Over the last seven years Diane Conn has taken tens of thousands of pictures of people holding hands. As the COVID-19 pandemic broke apart so much of the fiber of our community she was motivated to put her pictures into a book, called Holding Hands, showing us all just how important holding hands actually is in our lives.

Fran Racioppi sits down with Diane to discuss the impact the loss of her mother to suicide had on her. She shared her battles with depression and a severe concussion that changed her outlook on life. And she talked about the film industry, her late husband, Mace, and how she captures pictures of total strangers holding hands in New York City.

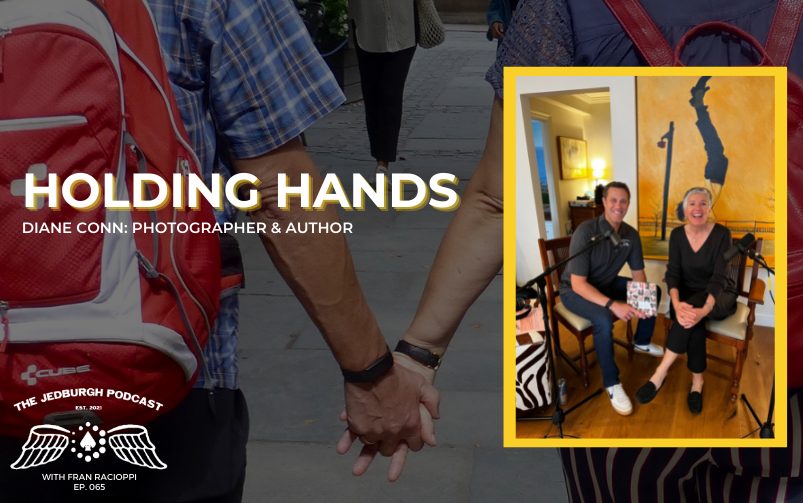

Take a listen to our conversation then check out our YouTube, Instagram, Twitter and LinkedIn to Fran and Diane searching for the perfect shot.

—

DIANE M. CONN has been photographing both relatives and strangers ever since she took her first Kodak Instamatic 124 on family vacations as a child. And yet it was a candid picture that someone took of her—properly speaking, of her and her new husband on their wedding day—that first helped Diane realize just how fascinating it is to watch people holding hands. This discovery led her on a years-long project to photograph people in all life stages…in all walks of life and in many parts of the world…all united by the simple act of holding hands. Her first photo book Holding Hands is the result of that adventure. Beyond photography and taking life one day at a time, Diane’s greatest joy may well be sitting in the original Eames chairs she inherited and reading her way through classics. When she’s not taking photographs of people holding hands (and she rarely stops), Diane lives in New York and Los Angeles, where she seeks out walking routes that allow her to imagine she’s strolling down a country lane.

DIANE M. CONN has been photographing both relatives and strangers ever since she took her first Kodak Instamatic 124 on family vacations as a child. And yet it was a candid picture that someone took of her—properly speaking, of her and her new husband on their wedding day—that first helped Diane realize just how fascinating it is to watch people holding hands. This discovery led her on a years-long project to photograph people in all life stages…in all walks of life and in many parts of the world…all united by the simple act of holding hands. Her first photo book Holding Hands is the result of that adventure. Beyond photography and taking life one day at a time, Diane’s greatest joy may well be sitting in the original Eames chairs she inherited and reading her way through classics. When she’s not taking photographs of people holding hands (and she rarely stops), Diane lives in New York and Los Angeles, where she seeks out walking routes that allow her to imagine she’s strolling down a country lane.

Holding hands is the ultimate connection and bond between two people. As kids, we hold hands with our parents. As adults, we hold hands with our friends, family and significant others. When it’s time to leave this world, we reach out one more time to hold someone’s hand and create a physical connection. Have that bond.My guest in this episode is Diane Conn, an expert in connection and holding hands. Over the last few years, Diane has taken tens of thousands of pictures of people holding hands and creating a connection with each other. As the COVID-19 pandemic broke apart so much of the fiber of our community, she was motivated to put her pictures into a book, showing us all how important holding hands is in our lives and community. I was fascinated by Diane’s perspective. I asked to spend the day with her on the Upper East Side of Manhattan.We broke down her book, Holding Hands, into three parts that she follows the evolution of our relationships through childhood, love and togetherness. She also shared with me the impact on a connection that the loss of her mother to suicide had on her. She shared her battles with depression and how a severe concussion changed her outlook on life. She talked about the film industry, her late husband and what it was like to produce the Tom Clancy films when Harrison Ford was Jack Ryan. Diane’s energy and passion for connection were contagious. There was no way I could leave New York without seeing firsthand how she captured pictures of total strangers holding hands. Take a read on our conversation and then check us out on YouTube, Instagram, LinkedIn or Twitter to see me chasing Diane up and down less in Tenth Avenue, trying to capture the perfect shot.

