around, and share stories and learnings. It’s a practical application of like, “This mission, here’s what’s going to happen.” It’s that knowledge sharing. Without organizations like 51 Vets building that for the civilian transition, it doesn’t exist. By having that safe space and that place to go where your people are, you feel a little bit closer to what it felt like before.

It’s never going to be replicated fully but our goal is to continue to do that for folks and give them their tribe. Give them that support network and we’re there for them emotionally and physically in the job world. All these different ways that matter to people and to our veterans, that’s where we’re there to support.

The stats hurt. That’s tough because like you, the folks who took their life, those hurt way more than the folks you lost on the battlefield. It’s not even close. It’s way more because we feel like you could do more. When we’re talking about transition, we’re such mission-driven and results-oriented people in this community. That’s a purpose part and when you get a job, there you go.

The stats hurt. That’s tough because like you, the folks who took their life, those hurt way more than the folks you lost on the battlefield. It’s not even close. It’s way more because we feel like you could do more. When we’re talking about transition, we’re such mission-driven and results-oriented people in this community. That’s a purpose part and when you get a job, there you go.

I used to do this and now I’m doing this. That helps that purpose part directly. Let’s say I’m talking about saving lives. It does because it gives you the ability to focus on something but at the same time, to his point, it gives you the community to feel like it was. You joke around a little bit and they understand what you’ve done.

We’re closing out 2023. That means you have a new year ahead of you to start to plan for and think about. What’s the focus of the organization going into 2024?

Supporting our members more and doing more for them. We’re going to be focusing on, as I said, those transitional skills. We’re getting resume reviewers, writers, and people who specialize in resumes to help come in and assist our members in writing their resumes. We’re going to be VA Benefits Specialists and talk about VA benefits and make sure everybody’s set up with that when they go through that transition period.

More city summits and in different cities. Next year, we’ll in be Chicago, Boston, and probably someplace in Dallas. Another dinner in Boston in 2024 around Veterans Day. We’re continuing to grow. We have 300 members and we’re just getting started. The more members we have, the more we’re able to offer the members that are in our group. This 2022 has been a lifting-off point for us and we have a lot of growth to do.

Final question, as we close out, the Jedburghs of World War II had to do three things every day to be successful. They had to be able to shoot, move in, and communicate. You guys are smiling because you heard this before. If they did these three things as core tasks, foundations if you will, skills that they could execute without thinking about it, then their focus and their energy could be on more complex challenges that came their way every day, primarily arming the French Resistance and combating the Germans from reinforcing the beaches in Normandy. What are the three things that you each do each day to set the conditions for success in your world?

I wake up. I have three small children. Every day, I look at the success of how they view me. I want them to have a mother that they’re proud of. Not a mother that had struggled or done anything of that nature. I look at success every day as if I was able to be a good mother and a good employee. If I was hoping, doing my work for 51 Vets, growing the trajectory of the organization, helping our members, growing our talent pool, and at the same time, taking care of my children, being present for them in their lives, and being a good mother, then that’s a good day for me.

I can distill that to three.

That’s technically two but I will say wake up with the third.

I’ve never had anybody give that answer, so that’s awesome. Chris, you live by checklists.

I know. It’s funny. I’m not prepared to give you the definitive three, but I’ll do my best to talk about what are our three important ones at least.

That’s why I don’t let you prepare.

It’s good. Keep us extemporaneous. I’m going to take maybe a step further back in time to what Lindsey just said, which is to focus on sleep. Take care of your physical welfare. Sleep is a critical component of that. Aviators are soft. We’ve got our footrest. It starts in my blood but came to appreciate that after many all-nighters in the world of banking to appreciate the value that that does.

Looking out for physical welfare begins with sleep for me. Throughout the day, there’s a checklist piece, but it’s all about making decisions to maximize your return on time, to steal a quote from someone but thinking through, “What’s the best use of my time for the day?” That might be planning your calendar whether it’s your to-do list or being very deliberate about how you spend your time.

The last one is there are many ways to describe this but thinking long term, whether that is treating others how you want to be treated, being long-term greedy, or keeping your eyes on your horizon and working hard and playing nice. There are a lot of things to capture. Remember, life is not a one-round game. When you think about games, it’s a repeat game that you’re participating in for the long term. Always keep in mind that in everything you do reputationally, there are long-term impacts. You might not be thinking through and don’t overcomplicate but just keep your eyes on the horizon and think long term.