—

Diane, welcome to The Jedburgh Podcast.

Thank you.

Fran and Diane Conn on the Upper East Side

Thank you so much for welcoming us to your home. We’re on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. I appreciate you taking the time to spend with us.

Let’s start with the theory behind the book. I’m going to go bold off the top and combine two of your quotes. I thought they were impactful and set the conditions for what this is. “Connection is the beginning of everything. The touching of hands is a silent sensation, the ultimate expression of what it means to be human.” Can you define connection in your words?

In the context of the book, connection is a physical touching of, in this case, hands but it could be almost anything. If you watch people in conversation together, whether it’s at breakfast or lunch in a social conversation, you’ll see people often reach out and touch somebody’s arm or hand to make a point or an emphasis. That is a very old brain tendency to reach out and touch to be connected with something.

In the thousands of photos I’ve taken of people holding hands, I feel comforted looking at the photos but I also noticed that in every case, there’s not one case where people just kept on walking for blocks and never let go. People don’t hold hands for long. It could be 1, 2 or 10 seconds. Sometimes before I can even pull up the camera to take the shot, they’ve let go.

[bctt tweet=”Holding hands is great for the body. It gives you oxytocin and lowers anxiety and blood pressure.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Why do you think that?

I watch it because sometimes it’s to turn and look at a menu, fish in a pocket, answer a phone, fix their hair or because somebody is walking towards them. It’s endless. I don’t usually see them just walking along and dropping their hands for no reason. There seems to be that thing that happens in the brain where nobody can focus on anything for much where they get distracted, even from the holding hands and they go off and do something else.

“People don’t hold hands for long…There’s not one case where people just kept on walking for blocks and blocks and never let go.”

You told me when we spoke that there are 200,000 plus pictures that you’ve taken and 10,000 or 11,000 that are in the unique phase. The book is a compilation of photos that you’ve taken on the streets of the world. You called it, “The intimacy of connection always moved me.” You started taking these pictures many years ago. Why photo?

I had been interested in photography forever. I got my first camera when I was in high school, which was a big deal in those days. There were no phone cameras. I found my old photo albums from high school and before. I remembered that I was the only person who had a camera. I got some photos of the family and my parents when I was young, which a lot of people don’t have. I liked documenting things. I’ve always taken pictures. I was the person in the group who would say, “Let’s take a group photo.” That’s how it started.

All of your photos are taken from behind the subjects. How come?

I don’t want to look at their faces and I don’t want to see the front of them. A) There’s no privacy. B) They would see me and they wouldn’t be the same as they would be if they were spontaneous. C) There’s something about taking a photo from the back that allows me and the viewer to focus on holding hands.

“I don’t want to look at their faces and I don’t want to see the front of them.”

If you think about the back of a human, there’s not a whole lot going on. It’s the back of their head. It’s their shoulders and back. If they’re holding hands, that’s the one thing going on. Otherwise, it’s a button, legs and feet normally. I thought, “That’s interesting.” That connection jumps out when you look at somebody from the back end and it doesn’t when you look at them from the front.

Have you been caught?

Once up in Harlem. I was walking behind this group of people and two of them were holding hands. I got a little too close, which can be very close. I can get right behind people. One of the guys in the group turned around and said, “She’s taking your picture.” I stared at my phone and pretended I was looking something up and crossed the street. That’s the only time.

What makes for a good, genuine handhold? I asked that question because it’s almost followed by a secondary question. Are there photos of people holding hands that you won’t take because it’s not genuine? Have you got to the point where you can look and assess, “That’s genuine or fake?”

I can’t tell the difference. There are famous stories. I won’t name this couple that was walking along holding hands one night. Two days later, they filed for divorce. It doesn’t necessarily indicate anything but it is interesting because if you look at the photos in the book, you’ll see that people hold hands in a myriad of ways. There’s the full class, linked fingered, one-finger and thumb handholds.

I was walking behind a couple and took a shot but it’s probably too blurry. They were two guys walking along holding pinkies, which I hadn’t seen before. Sometimes there are unique handholds that you can’t even imagine with backward or straight hands that somebody is holding. I figured any way to hold hands is good because the person is getting that oxytocin, which lowers anxiety, pain, blood pressure and heart rate. It’s great for the system.

“Sometimes there are unique hand holds that you can’t even imagine.”

I do want to ask you about the science behind it a little bit. Can you expand on that and talk about why holding hands is so important for that connection? When does it affect you and your emotion? How do you feel at that moment? Why is that different from a hug or sitting next to somebody?

On a scientific level, it’s different because there are so many nerves and connections in the hand. It’s incredibly sensitive, especially the fingertips. People notice when they’re holding hands. I can remember the first time I held hands with my late husband. Probably with most of the men I held hands with, I can remember the first time because it’s a big deal, especially when you’re young.

Especially for guys, if you think about holding hands. For sure, when you’re younger, there’s this stigma behind it like, “I can’t hold hands. That looks weak. My friends will laugh at me. Someone might think I liked them if I hold hands.” What are your thoughts on the stigma that’s behind that?

That might help explain to me why not many people in their late teens and twenties that I could find were holding hands. I’m serious. Once you look through there, there’s this great young couple in Paris. There’s a photo in the book. They’re in Paris holding hands. It’s rare. I often look for teens holding hands and did not find it at all.

I went through the whole book. My son was looking at it with me and pointing. When you think about holding hands and the effect that it has on you, it is this progression through life. You told me that you never set out to write or create this book out of your pictures but the COVID-19 pandemic almost proved disconnection with people, which then motivated you to say, “I have these pictures of connection, community and relationship that I can put out to the world.” Can you explain why you were moved to do that because of the disconnection created by the COVID-19 pandemic?

Many people talked about they wanted to hold or touch somebody’s hand during COVID. I remember a grandma telling me that she wasn’t allowed to see her grandkids but she got so desperate after five months. They all had masks on. She loved the kids but she wanted to see her grandkids. She had them bring over the grandkids. She threw sheets over them and hugged them, hopefully through the sheets, which I thought was brilliant because it gave her the sensation of hugging them. She wasn’t holding their hands but she was hugging them. That in itself was a way of connecting with them. That hunger for connection has driven humans forever.

“That hunger for connection has driven humans forever.”

When you put all these photos together, I thought it was fascinating that some of the things I didn’t think about until you talked about it were how you organize these in some logical manner that’s going to make sense. What you settled on was to tell the story of connection, community and relationships through handholding in an almost life’s chronological order, starting from childhood, moving through adulthood and then into the golden years. You named those three sections. Holding hands is childhood, love and togetherness.

I want to talk about each one of these sections but if you will go with me on this, I would love to talk about your life because you have had a very unique life. The path that you’ve gone on has varied in so many ways. It’s fascinating if we could talk about how connections and relationships change through the course of your life, as we talk about you, where you come from and the journey that you’ve been on.

The first chapter is Holding Hands Is Childhood. For you, it started in a small town in Quebec. You are 1 of 5 children. Your parents instilled in you and your siblings this sense that you would be each other’s best friends. How did growing up as 1 of 5 set the early conditions of life to make relationships and connections such an important factor in your upbringing?

[bctt tweet=”Holding hands is when people first discover adult love.” username=”talentwargroup”]

The first thing that comes to mind visually, which might sound odd, is we played together all the time. We had a cottage on a lake. I’m not going to say a country house because it was a rustic cottage that my engineer father built on a lake. We had boats and a dock. We didn’t know the neighbors because everybody came from different areas. The neighbors on one side didn’t have any kids and neither did the neighbors on the other. We just played among ourselves. My brother, who is eight years older than me, used to wake us up on Sunday mornings to play cars.

The way you play cars is you go in the living room. On the way, you detour through the kitchen and get a saucepan lid for your steering wheel and whatever you can find to be your ancillary items in the car. You go into the living room, sit on the couch or chair, take off the cushion and put it on top of you to make it like you’re in the car. You’ve got your steering wheel saucepan lid and ancillary items. That is a wonderful memory for me.

It helps that the ancillary item makes noise so it could be a horn and there, we are playing in the living room. I don’t know how long was that. Maybe it was 20 minutes or 2 hours but it’s such a happy memory. Nobody fought. We weren’t a fighting family but it was one of those ways we connected and we’re together. We had China animals like dogs and cats and horses so we used to play China. That’s what we said, “Do you want to play China’s?” We bring all the China and the dog does this and the cat. It’s a typical children’s play but it stayed with me because it was so simple.

That’s not a huge spread, either. It’s interesting because my kids fight and argue. I looked at them. They’ll start with the pushing. I say, “I don’t understand. You’re in different stages of your life,” yet they know how to interact with each other, even though they’re different. With that connection that they have, my son knows, “This is my sister. It’s not my parents or someone else.” He has this close, tight relationship. Every day, he’ll come home from daycare. The first thing he does is run inside and is like, “Where are you?” He tries to play with her. It’s fascinating how that starts that young. It doesn’t matter that spread.

Although it may be a little harder for her to want to play with him, he’s always going to want to play with her.

It ebbs and flows. If she’s not focused on her phone or trying to watch something on her computer, then she’s all about it. If somebody is texting her, then she couldn’t be bothered. He’s a nuisance. It goes back and forth. Can I ask you about your mom? Your mother died by suicide when you were a teenager. You said, “I still remember the feeling of holding my mother’s hand. It was strong and warm, never cold.” How did that loss of connection with your mother affect you?