The last one is there are many ways to describe this but thinking long term, whether that is treating others how you want to be treated, being long-term greedy, or keeping your eyes on your horizon and working hard and playing nice. There are a lot of things to capture. Remember, life is not a one-round game. When you think about games, it’s a repeat game that you’re participating in for the long term. Always keep in mind that in everything you do reputationally, there are long-term impacts. You might not be thinking through and don’t overcomplicate but just keep your eyes on the horizon and think long term.

[bctt tweet=”Don’t overcomplicate things. Just keep your eyes and horizon and think long term.” username=”talentwargroup”]

I’m going to tell you say anything. We’ve had variations of what you’ve thrown out here, but not in this way. I do appreciate the fact and Victor, you appreciate this too. We think about our day in terms of the work first. You think of your day in terms of the crew rest first. Now I’m inside of the mind of a pilot.

You got to set the conditions for success. You ask me the conditions for success. That is the condition.

I like it. We’re thinking about this all wrong.

That’s why I wish I should have been a pilot.

I’ll take this a different way. I have a mantra that I’ve lived for a very long time, whether I was on the teams, supporting and leading, being a team member, or talking to my boys. The three things each of us can control are faith, attitude, and effort. Faith starts with believing in something bigger than yourself, and remembering that you’re not the center of the universe.

[bctt tweet=”There are three things each of us can control: faith, attitude, and effort.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Attitude is your emotions and how you can control them. It’s the attitude you bring to whatever you’re doing. If I’m sweeping floors versus doing something I love, effort is all about what you can provide to it. If you’re going to sweet floors, be the best damn sweeper ever. Those are the things that you can control. I try to live up to that.

I love how you define those, faith, attitude, and effort.

There’s so much in this world and I got this from the teams. When you’re in a complex environment where every move you make is changing the in-state because it’s a three-dimensional chess. Complicated problems are easy. I love complicated problems. You figure out the process and you’ll get to an end.

Our background speaks awesome to our folks like, “I’ve watched these guys do some amazing things in the weirdest complex environments.” They’re having to make 3 to 4 moves to make the in-state whatever they want to make the in-state. What that does though is it teaches you, “There’s so much that I can’t control. That helps me to find what I can control and that takes me back to the faith, attitude, and effort.”

We’re wrapping up here in the city. Everyone’s going to go back and take these connections and the network that has been built here. You had twenty members throughout the week. It’s a phenomenal number to start again in front of so many organizations. As I said before, I couldn’t be more appreciative of you inviting me into the community and giving me the opportunity to meet everybody and sit down with you guys.

Veterans do great things. Veterans Day is coming. We’re going to be here for the parade. We will be back in the Dodge, WC-51 at the end of the red carpet down there on 5th Ave. When you watch what veterans are capable of, not only in the military but in the civilian world, I believe that their service and what our veterans have given to our country while they wear uniforms, and I would argue more importantly after, is part of our national culture.

I’ve done a lot of work with the Army this year. I’m very fortunate that they’ve embraced our platform partnership. We sit in a spot where recruiting across all service components is at a historic low, especially in the Army. That is important not only for our National Defense, but that is more important because that is an entire generation of leaders that are not being developed for society in 5 years, 10 years, and 20 years from now. What veterans bring to companies, hometowns, and families can’t be quantified. That’s what America is.

I was asked on a show I was on, what book I would recommend to somebody to read. If I had one book, it would be 1776 by David McCullough because it tells the story of America. It tells the story subliminally of the culture of America that is defined by people who are willing to serve their nation who knew nothing about military service, stood up, created a country, fought for it, and then went back to their lives with that experience and created the greatest country on Earth and in the history of the world.

What you’re doing in 51 Vets is preparing those leaders to become the next greatest generation. It’s out there that lives in all of us. We’ve got to pull it out. We’ve got to get our country out of this divide that we’re in because the greatest days of this nation are ahead of us. It starts with the work that you’re doing, so thank you so much.

Thank you so much for having us and for coming to the dinner. We appreciate you being there.

Enjoy the rest of New York.

Thank you so much.

Thanks again. This has been great.