It was devastating. It threw my life into another dimension because it never occurred to me that I wouldn’t have two parents and a mother who bore us who could choose not to live. I didn’t know anything about suicide or anybody else who’d been through this. Nobody wrote or talked about it. I couldn’t focus on anything else.

It was all I thought of all day, every day. “My mother killed herself. Why did my mother kill herself? What happened? Why didn’t I stop her? Why didn’t I call?” I can’t emphasize it but it’s all the time. In my head, I spent the next 25 years trying to save her and figure out how to rewind time. If my mother could die by suicide, how could there be a God? I was praying to God, who I didn’t believe in, “Turn the clock back. Make it be the day or the week before. Don’t make this happen.”

“I spent, in my head, the next 25 years trying to save her. Trying to figure out how to rewind time.”

When I think of my twenties, I think of blackness. I wanted to die. Until I was 30, I kept any pill that any doctor ever prescribed to me because that’s what happened. I’d go and see a doctor. Nobody asked me what I felt or how it was. They just prescribed stuff for me and I didn’t want to take it. I stuck it in a shoe box. By the time I turned 30, I had a shoe box full of medication that I was intending to take when I turned 30.

You’ve brought up a point called emotional therapy. In preparation for this conversation, I had a conversation with my therapist. People who read this show know that I worked with an organization called Headstrong. They work with veterans and transitioning veterans for the rest of their life. As long as they want to talk to somebody, they’re there.

I have somebody I’ve been working with for several years. It’s life-changing for me as I’ve struggled through my transition journey. I was telling him about this episode and sitting down with you. He brought up the concept of emotional therapy. He said exactly what you said, which was it used to be people would go into therapy and they would say, “Tell me what’s going on?”

What has evolved in therapy over the years is, “Tell me how you feel.” Some people struggle to express how they feel and put it into words. The next step of that is to say, “Where do you feel it? Where in your body do you feel something? Is it in the chest, heart or head?” Through identification of where you feel certain things, for lack of a better term, then you can start to work on the driving factors that put you there. I thought that was an interesting point and topic that was brought up that you referenced here, especially in terms of how you feel when you do hold someone’s hand.

I think about holding my mother and my father’s hand. I had a father for 30 years longer than I had a mother. It’s a long time. He was my only parent for 30 years. I would still hold his hand even as I grew up because I liked holding his hand and I loved him.

There are some keywords that you’ve identified with each one of the sections of this book. I would like to throw them out here and ask you why you chose these. For the childhood section, you use safety guidance, connection, direction, kindness, necessity, fun and calming. Why those in relation to childhood?

They all refer to reasons why one would hold a child’s hand to keep them safe because they’re vulnerable creatures. You see all the time, kids learning how to cross the street on their own and look left and right. The parents are like, “Do I not have them go? Do I hold their hand or not hold their hand?” You’ll see parents and kids walking along, swinging their hands, which is the fun part or two parents picking up the kid on either side while they’re holding hands. Each of those represents a reason why you would hold hands with the child.

I find the whole book fascinating. You pick it up, look at it and say, “It’s a book of people holding hands of pictures,” but it’s so much deeper if you’ll take the time to embrace what you’re looking at. I came across those sections with those keywords. When you go back and look at the pictures again, keeping those words in your mind, it’s like it comes to life.

That’s the intention.

The second part of the book is Holding Hands Is Love, in which you’ve quantified love as adulthood. How come? Why do you call it adulthood love?

When you think about it, it’s hard to figure out what to call that section. It’s not just adults because it starts fairly young. We figured 1820. Couples can mean anything but it didn’t always feel right. There are a couple of threesomes, like three people holding hands in the book, not many but there are a few of them. I didn’t just want to call it couples. Let me just call it love because that’s when people discover adult love, usually, at some point on some level in their lives.

For you, adulthood brought leaving Canada, coming to the US, initially going into the finance industry and then transitioning to film, can you talk about that journey? You call it Getting Out Of Canada.

[bctt tweet=”You don’t want to take people out of the experience of having feelings about looking at photos.” username=”talentwargroup”]

It was one of those rare cases where my father had a green card after my mom died. We came in under his green card because we were under 21 at the time. I didn’t expect to be coming to the states but that’s what happened. In graduate school. When I was interviewing for jobs, they offered me a job in the states because they said I could work there. I took it and that’s how I got here in the first place.

I have dual citizenship, which you’re allowed to have. It’s been interesting but I also am aware. I have a lot of friends all over the place and a lot of them have friends from college in the town. I don’t have any friends from college anywhere in the country because I didn’t go to college here. None of them came down here. That’s a little bit different but it’s been a great experience to be here.

Americans are out there with everything as we know. It made it easier to take pictures. I didn’t find as many pictures of people holding hands in Canada, for example, as they do here. Granted, I live in New York and there are people everywhere. I must have taken eight pictures of people without trying. I couldn’t resist because sometimes I’m like, “I’m not going to take that. I have to run too fast to catch up with them.” These were great.

You have a lot of pictures too from California. That was cool looking at the book, trying to figure out where they were taken and then identifying, “I know exactly where that is.”

Good for you because I thought about it. People say, “Why on each picture do you say where it was?” I said, “I don’t want to take people out of the experience of having feelings about looking at the photos.” That’s why there aren’t that many quotes. I had twice as many to start with and just pulled them all out.

There was a lot on Santa Monica and Venice beach.

That’s where they hold hands.

You started working in finance and then come to a realization it was not for you. I’ll tell a story. When I got out of the Army and went to business school, I worked at Merrill Lynch. That was a defining moment for me to start to figure out who I wanted to be and what I wanted to do in life. You went into the film. How come?

There’s something to me that’s unique about the film business because each film is a product on its own and tells a story. No two are the same and they’re not cookie-cutters. You’ll see that there are 2 or 3 films on the same subject because every so often, there are disaster movies that happen in the 1st period of about 5 years. It was like the volcano movie, earthquake movie, the fire and the high rise movie and then something else happens. Each story is different. I love reading and books. Many of the movies that are out there come from some other source of book, a short story or a play. I didn’t want to be doing numbers where it didn’t matter, whether it was me or somebody else who was doing the transaction, which is the case in a lot of finance.

You met your husband on the set of Patriot Games, Harrison Ford. I love Harrison Ford. He’s awesome. You also dedicated the book to Mace where you said, “Who taught me how to see.” What does that mean?

My wonderful, late great husband Mace was a photographer as a very young person and that was his passion. He took photos and had a great eye his whole life. He came second in the Pulitzer as a teenager during World War II. The story is that the picture that won was the flag being put up on Iwo Jima. They later discovered that that was posed but they let it win anyway because of patriotism, war and everything else.

His photo was one photo. Meaning in those days, you had to have negative, develop and print the photos. He had a room on his camera for one more photo. He was walking along the street in Brooklyn. He saw a cab approaching and heard somebody on the third floor yell out, “Sammy is home.” He didn’t know what it meant.

He grabbed his camera, the cab door opened and the father came running out of the printing shop. The mother comes tearing down the stairs with her apron and a guy gets out of the cab on crutches. The one shot he got is the father with his hand on the son, the mother hugging him, tears in the father’s eye, the printing company in the background and the soldier on his crutches. He taught me how to see that one shot.

“He taught me how to see that one shot.”

I still have trouble doing it because, in the end, it’s a natural talent. A lot of his heroes, David Douglas Duncan was one of them, the war photographer. He had a way of inserting you into the photo. That’s what Mace did. He looked at all my photos. He’s the one who said after about 80,000 photos, “What are you going to do with all these photos? Why do you keep taking them?” That’s when I thought, “I better do something.” That started the process that led to the book.

Was he hard on you?

No, but he would just say, “Good. Okay,” when he’d see the photos. I learned a lot about taking photos. I thought you were going to ask me about what makes a good photo.

Let’s ask that.

I discovered and if you saw my computer, you’d see that I think I’ve got a great photo. There’s a couple holding hands in a great way and it’s close up but somebody is walking a yard ahead of them or there’s somebody’s clothing, leg, bag or something in the frame. I discovered that if there’s nobody else around and it’s just an isolated couple holding hands, as you can see in the book, those are the best photos. It forces you to double focus. Not only the holding hands, the focus of the couple from the back but there’s nothing else in the shot to distract you.

As you went through this phase of your life, you talked about depression and spent 25 years trying to save your mother. As you built the relationship with your husband, how did you handle that? How did you come out of it?

It turned out that my husband’s mother suffered from severe depression and that was interesting to me. He struggled with depression his whole life. He was what we call high functioning, as I was considered because I could still go about my day. I never spent a day in bed. Neither did he. We always got up and had our day but in my case, there was a vice around my head sometimes for days on end. It helped him understand what happened to me when I had periods, especially in my 30s and 40s when I was severely depressed. It didn’t show. We’d still go out to dinner parties but I wished I would wake up dead. I’d fly and wish the plane would crash.

[bctt tweet=”Meditation can bring you from the ceiling up to the ground level.” username=”talentwargroup”]

It’s hard to explain but there’s a book by William Styron, which was very famous, called Darkness Visible. It is a short book about his experience with depression. The way he describes it is real. It’s the one book I’ve read more than once that puts you in the place of somebody who’s struggling with severe depression. There’s no easy answer. Except in my case, I feel like I’ve collected a toolkit of things to do to help me feel better. It turns out taking the photos is one of them.

What else is in the toolkit?

Daily meditation, no matter what meditation. When I first started, I put a timer on for three minutes and thought about my to-do list, everything else and what the day was like. “This was stupid. Why would I do this?” The timer went off and I said, “That didn’t work.” I didn’t try it again for ten years but I tried it again. There are a lot of free apps. One of the great free ones is UCLA Mindful. They’re free. They’re guided meditation starting with five minutes.

I have a lot of younger friends. I say to them, “Nobody on the planet can give me a good reason why they can’t spend five minutes a day meditating.” I will not give it up for anything. If I have to get up at 4:00 in the morning, which I did for a show, I’ll wake up in time to meditate first because it settles me for the day. Frankly, it brings me from the ceiling up to the ground level.

It doesn’t need to be woo-woo. I asked Sean Lake from BUBS Naturals about this in an earlier episode because he was very big on meditation and that’s a supplement brand. He was the first person who brought up meditation to me when I stopped. I said, “Tell me how you do it.” People put a stigma on something like meditation and say, “I have to be all weird and levitating.” It’s not at all.

It can just be quiet. You can turn a timer on for five minutes and breathe in and out. Try focusing on your breath for five minutes. It’s hard. For some people, yoga is meditation. For other people, exercise is meditation. Almost anything can be a meditation. I love the concept of labyrinths where you one foot slowly or even heel-toe walk around it, forcing yourself to focus on that.

The words you attributed to this love phase were vulnerable, support, hopeful, grounding, transformational, centering, energizing and sexy. Why those?

They’re my experience. I feel that all of those came with being in a relationship. In this case, I’m referring to my relationship, which turned into a marriage. I thought, “I’m a human. Everybody else is human.” I’m guessing that these will apply to other people as well. It seemed like they did. They were all fairly specific and also able to be general.

I thought that they were very easy to identify with. We talked about chapters and you go through these different chapters in your life. As an adult, which is the majority of your life, is spent in this middle phase. You could almost write a chapter somewhere within that phase of your life around each one of those. The final section of the book is called Holding Hands is Togetherness. Five years ago, you fell on a sidewalk in California and suffered a blackout concussion. Can you talk about what happened?

One of the other daily tools that I use is exercise. I walk 4 or 5 miles every other day no matter what. I was doing my walk, minding my own business. I had crossed Sunset Boulevard and took a step on the sidewalk. The next thing I knew I remember being in a blackout, which was weird. I heard a scream. I woke up and realized I was lying on the sidewalk. I was screaming. Some people ran over to help me and said, “You fell.” I said, “What happened?” They helped me stand up. They said, “Your face is bleeding.” I said, “I’m fine.” I was 200 feet from the dentist’s office where I was headed. I said, “I’m going to the dentist.”

They said, “You should go have an ambulance.” “I don’t need an ambulance. I just need to go to the dentist and get my tooth fixed.” I show up at the dentist and they said, “What happened?” “I fell on the sidewalk. I’m fine.” They brought me ice and Advil for my face, which was bleeding. She did my dental work. I called my internist and said, “I don’t want to go to the hospital. I’m fine.” He made me an appointment with a plastic surgeon. I went and had 28 stitches down the side of my face.

The dentist worked on you when you had it all up.

It’s not arteries and stuff. It was closed, iced and it wasn’t bleeding. He took all the glass out of there because my sunglasses had smashed into my face and all the black glass from the sunglasses was in the wound anyway. The headaches didn’t happen until a week later. I had a headache for a year and a half straight somewhere in my head, either in the front, the back or migraine, which I’d had before but never like this. It was like it was here along with I was dizzy. I couldn’t focus, fill out a form or read. I was in the middle of Moby Dick and I had to put it aside.

I had all these things going on. I had MRIs and scans. Every male doctor said, “You’re fine. There’s no bleeding or cracks. Everything is fine.” It’s like, “It’s not fine. I can’t drive a car. I’m anxious. I can’t sleep. I’m afraid of having a blackout. I’m dizzy all the time. I can’t read a book or focus.” I had to beg for vestibular therapy. That’s going on one hand. I’m functioning, sleeping, getting up and cooking. I’m having my day and working on my photos.

The one thing I could do was look at the photos on the computer. For the first three weeks, I limited my computer time. After that, I started looking at the photos. Even in that horrendous state, because it turned out I had post-concussion syndrome for two years, I felt better when I looked at the photos of people holding hands. It made an iota of difference. At that point, I still wasn’t sure what I was doing with them. If that can help me in this state, can it help other people? What always something that I think about is, “Can I be of service? How can I be of service?” This book is part of my way of trying to be of service and pass on the good feelings.

“Even in that state, I felt better when I looked at the photos of people holding hands.”

In an earlier episode, we interviewed Richard Hanbury, the Founder of a company called Sana Health and the Sana device. He has told a similar story. When he was nineteen years old, he was in Yemen driving his vehicle across a bridge. There’s a truck oncoming and he has to make a decision, hit the truck or drive off the bridge? He chooses to drive off the bridge.

He lives but he’s paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of his life. As he’s lying in the hospital bed, he has tremendous nerve damage. He’s in this amount of pain where the doctors tell him, “Based on the amount of pain that you’re in and the level of narcotics that we have to give you, we’re giving you five years to live.” Their assessment was that he would come to the pain or take his own life due to it.

He is lying in the bed, watching the movie Hudson Hawk. You’re going to appreciate this being in a film with Bruce Willis. He finishes the movie and realizes things about this last little bit that there have been periods of this movie that activated his brain in a way that he felt no pain. He’s not a scientist or a doctor but he starts to think, “No one is going to save my life for me. I have to do it myself.”

Is there a correlation to the visual stimulus in these sections of this movie that could train neural pathways in somebody to take the pain away? He has dedicated and devoted the rest of his life to the development of the Sana device, which has received conditional FDA approval. He’s won all innovation awards. He’s worked with Richard Branson and people who’ve done their world flights where he’s helping them sleep better because these devices are being developed to retrain the neural pathways to interpret pain. Your story reminds me of that because it is those stimuli that can almost take those sensations away. It’s fast.

It takes us out of ourselves for a minute. It sounds like that’s what happened when he was watching the movie. I read something like 90% of our thoughts are about ourselves, self-talk and 80% of them are negative. If you can get out of your head for a bit, it’s a good thing.

[bctt tweet=”90% of our thoughts are about ourselves, and 80% of them are negative.” username=”talentwargroup”]

Unless you are super arrogant.

It’s always about you.

You struggled during this time.

I remember saying to my husband, “I want to die.” While I was at it, I decided to come off the depression meds I was on because I figured they weren’t helping me anyway. I felt so miserable. I said to him on more than one occasion, “If I die, remember to tell whoever’s doing the whatever that I was coming off depression meds,” which is another whole episode of what it’s like to try and come off depression meds. Many people don’t bother because it’s horrible and you’ll feel horrible. It’s a different kind of withdrawal.

It was a terrible time. I still went out. We’re out a lot. We had a very social life. He was in the film business. I showed up anyway but it was pure hell. What ended up helping me on a physical level was an alternate doctor who was trained as an internist but he was a healer in Brooklyn, and also music therapy, which I flew to Toronto to get based on a book I read. I was willing to try almost anything to feel better. A lot of it became part of my toolkit.

The alternate therapies are I find so fascinating. Coming out of the military, you talk a lot about post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. There’s this concept of Operator Syndrome, which Dr. Chris Frueh talks about. I wear WHOOP to track my functionality, my sleep patterns and how does that equate to my rest verse work cycles. Too many times, we rely on narcotics. The joke always in the military is like, “Drink water and take two aspirin. You’ll be fine.” That ramps up as you come in and start talking about, “I have these other ailments.”

For years, I was on anti-inflammatories for a back injury. When I came off of them, I couldn’t walk because there was a pain in my shins. That took two months to go away because that had been being masked by these other drugs. With the alternative therapies, we’re at a point in innovation in medical but then also in mental health where we can’t be afraid to introduce these things. It’s something as simple as this book and how you’ve quantified this ability to give it a try and see what happens, maybe it works.

I have some friends who are psychotherapists and two of them have said they could give this book to their clients and have them look at it for a week and come back. They would have months of things to talk about from looking at the images.

The words associated with this last section are healthy, compassion, healing, human, companionship, inspiring, spiritual and relaxing. I’m going to ask you to describe their importance but very importantly, you said, “As we were about to leave the world, we reach out instinctively for a final moment of comfort.” Your husband passed away at 93 years old, which is a feat well done in itself. Why in our final moments do we come full circle? At birth, we’re born, given to our mother and immediately create that connection. In death, that circle is completed.

It is completed and instinctual if there’s another human around. Many people will talk about sitting by the bedside of somebody who is in their last weeks, months or moments. Almost inevitably, they’re touching them somewhere, the hand, the leg, the foot, whatever might be comfortable for the patient. It’s this desire to connect. As far as I know, nobody who’s about to pass on knows where they’re going. There may be an issue of fear also about, “Where am I going? What’s going to happen?” Towards the end, Mace kept saying, “I want to know what’s next. I want to know what’s next,” which I thought was amazing.

The book has gained tremendous traction in the mental health arena. You’re donating a portion of all the proceeds to the book to The Hope for Depression Research Foundation. You’re involved in several medical research studies that are including MRIs and CT scans. Can you talk about what’s next for you? What’s next for getting the book out there? Why are these medical conversations with these research institutes is important?

There are two things. One, The Hope For Depression Research Foundation has been around for many years. They do a lot of work and outreach working to fight depression and mood disorders. This book was given away to everybody at their luncheon in November 2021. This ties in with the scientists I spoke to most, Dr. Coan, down at the University of Virginia, who studies Holding Hands. He gives a class called Holding Hands, which is bizarre.

When you think about it, it’s like, “Who would have thought there’s a class in holding hands?” It turns out there’s very little literature. If you look up books on holding hands, you won’t find any other than this one. There’s very little literature other than the obvious that it lowers blood pressure and increases oxytocin. It’s good for the brain and soul. There’s not much written about it.

This scientist at UVA has been doing MRIs of people who are holding hands with somebody outside the MRI. They give a small shock to the person in the MRI and see what happens to their brain when they’re holding hands with somebody and when they’re not. They notice that if they’re holding hands with somebody, the pain doesn’t register nearly the same way as when they’re by themselves. We’ve been in touch and I sent him a copy of the book.

I said, “Have you ever researched what happens when looking at images of people holding hands?” I’m going to suppose that looking at images of people holding hands is going to change somebody’s brain even infinitesimally because it certainly does to mine. I have some friends who’ve written me and said they keep the book beside their bed and look at it at night so they can feel better before they go to sleep. I’m going to be working with him. I’m going down there to speak. I’m excited to talk about it some more.

I have a test question for you. Do you believe people when they say they don’t need anybody else?

No.

The whole conversation has been about connection and relationships. As you’ve told your story, it is based on connection, community and building relationships. I agree with you.

Even the Dalai Lama doesn’t stay alone all the time. He’s out there in the world connecting to people and maybe he’s comfortable for days or weeks. Many people go and be in silence for a long time but it doesn’t mean they don’t need people. I don’t know that many people, other than the odd Hermit you hear about up in the Hills for 20 or 30 years. Statistically, everybody is always in connection with somebody somewhere. As I was told years ago, you don’t ever need more than a handful of friends but we all need somebody. There are a lot of songs written about that. It’s good for the brain and health to be in connection with people.

As we close out, the Jedburgh had to do three things every day as their core foundational tasks, habits and toolbox but they had to be able to shoot, move and communicate. If they did these three things as the foundations every day, then they could apply their focus to more complex challenges that came their way. What are the three things that you do every day to set the foundations for success in your world?

We’ve already talked about two of them. I meditate every morning, no matter what, which calms my brain down and gets me in a good place to start the day. I exercise every day, either something like Pilates, some yoga or walking. I connect with somebody every day. There’s never been a day that went by that I can think of that I didn’t speak to at least one person. I try and make three phone calls a day to people, texts a day to people I care about or email.

I’m in touch with my siblings. Those same five of us are incredibly close. We Zoom all the time. I’m building a house on one of my sister’s properties and the others who want it will be coming and visiting. That connection is incredibly important to me. I find that no matter what’s going on in my life, if I have people to share it with, whether it’s friends, family or people particularly close to me, it makes a difference, as in calming everything down in a good way.

Meditate no matter what, exercise and connect with someone every day.

Those are my Jedburghs.

One of the foundations of the show is the concept of the nine characteristics of performance that special operation forces use to recruit, assess, select and develop talent. We weave a lot of them into different conversations. I didn’t explicitly reference many of them here in this conversation because the words you’ve used to describe the different chapters of our lives are powerful. I want to make sure that we’re going to highlight those as we put this episode out and tie it back into these different periods of life of why is holding hands important and what we seek from someone in our different periods of life when we hold hands.

I bring this up here because, at the end of our episodes, I do think about these nine characteristics, drive, resiliency, adaptability, humility, integrity, curiosity, team ability, effective intelligence and emotional strength. You’ve certainly exhibited all of these in our conversation here. When I think about you and your story, integrity comes to my mind. Integrity is defined as our ability to do what’s right. When you think about connection, relationship building and community building, you can’t have meaningful, lasting connections if they’re not grounded in integrity and doing what’s right when no one’s looking. It is the second piece of that.

What you’ve put together in this book and presented to the world in terms of how holding hands affects our health, our mental, physical and emotional being is grounded in being true, honest and displaying integrity to ourselves and those around us. I sincerely appreciate the time that you’ve spent here with us, sharing your book and talking about the different phases and chapters of your life. I look forward to getting this message out, watching this book continue to grow and the effect that it’s going to have on everybody out there. Thank you.

I appreciate it. It was great to be here and a real pleasure to meet you and speak to you. Thank you. All the best to you.